Perhaps one of my favorite aspects of reading The Wheel of Time is how often I find myself in characters when I’m not expecting to. I am accustomed to seeing my weird self reflected in robots and fairies, aliens and outcast knights, because these categories are often used as analogies for othered and marginalized people—and I belong to a few of those groups. When it comes to Robert Jordan’s work, however (and I realize that I am generalizing here), his characters feel a bit more literary than genre to me, despite their setting and the magical things that they can do. As a result, I don’t look for the tropes the way I might in other fantasy works, and moments of connection sneak up on me in different ways.

A few weeks ago while reading Chapter 49 of Lord of Chaos, a specific moment for Rand struck me, and it really changed how I felt about an entire aspect of his journey.

Lews Therin has been steadily solidifying as a presence in Rand’s mind, so much so that he’s tried to argue a few times about whose body it is, and has even tried several times to seize saidin. Rand has had to devote a significant amount of energy to restraining himself from reaching for it, lest Lews Therin take control. Then, when Min reports to Rand that there are now thirteen Aes Sedai in Caemlyn, Lews Therin fully panics.

Buy the Book

The Eye of the World: Book One of The Wheel of Time

“Thirteen,” Rand said flatly, and just saying it was enough for Lews Therin to try seizing control of saidin from him again. It was a wordless struggle with a snarling beast. When Min first said there actually were thirteen Aes Sedai in Caemlyn, Rand had barely managed to seize the Power before Lews Therin could. Sweat rolled down Rand’s face; there were dark patches on his coat. He only had room for concentrating on one thing. Keeping saidin away from Lews Therin. A muscle in his cheek jumped from the strain. His right hand trembled.

This is an invisible battle for Rand—no one knows that Lews Therin is his head, nevermind that he might possibly be able to affect or control Rand’s actions. When Rand later collapses from the effort of fighting Lews Therin for so long and has to be carried to bed, nobody knows what has really happened to him.

Taint madness isn’t really analogous to real world mental health issues. The symptoms—anger, violence, destruction, and an inability to recognize reality—are associated with certain presentations of psychosis, but there is not enough detail in the description of what happened to Lews Therin and the Hundred Companions to elevate their insanity past the general stereotype of how popular culture depicts most types of mental disorders and neurodivergent conditions. But in Rand’s experiences we have much more specificity, and it is here that many people with mental illness or disabilities can actually find a lot of things that they may relate to.

Take, for example, the stigma around the taint. The very fact that he has been touched by the Dark One in this way means that everyone is always anxious around Rand. The taint only directly affects those who reach through it to wield the male half of the One Power, but when Egwene realizes that Rand has made her invisible by wrapping her in flows of saidin she is alarmed and unsettled—she feels as though, should the weave touch her at all, the taint will as well. As a channeler herself, Egwene knows that there is a difference between physical touch and metaphysical touch, but the anxiety is still there.

The moment was a stark reminder for me of how Rand’s friends treated him when they first learned that he had the ability to channel. It wasn’t just the knowledge that he would eventually become dangerous to others that caused everyone to keep their distance and made Mat openly hostile. It was the awareness that the taint, the corruption of the Dark One himself, would be lingering around Rand before he showed any symptoms of it. Even men who have been gentled, who can no longer touch saidin or the taint, are ostracized and vilified by others for this perceived corruption, as we saw with Thom’s nephew Owyn.

In our world, the stigma around mental illness often includes a fear of contamination. Mental disorders can sometimes have a genetic component, but they aren’t contagious, and yet people with these conditions are often shunned as though their tics and other symptoms might be catching. We often ascribe a moral component to mental illness as well—there are many who believe that the person must have done something to deserve their condition. That they must be bad, or lazy, or unclean. We even stigmatize neurodiversity as being something inherently bad—yet while many aspects of neurodivergent conditions do cause distress for those who have them, many are not “bad” or undesirable so much as they are different and unaccommodated.

Rand experienced a lot of pain when he first started being shunned this way, and it’s the first real consequence he experienced upon learning of his true identity. I feel this pain very acutely, relating to it not only as someone who is neurodivergent but also as a queer person. Of course, queerness isn’t a mental illness, but many people believe it to be, and queerphobes often express a fear of being exposed to queerness lest they “catch” transness or are somehow “turned” gay. They punish queer people for this, yet someone’s sexual and gender identities don’t have anything to do with anyone else’s. Just as the taint touching Rand when he channels has nothing to do with those who cannot wield saidin.

I also suffer from anxiety, which sometimes does feel like another person in my head. This person whispers bad advice into my mind, sees problems where there are none, and loves to encourage me to preempt the threats it sees all around me. My anxiety person mostly urges avoidance, but it’s not that big a leap to imagine it taking a different tack and urging a strike instead. Lews Therin might not be real, at least in any conventional sense of the word, but anxieties come from a real place—he sees betrayal in Taim because he was betrayed by his allies, he fears larger numbers of female Aes Sedai because he know that their ability to link means that they can overpower him if they choose. Lews Therin is a war veteran, and his PTSD is showing. And while I don’t have PTSD, I do have trauma in my life, and I know how it can warp your perspective and dominate your thinking.

But Rand’s collapse reminded me most of all of my experience of depression. Depression is exhausting, and though it feels less like a person for me than anxiety does, it is the thing that I feel like I am fighting an invisible battle against. Depression makes it difficult to do anything, to feel motivated, to see possibilities, to see a point to things. On a bad depression day, the basic acts of life—work, errands, cooking dinner, even brushing your teeth—seem like herculean tasks. All your energy throughout the day is sapped away as you hold the symptoms of depression at bay, and I have definitely had moments like the one Rand had at the end of Chapter 49. I know what it’s like to collapse, exhausted, at the end of the day, even though an outside observer would see little evidence of what tired me out so much.

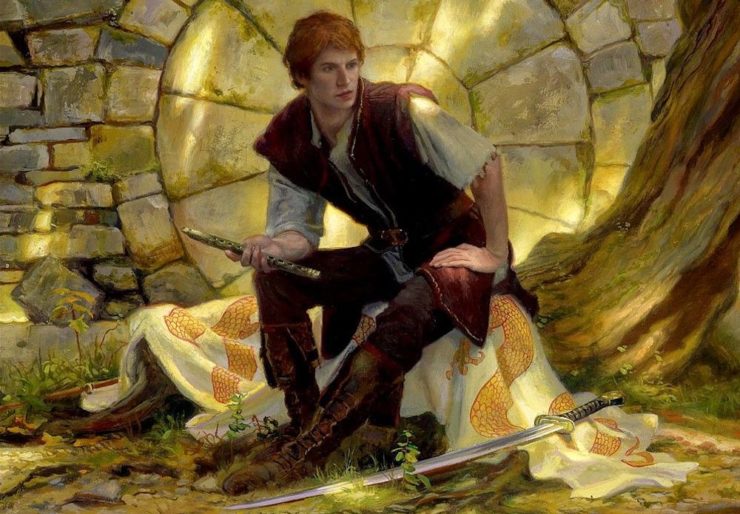

It is only after reading this moment that I recontextualized the other instances where we saw Rand struggle with Lews Therin. But suddenly this extreme, fantastical version of mental illness seemed so much more approachable, so much more relatable. Even Lews Therin’s experience did, when I went back and reread the Prologue of The Eye of the World. In it, we meet a Lews Therin who is still under the influence of what the taint has done to his mind, but who is no longer experiencing violence or anger. The taint’s effects now seem to be a dissociation from reality and sudden mirth—a fairly standard and generic picture of “madness” in pop culture. There is a moment, however, after Elan Morin arrives, where some part of Lews Therin seems to have a moment of lucidity.

“Betrayer of Hope.” It was a whisper from Lews Therin. Memory stirred, but he turned his head, shying away from it.

This moment, in contrast with the other symptoms Lews Therin displays, is almost an afterthought, and I found myself wondering if this was the madness of the taint, or a moment where Lews Therin’s own mind deliberately avoided recognizing the truth in front of him. Because this is a real and common reaction to trauma—denial and dissociation are methods the brain employs to protect us, which can be useful in certain short-lived circumstances. Rereading, I found that I related to that moment, found that I was remembering times in my own life when I avoided seeing a painful truth. I often judge myself for those moments of denial, but I found grace for myself, and for Lews Therin, as his mind shied away from a truth that would ultimately, when faced, lead to his suicide. Having experienced suicide ideation in my own past, I felt a sort of camaraderie with Lews Therin and with Rand, despite the fact that their specific trauma is exaggerated and fantastical in nature.

Ultimately, the taint is Evil-capital-E, as it comes from the Dark One himself, which can make it a poor metaphor for real-world mental health issues, just as Balthamel’s reincarnation as Aran’gar is no metaphor for being transgender. However, much of what Rand experiences as his mind is corrupted by the taint is relatable to those who have experienced symptoms—and stigmas—of mental illness and disability. This particular one has affected me in a profound way.

As a longtime fan of epic fantasy, Sylas K Barrett is always happy to discover new ways of experiencing and relating to fantastical, otherworldly characters.