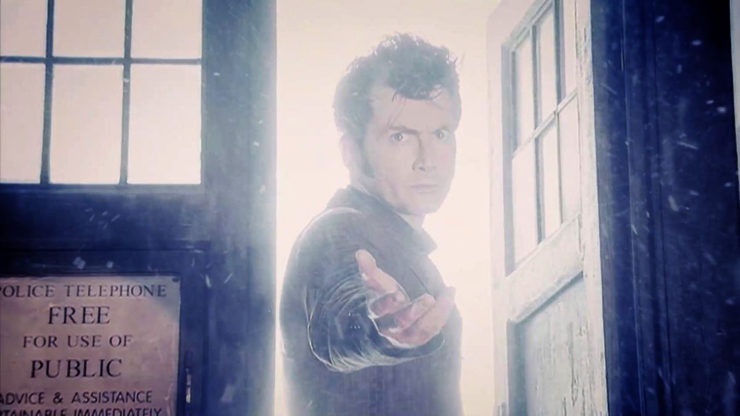

“Ha! You think this is Hell.”

–Doctor Who, “The God Complex”

If the Doctor showed up in your living room and offered you a lift in the TARDIS, would you go with her (or him, depending on which regeneration you encountered)? Leave everything behind for a chance to explore the past, the future, the distant galaxies of the universe?

I will go ahead and assume that at this point many of you are screaming “yes.” That certainly was my reaction to that question when I was introduced to the show (with Christopher Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor, I’m afraid; being quite American, I wasn’t exposed to the classic show until later). A chance to find out all the secrets of the universe, with bonus adventuring? Sign me right up! But that same month that I first began watching Doctor Who, I read about another Doctor: Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (this is one of the perils of an English degree). And looking back on them both, I can’t help but notice some alarming similarities between what the Doctors offer their companions and what Faustus bargains for from the devil, and between the surprising difficulties both Faustus and those companions encounter in actually getting what they’re promised. And that all makes me wonder if maybe what the Doctor has on offer is quite so attractive after all…

Now, I’m not suggesting that the Doctor is the devil incarnate, or even evil (that would be a very different, and longer, essay). But even before we get to the promises they make and the limits of those promises, it should be notes that the Doctor has some other major similarities to Faustus’ devil, Mephistopheles. First, like Mephistopheles, the Doctor can look different at different times. The very first thing Faustus tells Mephistopheles to do is “change thy shape”—and he does it, changing from whatever-it-was he looked like first into a Franciscan friar. The Doctor may not have as much control as that (after all, over several regenerations he was “still not ginger!”) but regeneration is a core element of the show, and that changeability is a defining feature of Time Lords, as apparently it is for Faustus’ devils.

Second, the Doctor and Mephistopheles are both deeply haunted by the past, but refuse to talk about it. Mephistopheles tells Faustus he is always in hell, no matter where he goes, but won’t say anything about what heaven was like. Like the war in heaven, the memory of the Time War lies heavily on the Doctor, especially in the early years of NuWho, and he snaps at anyone who wants to know about it.

Finally, as River Song can testify, the Doctor can and does tell some of his companions exactly when they’re going to die. And interestingly enough, when the Doctor gives River a last night that lasts twenty-four years in “The Husbands of River Song,” that is exactly the same length as the contract that Faustus seals with Mephistopheles: the demon will serve him for “four and twenty years,” after which he will be dragged away to eternal torment.

Likewise, we see both abuse their power. Setting aside large questions of morality for each (damnation of souls, Dalek genocide), both characters can be quite petty. Mephistopheles has Faustus eat the Pope’s dinner while invisible, then punch the pontiff and mock Christianity. The Doctor rarely wades into religious issues, but also isn’t beyond arbitrarily punishing humans who bother him. I think in particular of Harriet Jones, Prime Minister (you know who she is—or if you don’t, here’s a refresher). The Doctor doesn’t give her a box on the ears, but he does destabilize her government after she crosses him, just as Faustus and Mephistopheles do their best to weaken the papacy.

Buy the Book

Lost in the Moment and Found

On a less geopolitical note, we might consider how rejected companion Adam Mitchell feels in “The Long Game” when the Doctor dumps him back on Earth with an easily-opened hole in his head and compare it to the kind of targeted embarrassment that Faustus and Mephistopheles get up to with the Knight, upon whose head Faustus conjures a pair of horns, or the horse-courser to whom they sell a horse made of straw. Like Mephistopheles, the Doctor has an awful lot of power and doesn’t always use it for good (though to be fair, he does more good than the devil).

But let us move beyond the Doctor and the devil to the humans they deal with and what those humans desire. Faustus shares a motivation with many of the Doctor’s companions. He makes his bargain by offering his soul in exchange for knowledge, and specifically, knowledge of the world and what lies beyond it: “all characters and planets of the heavens,” what he calls “divine astrology.” What else is this but the power to travel through space, to visit distant planets and galaxies, as in the TARDIS? And before you point out that the TARDIS is a time machine too, Faustus also shows a real interest in the past. He conjures up Alexander the Great and Helen of Troy, even kissing Helen. But just as the First Doctor insists that “you can’t rewrite history, not one line” (at least not without unleashing Reapers, as Rose finds out in “Father’s Day”), Mephistopheles proves only capable of providing spirits that imitate those historical figures. In both cases the power associated with the knowledge of the past is more limited than it first seems.

Moreover, both the Doctor and Mephistopheles avoid answering questions they don’t like–and not just personal ones. The Doctor never really helps to advance human technology on Earth to be equal to that of the invaders from the stars, even when he serves as a science advisor to UNIT during his long exile on Earth as the Second and Third Doctors. And he is not pleased to find out in The Christmas Invasion that Torchwood has been doing its best to scavenge alien tech and rehabilitate it on its own. The go-to explanatory terms in the show are no explanation at all, like “wibbley-wobbley” and “timey-wimey” (this is obviously partly to avoid dating the show from current knowledge, but it still feels a bit dodgy). Mephistopheles is equally coy about the deeper questions Faustus asks: he answers a then-vital question about eclipses and other movements of the stars by just saying that the difference comes from unequal motion against the whole, which is no explanation at all. It’s the kind of answer-adjacent non-answer of which the Doctor could be proud.

Now, there is one very obvious difference here: the companions are not destined to be dragged away to hell to be ripped apart at the end of their time with the Doctor, as Faustus is, and thank goodness for that! But they are hardly immune to devastating consequences, from Rose being thrown into an alternate universe and Clara Oswald diving into the Doctor’s own timeline to be shattered into millions of pieces and dispersed, splinter-like, throughout his life to River Song’s own self-sacrifice in the Library. Like commanding Mephistopheles, traveling with the Doctor has a high mortality rate unless you make the choice to leave voluntarily (as Faustus proves unable to do). Though to be fair, the Doctor is certainly less enthusiastic about this than Mephistopheles is about Faustus’s doom.

None of this necessarily means that the Doctor’s bargain isn’t worth taking, or that the Doctor’s relationship to the companions is the same as Mephistopheles’s to Faustus. But I do believe that thinking about Faustus—“regard[ing] his fall,” as the play has it—means that if a charismatic stranger shows up and offers you the adventure and knowledge you’ve always been waiting for, you should think long and hard about exactly what you might be getting out of it, and exactly what it might cost.

Philip Styrt is an academic who writes and teaches about early British literature, writing, and speculative fiction. If you want to tell him why your Doctor in particular isn’t the Devil, you can find him on twitter @pstyrt.