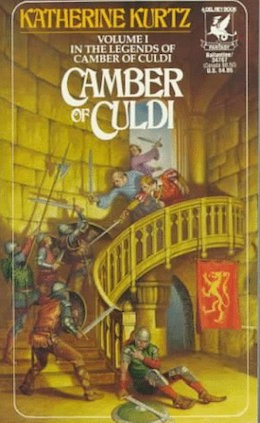

Welcome to the weekly reread of Camber of Culdi! We’ve traveled back in time from the days of King Kelson to the Deryni Interregnum. There’s an evil Deryni king on the throne, Camber has retired from royal service to spend more time with his family, and there’s a revolution brewing. And it looks as if Camber’s family will be right in the middle of it.

Camber of Culdi: Prologue and Chapters 1-3

Here’s What Happens: So here we are, according to the original edition, with “Volume IV in the Chronicles of the Deryni.” But the series is set centuries in the past of Volume I, and the world is rather a different place.

The Prologue is written in the vein of academic history, expanding (and expounding) on the theme of “Just who was Camber of Culdi?” It’s quite dry, with very long paragraphs and lots of names and dates, and most of it is not about Camber but about the anti-Deryni persecutions that erupted after the Deryni dynasty, the Festils, was overthrown. (Wencit, be it noted, is a Festil.) It’s massively spoilery, but then it’s presumed we already read the first published trilogy, so we know how it turned out.

I admit my eyes glazed over (and I was trained as an academic historian). I’d really rather just go straight into the story, please. Which begins when Camber was (is) fifty-seven years old, and the Festils have devolved into the Caligula-like King Imre, whom longtime royal servant Camber refuses to serve. There’s a tax revolt in the making, and nobody seems to be on the king’s side.

Chapter 1, mercifully, begins in proper Kurtzian narrative style, on a blustery late-September day in Tor Caerrorie. The first character we meet is Camber’s daughter Evaine, and she is doing the accounts. What she’s more concerned about, however, is something much less harmless, and she’s sending a message about it to her brother Cathan. Cathan is close friends with the difficult and mercurial king.

She’s also concerned about the reaction of her other brother Joram, who has a temper, and who is a Michaeline priest. She’s hoping that whatever it is will have resolved by Michaelmas, when Joram comes home for the holiday.

The narrative wanders off through a long and complex exposition of family history, which adds up, eventually, to the fact that her father Camber has retired to his academic studies after a lifetime of serving kings. Finally Evaine goes in search of her father, and finds him at the end of a contretemps with her cousin James Drummond.

Father and daughter discuss this briefly, then segue into the main issue. A Deryni has been murdered in the village, and the King has cracked down hard on the human population. They discuss the victim, Rannulf, and the morals and ethics of the murder and its consequences, which appears to have been perpetrated by a group called the Willimites. Rannulf was a reputed pedophile, and the murder looks like a revenge killing.

The discussion rambles from Rannulf to Joram the hotheaded Michaeline to the king’s problematical temperament to the manuscript Evaine has been translating.

Suddenly she’s distracted by a “curious golden stone,” which Camber informs her is a shiral crystal. It has peculiar properties. Camber demonstrates by going into a trance and causing the stone to glow. He has no idea what it’s for; he gives it to Evaine as a toy. Then they get to work translating obscure antique verse.

In Chapter 2, meanwhile, Rhys Thuryn is making his way through a crowded city to a place called Fullers’ Alley. He’s on his way to visit an old friend and patient (for Rhys is a healer), Daniel Draper. Dan is very old and (as Rhys reflects at length) isn’t long for this world.

He isn’t dead yet, however, and he’s still feisty enough to tell off the priest who is there to give him last rites, and tell off Rhys for good measure. He has something to tell Rhys, though it takes a considerable while for him to get around to it. He’s the lost heir of Haldane, and his real name is Aidan. Moreover, his grandson Cinhil is still alive, walled up in a monastery.

He’s telling Rhys, and trusting him, though Rhys is Deryni. He urges Rhys to Truth-Read him. Rhys eventually gives in, and sees that Dan really is who he says he is.

Then Dan puts him in a serious bind. Dan points out that the Festils have devolved into worse than tyrants. Cinhil is a possible alternative. He makes Rhys promise to consider the notion.

Dan carries a token, a silver coin minted in Cinhil’s abbey. The grandson’s name in religion is Benedict, but Dan dies before he can tell Rhys the man’s secular alias. The coin tells Rhys nothing he can make sense of.

This leaves Rhys with a terrible dilemma. He has no clue as how he’s going to handle it, but he has a definite sense that Dan’s end is in fact a beginning—of something.

As Chapter 3 begins, Rhys is soaking wet from riding all night in the rain to the Abbey of Saint Liam. There’s someone there who can possibly solve the riddle of Dan’s silver coin: his old schoolmate and dear friend, Joram MacRorie.

It takes him a while, with a trip down memory lane—he went to school here—and a rambling conversation with an elderly priest, who eventually tells him where to find Joram. He finds his friend in the library. (Joram looks and acts a great deal like a certain Duke of Coram a couple of centuries hence, though by rank and vocation he’s more like Duncan.)

Rhys hands him the coin, and we get a lengthy and loving description of our very sexy, very well-bred, very talented and politically astute young warrior priest, which segues into an even more lengthy explication of politics behind his father Camber’s very political retirement. (He left the royal service to spend more time with his studies and his family.) This goes over (and over)(and over some more) the earlier exposition about the situation, including his elder brother Cathan’s close friendship with the wicked and corrupt King Imre.

Finally, after several pages, the story wrenches itself back on track. Joram knows what the coin is, and how and where to look up its provenance. He zeroes in on the abbey of St. Jarlath’s, which happens to be reasonably close by.

Rhys is reluctant to tell Joram why he’s so interested in this possibly-not-even-still-living monk. Joram is alarmingly curious. Finally Rhys breaks down and tells him who the monk is.

Joram is shocked, but immediately and totally gets the political implications. Rhys isn’t sure he wants or dares to tell the monk he’s the long-lost heir of the deposed human dynasty. Joram is all coy and arch and political, not to mention indulgent toward the nonpolitical Rhys’ all too political dilemma.

Joram, it’s clear, is a man of action. He and Rhys set off immediately, at the gallop, to find Saint Jarlath’s. (Joram shares the future Morgan’s predilection for sexy riding leathers.)

It’s still raining copiously when they reach the monastery. Joram pulls serious rank to get them in.

They’re escorted to a reception room. Rhys is coming down with a cold. Joram hardly has a (very blond) hair out of place. The abbot arrives along with their earlier escort, who has brought dry clothes. They exchange courtesies, and then Joram talks his somewhat gradual way around to asking to see, right then and there, the abbey’s records of postulants in the order. He stretches the truth a fair bit in the process. Rhys abets him, and stresses that they have to find this monk—grandfather’s dying wish, badly wanted and needed prayers for his soul, etc., etc.

The abbot obliges, with some slight skepticism, and gives them access to the archives. Once they’ve made it that far, they go into full detecting mode, extrapolating the possible dates of the grandson’s admission, and working their way through a considerable number of Brother Benedicts.

They end up, after several hours, with thirteen possibilities. Then they have to search the death records to find out if any of them has died. By dawn they’re down to five, none of whom is here at Saint Jarlath’s.

They discuss what to do next, and where to go. There’s no question of getting anyone’s permission to do this, though one would think Joram would be answerable to some ecclesiastical authority. They’re just doing it.

Joram makes it real to Rhys by burning their notes. What they’re doing is treason. They’re hunting down the rightful heir to a usurped throne. Joram points out that the heir could be even worse than Imre. Rhys never even thought of that.

Joram has thought of all kinds of things. The Michaelines are not fans of King Imre. But they’re not quite on the verge of rebellion, either.

Rhys asks Joram if he’ll tell his fellow Michaelines. Joram allows as how he might eventually have to. But if he tells anyone, he’ll tell his father first.

Now that they’ve sort of kind of started a revolution (presuming Cinhil turns out to be “suitable”), they do what wise men do, and go to bed.

And I’m Thinking: Oy, that prologue. It’s trying so hard to be High Fantasy, and alternate history, and previous-trilogy historical background, when all I want is, you know, some story.

Then we get a whole lot of backstory and historical analysis and repetitive political exposition. But we also get an actual functional female with a working brain and an interesting personality, and that’s a huge advance over the first trilogy. I mean, huge.

For me the story really starts when Rhys shows up. He’s quite as vivid and lively a character as Duncan or Derry, and old Dan actually doesn’t have a brogue, which is a nice bonus. And then we meet Joram, who is fully as sexy as Morgan, but with far more apparent maturity and moral fiber.

He’s terribly footloose and fancy-free for a member of a military religious order, and he’s quite happy to buckle the swashes, even in the pouring rain. I didn’t remember Joram as being nearly this adorable. He’s ever so much less annoying than Morgan, though it’s early days yet.

He and Rhys are certainly quick to get cracking with old Dan’s information. The reason for it isn’t what you might expect of epic fantasy—the Deryni king isn’t oppressing the people with magic, he’s taxing them into open revolt. It’s all rather Realpolitik, which fits the dryly academic tone of the Prologue and the complexity of the political background.

But oh, they’re pretty while they’re talking about people and situations that we as readers haven’t had time to care about yet, and they’re ever so ready to leap on horseback and gallop off wherever their data and their fancy take them. That’s the Katherine Kurtz we know and love, with her lovely blond hero and this time, for variety, a nice cuddly redhead who is—bonus!—a magical healer. We just know that’s going to be important as the story goes on.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, a medieval fantasy that owed a great deal to Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni books, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Forgotten Suns, a space opera, was published by Book View Café in 2015. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies, some of which have been reborn as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed spirit dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.