As we reach the end of another year, it’s time to look back at some of our favorite non-fiction articles from 2022! As you may have guessed from the title, this year we’ve decided to break with tradition and split the list into two halves. This first piece features some of our favorite articles about books, reading, writing, and storytelling, while the second half will highlight articles about TV, film, media, and popular culture.

While both lists are focused on standalone essays and articles, we’d also like to highlight our wonderful lineup of regular columns, along with the amazing array of fiction recommendations from longtime contributors Alex Brown, James Davis Nicoll, and Jo Walton. This year saw several beloved series come to a close, including Matt Mikalatos’ Great C.S. Lewis Reread (which ended with this heartfelt farewell) and Judith Tarr’s epic Andre Norton Reread, while SFF Equines has expanded into new territory with the SFF Bestiary (also written by Judith Tarr)! We’ve also added some new book-focused series into the mix with Cole Rush’s Please Adapt column and Jenny Hamilton’s Ships in the Night.

We hope that you enjoy the selections below, and since these are just some of our favorite book-centric essays from the last twelve months or so, please feel free to tell us about the articles and columns that have stuck with you and/or made you smile this year!

Selections From Guest Editor R.F. Kuang

This year, we welcomed our first Guest Editor, R.F. Kuang, the author of the Poppy War trilogy, as well as a scholar and translator who has been a tour-de-force in the speculative fiction community. Over the course of the year, Kuang curated a series of fascinating essays that touched on everything from humanism and philosophy in science fiction storytelling, approaches to interpreting and engaging with living myths, to rethinking the history and the future of writers’ workshops. You can find the full series here.

Fighting Back Against Book Banning and Censorship

Book Bans Affect Everybody — Here’s How You Can Help by Alex Brown

I have been a librarian for more than a decade, and a school librarian for nearly half of that. I didn’t get into this field to wage a war against a political system that has declared me the enemy. All I wanted to do was to make fun displays, teach teenagers research skills, and provide them a vast array of books to act as what the inimitable Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop called “windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors.” Yet here we are in the middle of a fight that will have devastating long term effects regardless of who comes out on top.

I’m exhausted, afraid, and frustrated. But mostly I’m angry.

Book bans aren’t new, but we haven’t seen this kind of surge in years. In 2020, 156 challenges, censorship attempts, and bans were reported to the American Library Association; in just the last three months of 2021, 330 were reported. Countless more skated under the radar or weren’t reported to ALA at all. This new wave hit hard and fast and shows no sign of abating.

On the Importance of Art Spiegelman’s Maus by Leela Corman

It’s January, 2022. The McMinn County School Board votes to ban Art Spiegelman’s Maus because of its “use of profanity and depictions of nudity”. Among the specific objections were board members saying: “…we don’t need to enable or somewhat promote this stuff. It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy…” and “…a lot of the cussing had to do with the son cussing out the father, so I don’t really know how that teaches our kids any kind of ethical stuff. It’s just the opposite, instead of treating his father with some kind of respect, he treated his father like he was the victim.”

Do I need to remind you what Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking comic Maus, is about? Of course it is about his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz, a Polish Jew like my family. It’s about something else, too. Something you’d only know about if you’re like my family.

The Books We Read as Children Always Change Us — Let’s Embrace It by Kali Wallace

The fact that books change us shouldn’t be scary. It isn’t scary, not unless you are terrified of other people, such as your children, having ideas that you cannot control. Sometimes it’s unsettling, and sometimes it’s uncomfortable. It’s very rarely straightforward. But it’s also splendid, because while we only ever get to live one human life, books offer up infinite experiences to anybody who goes looking. We should be able to talk about this—about ourselves and about young readers—in a way that isn’t dictated by idiots who believe that a picture book about an anthropomorphized crayon represents society’s worst degeneracy.

Reevaluating Classic Science Fiction

William Gibson’s Neuromancer: Does the Edge Still Bleed? By Eileen Gunn

My favorite part of reading a work of science fiction for the first time, like visiting a new country, is that hit of strangeness, of being someplace where I don’t know the rules, where even the familiar is unsettling, where I see everything with new eyes.

In 1984, Neuromancer delivered that to me. I read the book in small bites, like one of those sea-salt caramels that are too big and intense and salty to consume all at once. The first few chapters are especially chewy: I like the almost-brutal profligacy of the prose, new words and ideas cascading out of the book fresh and cold as a mountain torrent, and be damned if you lose your footing. The opening vision of an assaultive future is wide-ranging and obsessive, as if the narrator, dex-driven and frantic in Chiba City, just can’t turn his consciousness off. Everything he sees has layers of meaning and speaks of the past, the present, and the future all at once.

“The Screwfly Solution” Captures the Violence of Our Current Moment by Nic Anstett

Few stories have rattled me the way “The Screwfly Solution” did the first time I read it this summer. I encountered it on the morning after yet another mass shooting, during a season punctuated with anti-trans legislation and the stripping away of reproductive rights. I was syllabus-building for a course on speculative fiction and the gender binary and had already filled the reading list with most of the heavy hitters and personal favorites like Le Guin, Butler, Delany, Anders, Fall, and Gimpelevich, but I knew that Sheldon/Tiptree had to make an appearance. “Screwfly” was at first one of many potential stories, but after my first read and the long, unsettled hours that followed, I knew that this was the story I needed to teach. The story that felt fundamentally of this moment.

Recontextualizing Classic/Epic Fantasy

Our Country: C.S. Lewis, Calormen, and How Fans Are Reclaiming the Fictionalized East by Nasim Mansuri

How do you love a book that hates you?

I read page after page about Lewis, trying to get a glimpse of what he really thought; who he really was. I read through Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters almost obsessively, as if they can explain Tash as anything other than a demon, or the Calormenes as anything other than villains—as if Lewis’ universe could ever reconcile Aslan and Tash, his culture and my culture, his vision and mine. As if there is a page somewhere where he explains why he wrote things this way—where he tells me he really loved Calormen all along.

On Remaking Myths: Tolkien, D&D, Medusa, and Way Too Many Minotaurs by Jeff LaSala

…[M]yths are a way to see where a group of people came from—historically, culturally, psychologically. They’re stories from somewhere out of the past (or at least written like they were, like Tolkien’s) that have societal meaning and staying power. By their very nature, they’re meant to be retold, recast, and revisited—perhaps even refurbished or reupholstered? But they are fluid things; they change as we do, and as the world does. And we’ve been retelling myths since the first was spoken out loud. It’s just in our DNA. As soon as one person finishes telling a great origin story, someone else runs off and tells it to another, kicking off the everlasting, humanity-spanning game of mythological telephone that we still enjoy today. Heck, some myths are about how such stories even get started and spread.

A Song of Ice and Fire Is a Horror Story That’s Been Lost in Translation by Tyler Dean

During the airing of the final season of Game of Thrones, I wrote a pair of articles for Tor.com on ASoIaF and the Gothic; the Gothic, of course, closely borders and often overlaps with horror, but where both the original series and House of the Dragon bring Gothic sensibilities to the forefront, out-and-out horror is often diminished or relegated to a few key plot points. In this essay, we’ll look at the various way in which horror is central to Martin’s books—through pervasive misinformation, a repeated focus on cursed and desolate spaces, the ways in which magic is used exclusively as a terrifying and destructive force, and even the repeated Lovecraftian references that Martin cannot help but inject into his books.

Personal Essays About Recent SF

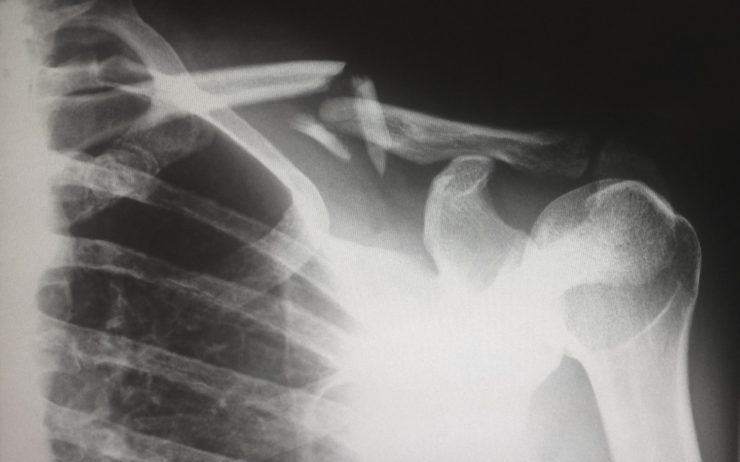

Disturbing the Comfortable: On Writing Disability in Science Fiction by Nathanial White

Six years ago I shattered my spine in a whitewater kayaking accident. The bone shards of my second lumbar vertebra sliced into my spinal cord, severing communication with the lower half of my body. Surgeons rebuilt my vertebra and scaffolded my spine with four titanium rods. I spent a year in a wheelchair. After hundreds of hours of therapy, my body established new neural connections. I learned to walk again. I’m tremendously grateful, and I know it’s an inspiring story. It’s the story that many want to hear. But it’s not the story I want to tell in my writing. […]

I decide I need a more encompassing narrative, one that considers exasperation as well as progress, suffering as well as triumph. One that makes meaning not just from overcoming, but from the ongoing lived experience of pain. Maybe I can even exorcize pain through writing, transmute it into narrative. So I invent Eugene, the protagonist of my novella Conscious Designs. I give him a spinal cord injury. Maybe together we can find some sense in our suffering.

Tamsyn Muir Understood the Assignment: The Locked Tomb Series’ Expansive Exploration of Death and Grieving by Emma Leff

I first read Gideon the Ninth in the summer of 2020, maybe a month after my dad had died suddenly and also, of course, in the middle of a deadly global pandemic. In that moment, I wasn’t actively seeking out material that reflected that part of my lived experience. Mostly, I saw “lesbians” “swords” and “memes” and thought “yes please!” Quickly, the books captured my heart and imagination. But not until later, reading, “As Yet Unsent: Cohort Intelligence Files” the bonus chapter released with the paperback edition of sequel, Harrow the Ninth, that I began to think of the series as an evolving inquiry into the nature of death and dying, what it means to be left behind. And speaking from experience, one thing is absolutely clear: Tamsyn Muir understood the fucking assignment.

Murderbot: An Autistic-Coded Robot Done Right by C.N. Josephs

As an autistic lover of sci-fi, I really relate to robots. When handled well, they can be a fascinating exploration of the way that somebody can be very unlike the traditional standard of “human” but still be a person worthy of respect. However, robots who explicitly share traits with autistic people can get… murky.

The issue here is that autistic people being compared to robots—because we’re “emotionless” and “incapable of love”—is a very real and very dangerous stereotype. There’s a common misconception that autistic people are completely devoid of feelings: that we’re incapable of being kind and loving and considerate, that we never feel pain or sorrow or grief. This causes autistic people to face everything from social isolation from our peers to abuse from our partners and caregivers. Why would you be friends with someone who is incapable of kindness? Why should you feel bad about hurting someone who is incapable of feeling pain? Because of this, many autistic people think that any autistic-coded robot is inherently “bad representation.”

But I disagree! I think that the topic can, when handled correctly, be done very well—and I think that Martha Wells’ The Murderbot Diaries series is an excellent example.

On the Power of Stories and Storytelling

Why Stories Are Dangerous — And Why We Need Them Anyway by Jason Gots

We tend to think of stories as self-contained, unchanging things with a beginning, a middle, and an end. But dreams teach us that stories are woven from fragments of memory and imagination—that the formal, written stories we know are barely contained within their pages. Once we’ve read or heard them, they forever form part of the fabric of our consciousness, informing our thoughts and our lives in ways we’re hardly aware of. Plot is important. But what we care about, what carries us through the story, is character. We’re humans, after all—mammals—wired from birth to care about how other humans feel and what happens to them.

How to Be a Protagonist When You’re Not the Chosen One and the World is Unsaveable by Samit Basu

You’re having trouble really fitting into your protagonist role. The world you’re in looks like it can’t be saved. Nobody’s declared you the Chosen One, and your attempts to self-declare seem a little off to the people around you, or even to yourself. Don’t worry, we’re here to help.

First of all, congratulations for experiencing a moment of self-doubt. The people who automatically see themselves as the one true centre of the universe, assign enemy/sidekick/lover/backstory/NPC roles to everyone else, and then set off to destroy something are usually the problem. If you’re not them, you’ve already made the world better…

By making the connection between dreaming and storytelling explicit (as Shakespeare does repeatedly throughout his work), Gaiman reminds us that our lives are afloat on this ocean of narrative. Out of it, we spin the stories of who we think we are. We get caught up in other people’s stories of themselves and the ones we tell about them.

Finding Comfort in the Horror of Stephen King’s Maine by Elizabeth Austin

My Maine is not a postcard Maine. It’s not anything you’d send home to your mother. I wasn’t searching for the perfect panoramas from the bubbles of Acadia. […] I wanted the overgrown paths through the dense woods where you can lose yourself even when you’re careful, even when you think you know the way. I needed the hard truths I had been raised on, the ever-bubbling water in the lobster pot in which each evening we boiled animals alive and then ate them, relishing in their sweetness. In Stephen King’s books I found the deep forests of my grandfathers and the ghosts of the Maine men who passed their Maine blood on to me.

A Modest Proposal for Fans of a Very Particular Kind of Story

What Is “Curio Fiction”? Finding a Name for a Fantastical Subgenre by Diane Callahan

There’s a particular subgenre of speculative fiction that scratches an itch for me like no other. It’s where you find yourself in a world very much like our own, except one thing is slightly… off. […]

What all these stories have in common is that they explore human relationships and daily life through the lens of an often-singular or anomalous speculative element. Although terms like magical realism, fabulism, low fantasy, soft sci-fi, and light speculative fiction already exist, I don’t think any of these adequately encompass the narratives I’m talking about—the type of fiction I want to devour as a reader and replicate as a writer. That’s why I suggest a new subgenre label: curio fiction.

Mark as Read

Finally, we just want to take a minute to celebrate Molly Templeton’s Mark as Read column, which started last year and has continued to be one of the highlights of each week, giving readers a place to talk about the things that connect us (and occasionally frustrate us) as lovers of books. Over the last twelve months, the column has explored the potential benefits of setting reading goals, the deeply personal art of organizing your books, the possible causes of series fatigue, the times when we need to embrace the most heartbreaking books, and the surprise we feel when a book sneaks past our usual preferences and preconceptions to defy our expectations. You can find the full list of columns (and the conversations they’ve inspired) at the series page, here.

***

That’s all for now, but you can now read the second half of our list, where we talk all about old and new movies, TV series, and other pop culture favorites. In the meantime, if you’re feeling nostalgic, you can always check out our “Some of the Best…” article round-ups from previous years: 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, and 2017. Happy reading!