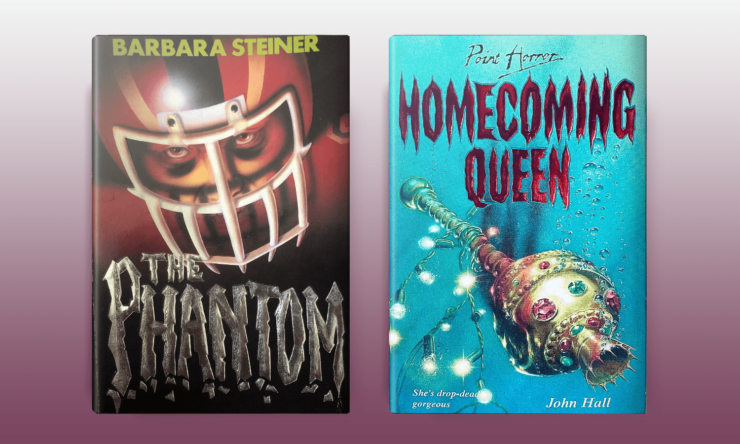

As the leaves turn and the nights get colder, ‘90s teen horror fancies turn to football games under the Friday Night Lights and who will be honored with a spot on the homecoming court. In both Barbara Steiner’s The Phantom (1993) and John Hall’s Homecoming Queen (1996), the school spirit is literal. In The Phantom, the students of Stony Bay High begin seeing the ghost of Reggie Westerman, the high school quarterback who died the year before as the result of football injury, while in Homecoming Queen, Brenda Sheldon is the eponymous queen, returned from the dead twenty-five years after dying on homecoming night and apparently angry that Westdale High is reviving the homecoming queen tradition.

While much of each novel focuses on the teens trying to figure out if these ghosts are actually real—and if they’re not, who’s pretending to be them and why—The Phantom and Homecoming Queen both also reflect upon the way teens grieve and cope with death, particularly the loss of one of their own.

In The Phantom, Stony Bay High School was profoundly shaken by Reggie’s death and his absence remains palpable almost a year later. His teammates remember him fondly, his brother Travis strives to commemorate him, and his girlfriend Jilly is still struggling to move on, mired in depression, not quite fitting in with her peers, spending time with a new guy named Shelby, and unsure about whether she wants to cheer again. Reggie’s friend Garth’s grief is also partially guilt, as he holds himself responsible for not blocking the hit on which Reggie was injured, and Amelia isn’t really up to the challenge of coping with the combined struggles of her best friend (Jilly) and her boyfriend (Garth). But it’s a new year and a new football season … until Reggie shows up at the pep rally. As the students, players, faculty, and staff are all gathered together in the auditorium, the curtain opens and “Standing in the vaporous mist, circling and floating around it, the figure looked ten feet tall. A menacing hulk, shoulders padded to gigantic proportions, it loomed over the stage” (7). The ghost’s face isn’t visible, hidden beneath its helmet and the “bony, skeletal mouth” (9) of the facemask, but it’s wearing Reggie’s jersey and the crowd begins to scream in terror, all of their anguish returning, all of their healing undone.

Even more horrifying than the appearance of the ghost itself is Coach Paladino’s response, as he immediately capitalizes on Reggie’s return to drum up fervor and enthusiasm for the team, proclaiming to the gathered crowd that “He could not stay away … Our hero, who could not be with us here in reality, has chosen to remind us that he is with us in spirit” (11), before dedicating the season to Reggie’s memory and coining a new cheer, to “Win for Westerman!” (12), which the spectators immediately pick up and begin shouting in response. This is crass and exploitative, and while the school as a whole is swept up in the excitement, there are a few voices of reason mixed in with the clamor, including the drama teacher, Mrs. Hodgekiss, who suspects Coach Paladino of staging the whole thing, calling it “a cheap trick, totally without taste, unforgivable … using Reggie Westerman like this is sick” (23, emphasis original). Coach Paladino denies responsibility, but that doesn’t stop him from leaning into the drama and excitement, as he feeds into the suspense of waiting for the ghost’s next appearance.

A cloud of suspicion hovers over Coach Paladino for much of The Phantom, as he and the team work to build a winning season around Reggie’s legacy, and Steiner doesn’t shy away from the possibility that an unscrupulous person might capitalize on a young man’s death. She’s also unflinchingly realistic about the culture of competitive athletics. While the teens celebrate the football team’s successful season, cheering them on with enthusiasm and valorizing their gridiron heroes, the threat of injury and the fact that everyone is replaceable never really fades into background. Reggie sustained a spinal cord injury in his final game, falling into a coma before dying a couple of weeks later, and his friend Garth, who was on the offensive line, still blames himself for not protecting Reggie from that hit. The fans’ allegiance is fickle and while they were swept away in remembering and honoring Reggie as they cheered to “Win for Westerman!” at the pep rally, when their new quarterback Buddy Nichols takes the field, this chant is quickly abandoned as they forget “Westerman” and scream “Nichols” instead (their enthusiasm and support for Buddy is just as quickly abandoned a couple of weeks later when Buddy is injured and Garth becomes the starting quarterback). Watching from the sidelines as one of the players collapses and is taken off the field, Amelia sardonically notes that “There was no announcement. Nothing. A rookie player took Frank’s place and the game resumed. What was one player down? There was always another to take his place” (131). This is a harsh reality but one that Steiner addresses head on, foregoing the urban legend approach to the ghost story to instead consider who stands to gain what from Reggie’s reappearance and the lengths to which they might be willing to go to get it, whether it’s a winning season or the chance to take the field as a starter, to be a hero.

The pressure on student-athletes to perform is also central to the drama of The Phantom, as Amelia discovers that one of the reasons Reggie wasn’t playing at his best and wasn’t quick or mobile enough to evade that final hit was that he had been drinking before the game, a habit that he had gotten into to deal with his nervousness and the pressure to be the best. Alcohol as a teenage coping mechanism doesn’t get nearly the attention it deserves here, though Steiner addressing it at all is notable. Garth knew about Reggie’s drinking but Coach Paladino didn’t, an important—if brief—recognition of the ways in which adults often remind blind to or oblivious about the emotional and psychological intensity of teenage experiences.

While Coach Paladino takes advantage of every opportunity that comes his way through Reggie’s sensational reappearance, he’s not actually behind it. While Reggie’s death was tragic, most of his peers have processed their grief and moved on, but not Reggie’s girlfriend Jilly. Amelia is Jilly’s best friend, though from the novel’s opening pages, readers get the sense that she might not be a very good one, as she responds to Jilly’s lingering grief with annoyance, impatience, and anger. As far as Amelia is concerned, Jilly needs to get over Reggie’s death, get back to “normal,” and stop being such a downer. When Jilly tells Amelia that she can’t bring herself to go to the pep rally and is going home instead, Amelia’s response is dismissive and cruel, as she tells Jilly “Okay, fine. You do that. You go home. Go back into the self-pity you’ve enjoyed for almost a year. I can’t help you anymore. I don’t even want to try” (2). With friends like these, Jilly’s infatuation with this imagined past, her perfect boyfriend, and her conventional teenage life is a lot easier to understand. While Jilly remains preoccupied with the past and Amelia is frustrated with Jilly for not living in the present, Amelia’s expectations of who she wants Jilly to be are ironically grounded in their shared past as well: she wants everything to be exactly the same as it was, just without Reggie. She drags Jilly to all the old places where the two girls used to go on double-dates with Reggie and Garth, wants Jilly to keep doing cheerleading because “we’ve always done everything together” (29), and refuses to see the impact Reggie’s death has had on Jilly or accept any change in her friend. Jilly has come to the realization that the only way for her to move forward is along a different path, but Amelia keeps putting up roadblocks, desperately trying to steer Jilly back to the old one, with disastrous consequences.

Jilly can’t retreat into the past and finds herself unable to move forward either. She attacks and injures the players she sees as trying to replace Reggie, confessing that she was driven by the need “to keep [them] from stealing Reggie’s place … Everyone would have forgotten Reggie” (193). Jilly is behind the appearances of Phantom Reggie, donning pads and his football uniform, using dramatic lighting, fog machines, and in one particularly memorable appearance, scuba gear–and anything she was unable to do herself, she conned her new friend Shelby into doing for her. Shelby has been another bone of contention between Jilly and Amelia: Jilly has seemed to be interested in him and has spent a lot of time with him, a potential new boyfriend who Amelia disapproves of because he’s a drama kid rather than a jock, not really fitting in with their crowd. Just as Amelia attempts to force Jilly into being the old Jilly, Jilly herself tries to fold Shelby into her existing life, dragging him along to football parties where he gets excluded, teased, and even shoved into a trashcan. Shelby is supportive and a good sport, willing to do whatever Jilly asks of him and encouraging her to be herself, but it turns out Jilly was using him all along, manipulating him into being her accomplice and caustically dismissing him in the end by telling him “You’re so gullible … Did you really think I could love you back? Reggie will always be my true love” (194). Jilly is unable to process her grief over losing Reggie and lacks the support system she needs to help her do so, with friends who instead badger her to get over it and just get back to “normal” already. Notably, Amelia doesn’t really blame herself or take any responsibility for what happened to Jilly, instead displacing that guilt onto the “Anger, bitterness, grief [that] had stolen the Jilly she had known” (196), as Jilly climbs up to the gym rafters and falls to her death on the court below. As Amelia says goodbye to Jilly, she finds herself “wishing she could have helped her” (198), but still not facing up to the different choices she could have made or the ways she could have more effectively supported her friend, with Amelia lost instead in her own version of this grief.

John Hall’s Homecoming Queen has a similar specter, though this one lacks some of the immediacy of The Phantom. Westdale High’s last homecoming queen, Brenda Sheldon, died twenty-five years ago, so the current Westdale High School students know her through their telling of urban legends and campfire-style stories rather than being burdened with the grief and loss of one of their own. While The Phantom’s Reggie was a “real” person, someone his fellow students all knew and had memories of, Brenda Sheldon is a symbol, a cautionary tale. Twenty-five years ago, Brenda had been crowned homecoming queen, an idealized feminine figure whom “everyone liked … and when she was crowned, she looked like a princess” (15). After the homecoming dance, Brenda and her friends broke all kinds of rules and made a lot of bad choices, missing curfew, drinking, and driving out to a secret spot in the Blue Willow Woods to party and celebrate, even though it was raining, the roads were slippery, and her boyfriend Jake’s brakes needed replaced. This of course ends horrifically, in an accident that kills everyone in the car, decapitating poor Brenda. It’s a sensational story, passed breathlessly from one generation of teens to the next, and Brenda is now an almost mythical figure, both ghost story and morality tale.

When Westdale High decides to revive the homecoming queen tradition after twenty-five years, bad things start happening to nominees, sparking a rumor that Brenda doesn’t like the competition’s resumption and is back for revenge. A sandbag almost falls on Melissa’s head while she’s on the auditorium’s stage, trying out the queen’s throne just to see how she’d look, she gets threatening phone calls and dead flowers, and she sees the ghost of Brenda in the woods one night while walking home from the library, as the spirit passes on the warning “Wear the crown and you will die … die just like me” (62, emphasis original). Faith is badly burned using a tanning bed at the local gym and Tia is attacked by a swarm of bees from a hive someone shoved into a locker, attacks clearly designed not just to terrify and cause pain, but to mar these young women’s beauty. Things take a fatal turn when mean girl Betsy wins homecoming queen and then is actually murdered, her body stuffed into a dryer at the local laundromat. Instead of calling the whole thing off, runner-up Melissa is declared the new homecoming queen and is understandably a bit on edge as she goes to get ready for the dance, only to find her dress torn to shreds.

Buy the Book

Lost in the Moment and Found

While the main focus of the horror here is the reputed ghost of Brenda Sheldon and her quest for vengeance from beyond the grave, the competition for homecoming queen is terrifying enough in and of itself. In addition to the terrible “accidents” that these girls experience, there’s plenty of intimidation and bullying going on as well, mainly on the part of the popular girls, Betsy and Laurel, who harass Melissa when Lauren’s ex-boyfriend Seth becomes Melissa’s new boyfriend. This feminine competition radiates through Melissa’s friend group as well, as her steadfast friends Izzy and Celeste find Melissa’s head turned by her newfound popularity as she makes new friends, blows them off for parties, and cancels plans with them to go out with Seth instead. In the end, even Melissa, Izzy, and Celeste turn on one another, with Celeste suggesting that Izzy is the one behind the attacks in order to drive a wedge between Izzy and Melissa.

There’s also an oddly unaddressed class component to the popularity contest for homecoming queen, as each vote costs a dollar, meaning that whoever has the most financial resources and the greatest number of well-monied friends will inevitably win the crown. Melissa holds the lead for a while because she’s making new friends and her new boyfriend Seth is happy to drop a lot of cash on votes for her, but Betsy is rich and popular, with rich and popular friends, making her victory a pretty logical foregone conclusion. It takes actual murder to upset the hierarchy of entrenched capitalist dominance and the formidable forces of high school popularity. Melissa’s friend Izzy is socially conscious and a bit of a rabble-rouser—she calls Melissa out one day at lunch when she sees her eating a tuna fish sandwich to make sure the tuna brand is dolphin safe, for example—but even Izzy is mysteriously silent about the inherently inequitable and classist structure of the homecoming queen election process.

The legend of Brenda Sheldon is suitably spooky and Melissa’s encounter with the ghost lends some credence to the tale, but in the end, much like The Phantom, the violence is driven by grief, as Celeste confesses that Brenda was her aunt. Following Brenda’s tragic death, her family moved away but (for some inexplicable reason) returned to Westdale after Celeste was born, where Celeste was horrified to discover that “No one remembered my mother or that she was Brenda Sheldon’s sister … But worse than that, no one remembered Aunt Brenda. By then, she’d been turned into a horrible legend. It made me so mad!” (198). Celeste is driven by the dual motivations of making others pay for the injustice of forgetting Brenda and claiming the crown for herself, since Celeste has always been told how much she looks like Brenda, how she needs to grow up to be just like Brenda, and “If anyone should be Homecoming queen, it should be me” (198), a bid for the crown that ends horrifically.

While The Phantom and Homecoming Queen each follow their own distinct horror narrative, both address the heartbreaking question of teenage death and its devastating aftermath. Much like the slasher films from which they take so much inspiration, death in ‘90s teen horror novels is sensational and often dismissed without much substantive thought or processing of what it means or the effect it has on those who survive. Reggie Westerman and Brenda Sheldon provide readers an opportunity to reflect upon these questions, including how a lost peer is commemorated and honored, the collective processing of grief, and the loss that sooner or later inevitably becomes a legend.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.