In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The world, and indeed the wider universe of our imagination, can be a frightening place. And among the most horrible places, real or fictional, is the battlefield. The very real horrors of war dwarf even the most terrible of fantastic monsters, even the uncaring and powerful Cthulhu. And one of the science fiction authors most adept at capturing those horrors effectively is David Drake.

One outcome of a draft is that you get people from all walks of life entering the military. This includes literary people, whose military experience goes on to shape their writing. The bloody and inconclusive Vietnam War had a huge impact on the writing of David Drake, who served in the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment in Vietnam and Cambodia. His experience gave his writing a visceral urgency, and some accused him of glorifying war. But I would suggest that readers look at his stories from a different perspective, that of a horror story.

About the Author

David Drake (born 1945) is an American writer of science fiction and fantasy, whose career started in the 1970s and ended with an announcement in November 2021 that he was retiring from writing novels due to health issues. Drake’s work was often rooted in his deep knowledge of history and legend, working with the elements and material of old stories in new and different ways. I’m sure his many fans are disappointed his career has come to close.

I’ve looked at David Drake’s work before in this column, reviewing his book The Forlorn Hope, and also The Forge, his first collaboration with S.M. Stirling in the General series. Those reviews feature some biographical information that mostly focused on the Hammer’s Slammers series. That series included quite a bit of material, about seven books worth of short stories, novelettes, and novels, which were later repackaged in a variety of ways, most recently in a three-volume omnibus edition. There are also related novels set in the same or a similar universe.

But while the “Hammerverse” is perhaps Drake’s best-known series, his substantial body of work extends beyond those stories, and is not limited to army-centric military science fiction. He’s written nearly as much fantasy as science fiction. His longest fantasy series is the nine-book Lord of the Isles sequence. The longest of all his series is the thirteen-book Republic of Cinnabar Navy series, started later in his career, which was inspired by Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin Napoleonic-era naval adventures. Because of Drake’s popularity, he was also much in demand as an editor for anthologies and as a senior co-author for many projects. Several of Drake’s books are available to download free of charge from the Baen Books Free Library.

Horror Fiction

When I was first struck by the idea that Hammer’s Slammers is a horror story, I immediately had to do some research. I am not a person who reads horror fiction, and other than a few Stephen King and Neil Gaiman stories, have little experience with the genre. Two resources I immediately found useful were a basic search for horror fiction on Wikipedia article and an article in the Encyclopedia of Science fiction on “Horror in SF,” and I encourage interested readers to follow those links, as they address the larger topic far better than I could.

Buy the Book

The Book Eaters

The Wikipedia article immediately quotes J. A. Cuddon, a literary historian who defines horror fiction as something “which shocks, or even frightens the reader, or perhaps induces a feeling of repulsion or loathing.” The article takes us on a trip through the history of horror fiction, starting in the days of legend and bringing us to the literature of the present day and authors like Stephen King. I found a quote from King on Goodreads identifying three different means of inducing visceral feelings in the reader. The first is the “Gross-out,” something like a severed head, which creates a feeling of revulsion. The second is “Horror,” unnatural and threatening creatures or situations. The third is “Terror,” which is a feeling that something is wrong, and unseen threats are lurking.

Sometimes horror fiction uses the supernatural to scare the reader, invoking zombies, monsters, ghosts, demons, vampires, and other creatures that do not exist in the real world. Other types of horror fiction rely on terrors that exist in the real world, focusing on serial killers and other criminals who commit heinous crimes. And it is here I think many war stories fit. We’re all familiar with war stories that are not rooted in horror, but instead consider the glorious aspects of war; these stories focus on bravery, strategic maneuvers, adventure, derring-do and triumph on the battlefield, and often leave the hero better for their military experience, marked perhaps only by a tasteful dueling scar on their cheek. That, however, is not the tale David Drake wanted to tell.

He came back from war scarred by what he had lived through, and wanted to show people what combat was really like. And what he portrayed in his fiction certainly fit Stephen King’s categories of the Gross-out, Horror, and Terror. The gross-out elements come from the brutality of close combat, and the way the weapons tear apart human flesh. The horror is especially clear during the impersonal mayhem of artillery barrages, and in the helplessness experienced in situations the combatants cannot control. And the terror arises from constantly being on edge, never sure when the next attack will come, or who you can trust. Reading Hammer’s Slammers again, decades after the first time, I became more and more taken with the idea that while this is a war story, it also could be read as a horror story with military trappings.

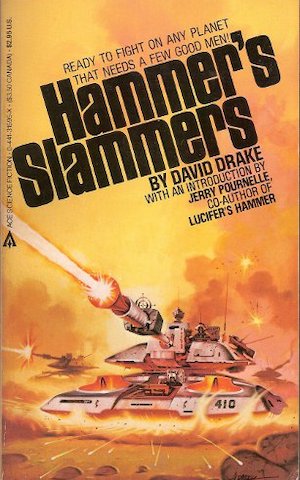

Hammer’s Slammers

The book—which is not a novel, but rather a collection of shorter works—opens with an introduction from Jerry Pournelle entitled “Mercenaries and Military Virtues.” I am not surprised Pournelle focused on military virtues, as he often did in his writing. But I think he missed the mark on this introduction, as Drake is far more concerned with showing us the horrors of war over any virtues that might be found in its pursuit. Each of the stories has its own moral, usually of a grim nature. The lessons participants take away from combat are often not positive ones.

The first story, “But Loyal to His Own,” portrays the origin of Hammer’s Slammers, a unit organized by Secretary Tromp, the ruthless Secretary to the Council of State of the Planet Friesland, with the aim of crushing a rebellion. He turned a blind eye to the brutality of the unit during the action, and now wants to disarm them. And instead of giving promised citizenship to its members, he seems to be considering having them executed. Colonel Hammer suggests instead hiring the unit out as mercenaries, but Tromp does not want to upset the interstellar status quo with such a plan. Rather than accept this betrayal, the Slammers swing into action and cut through the other troops like a hot knife through butter. One of Hammer’s most fearsome officers is Major Joachim Steuben, his aide, who is more bodyguard and assassin than anything else. (Unusual for books written in that era, Steuben is also openly gay.) At Steuben’s hands, Tromp reaps the whirlwind he has unleashed. And when they escape Friesland, Hammer’s Slammers become a mercenary unit after all. The depressing moral of this story is that you cannot trust anyone outside the unit.

Between each story in the collection there are expository articles called “Interludes,” that give information on the technology used in the series. Separating these out from the stories prevents the background from bogging down the narrative, and while they can be skipped, they are placed in an order that often illuminates some point in the stories that surround them. The first of these, “Supertanks,” explained how technology led to Hammer’s era being one where armored behemoths rule the battlefield. Powerful fusion powerplants allow treads to be replaced with hovercraft technology, and permit carrying heavy armor plating. Active defense measures, networked fire control, and advanced sensors also protect the vehicles from a variety of threats. And the heavy plasma-firing main guns give the tanks the power to destroy anything within line of sight.

“The Butcher’s Bill” is told from the perspective of one of the tank commanders, Danny Prichard. He has become romantically involved with one of the local officials who provides liaison with the unit, something that his Colonel has encouraged. She shows him buildings left on the planet by an alien race, ancient and irreplaceable. But the enemy tries to use areas around these structures as a base to discourage attacks. The Slammers attack anyway, and in destroying the enemy, destroy the archaeological treasures. The moral here is that you can’t let anything stand in the way of completing the mission.

The next interlude, “The Church of the Lord’s Universe,” shows how religious fervor helped fuel the spread of humanity into the stars. It also gives insight into some of the phrases the Slammers use as curses.

“Under the Hammer” is told from the perspective of raw recruit Rob Jenne. He is being transported to his new unit in a shorthanded command car when it comes under attack. Jenne has absolutely no training other than a cursory introduction to his sidearm and pintle-mounted gun on the car, but is thrown into the middle of a bloody firefight that ends up in a heavy artillery barrage. The lesson that war is horrible is amplified by Jenne’s inexperience, and the sense of hopelessness he feels with death all around him.

The interlude “Powerguns” then offers insight into the main weapon used by the unit. Powerguns fire pulses of copper heated to a plasma state, projected with such energy that they are line-of-sight weapons. They range in size from handguns to the main guns of the tanks, and are far more destructive than ordinary projectile-firing weapons, having an especially horrible impact on an unarmored person.

The next story, “Cultural Conflict,” is a pure horror tale from beginning to end. The Slammers are being pulled off a planet, but before they can leave, a trigger-happy trooper in a small artillery unit shoots an ape-like indigenous creature. His officer, who he does not respect, had ordered him not to fire at anything, but the trooper ignores the order…and learns that even bad officers can sometimes be right. The death triggers an overwhelming response from the indigenous creatures, whose society is collective and ant-like. The Slammers react to that response with even more force. Both sides are drawn into a bloody conflagration that results in genocide and massacre. Communication and restraint could have prevented the tragedy, but it is hard to rein in troopers who have been in combat and are constantly on edge. This is a horror story where both sides become monsters, and I can’t think of a clear moral, other than the nihilistic message that life is meaningless.

The interlude “Backdrop to Chaos” is an excerpt from a history book that explains that the system of mercenary warfare that the Slammers were part of was not sustainable, and only lasted for a short time.

The tale “Caught in the Crossfire” introduces another new character, Margritte, whose husband is murdered by mercenaries who are setting up to ambush the Slammers. Margritte enrages the other women in the village by cozying up to the murderers, only to use their trust to ambush the would-be ambushers. When the Slammers roll through, realizing the other women will never trust her again, Margritte volunteers to leave with the unit. The hard moral here is that the people you save often do not appreciate your efforts.

“The Bonding Authority” interlude explains the legal structure that controls the actions of mercenary units, and shows how failure to comply can lead to severe penalties and even disbanding of the organizations.

In “Hangman,” Danny Pritchard is now a Captain. Margritte from the previous tale is now his radio operator, and Rob Jenne his chief. (And there is also a female infantry commander, Lieutenant Schilling. Drake was notable during this era for depicting women in combat roles, something that was not at the time permitted by the U.S. military, and even its fictional portrayal was fiercely resisted by many science fiction authors.) A rival mercenary unit is stretching the rules of mercenary warfare, and so are certain elements within the Slammers. Danny must risk everything, working behind the scenes with Colonel Hammer, to prevail while staying within the constraints of the bonding authority. Prichard and his crew face fierce combat, reversals of fortune, acts of brutality, betrayal, death, and devastating injuries before the gripping story is over, and Prichard realizes that, to accomplish his mission, he has become an executioner, a hangman. The moral is that even in victory, there is no glory in war.

The interlude “Table of Organization and Equipment, Hammer’s Regiment” shows us the composition of the Slammers in the form of a TOE that will be familiar to anyone who has experience with the Army or Marines.

Unusually for a collection of short stories, the collection also features a tale, “Standing Down,” about the end of the Slammers as a mercenary organization, bringing the book to a satisfying conclusion. The Slammers have been hired to support a revolution on their home planet of Friesland; with the death of the revolutionary leader, Hammer takes over and becomes president, entering into a political marriage to a ruthless and unattractive woman from an influential family. The Bonding Authority representative is sure that, because the Slammers were so far away from the revolutionary leader when he died, that they couldn’t have been involved with his death. He is not, however, familiar with the marksmanship of Major Steuben…

But Hammer is off his game, and not at all comfortable with the role he has attained. He summons Danny Prichard, but Prichard, who is now in a relationship with Margritte, is in civilian clothes and wants nothing to do with the military ever again. What Hammer needs most, though, is someone he can trust with abilities in civil affairs, and he offers Prichard a role in his new government. The moral here, as we watch the normally unflappable Hammer struggle with his new life and responsibilities, is to be careful what you wish for, because you might get it.

Final Thoughts

Drake is a skilled writer, and Hammer’s Slammers is a powerful book that makes the reader feel like they have been in the center of the action. The book is remarkably cohesive for a collection of shorter works, and packs a considerable emotional punch. It does not shy away from dwelling on the horrors of war, and indeed puts horror front and center. It is also a book that makes you think, and should discourage anyone from ever considering war to be a neat and tidy solution to diplomatic issues.

And now I’d like to hear your thoughts: If you’ve read the book, would you agree with my assessment that it can be considered a horror story?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.