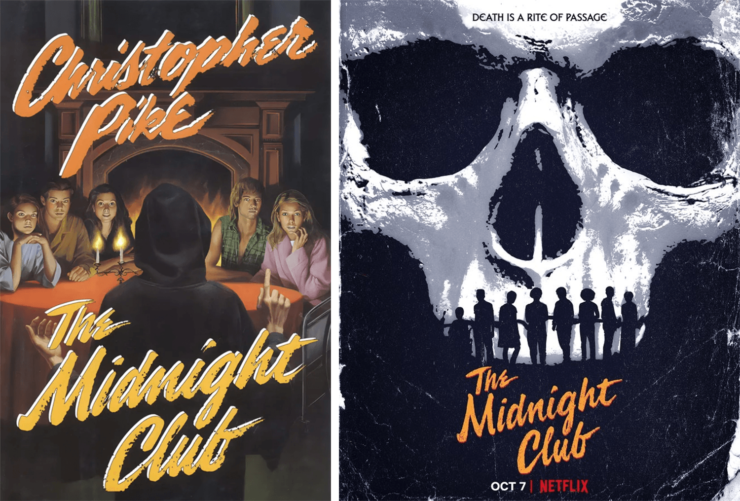

Christopher Pike’s The Midnight Club (1994) was hands-down my favorite of the ‘90s teen horror novels. I don’t remember exactly how many copies of the paperback I went through, but I read and reread it until it fell apart, necessitating at least one trip to the mall Waldenbooks to buy a replacement copy. Even now as I write this, there are multiple copies of The Midnight Club on my bookshelves, including the tattered and well-loved surviving copy from my adolescence.

The Midnight Club is different from the other books of the genre, resonating at its own register. There aren’t any creepy phone calls or madmen on the loose, no supernatural monsters or cosmic terrors. There are just five terminally ill kids in a hospice, who form friendships and tell stories, and know that their time is running out. That awareness and inevitability hold a horror all their own, one that can never be effectively countered or resolved. It is terrifying, heartbreaking, and beautiful, simultaneously too much and never enough.

When it was first announced that Mike Flanagan would be doing a Netflix series based on The Midnight Club, I was thrilled but anxious, flooded with nostalgia but terrified of being disappointed, of not finding the heart and soul of the novel when I watched the series. I also love Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and had been underwhelmed a few years earlier by Flanagan’s Netflix series inspired by that novel, and I worried just a bit about the vision he would bring to The Midnight Club, how that narrative would be shifted and shaped in his version. The combination of recognition and anticipation evoked by that signature Pike font in the title was promising, and I allowed myself some cautious optimism, which proved well founded as I encountered old friends and new horrors, stories both familiar and original, and the context of Pike’s wider world wrapping its arms around it all.

The signature structural and narrative element of Pike’s The Midnight Club are the stories themselves, the tales of horror Ilonka, Anya, Spence, Kevin, and Sandra gather each night to tell one another. Each one plunges the reader completely into another story, taking us away from Rotterham Home (Pike’s name for the hospice) and into another darker, wilder world, from deals with the devil and angels made mortal to shoot-em-up violence and tales of past lives in Egypt and India. Each teller has their own style, their own approach to telling their story. For example, Spence’s stories are “extremely violent” (Pike 44, emphasis original), Anya’s stories thrum with “inevitable horror” (32), and Ilonka’s always focus on past lives, lives she remembers living before this one and usually with some variation of a past-life Kevin by her side.

The Midnight Club series maintains this approach, with each episode’s story-within-the-story drawing on different horror narrative and visual tropes, reflecting the teller as much as the story being told. Natsuki’s (Aya Furukawa) shrieking ghost girl evokes J-horror and her road trip story delves into psychological dreamscape interpretation, while Sandra’s (Annarah Cymone) tale is bursting with noir imagery and dialogue, and Kevin’s (Igby Rigney) blurs elements of serial killer, possession, and haunting narratives. (Beyond the stories themselves, the casting of horror queen Heather Langencamp as Dr. Georgina Stanton is brilliant and opens up a whole separate avenue for engaging with genre traditions, the role of storytelling, and the agency of the teller). As with Pike’s novel, each of these stories take the viewer away from the everyday, from the library and Briarcliffe, from the unforgiving reality with which these teens contend. These stories allow the members of the Midnight Club (with its ranks here expanded to eight members) to temporarily lay down the horrors of their day-to-day existence and their terminal diagnoses and to instead play at being scared, to embrace the cathartic experience of horror as a way of negotiating their own mortality, the meaning of life, death, and what may lay beyond.

Buy the Book

Lost in the Moment and Found

In both Pike’s novel and Flanagan’s series, the stories also give their tellers a way to open up to one another, to share their truths, histories, loves, and fears. Sandra’s story allows her to simultaneously present her beliefs and apologize to Spence (William Chris Sumpter) following their argument about faith and religion. Kevin’s story gives him a chance to express and process his fear about the inevitability of hurting those he loves. Natsuki and Anya’s (Ruth Codd) stories give voice to their past selves, the regrets they have, and the guilt with which they live, stories which are reprised in their more intimate conversations with Amesh (Sauriyan Sapkota) and Ilonka (Iman Benson), respectively. Their stories are not just the tales they tell: in a very literal sense, the stories are who they are.

The collective solidarity of the Midnight Club is also beautifully represented in Flanagan’s series. They are one another’s best friends and families, a role which is particularly significant for those whose families aren’t with them for a wide range of reasons. When Cheri’s (Adia) jet-setting celebrity parents send expensive gifts rather than coming to see her and Spence’s mother (Melice Bell) has rejected him because he’s gay, they are one another’s families. They confess their deepest fears to one another, support one another in sickness and terror, surround one another with love in their final moments, and trust one another to make sure their dying wishes are carried out. Even when they fight with one another, in the depths of their anger and grief, their foundation of love and support remains steadfast. Anya is even more difficult and relentless than she is in Pike’s novel (which is phenomenal!), but her friends are always there for her, whether she wants them to be or not, no matter how unkind she is or how hard she pushes them away. With their shared terminal diagnoses, they understand one another in a way that their peers outside of Brightcliffe never could. This intimacy is echoed in their stories as well, as proxies of their friends and elements of each story begin to filter into those that come later, particularly with Anya’s dream of her life after Brightcliffe and in Ilonka’s final tale, which the others take turns telling and adding to when she is overcome and cannot tell it herself, synthesizing their perspectives and stories.

The continuity of the Midnight Club is a Flanagan addition and one that expands Pike’s narrative, widening the scope of this storytelling tradition. In Pike’s novel, the five members of the Midnight Club are likely the first and only, and when they begin losing members, the group falls apart, leaving the surviving members largely isolated and alone. Flanagan’s Midnight Club teens instead find a ledger, which records the names and stories of the Midnight Clubs who have come before, tracing them back through the history of Brightcliffe. Members leave the circle and new members join, and the stories keep being told. Their invocation emphasizes this continuity as well, as they begin each session with “To those before, to those after. To us now and to those beyond. Seen or unseen, here but not here.” This group is one part of a larger tradition, a bigger story, though that doesn’t diminish their own contributions, instead enveloping them in the camaraderie of others who have sat in their seats, shared their fears and their fates.

Additionally, Flanagan’s The Midnight Club expands beyond Pike’s novel by drawing on a wide range of titles and narratives in Pike’s larger body of work, including Gimme a Kiss (1988), See You Later (1990), Witch (1990), Road to Nowhere (1993), The Eternal Enemy (1993), and The Wicked Heart (1993), which are all titles of Flanagan’s individual Midnight Club episodes. (We won’t dig into the specific narratives of many of these novels here, but what a joy it will be to return to Brightcliffe’s firelit library in future columns when we do!) In addition to invoking specific Pike titles, the stories the Midnight Club members tell in the series evoke Pike’s signature combination of psychological horror and cosmic forces, with time travel, alien beings, and journeys beyond the stars, firmly situating Flanagan’s The Midnight Club within Pike’s creative universe in a way that honors and pays homage to the depth and complexity of Pike’s unique oeuvre.

Flanagan’s The Midnight Club also presents a more progressive and inclusive version of the 1990s, one that serves as a corrective of the whitewashed, straight, middle-class landscape of much of ‘90s teen horror and popular culture. While all of the characters in Pike’s novel are white, the teens of Flanagan’s Midnight Club are a diverse group of adolescents, from a wide range of personal and cultural backgrounds. They have different lived experiences, traditions, and family structures, and while they share these with one another (both the good and the bad), they are not defined by them. The fact that Spence is gay and has AIDS is also introduced early in the series and situated within the context of a larger gay community and conversations about AIDS that are grounded in scientific facts rather than fear, stereotypes, or stigma. This is a significant improvement over the same revelation in Pike’s novel, which comes in the closing pages and Spence’s final days, after he had kept these secrets from his closest friends. When Ilonka invites Spence to tell her his story, he is resistant and filled with internalized shame, telling her that “You can admit to being gay if you’re famous or live in the right part of the country, or even if you’re older. But when you’re a teenager you have to hide it and don’t try to tell me that you don’t” (196). Even as he claims his own voice and tells his own story, he uses self-denigrating homophobic slurs and codes his own desire as an aberration, something “wrong” with him. Ilonka comforts and supports him, affirming his love when she tells him “I’m happy you were able to find someone special” (196) when Spence tells her about Carl, the boy he loved. While Pike’s Spence dies still carrying the weight of this destructive, internalized guilt and shame, in Flanagan’s series, Spence doesn’t hide who he is, he has friends who love him and has been welcomed into a larger community outside of the hospice, and he has spoken his truth to and been reconciled with his mother. All told, I prefer Flangan’s imagined version of the ‘90s, with this inclusivity and acceptance reflecting the way so many of us wish it would have been rather than how it actually was, and it’s lovely to vicariously live in this world, even with its range of attendant horrors.

Flanagan’s The Midnight Club also foregrounds the teens’ relationships with friends and family outside of the hospice more than Pike’s novel does, authentically engaging with the complexity of these connections. Ilonka’s foster father Tim (Matt Biedel) is an excellent and moving example of this, as he struggles with leaving her at Brightcliffe, believing she should be at home surrounded by people who love her rather than in a hospice with strangers. In Pike’s novel, the teens’ families remain largely absent, with the novel focusing on the teens themselves, their relationships and their stories. However, seeing the interactions between Ilonka and Tim, as well as others’ visits during family days, invites viewers to consider the sacrifice families are making when their children come to Brightcliffe, the only place where they can have the semblance of a “normal” life with peers in their final days, rather than being isolated, alone, or languishing in a cheerless, endless succession of hospital rooms. Brightcliffe undeniably offers these teens a much better quality of life in their final days, but the trade-off for their families is that they lose those final days and last moments themselves. There are some exceptions, of course: Anya’s parents are dead, Amesh’s are working to get back to America, Cheri’s may well have dumped her there as a matter of convenience, and Spence’s mother was probably relieved to be able to tell her church friends that he had been sent away. But for many of the terminally ill teens at Brightcliffe – past, present, and future – their families are making a deep and heartfelt sacrifice to bring them there, to give their children’s final days to this place and to one another.

The Paragon and its rituals are a fascinating addition in Flanagan’s series and one that takes Pike’s narrative in a dramatically different direction, while still staying true to many of the thematic elements of ritual and the past in his fiction. In Pike’s The Midnight Club, the teens seem largely resigned to their fate. They are happy to have made friends and they enjoy the stories they tell one another, but generally speaking, they are waiting for death as patiently and passively as they can, forgoing treatment and craving comfort and peace rather than fighting whatever is killing them. Ilonka is an exception, downing all kinds of herbal remedies, eschewing pain killers, and stringently keeping to a clean, all-natural diet in the hopes of regaining her health; she is so certain that the tumors in her abdomen are shrinking that she requests new, additional testing, refusing to acknowledge her increasing levels of pain and exhaustion. Ilonka’s behavior and her steadfast hope are an anomaly, rejected by her doctor and her peers, who aren’t quite sure why she’s bothering, why she’s putting herself through all of this. In Flanagan’s series, this hope is more wide-spread and none of the teens are ready to resign themselves to their fate. They are not giving up or giving in, even when faced with the inevitable. They strive, they live, they fight. Within the context of the teens’ processing of their own mortality and their refusal to submit, the Paragon and its promises are a game changer, asking each to consider not only the prospect of their own death but what lengths they would go to and what they would be willing to do to avoid it. As with the expansion of the Midnight Club itself into a long-running tradition rather than a single, fleeting collective, the Paragon extends the role of Brightcliffe and the negotiation of life and death beyond the narrative of Pike’s novel, maintaining core themes while expanding the scope, and melding the past and the present.

Flanagan’s The Midnight Club was like coming home and discovering entirely new stories, embracing both the familiar and the unexpected. And most importantly (for me, at least) the heart of Pike’s novel was still there and if anything, had been deepened and enriched by the addition of more stories, the further development of familiar characters, and the addition of wonderful new ones. The addition of the Paragon foregrounds a meditation on how humanity as a whole and our individual cultures grapple with the mysteries of life and death, while the Midnight Club members themselves keep that consideration firmly grounded in the individual, the intimate, and the human, a consideration which is simultaneously existential and deeply personal. And while the final scenes (Ilonka and Kevin’s kiss, Stanton’s wig and tattoo) address some loose ends and offer some suggestion of what may happen next, I for one would have been entirely content to fade out in the library with the fire burning, surrounded by friends, waiting for the next story.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.