The stakes don’t get much larger than Outer Wilds.

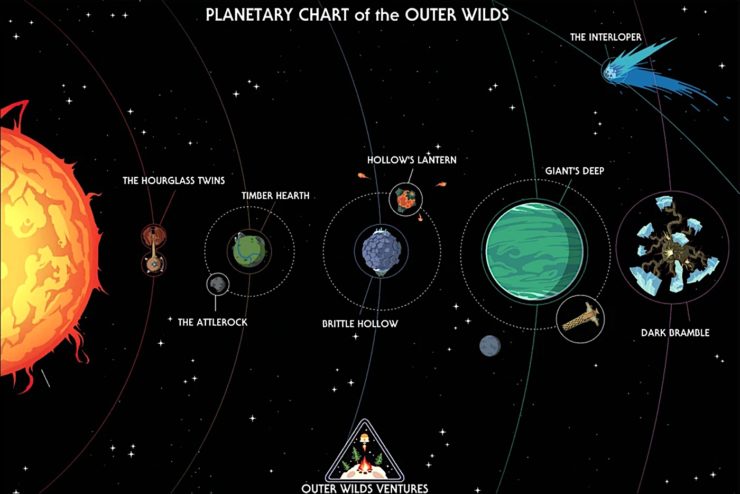

You play as a plucky young adventurer, starting your first exploration as a spaceship pilot for Outer Wilds Ventures. Born on the blue-green planet Timber Hearth, where you and your fellow Hearthians live in a cozy village with a thriving space program, you soon lift off to explore each satellite and find the ruins and remains of an ancient, alien species—the Nomai—who built most of the advanced technology that exists in this solar system. A solar system that, by the way, turns out to be dying. After 22 minutes of exploration, no matter what you’ve done, the sun supernovas, destroying every planet and creature, and you ricochet backwards in time to the moment you woke up that morning. So, you try again. It’s a huge, optimistic adventure about exploring a universe that seems to be ending. And it’s also a tiny, intimate tale about finding fellow explorers playing instruments alone around far-flung campfires on different planets, space-Western-style.

Videogames are great at being enormous and intense, and they’re great at being intimate and cozy. When we are very lucky, we find a game like Outer Wilds, which is both at once. This is also what excellent space opera tends to be—asking huge questions, but couching them in tiny, human-to-human connections. Philosophically vast, but snarky and personal. Intimate community plus vast, empty space.

[Spoilers ahead for Outer Wilds, which you really owe it to yourself to play]

Let’s start with the small. When we’re reading or watching a space opera, the characters’ predicaments, no matter how dire, will wrap themselves up by the final page or shot. We can drink our hot beverage of choice and eat our snacks, safe on Earth, illuminated by the glow of risky heroics that ask us only to cheer them on from afar. Space operas tend to have a clever ensemble cast, full of characters we might quite like to befriend or seduce. We feel a bit like we, too, are part of this ensemble, tuning in to visit our friends on the Rocinante or the Wayfarer. But we know we aren’t, really, a part of the gang.

In games, we can be. And so, in games, we reap the glory and the disappointment of succeeding at those risky heroic maneuvers—or not. Games tend to be less quippy and sardonic than a space opera you watch or read, since you are playing as the hero, and you may not feel a clever quip come to mind the seventeenth time you accidentally smash your spaceship to bits on the rocky side of an unremarkable planet. The failures might just be boring accidents, not building up into any great narrative. When the Millennium Falcon needs repairs and hides in the cave on the asteroid, the romantic narrative is forwarded (“you like me because I’m a scoundrel”) and then, after the horrifying reveal that their cave is actually an alien’s gullet, the stakes of the primary narrative spur—find safe haven—rachet up, compelling them to (disastrously) try their luck with Lando in the Cloud City. Problems happen because the story needs them to happen, and they get worse because the story needs escalation. When our spaceship needs repairs in Outer Wilds, it’s just because we messed up, and now we need to fix it.

Luckily, it’s easy to fix. Timber Hearth’s aesthetics are casually Solarpunk. We live in a lush, thriving, community-oriented, maker-culture powered by local plant-based solutions and ancient found technology. We travel in a rinky-dink spaceship that seems like it should barely be able to get off the ground, surrounded by wooden (but somehow not flammable) slats. While our species has recently taken to space travel, we have not left our arboreal roots behind.

With its hunk-a-junk spaceship, Outer Wilds gestures towards the “used future” aesthetic popularized by Star Wars, Firefly, and plenty of other ensemble-cast space operas, in which a scrappy group of ragtag misfits manage to keep their unimpressive-looking ship flying. The used future is typically pretty gritty, full of hard-scrabble veterans and secret (or not-so-secret) rebels to the Empire/Alliance (some kind of enormous federation government that controls the galaxy, operated by sharply-attired military personnel on shiny new spaceships quite different from our heroes’). We root for the rebels, who are funny and charming, never losing their cool in the midst of an impossible stand-off. The rebels are good-hearted criminals living payout-to-payout, holding it together with sweat and humor; the Alliance have a vast hierarchy, a punishingly strict system, endless resources, and top-of-the-line advanced equipment. The rebels are a found family; the Alliance are a fascistic corporation.

But part of what’s so joyfully cozy about Outer Wilds is that the rough role of the “Empire” is taken by the Nomai—an alien species of brilliant scientist-explorers, who came to this solar system long ago on what was essentially a spiritual quest. They heard a signal from the Eye of the Universe, so they traveled here on their shiny spaceships to investigate. They then spent several generations settling on the planets, conducting experiments, and leaving written records of their conversations and lab squabbles in a textured, spiraling script that the player character has only just co-invented a technology to translate. Armed with this translation gun, the PC can roam the solar system, tracing out the intellectual journey of the Nomai scientists and slowly connecting the dots between their experiments, projects, and realizations.

Though the Nomai achieved technological prowess far beyond the capabilities of the humble Hearthians, though the Hearthians are using found pieces of Nomai tech to hurtle themselves into space in their tin-can spaceships, the used future we find in Outer Wilds is inordinately friendly, gentle, and collaborative. The Nomai are long gone, and when we begin the game, we have no idea why. We find the record of their knowledge as we explore and, eventually, piece together what happened to them. But at no point do we feel threatened by this vastly superior species. The “Empire” here is benevolent, curious, flawed, and very funny in their own way. The Nomai conversations, etched on walls, are studded with not-very-funny puns (for instance, in a conversation between 3 Nomai miner-geologists, one quips, “if they’re sealing off all entrances, I hope they’ve planned a-core-dingly!”) When we boil down enough of these Nomai conversations, we find adorable, 3-eyed teddy bears with curious natures and kind hearts. Far more Star Trek than Star Wars.

Gradually, you realize that the ensemble cast is composed of multiple species and even planets. The ensemble includes you, your fellow Hearthians at home and playing their instruments around foreign campfires, all the Nomai scientists who came long before you, and, in the DLC, another species of alien. Even the geologically hyperactive satellites you land on, with whom you spend more time than with any sentient creature, come to feel like found family. You feel curious, loving, excited to spend more time with them. You really want to learn enough to save them all. To figure out why the sun keeps exploding, why you keep looping backwards in time, what you could do differently in the next loop to fix it.

Here’s where things get very large. Because you cannot save it.

This is what playing a space opera can give you that watching or reading a space opera cannot. When you have looped and looped, trying again and again to save your beloved world and it just can’t be saved, you are left with something that becomes a spiritual experience. You see the end of the universe coming, and you fight your way towards acceptance—discovering, rejecting, vowing to avert, pleading with, grieving, and ultimately welcoming and pressing the trigger to incite.

And the thing is, it’s not your fault. You can’t fix it, but you also didn’t cause it. It’s not like the spaceship, where it’s broken because you crashed it. It’s broken because it’s broken, and you’re just here to learn. It cuts against the grain, to lose your agency to fix things, in an artistic genre that is all about fixing things. This tension is deeply encoded in the game, built into the 22-minute time loop that structures the whole experience. This kind of time loop in a videogame—where the player is returned to a previous save point whenever they die—is such a normal genre convention that it tends to fade into the background, the way we don’t notice how weird it is that the actors on a stage don’t see or hear the audience. If we think about it, we realize it’s more than a bit uncanny, which is why we mostly don’t think about it.

So, when we start playing, we assume that’s all it is. I failed; ok, cool, now I get to try again! I can keep trying until I win. This is how games work. But in Outer Wilds, the temporal loop is built into the universe. It’s not a result of player ineptitude. You cannot live longer than 22 minutes in this solar system; if nothing else kills you, the sun will. There’s a plan for failure. This, in fact, IS the plan for failure. The Nomai anticipated this precise future, when the sun would supernova, and built in this time-looping mechanism for pausing the end of sentient life in the world, like a record intentionally scratched, so that the song won’t ends without intervention. It’s been carefully, meticulously constructed. When you finally accept it and choose to end the song, it doesn’t feel like failure at that point. It just feels like love.

Melissa Kagen researches and teaches interactive storytelling, TTRPGs, escape room design, immersive performance, and critical game studies at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. She got her PhD from Stanford, and her first book, Wandering Games, is out now from MIT Press. She likes biking, eating vegan food, and accumulating notebooks. You can find her online at her site and on Twitter.