Please enjoy Cory Doctorow’s short story “Shannon’s Law,” featured in the anthology Welcome to Bordertown, out May 24th from Random House. For an introduction to the world of Bordertown, click here.

***

When the Way to Bordertown closed, I was only four years old, and I was more interested in peeling the skin off my Tickle Me Elmo to expose the robot lurking inside his furry pelt than I was in networking or even plumbing the unknowable mysteries of Elfland. But a lot can change in thirteen years.

When the Way opened again, the day I turned seventeen, I didn’t hesitate. I packed everything I could carry—every scratched phone, every half-assembled laptop, every stick of memory, and every Game Boy I could fit in a duffel bag. I hit the bank with my passport and my ATM card and demanded that they turn over my savings to me, without calling my parents or any other ridiculous delay. They didn’t like it, but “It’s my money, now hand it over” is like a spell for bending bankers to your will.

Land rushes. Know about ’em? There’s some piece of land that was off-limits, and the government announces that it’s going to open it up—all you need to do is rush over to it when the cannon goes off, and whatever you can stake out is yours. Used to be that land rushes came along any time the United States decided to break a promise to some Indians and take away their land, and a hundred thousand white men would wait at the starting line to stampede into the “empty lands” and take it over. But more recently, the land rushes have been virtual: The Internet opens up, and whoever gets there first gets to grab all the good stuff. The land rushers in the early days of the Net had the dumbest ideas: online pet food, virtual-reality helmets, Internet-enabled candy delivery services. But they got some major money while the rush was on, before Joe Investor figured out how to tell a good idea from a redonkulous one.

I was too young for the Internet land rush. But when the Way to the Border opened again, I knew there was another rush about to start. I wasn’t the only one, but I will tell you what: I was the best. By the time I was seventeen, there wasn’t anyone who was better at getting networks built out of junk, hope, ingenuity, and graft than Shannon Klod. And I am Shannon Klod, the founder of BINGO, the lad who brought networking to B-town.

I’ll let you in on a secret, something you will never find out by reading the official sales literature of the Bordertown Inter-Networkers Governance Organization: It was never about wiring up B-town. It was never about helping the restaurants take orders from Dragon’s Tooth Hill by email. It was never about giving the traders a way to keep the supply chains running back to the World. It was never about improving the efficiency of Bordertown’s bureaucracy.

The reason I rushed to Bordertown—the reason I pulled every meter of copper and attached every spellbox, heliograph, and carrier pigeon to a routing center, the reason I initiated a thousand gutterpunks and wharf rats into the mysteries of TCP/IP—had nothing to do with becoming B-town’s first Internet tycoon. I don’t want money except as a means to getting my true desire. You may not believe this, but I gave away nearly every cent I brought in, literally threw it into the street when no one was looking.

The reason I came to B-town and set up BINGO and all that glorious infrastructure was this: I wanted to route a packet between the World and the Realm. I wanted to puncture the veil that hangs between the human and elfin domains with a single piece of information, to disorder the placid surface of the membrane that keeps these two worlds apart.

I wanted to bring order and reason and rationality to the Border. And gods be damned, I think I succeeded.

***

You may have heard that the Net was designed to withstand a nuclear war. It’s not true, but it’s truthy, in the neighborhood of true. You may have heard that the Internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around. This also isn’t true, but it’s also truthy enough to quote.

The fact is, the Net is decentralized and fault-tolerant. That means anyone can hook up to it, and when parts of it break down, the rest keeps going. In this regard, it is one of the most stupendous creations our stupid species can lay claim to, right up there with anything our long-lived cousins from the other side of reality can cite. They’ve got their epic magicks and their enchanted swords and their fey lands where a single frozen moment of deepest sorrow and sweetest joy hangs in a perpetual balance that you could contemplate for a thousand lifetimes without getting the whole of it.

But gods be damned, we invented a machine that allows anyone, anywhere, to say anything, in any way, to anyone, anywhere.

“Shannon! Shannon! Shannon!” They chanted it from the base of the spiral stairs that led up to my loft, my motley crew of network engineers, cable pullers, technicians, and troubleshooters. More reliable than any alarm clock, my army knew that I could not be roused until the world had arranged itself into a state of sufficient interestingness. “Shannon!” they chanted, and the smell of coffee wafted up through the hatchway whence cameth the stairwell’s top. They had my espresso machine down there, and it had a head of steam. The regular thunk-tamp-hiss-thump of Tikigod pulling shots of lethal black caffeine juice was a fine rhythm section for the vocals.

The universe had attained liftoff. It was time to meet my public.

Back in the World, I’d had a ratty and much-loved bathrobe I’d made my mom buy me after I read the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy books. I’d brought the bathrobe with me to B-town, but I got rid of it after I found my loft and realized that the regal effect of descending a wrought-iron black spiral staircase before your marshaled troops faded if they could look up at your dangling junk while you made your way. I’d had a seamstress on Water Street run me up a set of checked flannel pajamas instead and got myself a pair of matching carpet slippers. All it wanted was a pipe and a basset hound and I’d have been the picture of middle-class respectability.

“Good morning, all and sundry,” I said, clenching my hands over my head like a prizefighter, celebrating my victory over sleep, another round lost by Morpheus, that candy-ass lightweight. “Let there be coffee!”

The secret of my success? Coffee. Black Cat Mama was B-town’s most reliable coffee supplier, thanks to superior communications technology: She used my networks to coordinate with a variety of suppliers in the World and hadn’t run out of inventory since we put her online. She’d been trapped in B-town during the great Pinching Off and didn’t really grok networks, but she grokked coffee. She paid me in espresso roast beans, and we ground them ourselves—rather, Tikigod’s legion of love slaves ground them for her, hand-cranking the burr grinders to a fine powder that ranged from 200 to 250 microns, depending on the humidity, the beans, and the vagaries of the crema, as determined by Tikigod each morning.

Bottom line: If you worked for BINGO, you had coffee, all day long, enough to set every hair on your body on end, enough to make the tip of your nose go numb, enough to make you clamp your jaws and tap your teeth together just to hear the bony click in your skull.

The secret of my success? Work for BINGO and no matter how hard you danced the night before, no matter what you poured down your throat or smoked or ate, you would be a thrumming bowstring for your workday. Oh, yes.

They cheered me, and Tikigod’s love slaves ground the beans, and the boiler hissed as its spellbox sang a high and tight note, and the black waters flowed, and the milk frothed, and the network began its day.

***

You know what pisses me off? The whole business: the Border, B-town, the Realm, all of it. Here we have this amazing thing, this other universe sitting there, only one hairbreadth from the universe we’ve been untangling for centuries, and what do we use it for? Fashion. Music. Bohemia. Some trade, some moneymaking.

Nothing wrong with any of it. But am I the only gods-be-damned human being who wants to sit down with whatever passes for a scientist in Elfland and say, “We call this gravity. It decreases at the square of distance and makes its effects felt at the speed of light. Tell me what you call it and how it works for you, will you?”

We say that magic and technology are erratic in the Border, but that’s just a fancy way of saying we don’t know how they work here. That we haven’t applied systematic study to it. We have regressed to cavemen, listening to shamans who tell us that the world can’t be known. Screw that. I’m going to unscrew the universe.

But first someone’s got to get the heliographers to stop pranking the carrier-pigeon handlers.

The Net’s secret weapon is that it doesn’t care what kind of medium it runs over. It wants to send a packet from A to B, and if parts of the route travel by pigeon, flashing mirrors, or scraps of paper cranked over an alleyway on a clothesline, that’s okay with the Net. All that stuff is slower than firing a laser down a piece of fiber-optic, but it gets the job done.

At BINGO, we do all of the above, whatever it takes to drop a node in where a customer will pay for it. Our tendrils wend their way out into the Borderlands. At the extreme edge, I’ve got a manticore trapper on contract to peer into the eyepiece of a fey telescope every evening for an hour. He’s the relay for a kitchen witch near Gryphon Park whose privy has some magick entanglement with the hill where he sits. When we can’t get traffic over Danceland in Soho because the spellboxes that run the amps and the beer fridges are fritzing out our routers, our kitchen witch begins to make mystic passes over her toilet, which show up as purple splotches through the trapper’s eyepiece. He transcribes these—round splotches are zeroes, triangular splotches are ones—in 8-bit bytes, calculates their checksum manually, and sends it back to the witch by means of a spelled lanthorn that he operates with a telegraph key affixed to it with the braided hair of a halfie virgin (Tikigod’s little sister, to be precise). The kitchen witch confirms the checksum, and then he sends it to another relay near the Promenade, where a wharf rat who has been paid handsomely to lay off the river water for the night counts the number of times a tame cricket sings and hits a key on a peecee in time with it. The peecee pops those packets back into the Net, where they are swirled and minced and diced and routed and transformed into coffee, purchase orders, dirty texts, desperate pleas from parents to runaways to come home, desperate pleas from runaways to their parents to send money, and a million Facebook status updates.

Mostly, this stuff runs. On average. I mean, in particular, it’s always falling apart for some reason or another. Watch me knock some heads and you’ll get the picture.

The heliographer’s tower is high atop The Dancing Ferret. Everyone told me that if Farrel Din could be persuaded to get involved with BINGO, all of Soho would follow, so I did some homework, spread some money around, and then I showed up one day with a wheelbarrow filled with clothbound books that I’d had run up by the kids who put out Stick Wizard.

The fat elf came out of the stockroom with a barrel of dandelion wine and a thoughtful look. “What the hell is that?”

“It’s Wikipedia, Mr. Din. Let me explain.” And that was the start of a beautiful friendship. I’d printed and bound every Wikipedia entry as of the day the Border reopened (I’d put a copy on a memory stick on my way out the door), as well as the discuss link for every page. It filled two hundred volumes, each as big as a phone book, and Din installed a special set of spelled bookcases for it on a wall of the bar, fronted with glass that would only swing open twice for every drink you bought. It created an entirely new trade for his establishment, a day crowd that turned up to drink small beer and pore over the collected and ridiculous wisdom of the World.

The Dancing Ferret’s door stood open to catch the spring breeze when I got there, sometime before lunch. One of Farrel Din’s flunkies had set out sofas around the bookcase, and they were crowded with elves and halfies and even humans. I figured the humans were people who’d lived through the Pinching Off in B-town, trying to figure out WTF had happened to the World in the blink of an eye.

Din came out of the back room looking just as he had the day I’d met him, three years before. Elves age much slower than us, and our little mayfly lives must zip past them like a video stuck on 32X fast-forward. He shook his head at me and pulled a face. “They’re at it again, huh?” He rolled his eyes at the ceiling, indicating the tower on the roof and the mischievous heliographers.

I nodded. “Kids will be kids.” Yes, I was only a couple years older than them, but I wasn’t a kid; I was a respectable businessman. Someone had to be the grown-up at BINGO. “I’ll get ’em into line.” I nodded at the crowd poring over the books. “Looks like you’re doing pretty good there,” I said. There were even a couple of suits from up the Hill, proper businessmen and straight cits who you wouldn’t ever think to find in Soho, let alone slumming it at The Dancing Ferret. But knowledge is power and knowledge is money, and I’d given Farrel Din a very concentrated lump of knowledge.

He made another face. “Bah.” He actually said “Bah,” like someone in a fairy tale. Gods-be-damned elves. What a bunch of drama queens. “Used to be you could have a real, proper, no-fooling, bona fide pointless bar argument around here: a fight over someone’s batting average or how many moons Jupiter has or what the Eight Wonders of the World are. Now”—he shook a fist at the bookcases and the customers who sat before them— “someone just goes and looks up the answer. Where’s the romance in that? I ask you. Where’s the chance to use rhetoric, force of personality, style, and wit to prove a point in a world where any tight-assed fool can have an answer, a fact, in a second?”

I tried to figure out if he was pulling my leg. It was nearly impossible to tell. Elves.

“Okay, well, you just let me know if you want me to take them out again.” I’d heard that there were three more print shops working on their own Wikipedias, brought from the World on thumb drives and laptops, more up-to-date than what Farrel Din’s fifty-odd linear feet of shelving supported. I welcomed the competition: Once there was a thriving market for Wikipedias in B-town, I’d unveil my secret weapon—a BitTorrent client I’d rigged up right on one of our fastest nodes, downloading a daily tarball of the latest Wikipedia edits. In other words: let them try to compete with me, but I would always have the most up-to-date version.

Farrel Din grinned suddenly, without any mirth, his fat face somehow wolfish. “Not on a bet, sonny. Those things have sucked up so much—” He used an elfin word that I didn’t recognize, though it sounded like the word for “curiosity,” like they shared a common root. “I figure they’ll be ripe in a few years, and then . . .” He got a faraway look in his eyes. I shook my head. Elves. In a few years, I’d have punctured the Border; I’d have plumbed the unplumbable; I’d have—

“Okay, whatever you say, Mr. Din. I gotta go bang some skulls now.”

He waved absently at me as I ascended the narrow ladder that led to The Dancing Ferret’s roof. The rungs had some minor spell on them that was supposed to make them grippy and safe, but the magic didn’t work as advertised (surprise, surprise). Some of the grips were so sticky it felt like they’d been covered in honey, others felt like splintery wood, and one right up at the top felt like it had been coated in Vaseline. Gods be damned. I’d have to come back here with a roll of skateboard tape and take care of it the old-fashioned, brute-force World way.

Up on the roof, I planted my hands on my hips and squinted at the tower top high above me, where the heliograph’s disk winked. Holding the angry-dad pose, I waited for my wayward children to glance down at me, feeling slightly foolish but committed to ensuring that they knew there was about to be hells to pay for their shenanigans.

Nothing. Indeed, as I watched, someone swung the heliograph’s glittering mirror around suddenly, tilting it downward, and raucous laughter emanated from the tower top. I imagined I could hear the outraged squawk of a distant pigeon as it was blinded by the burst of light, sent veering off course along with its payload of precious data.

Bugger this. I put my tongue behind my teeth and my hand in my pocket and mimed a whistle as I touched the spelled-carved cricket I keep in my jeans. Everyone respects someone who can whistle so loud it’s like a physical blast, a “missile whistle,” but the truth is, I can’t manage anything more than a squeak. It’s the carved cricket, made from a piece of knotty fig from Australia and tweaked by an Elfmage so that it fires off a positively violent sound, like the blast from a referee’s whistle, and if I do the mime at the same time, you’d never know it wasn’t me.

Two heads poked over the parapet of the semaphore tower. One was shaved and one sported a huge spray of pink hair whose split ends were visible from the ground. There was one missing. I made with the whistle again, emphatically tracing out the rune over the cricket’s back. A third head poked out, with deliberate slowness, this one topped with a mop of green dreads that hung down like long snakes.

“Ladies, gentleman,” I said, cupping my hand to my mouth. “If I might have a quiet word?”

I fancied that I could see their guilty expressions despite the distance, all but Jetfuel, my bright and reckless little protégé with the dreads, a natural leader who, it seemed, couldn’t help but make trouble wherever she went.

They continued to stare at me. “Down here,” I said. “Now.”

Gruntzooki and Gruntzilla (Baldy and Pink Hair) came down the ladder, keeping three points of contact at all times. But Jetfuel stood up, hiked up her greasy, torn jeans, and stepped off the platform, snagging the bug-out pole with one hand just before gravity snatched her out of the sky and dashed out her pretty brains. She coiled her powerful legs around the pole, squeezing it with her thighs to slow her descent so that she touched down at the same time as her colleagues.

They lined up like the naughty children they were, so comical that I had to struggle to keep my face serious. “Who’s winning?” I asked.

They shifted uncomfortably.

“Come on. Who’s in the lead?”

Gruntzilla and Gruntzooki pointedly didn’t look at Jetfuel. I leaned toward her, noticing that she’d added some new piercings since I’d last seen her—two studs in her left cheek that she’d threaded with a genuine, old-school punk-rock safety pin. I had to admit, it looked good.

“Oh, Jetfuel?” I said sweetly. I could tell she was trying not to laugh. It was an infectious laugh. A pandemic laugh. “How many points ahead are you?”

“Three hundred and seventeen,” she said, and the laugh was in her voice. Jetfuel is a halfie with a supernatural gift for juggling routing tables in her head, and I’ve never figured out if she had some kind of glamour that made her so impossible to get properly angry with, or whether it’s just that she’s beautiful, smart and good at her job, and doesn’t give a damn about anything.

“How many points per pigeon?”

“Fifteen.”

I’m good at math. “You’ve zapped twenty and one fraction of a pigeon?”

“I got two extra points for knocking a Silver Suit off his bike.”

Oy vey. “So, besides hardworking avians and the duly-appointed officers of the law, is there anyone else you’ve been zapping with that highly polished, highly critical, and highly expensive mirror up there?”

She pursed her lips, making a show of thinking. “I got a dragon once,” she said. “That time a big old bastard came down from the Border along the Mad River? I got it right in the eyes. But no one else saw, so it didn’t count.”

I whispered a charm that was supposed to keep away the evil eye (“hinky-dinky-polly-voo, out, out, bad spirits, this means you”). “You’re joking.”

She pursed her lips again, shook her head. “Nuh-uh. It looked like it had found true love for a second, then turned and flapped away. Guess you could say I saved B-town from being incinerated by a giant, fire-breathing mythological beast, huh? Sure wish I’d had a witness. Dragons should be good for like a thousand points.”

It’s a glamour that keeps you from getting angry with her. It must be. I was trying so hard, but I wanted to grin. “Jetfuel,” I said, “we’ve talked about this. You are a truly kick-ass heliograph operator, and I think you’re a very nice person and all, but if you zap one more pigeon—”

“You’ll turn her into a goon?” Gruntzooki snorted and Gruntzilla hid her mouth with her hand.

“I’ll turn you into an unemployed person,” I said. “With no coffee.” I nodded at the thermos clipped to her belt with a carabiner that had been imported from the World at great expense. “When was the last time you bought even a featherweight of beans? How long do you imagine you could function once you had to pay street price for your jet fuel, Jetfuel?”

I could see that one hit home. She slumped a little.

“Shannon,” she said. “It’s just that it’s so lame. We don’t need the pigeons. They crap everywhere. They have crazy latency. Cats eat them.” I recognized her tone, and it warmed my heart: the sound of a techie who was offended at the existence of an inelegant solution to a challenging problem.

I nodded at Gruntzilla and Gruntzooki, then tipped my head toward the unoccupied tower. They took the hint and clambered up the ladder, and a second later, their mirror was winking furiously at the other towers we’d put up all over B-town. All over town, dozens of router managers made note of the fact that The Dancing Ferret station was up and routing again.

“Over here,” I said, walking to the edge of the roof and sitting with my legs dangling over the street below. Jetfuel sat down beside me, unscrewed her thermos, and titrated some caffeine into her bloodstream. I fished some black licorice gum out of my shirt pocket and popped it into my gob. We all have our vices. “You remember when I got here? You remember what I wanted to do?”

She’d been the first one who’d believed in my ideas, and she’d brought a dozen of my first recruits into the shop, trained them herself, climbed buildings in jingling harness to set up repeaters.

She screwed up her face into an improbably pretty look of disbelief. “You mean the Elfnet?” We’d called it that as a joke, but it stuck.

I nodded.

“Oy,” she said. She’d gotten that from me. “Really? Now?”

“Why not now?” I asked.

She flapped her arms over Bordertown, arrayed before us. “Because,” she said, “it’s all working now. You’ve got one hundred percent coverage; you’re signing up customers as fast as you can punch down nodes and kludge together peecees to stick on them. Shannon, you’re rich. You’re practically respectable. They write about you in the good newspapers now, not just the free sheets.”

“Why are you zapping pigeons, Jetfuel?”

“What has that got to do with anything?”

“Answer the question. Honestly. What did those poor birdies ever do to you?”

She shrugged and looked down at her dangling feet. “I guess . . .” She shrugged again. “I dunno. Bored? That’s it, just bored.”

I nodded. “Once it’s good, once it all runs tickety-boo, the challenge goes out of it, doesn’t it?”

She looked at me, really looked at me, with the intensity I remembered last seeing through the lenses of a pair of binocs as we stared at each other across a mile of freespace, trying to get our first two mirrors lined up exactly right. Most of my people saw BINGO as a maintenance problem, keeping the whole hairball running. But Jetfuel was in it from the start. She saw the mission as building stuff.

“Oy,” she said.

“Oy,” I said.

She finished her coffee and screwed the lid back on, then stood up and dusted off her hands on the seat of her torn jeans. “All right,” she said, holding out a hand to me. “Let’s go storm Elfland.”

***

No human can enter the Realm. No information about the Realm can pierce the Border, except in the mind or scrolls of an actual elf, and from what I understand, the information changes somehow when they pass through the Border. Like the information has an extra dimension that can’t fit into our poor, stupid 3-D world.

There’s a book called Flatland, about all these two-dimensional beings who can only move from side to side and are visited by a 3-D person. It’s a good book, if a little weird. But the thing is, it is possible for the 3-D and 2-D people to talk to each other; they just need to work it all out.

That’s why I think I can do it. The Internet is designed to be fault-tolerant and transport-independent. I can route a packet by carrier pigeon, by spell, by donkey, or by runic script written on vellum and tucked into a diplomatic pouch behind the saddle of a highborn courier. My architecture doesn’t care if the return volley arrives late; it doesn’t care if it returns out of sequence. That’s fault-tolerant. That’s transport-independent.

The first-ever Internet connection wasn’t much to write home about: A computer at UCLA and a computer at Stanford were painstakingly wired together, and a scientist at UCLA began to log in to the remote end. He typed “L-O,” and then the computer crashed. From those first two bytes, the network was gradually, inexorably improved upon, until it was the global system that we know and love today. That’s all I need: a toehold, a crack I can jam a lever into and pry, until the gap is as wide as the whole world. Just let me round-trip one packet over the Border and I’ll do the rest. I know I can.

Jetfuel and I walked down to the river, headed for BINGO headquarters. Our heads nodded together in solemn congress, as they’d done countless times before, when BINGO was just a dumb idea.

“Have you found a remote end?” Her voice had an odd quality, a weird and almost angry sound that I hadn’t ever heard in it before.

“No,” I said. “Not yet. But there are so many Highborn on the Net these days, I thought I’d just look around at our best customers and see if anyone’s name jumps out as a good candidate.”

“It’s going to be a delicate operation,” she said. “What if you ask someone to help you and he rats you out instead?”

I shook my head. “I’m not sure there’s anyone to rat me out to. It’s not like there’s a law against piercing the Border, right? I mean, there’s like a natural law, like the law of gravity. But you don’t go to jail for violating gravity, right?”

She snorted. “No, usually you go to the hospital for trying to violate gravity. But, Shannon, that’s the thing, you don’t understand them. They don’t have laws like you think of them. There isn’t a Trueblood Criminal Code Section Ten, Article Three, Clause Four that says ‘Humans and human communications apparatuses are prohibited from engaging in real-time congress across the Border that separates our realities.’ The laws of the Realm are more like”—she waved her long, slim fingers, all chipped glitter nail polish and anodized hot-pink death’s head rings—”they’re like paintings.”

“Paintings.”

She twisted her face up. “Okay, ever see a painting and go, ‘Whoa, that’s some painting’?”

I nodded.

“You ever wonder why? Why it grabs you by the hair and won’t let go? Why it compels you?”

I shook my head. “I don’t really look at a lot of paintings.”

She snorted again. “Shannon, you’ve lived in Bordertown for three years. You are surrounded by paintings and sculpture and kinetic art and dance and music. How is it possible that you haven’t been looking at paintings?”

“I look at JPEGs,” I said.

“All right. JPEGs work, too. Ever wonder why sometimes you’ll see something, something made up, something that never happened—maybe something that looks like nothing in the real world at all—and you’ll want to look some more? Why a line of music that doesn’t sound like any words your mind can turn into meaning still stops you in your boots and makes you want to listen?”

“Sorta. I guess.”

“Shannon Klod, I absolutely refuse to believe that you don’t have any aesthetic sense. You don’t live in a cardboard box. You don’t sleep on plain sheets. You don’t cut your hair with children’s scissors when it gets in your eyes and forget about it the rest of the time. You’d rather eat good food than bad food. You can pose all you want as a robotic techie who has no time for all this artsy-fartsy crap, but it doesn’t wash with me.”

This is the thing about Jetfuel: She’s had my number since the first time we talked, her demanding to see one of the peecees I’d brought from the World after the Pinching Off. I knew better than to argue when she got like this. “Fine,” I said. “Fine, fine. I am as dainty an artiste as any you’ll find starving in a Mock Avenue garret. My life revolves around plumbing the unplumbable and reveling in its mystery. There are shades of green and blue that move me to tears. What’s your point?”

“This is the point: Art moves you in some way. It fits and feels right, or it doesn’t fit in a way that feels deliciously wrong. You can talk all you want about brushstrokes or shades of green and blue, but none of those are the things that move you, right? It’s something else: something you might call spiritual. Art is art because it makes you feel artful. And that’s the basis for the Realm’s legal system.”

I shook my head. We were getting close to the BINGO office, where once again I’d have to be Responsible Grown-up Shannon Klod, but for now, I was really enjoying this moment with Jetfuel, recapturing an excitement I hadn’t felt since the first two nodes went live. “I don’t understand,” I said. It felt good to admit this—Shannon Klod usually had to have all the answers.

“Human laws and rules are based on, what, mutual understanding. Someone says, ‘I propose a law that makes it illegal to take a dump over here where we all get our water, because that way we won’t all die of poo-poisoning.’ The wisdom of that law is obvious, so, after some debate, we make it a law. But in the Realm, they make laws because the laws make the world a more interesting place—interesting in the way that a painting or a dance or a song can arrest your interest. So you might say, ‘I propose that people who take a dump here should be made to perform a penance by making a willow stop weeping.’ And just like most people understand why poo and the water supply don’t go together and can agree on the human rule, Highborn respond to their rules by their aesthetic sense and agree to the ones that are most beautiful or the most ugly—the ones that make the best art.”

“You’re serious?”

“As a heart attack. So there’s not a law against running a network drop into the lands beyond the Border the way that you think of laws existing. But it’s still forbidden, and the penalties are real.”

“Like what?” I said, thinking of all the money BINGO was bringing in, more than I knew what to do with. “What kind of fines are we talking about?”

“Oh, not fines,” she said. “Those, too, I’m sure. But smuggling carries serious penalties: your heart shrunk to the size of a marble and placed on a cairn in the Grove of Despair for a hundred winters, all the songs snatched from your throat for a time not to exceed the reign of the Blood Queen Under the Sea, that sort of thing.”

I stopped and searched her face. “Tell me you’re joking.”

She shrugged. “Shannon, you’ve been dreaming about this for years, but you’ve never asked me what I know about the Realm. Perhaps it’s time you started.”

I almost said, Of course I didn’t ask you—you’re a B-town halfie! But I knew that would be the wrong thing to say. “How did you find out all this stuff?” I said, trying for delicacy.

“You mean, how did a B-town halfie find out all this stuff, right?” Anger moved across her face, then departed. She smiled her don’t-give-a-damn smile and said, “My big sister came to visit.”

“I didn’t know you had a sister,” I said. I hadn’t ever met Jetfuel’s family, though she’d pointed out their house once as we stood on a rooftop with a cable spool and a witch who dusted it with blessings and wards as it unspooled yard after yard of insulated category-five enhanced wire.

“Half sister,” she said. “From my dad’s first wife.” And I understood. Her father was an elf, a proper one, from what I gathered: highborn and high-blooded with the titles and fancy underpants that went with them. So his first wife, whoever she was, was probably another elf, from before he fell in love with a human woman, and that meant that Jetfuel’s big sister was—

“Your sister’s an elf?”

She nodded and rolled her eyes. “Like, seven feet tall, legs up to here, waist you could wrap one hand around, wrists like twigs, eyes like a cat’s, hair as fine as spun gold. The whole package.” We were standing across the road from BINGO now, neither of us wanting to go inside and break the spell that had come over us, the old excitement. “She came through a year ago. She was ever so excited about this networking stuff. Wanted to see it for herself. Dad’s glad to have her but doesn’t want her hanging out with me in case I corrupt her ever-so-pure highbornedness. So of course she sneaks out to see me every chance she gets.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. “She sounds perfect,” I said. “Why didn’t you tell me about her?”

She looked shifty. “I wasn’t sure you were still interested, you know. You’ve been so busy with all this Big Business stuff—”

I could have kissed her. Well, not really. In fact, specifically, I was not under any circumstances going to kiss her. That would be so inappropriate. “Jetfuel, I am most assuredly still interested. I would like to meet your sister at the first possible opportunity. What’s her name, anyway?”

“Don’t laugh,” she said. “Okay? Promise?”

“Cross my wires and hope to fry,” I said.

“She calls herself Synack. She’s in love with the seven-layer OSI network model.”

I held my hand over my heart and faked a swoon. “Oh my bars and starters. You think she’ll do it, even if it’s risky?”

She nodded, her green dreads flying around her face, wafting a little of the warm-bread smell of her scalp that I’d always tried so hard not to notice. “In a second.”

“Get her,” I said.

“Zero perspiration,” she said, and struck off for BINGO. “She’ll be online. She’s always online.”

***

Here’s what I wanted to do: I wanted to send a message to Faerie. Not a whole packet, but at least something machine-generated that traversed the Border, arrived in its recipient’s hands, and then confirmed its receipt to me.

Here’s how I planned to do it. I’d have a computer generate a hundred random digits:

110011110100110110110010111011000100101100110111 11101101111011110110100010110010001111010100000

10010

and divide them into four lines of twenty-five:

1100111101001101101100101

1101100010010110011011111

1011011110111101101000101

1001000111101010000010010

and then add another digit to each row and column so that each one had an even number of 0s and 1s:

1100111101001101101100101 1

1101100010010110011011111 1

1011011110111101101000101 0

1001000111101010000010010 0

0011000110001100011101101

This last digit was the “error-correcting code”—it meant that if any of the digits in my rectangle of numbers got flipped, you could tell, because you wouldn’t have the right number of 0s and 1s anymore. If the number checked out, the recipient would know for sure that it hadn’t gotten foobarred in transit.

Then the recipient would generate a ten-digit random number and multiply my number by it and make another rectangle of 0s and 1s for me. She’d transmit that back to me with the same encoding. I’d verify the message, then divide the new number by the first one I’d sent, which would leave me with the random number. I’d encode that the same way and transmit it back—now we’d both know that we could faithfully transmit numbers to each other.

Once I’d made that tiny little bit of headway, I could build on it, piece by piece, until I was sending entire Internet packets back and forth across the Border. Do that a couple billion times, and you can send someone a copy of Wikipedia. For now, though, all I wanted to do was get a single number there and back again. If information can emerge from the Realm, then we can reconcile its physics with our physics. We can begin to turn its mysteries into facts and truths. We can start to heal the world, make it one place again.

I don’t care if my packet is carried on the backs of butterflies or spelled into the sky by a wizard. I don’t care if the checksums are computed by an Elfmage on a scroll of living parchment or added up by a peecee with a spellbox. I don’t even care if an elf princess who smells just like fresh-baked croissants has the packet shipped to her with her cloaks and paint boxes and returns it hidden in the margins of a portrait of her beloved father.

Which is exactly what Synack is proposing to do. Jetfuel neglected to mention the croissant smell, but apart from that, she had every detail right. Synack looked like the elf princesses who’d spent two hundred fifty years stalking the runways of every major fashion show for the years that the Border was closed off from the World, cinematically perfect, cat-eyed and pointy-eared, with cheekbones you could use to grade a driveway. And she dressed pure Realm, in shimmery fabrics that draped like they meant it, lots of layers and watery prints. When she breezed through BINGO’s reception area, every conversation fell silent and every eye turned to her. She looked at us through cool silver eyes, raised a graceful hand, and said, “Hey, dude, is this where you keep all the Internets?”

Jetfuel snorted and slugged her in the shoulder. Side by side, you could see the family resemblance, though Jetfuel was like something a talented comix maker might do with a box of crayons, while her sister looked like something painted by a Dragon’s Tooth Hill artiste with fine brushes and watery inks.

I coughed to cover my spacey moment and said, “Yes, indeed, this is where we keep the Internets. Can someone get the elf lady a bucket of Internets, please? You want a large bucket or a small one?”

Synack smiled and let her sister guide her back to the meeting room, which was where we brought our best corporate customers, so it had a minimum of obscene graffiti, and most of that was covered over with network maps and pricing schedules. Jetfuel excused herself to get us all coffees—she’d had two while we waited and had quizzed Tikigod intensely over the grind she was using that day and the crema it generated—leaving me alone with Synack.

“How long since you left the Realm?” I said.

Synack looked up, as if counting hash marks on the inside of her eyelids. “About a year. Jetfuel and I had been writing back and forth, and she sent me the Wikipedia entry on Caer Ceile, which is our family’s estate. It was so weirdly wrong in such an amazing way that I knew I had to come to the World and see it for myself. I’ve been begging my father to let me apply for a visa to leave the Borderlands and go to one of the easy countries, like Lichtenstein or Congo, but he’s worried I’ll get cut up and left in a Dumpster or something. So I can’t get onto anything near low-enough latency to edit Wikipedia in real time.”

“You should try the guest terminal here,” I said. “Most days around two p.m., there’s a thirty-minute window where we get down to about ten microseconds to our next hop, a satellite uplink in North Carolina. We’ll pull something like five K a second then. If you hit Wikipedia with a text-only browser, you should be able to get at least one edit in.”

Her eyes crossed with delight, and it was so cute that I wanted to put a pat of butter on her nose to see if it would melt. “Could I?”

I shrugged, trying for casual (as casual as I could get with this radiant elf princess wafting her croissant smell at me). I was rescued by Jetfuel, who had three handmade cups filled with three handmade cappuccinos, each dusted with a grating of my private reserve of 98 percent cacao chocolate, stuff that was worth more, gram for gram, than gold. I kept it under my mattress. She met my eye and smiled.

Jetfuel sipped her coffee, licked the foam off her lips, and turned to her sister. “Here’s the deal. We’re going to put a number in your luggage, and it will follow you back to Caer Ceile. It’ll be short—less than one K. We’ll put it in your paint box, engraved on one of your brushes. When it arrives, you generate the acknowledgment—use something good for the randomizer, like a set of yarrow stalks—and paint it into the border of a landscape of the fountains. Send it to Dad, a present from his wandering daughter. I’ll copy it off, generate the confirmation, and, well, get it back to you. . . .” She trailed off. “How do we get it back to her?”

I shrugged. “It sounded like you had it all planned out.”

“Two-thirds planned. I mean, I guess she could put it in a letter or something.”

I nodded. “Sure. We could do the whole thing by mail, if necessary.”

Synack shook her head, her straight ash-blond hair brushing her slim shoulders as she did. “No. It’d never get past the contraband checks.”

“They read all the mail that crosses the Border?”

She shook her head again. More croissant smell. It was making me hungry, and uncomfortable. “No . . . it’s not like that. The Border . . .” She looked away, searching for the right words.

“It’s not really directly translatable in Worldside terms,” Jetfuel said. “There’s a thing that the Border does, on the True Realm side, that makes it impossible for certain kinds of contraband to fit through. Literally—it’s the shape of the Border; it is too narrow in a dimension that we don’t have a word for.”

I must have looked like I was going to argue. Jetfuel crossed her eyes, looking for a moment just like her sister. “This is the part I could never get you to understand, Shannon. Once you cross from the Realm over the Border, you enter a world where space isn’t the same shape. Your brain is squashed to fit the new shape, and it can no longer even properly conceive of the idea that the Realm operates on.”

I licked my lips. This was the kind of thing I lived for, and Jetfuel knew it. “So it sounds like you’re saying that it’ll be impossible to do this. Why are you helping me?”

“Oh, I think it’s totally possible. As to why I’m helping you”—she gestured at herself, flapping her hands to indicate her decidedly halfie appearance—”it’s pretty much inconceivable that the Lords of the Realm would ever deign to let a mule like myself through their gate, though it’s technically possible. I am never going to get across the Border. I am never going to be able to directly experience that state, the physical and mental condition of being in the True Lands. This is the closest I can come.” She looked so hungry, so vulnerable, and I saw for just an instant the pain she must live with all the time, and my heart nearly broke for her.

Her sister saw the look, too, and she squirmed, and I wondered what it must be like to be the sister who wasn’t an object of shame. Poor Jetfuel.

I dragged the conversation back to technical matters. “So why will the paintbrushes pass? Or the painting?”

Synack said, “Well, the brushes are beautiful. And the painting will be beautiful, too. Plus, it’s poetic, the juxtaposition of the data and the art. It changes their shape. Beauty camouflages contraband at the Border. Ugliness, too.”

I felt my heart thudding in my chest. It must have been the coffee. “That’s the stupidest technical explanation I’ve ever heard. And I’ve heard a few.”

“It’s not a technical explanation,” Synack said.

“It’s a magical one,” Jetfuel said. “That’s the part I keep trying to explain to you. Here in B-town, we get used to thinking of magic as something like electricity, a set of principles you can apply through engineering. It can work like that—you can buy a spellbox that’ll power a bike or a router or an espresso machine. But that’s just a polite fiction. We treat spellboxes like batteries, take them to wizards for recharging, run them down. But did you know that a ‘dead’ spellbox will sometimes work if you try to use it for something tragic, or heroic? Not always, but sometimes, and always in a way that makes for an epic tale afterward.”

“You’re telling me that there’s an entire advanced civilization that, instead of machines, uses devices that work only when they’re aesthetically pleasing or dramatically satisfying? Jesus, Jetfuel, you sound like some poet kid fresh out of the World. Magic is just physics—you know that.” I could hear pleading in my own voice. I hated this idea.

She heard it, too. I could tell. She covered my hands with one of hers and gave a squeeze. “Look, maybe it is physics. I think you’re right—it is physics. But it’s physics that depends on the situation in another dimension that brains that have been squished to fit into the World can’t think about properly.”

Synack nodded solemnly. “That’s why the Highborn don’t trust Truebloods who were raised here. They’ve spent their whole lives thinking with squished brains.”

Jetfuel took it up again. “And that’s why what we’re doing here is so important! If we can connect both planes of existence, then we can transmit events happening here to the Realm to be viewed with the benefit of its physics! Anyone in the World can use the Realm as a kind of neural prosthetic for seeing and interpreting events!”

I started to say something angry, then pulled up short. “That’s cool,” I said. Both sisters grinned, looking so alike that I had to remind myself which was which. “I mean, that is cool. That’s even cooler than—” I stopped. I didn’t really talk much about my idea of using information to lever open the barrier between the worlds. “That is just wicked cool.”

“So how do we get the confirmation back?” Synack said.

Jetfuel finished her coffee. “We start by drinking a lot more of this,” she said.

***

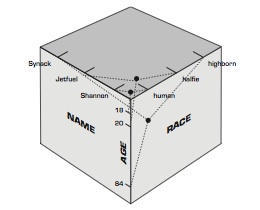

More dimensions are easy. Say you’ve got a table of names and ages:

ShannonJetfuelSynack

201884

If you were initializing this as a table in a computer program, you could write it like this: (shannon,20)(jetfuel,18)(synack,84). We call that a two-dimensional array. If you wanted to add race to the picture, making it a three-dimensional array, it’d look like this: (shannon,20,human)(jetfuel,18,halfie)(synack,84,highborn). If you were drawing that up as a table, it’d look like a cube with two values on each edge, like this:

That’s easy for humans. We live in 3-D, so it’s easy to think in it. Now, imagine that you want the computer to consider some-thing else, like smell: (shannon,20,human,coffee)(jetfuel,18,halfie,bread)(synack,84,highborn,croissants). Now you have a four-dimensional array—that is, a table where each entry has four associated pieces of information.

This is easy for computers. They don’t even slow down. Every database you’ve interacted with juggles arrays that are vastly more complex than this, running up to hundreds of dimensions—height, fingerprints, handedness, date of birth, and so on. But it’s hard to draw this kind of array in a way that a 3-D eye can transmit to a 3-D brain. Go Google “tesseract” to see what a 4-D cube looks like, but you’re not going to find many 5-D cube pictures. Five dimensions, six dimensions, ten dimensions, a hundred dimensions . . . They’re easy to blithely knock up in a computer array but practically impossible to visualize using your poor 3-D brain.

But that’s not what Jetfuel and Synack mean by “dimension,” as far as I can tell. Or maybe it is. Maybe there’s a shape that stories have when you look at them in more than three dimensions, a shape that’s obviously right or wrong, the way that a cube is a cube and if it has a short side or a side that’s slanted, you can just look at it and say, “That’s not a cube.” Maybe the right kind of dramatic necessity makes an obvious straight line between two points.

If that’s right, we’ll find it. We’ll use it as a way to optimize our transmissions. Maybe a TCP transmission that’s carrying something beautiful and heroic or ugly and tragic will travel faster and more reliably. Maybe there’s a router that can be designed that will sort outbound traffic by its poetic quotient and route it accordingly.

Maybe Jetfuel is right and we’ll be able to send ideas to Faerie so that brains with the right shape will be able to see their romantic forms and dramatic topologies and write reports on them and send them back to us. It could be full employment for bored elf princes and princesses, shape-judging, like an Indian call center, paid by the piece to evaluate beauty and grace.

I don’t know what I’m going to do with my network link to Faerie. But here’s the thing: I think it would be beautiful, and ugly, and terrible, and romantic, and heroic. Maybe that means it will work.

***

The calligrapher was Highborn. Jetfuel assured me that nothing less would do. “If you’re going to engrave a number on a paint-brush handle, you can’t just etch it in nine-point Courier. It has to be beautiful. Mandala is the unquestioned mistress of calligraphy.”

I didn’t spend a lot of time up on Dragon’s Tooth Hill, though we had plenty of customers there. The Highborn don’t like Border-born elves, they have very little patience for halfies, they really don’t like humans, and they really, really don’t like humans who came to B-town after the Pinching Off passed. We weren’t poetic enough, we newcomers who’d grown up in a world that had seen wonder, seen it vanish, seen it reappear. We were graspers at wealth, mere businesspeople.

So I had halfies and elves and such who did the business on the Hill.

The calligrapher was exactly the kind of Highborn I didn’t go to the Hill to see. She was dressed as if she had been clothed by a weeping willow and a gang of silkworms. She was so ethereal that she was practically transparent. At first she didn’t look directly at me, ushering us into her mansion, whose walls had all been knocked out, making the place into a single huge room—I did a double take and realized that the floors had been removed, too, giving the room a ceiling that was three stories tall. I kept seeing wisps of mist or smoke out of the corners of my eyes, but when I looked at them straight on, they vanished. Her tools were arranged neatly on a table that appeared to be floating in midair but that, on closer inspection, turned out to be hung from the high ceiling by long pieces of industrial monofilament. Once I realized this, I also realized that the whole thing was a sham, something to impress the yokels before she handed them the bill.

She seemed to sense my cynicism, for she arched her brows at me as though noticing me for the first time (and thoroughly disapproving of me) and pointed a single finger at me. “Do you care about beauty?” she said, without any preamble. Ah, that famed elfin conversational grace.

“Sure,” I said. “Why not.” Even I could hear that I sounded like a brat. Jetfuel glared at me. I made a conscious effort to be less offensive and tried to project awe at the majesty of it all.

She seemed to let that go. Jetfuel produced her sister’s paint box and set the brushes down, click-click-click, on the work surface, amid the fine etching knives, the oil pastels, and the pots of ink. She also unfolded a sheet of paper bearing our message, carefully transcribed from a peecee screen that morning and triple-checked against the original stored on a USB stick in my pocket. She had refused to allow me to print it on one of the semi-disposable inkjets that littered the BINGO offices, insisting the calligrapher wouldn’t deign to handle an original that had been machine produced.

The calligrapher looked down at the brushes and the sheet for a long, long time. Then I noticed that she had her eyes closed, either in contemplation or because she was asleep. I caught Jetfuel’s attention and rolled my eyes. Jetfuel furrowed her brows at me, sending me a shut-up-and-don’t-make-trouble look that was hilarious, coming from her. Since when was Jetfuel the grown-up in our friendship? I went back to studying my shoes.

“I don’t think so. I think you wouldn’t recognize beauty if it poked you in the eye. I think you care about money and nothing but money, like all humans. Silver-mad, you are.”

I had to rewind a bit to figure out that she was replying to something I’d said ten minutes before. She’d opened her eyes and was staring at me, finger out, little half-moon of nail aimed directly at me like she was about to spell me into oblivion.

I was angry for half a second; then I chuckled. “Lady, you’ve got the wrong guy. There’s plenty of things wrong with me, but my love of money isn’t one of them.” Besides, I didn’t add, you clearly didn’t get this swanky mansion by caring only for beauty. “And since you’re not doing this job for free, let’s just both admit that neither of us are adverse to a little cash now and then.” I thought I saw a hint of a smile cross her face; then she scowled at the paper again.

“This is what I am to engrave upon these brushes?”

We both nodded.

She looked longer at it. “What is it?”

I looked at Jetfuel and she looked at me. “A random number,” I said.

She ran her finger along it. “Not so random,” she said. “See how the ones appear again and again?”

“Yeah,” I said. “They sure do. That’s how random numbers work. Sometimes you get ones that seem to have patterns, but it’s like the faces you see in the clouds—just illusions of order from the chaos.”

“No wonder you in the World are so poor in spirit, if you think that it’s impossible to scry from the clouds. That’s powerful magic, sky magic.”

The last thing I wanted was an argument. “Well, let me put it this way. We chose this number at random. If it’s got a message from the gods or something in it, we didn’t put it there, we don’t care about it, and we don’t know about it. Can you engrave it?”

The calligrapher folded her hands. “I will dance with these numbers,” she said. “And perhaps they will dance with me. Come again tomorrow and I will show you what we have found in our dance.”

I waited until the door clicked shut behind us before I hissed, “Pretentious, much?” and rolled my eyes. Jetfuel snorted and socked me in the thigh, giving me an instant—but friendly—deadleg.

“She’s the best,” Jetfuel said. “If anyone can turn a hundred-twenty-eight-bit number into art, it’s her. So don’t piss her off and maybe she’ll ‘dance’ our number across the Border.”

***

Jetfuel was the first person to really get what I was doing with BINGO and B-town. Oh, there were plenty of geeks who thought it was all cool and nerdy and fun, and plenty of suits from the Hill who wanted to invest in the business and cash out with a big fat dividend. But Jetfuel was the only one who ever understood the beauty of it all.

Somewhere along the years, she became a mere heliographer and I became a mere businessman, and until that fateful day on the roof, we barely spoke to each other.

Tomorrow, it will all change. Tomorrow, we will begin to make beauty—instead of money—again.

We sat in my bedroom, listening to the techs moving around below us, shouting and typing on peecees and squabbling and sucking down coffees. I had my chocolate stash out, and I’d set it down between us on the windowsill where we sat, looking out at the Mad River and its meandering course all the way into Faerie. As I reached for the chunk of black, fragrant, slightly oily chocolate, our hands brushed and I felt something race up my arm to my spinal cord and up into my brain, like a ping that passes between two routers. I could tell she felt it, too, because she jerked her hand away as fast as I had.

We were saved from embarrassment by the arrival of Synack, looking even more elfy-welfy than usual, her hair topped with a coronet made from silver leaves, her feet clad in sandals whose straps climbed up her long legs like vines. As we turned to her, I had a jolt of something entirely different—a feeling of nonrecognition, a feeling that this wasn’t the same kind of being that I was. This was a person whose brain sometimes pulsed and thought in dimensions I couldn’t grasp. This being was the product of a different set of physical laws than the ones my universe obeyed, physical laws that made exceptions for beauty and terror. Suddenly, Synack was as alien as a lobster, and her long legs and shimmering hair were as attractive as a distant star or the craters of the moon.

“I leave in an hour,” she said, out of breath from the climb up the stairs and the excitement of her impending departure. Her words broke the spell, and she was a person again, someone I could relate to and care about.

Jetfuel sprang from the windowsill and threw herself around her sister’s neck, tumbling her to my unmade bed. “I’ll miss ya, sis!” she said over the racket of small electrical components bouncing off the bed and side tables and rolling to the floor. The two of them giggled like any sisters, and I shook off the feeling of unreality and tried to recapture my excitement.

I stood up and wiped my hands on my jeans. The two of them stopped laughing and looked at me solemnly, two pairs of eyes, one silver and one brown, staring with complex looks that I couldn’t quite understand. “You’ve got your brushes?”

Synack nodded. “And I’ve been telling Father all about the painting I’ve been planning to make for him for days now, and he can’t wait to see it.”

We all looked at each other. “And you’ll come back once you get the reply transmission, right?” This was the hardest part, figuring out how to confirm with her that her message had arrived safely back at BINGO. The plan for this stank: Jetfuel was going to reduce her sister’s return volley to a hash—that is, a shorter number arrived at by running the long number through a prearranged function. The new number should be only ten digits long, which means that the odds against her guessing the correct value by random chance were 1:1,000,000,000. Pretty rare. Ten digits were easier to sneak over the Border than a couple hundred. Jetfuel swore that she could work them into a poem about the painting that she could mail back to her sister and that this would be beautiful enough to traverse the Border.

I hated this part. How the hell could I tell if it was a reasonable plan or totally nuts? I couldn’t see into this dimension where beauty could be measured and agreed upon. Neither could Jetfuel or Synack, but at least their brains were theoretically capable of it, on the other side of the Border.

“I’ll come back. With Father here in the World, I’m the mistress of Caer Ceile. That makes me gentry, properly speaking, with all the rights and entitlements, et cetera. Father will be furious, of course—he’s so glad that his precious daughter is getting out of mean old Bordertown.” She fell silent and carefully avoided looking at Jetfuel. The question hung unspoken in the air: If Synack is the precious daughter who’s too good for B-town, what is Jetfuel?

We all waited in the awkward silence. Then Synack said in a voice that was practically a whisper, “He does love you, you know.”

Jetfuel put on a big, fake smile. “Yeah, yeah. Every father loves all his children equally, even the half-breeds.”

“He left the True Lands for a human.”

Jetfuel’s smile vanished like a popped soap bubble. “It’s a vacation. A half century in the World, and then he can go back to the Realm.” She spread her hands out, miming unlike me.

“Um . . . ,” I said. “Not that it’s any of my business, but this is totally not any of my business.” They had the good grace to look slightly embarrassed.

“Sorry,” Synack said. “You’re right.” Somewhere in the distance, one of B-town’s many big clocks chimed four. “Is that Big Bend?” she said.

“Sounds like Old Tongue to me,” I said. B-town’s clocks kept their own time, but if you knew which clock was bonging, you could usually approximate the real time. Whatever real time was.

“I’d better get going.”

Jetfuel gave Synack another hug that seemed within three microns of being sincere. “Take care of yourself. Come back soon.”

Then Synack gave me a hug, and it was like hugging a bundle of sticks. That smelled like croissants. “Thanks for this, Shannon,” she said.

“Thank you!” I said, unable to keep the surprise out of my voice. “You’re the one taking all the risks!”

“You’re the one trusting me to take them,” she said.

Then she turned and left, going down the wrought-iron staircase like a . . . well, like an elfin princess picking her way delicately down a spiral staircase.

***

We didn’t get drunk. Instead, we went out onto the roof, climbing along the window ledge to where there was a convenient overhang that we used to chin ourselves onto the top of the building, which bristled with antennae and dowsing rods and pigeon coops and a triple heliograph tower. Back in the day, we’d practically lived on the rooftops of B-town, amid the broken glass and the pigeon poop and the secret places where the city slumbered like an ancient desert even as the streets below thronged with life and revelry.

Back in those days, it had been too much work to descend to street level with all our gear and then haul it back up onto the next roof. Instead, we got in touch with our inner parkour, which is to say that we taught ourselves to just jump from one roof to the next. Actually, technically, Jetfuel taught herself to jump from roof to roof, and then stood on the far roof shouting things like “Jump already, you pussy!”

She looked at me and shook out her whole body, from her dreads to her toes, like a full-length shiver. It was a moment of pure grace, the sun high overhead making her skin glow, her motion as fluid as a dancer. She gave me a smile that was as wicked as wickedness and then one-two-three hoopla! She ran to the edge of the roof and leaped for the next roof, which was a good two feet lower than the BINGO building—but was also a good eight feet away. She landed and took the shock in her whole body, coiling like a spring, then using the momentum to pop straight up in the air, higher than I thought it would be possible to jump. She turned and waved at me. “Jump already, you big pussy!”

It took me three tries. I kept chickening out before I took the leap. Jumping off a roof is dumb, okay? Your body knows it. It doesn’t want to do this. You have to do a lot of convincing before it’ll let you take a leap of faith.

At least mine did.

Jumping off a roof is dumb, but I’ll tell you what: Nothing beats it for letting you know that you are, by the gods, alive. When my feet crunched down on the next rooftop, my body accordioning down as it remembered what to do when I was hurling it through the sky, I had a jolt of pure aliveness that was a lot like what coffee is supposed to feel like but never quite attains. It was not getting drunk. It was the opposite of getting drunk.

She gave me a golf clap and then smiled again and one-two-three hoopla! She was off to the next roof. And the next. And the next. And where she went, I followed, my chest heaving, my vision sharper than it had ever been, my hearing so acute I could actually hear individual air molecules as they hissed past my ears. People looked up as we leaped like mountain goats, and I felt like physics might have actually suspended itself for our benefit, like we had stumbled onto something so beautiful and heroic (or so dumb and awful) that the universe was rearranging itself for us, allowing us to leap through a dimension in which the distance between two points was governed by how wonderful the journey would be.

We must have covered nine or ten roofs this way before we finished up atop a notorious Wharf Rat nest, right by the river, with nowhere else to go. Most people wouldn’t go near the building, but we’d had a repeater on its roof for more than a year, and the rats knew that it was good to have friends at BINGO, so they didn’t touch it. And there was the repeater: a steel box with a solar cell and a spellbox bolted to it, the whole thing in turn bolted to the roof. Two antennae sprouted from it, phased arrays tuned to reach other nodes, off in the distance.

We panted and whooped and thumped each other on the back and laughed and eventually collapsed onto the roof. It was hot high noon now, and the streets below thronged with people going about their business, oblivious to the data and the people flying over their heads. I was sweating, and I took off my shirt and wiped off my hair and armpits with it, then stuck it through a belt loop. Jetfuel shook out her dreads, and drops of sweat flew off her chin. She sat down abruptly. I sat down, too, and she pulled me to her. I leaned my sweaty head into her sweaty shoulder, and the distance between us telescoped down to microns, and time dilated so that every second took a thousand years, and I thought that perhaps I had found a way to perceive additional dimensions of space and time after all.

***

234404490694723436639143624284266549884089428122864 553563459840394138950899592569634717275272458858980 368990407775988619397520135868832869735939930461767 760810884529442067644734319876299352530451490411385 468636178784328214112884303704466427542100839502886 749241998928856357024586983052158559683995174900556 161227077835366410003843047289206505830702020787377 298368085308540469606276109017865079416024634017699 69569372007739676283842331567814474185

That’s the number that was worked into the twisting vines that twined around the frame of the painting of Caer Ceile that Synack sent back. I knew that it must be a beautiful painting, because it went through the Border. But I thought it was kind of flat and uninspiring. It looked like the pink castle at Disneyland, complete with the pennants and the shrubbery around it, and the mythical beasts that gamboled around its walls only completed the feeling that we were looking at something that came out of Fantasyland, not the Realm of Faerie. Maybe it was the composition. I don’t know much about painting, but I know that good paintings have good composition and that this one didn’t have something, so maybe it was the composition.

“That’s the family place, huh?” I said after I’d examined it. It hung in a dining room in which you could have fed fifty people. Jetfuel’s father’s dining room, which was paneled in somber woods that turned into seeking branches at waist height, living branches that grew straight up to the ceiling, supporting a network of leaves that absorbed the sound, giving the room the acoustic properties of a library or a forest glade.

A servant—a human servant, a middle-aged lady—padded into the room carrying a silver tray, which she set down on the long, lustrous table. The woman gave Jetfuel a warm hug and gave me a suspicious look before offering me a cup of tea. She fussed with small biscuits and cakes but didn’t bother us as we moved around the painting, which dominated one wall, using a spell-light to cast a bright spot on each leaf, each of us writing down each number in turn, checking each other’s work. My network operators did this all the time, but it had been years since I’d had to do it, and I’d lost track of how tedious it was. My people earned their pay.

We sat down to eat our biscuits just before her father’s keys rattled in the front door lock. Even before the knob had turned, Jetfuel’s back had stiffened, all the fun going out of her face. She set down her cookie and pursed her lips; then she stood and crossed to the doorway, looking down the hall as the front door swung wide. I trailed after her.

Her father looked like your basic Business District suit: conservative hair, a Worldly suit cut to emphasize his long, slender torso and limbs and neck. But for the silver eyes and pointed ears, he might have been a skinny banker on his way to Wall Street. He stepped into the cool dark of his hallway, already unbuttoning his jacket, and was just turning to hang it on a burnished brass coat hook when he caught sight of Jetfuel.

The war of emotions on his face was unmistakable: first delight, then sadness, then irritation. “Sweetheart,” he said. “What a nice surprise.” He made it sound real enough. Maybe it was.

Jetfuel jerked her thumb over her shoulder. “Dad, this is Shannon. I’ve told you about him. Shannon, this is Baron Fenrirr.”

He snorted. “You can call me Tom,” he said. He stuck out his hand. “Heard so much about you, Shannon. Good things! What you’ve done for our city—”

I shook his hand. It was cool and dry, and the fingers felt as long as patch cables. “Nice to meet you, too.”

And then we all stood, a triangle of awkwardness, until the baron said, “Right, well, plenty to do. Will you stay for dinner?”

I thought he must be asking Jetfuel, but he was looking at me. I looked at Jetfuel. She shook her head. “Plenty to do,” she said. “Got to get back to BINGO.”

That look of sadness again on his face, and then he nodded. He took one step toward the staircase that led to the upper rooms, where, I suppose, he kept his study. Then he turned again and shook my hand goodbye. “Nice to meet you. Don’t be a stranger.” After he let go, he turned and grabbed Jetfuel in a hug that was so sudden she didn’t have time to back away. She stiffened again, as she had at the table, but he kept squeezing, his face lowered to the top of her head, where it smelled, I knew, of bread. He kept on holding her, long beyond what a normal parental hug might have demanded. She slumped into his arms and then, tentatively, hugged him back.

“Okay,” she said. “Okay, enough.”

He let go and she slugged him in his skinny shoulder, and they smiled an identical smile at each other. He went upstairs. We grabbed our notebooks and our cookies, and Jetfuel called out a goodbye to the maid, and we stepped out into the day and started the walk to BINGO, where we would send back the third part of the protocol.

***

I thought Jetfuel’s poem was funny:

Five is a respectable digit,

But seven makes it look like a midget.

Nine puts them both to shame,

Weird old zero’s at both ends of the game.

Four’s quite square and not at all prime,

And you might say the same of our old friend the nine.

Two is prime and even as well,

Five is quite right to think that’s weird as hell.

Four’s for foreplay,

Which comes before six.

This poem’s full of numbers,

A rather good trick.

Jetfuel squinted at the sheet of paper and scowled at it and made ready to ball it up and toss it to the bedroom floor along with the previous fifty attempts. I stopped her hand, grabbing it in mine and bringing it up to my lips. “Stop already. Enough. It’s a funny poem. I think it’s beautiful. As beautiful as a financial report, anyway, and tons of those get across the Border.”

She shook her hand away from my lips and glared at me, then flopped against the pillows and nuzzled her head into my chest. “Financial reports aren’t contraband. This needs to be beautiful enough to pass on its own merits.”

I shook my head. “It’s beautiful. Enough. You’ve written a hundred poems. This one’s got everything—sex, midgets, and math jokes! That’s what I call beauty.”

“‘Six’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘trick.'”

“Sure it does. Six trick, six trick, six trick, six trick. Rhyme.”

She looked out the window at the twinkling Faerie dust streets of B-town. “I’ll take another crack at it in the morning,” she said.

“Put it in an envelope, affix postage, and give it to a runner downstairs to bring to the couriers on Ho Street.”

“You are the world’s worst boyfriend,” she said.

“And yet here we are,” I said, and kissed her.

***

How beautiful was the poem? I don’t know. Maybe it was beautiful enough to traverse the Border, and maybe Synack received it at Caer Ceile and stitched a beautiful embroidered frame for it and hung it on the wall, or maybe she burned it by moonlight or fed it to the unicorns or something.

Maybe Synack never received it and will spend the rest of her days as the mistress of Caer Ceile, attending Elf Parliament in gossamer dresses and tabling motions to increase the Faerie dust allotment to Narnia.

Maybe Synack received it and clutched it in her hand tightly and set off for the Border to hand it back to us, to prove that a single bit could traverse the invisible barrier that separates two worlds—two universes—but as she approached the Border from the Faerie side, she pricked her finger on a spinning wheel and fell into a thousand-year sleep. Or perhaps no time has passed for her as she crossed the Border, but the years have stretched by here.

In case you’re wondering, we still haven’t heard back from her.

Jetfuel’s dad installed a peecee in his study, and he sends Jetfuel email three times a day, which she almost never answers.

Some kid from the World just showed up with his own Wikipedia server that he’s running out of a Net café on Hell Street, and he’s maintaining the canonical B-town pages. Farrel Din is pissed.

I still think Jetfuel’s poem was beautiful. She gets up earlier than I do, and her pillow smells of warm bread, so I get to bury my face in it until the smell of the coffee and Tikigod’s shouting rouses me every morning.

Copyright © 2011 by Cor-DocCo, Ltd (UK)

From Welcome to Bordertown, edited by Holly Black and Ellen Kushner, with an introduction by Terri Windling, published by Random House, May 2011.

Bordertown and the Borderlands were created by Terri Windling, with creative input from Mark Alan Arnold and the authors of the previous stories and novels in the Borderland series (Borderland, Bordertown, Life on the Border, The Essential Bordertown, Elsewhere, Nevernever, and Finder): Bellamy Bach, Stephen R. Boyett, Steven Brust, Emma Bull, Kara Dalkey, Charles de Lint, Craig Shaw Gardner, Michael Korolenko, Elisabeth Kushner, Ellen Kushner, Patricia A. McKillip, Felicity Savage, Delia Sherman, Will Shetterly, Midori Snyder, Ellen Steiber, Caroline Stevermer, Donnárd Sturgis, and Micole Sudberg. The “Borderland” setting is used in this story by permission of Terri Windling, The Endicott Studio.