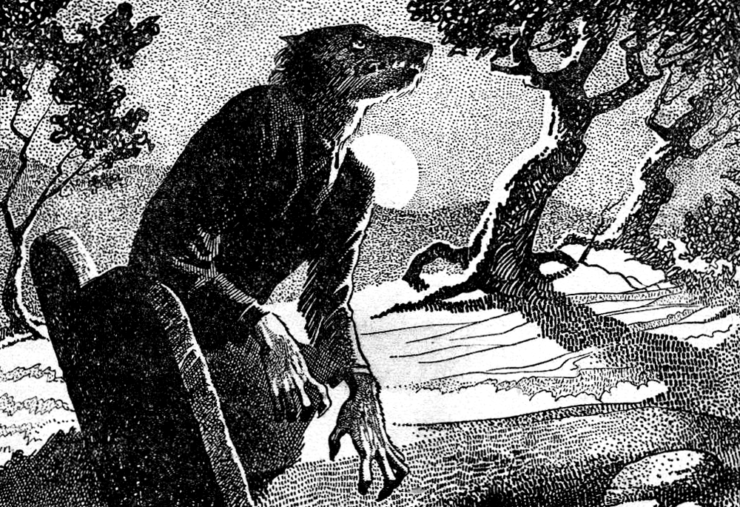

As iconic as the unicorn and the dragon are to the fantasy bestiary, the werewolf is to horror and urban fantasy. It’s at least as old in the human imagination, and arguably in literature. There appears to be a werewolf in the oldest epic poem we know, the Epic of Gilgamesh, though somewhat tangentially: a woman is reputed to have transformed one of her lovers into a wolf.

Ancient Greece (and its Roman poetical followers, Ovid of course included) had the legend of Lycaon, transformed by Zeus into a wolf. Non-Greek-fanfictional Rome took a different tack, touching on another archetype, the human child adopted by a she-wolf. Romulus and Remus remained human and became the founders of Rome. Lycaon on the other hand died for his sins.

It’s interesting to see how these two strains carry on into the modern imagination. They both reveal a perennial preoccupation with this particular apex predator. Long after a subset of wolves joined humans as friends and partners, the wild wolf lived on, arousing both fear and admiration.

There’s truth in the foster-child narrative, multiple examples of children raised by wolves. Unlike the Roman twins, or for that matter Kipling’s Mowgli, the outcome has not generally been positive. A child raised without human language never fully develops it, and seldom if ever integrates into human society.

The werewolf is literally a different animal. He—it’s preponderantly male—is born and grows up human, but at some point, something triggers the transformation. In Gilgamesh as in many later examples, it’s a curse. Lycaon is sentenced to it by a god, for the murder of his own son.

In later examples, man transforms into wolf for both allegory and entertainment. Scholars in the Western Middle Ages from Augustine onward were fascinated by the concept. Did the wolf retain a man’s mind? Or was it a case of demonic possession, whether the transformation was literally from human into animal, or psychologically with the person retaining human form but believing himself to be a wolf? Or maybe it was a way of depicting the effects of uncontrollable rage, analogous to the berserkers of the North—men who opened themselves completely to the lust for blood, without actually transforming into animals.

Whatever the reason or the result, the werewolf persisted in song and story, all the way to the modern era. How he (or, in later examples, she) manifests will vary depending on the source. The connection of the werewolf with the moon has become canon, but it’s a late development. There’s a suggestion of it in Petronius’ Satyricon, if you read it in a particular way: a reference to the brightness of the moon. For the most part, up until the twentieth century, the transformation arises out of either direct magical intervention (spell or curse) or the victim’s psychological state.

Tying it to the moon simplifies it in terms of plotting. If your curse only affects you three days each month, you have the rest of the month to try to live your life and/or figure out how to break the curse. You may end up locking yourself into a nice sturdy cage a la Oz in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or you embrace your dark side and join a hunting pack, for good or ill depending on which universe you live in.

The werewolf in general, through the ages, is more a villain than a hero. Even when he’s a victim, while he’s under the influence of the spell, he’s pretty much pure predator. He represents the dark side of human nature. He rages and kills without restraint. He’s literally dehumanized, stripped of reason and empathy and bereft of compassion.

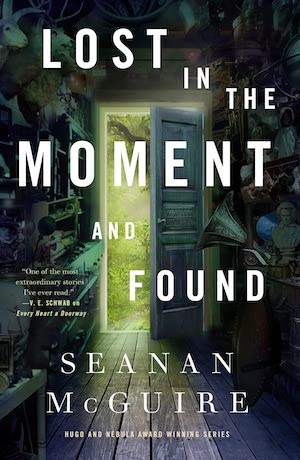

Buy the Book

Lost in the Moment and Found

He is, at base, a manifestation of human fear and hatred of the wolf. These days we see the species in a much more positive way, as a beautiful animal with a strong social structure. Wolves among themselves show many traits that we as humans admire.

That is a sign of privilege. We’ve driven wolves to near-extinction, relegating them to the distant margins of our world. We can spare them our empathy, because we’re not competing for food, territory, and plain survival.

When wolves and humans have to coexist on more equal terms, it’s much harder to see the wolf’s side of the equation. For a hungry wolfpack, if you are out alone or unprotected, you are dinner. If you’re in a group or in a guarded shelter, the wolves will come after your livestock. The wolf is the enemy. If you don’t kill him, he’ll kill (and probably eat) you.

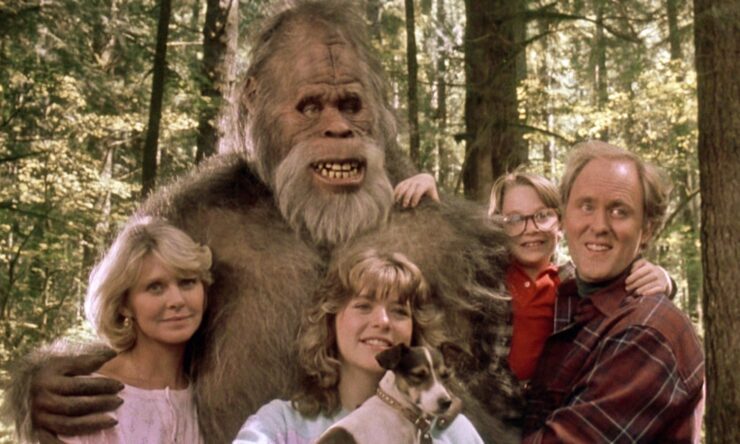

Wolves are smart. They’re strong. They hunt in packs. They’re enough like humans in their social organization that it’s possible to project human hopes and fears onto them. From there it’s not too far a leap to imagine the transformation of human into wolf.

It’s interesting that the opposite transformation hasn’t had much traction. Man into wolf, early and often. Wolf into man, vanishingly rare. I suppose it’s part of the human predilection for regarding animals as inferior beings. We can devolve into the savage beast, but the savage beast can’t become one of us. I’d love to know if there are examples—written or filmed—of wolf-to-human shifters. Surely there must be some, somewhere?

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.