Advertisement

Answering Your Questions About Reactor:

Right here.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Everything in one handy email.

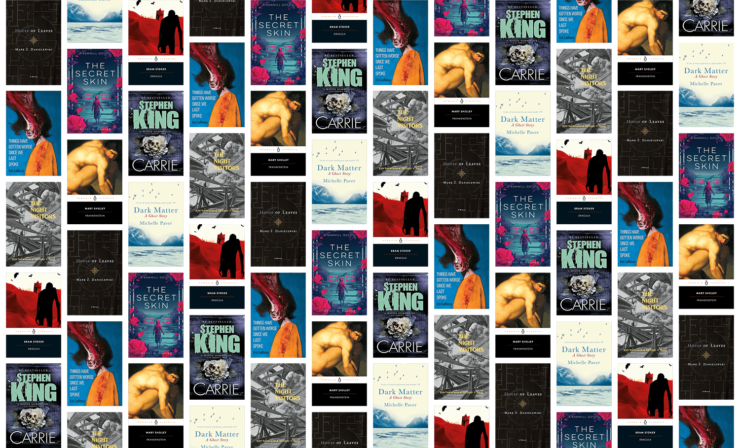

Eight Chilling Takes on Epistolary Horror

Latest from Emily Ruth Verona

Showing 2 results

“You want stories?" Thom Merrilin declaimed. "I have stories, and I will give them to you. I will make them come alive before your eyes.”

Robert Jordan, The Eye Of The World