Welcome to Close Reads! In this series, Leah Schnelbach and guest authors dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, Tobias Carroll asks if Marvel’s No-Prize will be humanity’s downfall.

Every few months, like clockwork, I’ll look at what’s trending on Twitter and see people debating whether or not Marvel’s television shows that predated Disney+ are canonical. It is an endless debate and I hate it, and I also hate both the fact that I hate it and the fact that I care enough to hate it. Reading an argument about how Mahershala Ali being cast as Blade means that Luke Cage is definitely out of continuity, or what the bit with the watch at the end of Hawkeye means for Agents of SHIELD, gives me a migraine—sometimes figuratively and sometimes literally.

This is a frustration that goes far beyond the hate-click economy, though. My frustration kicks in because of its implications for reading and watching things—that kind of uncanny projection that happens when everyone is now an expert in the continuities of various storylines. What it makes me think of, above all else, is that the Marvel Comics No-Prize is somehow responsible for this entire state of affairs.

Maybe you’re nodding along, or maybe you’re bewildered right now. Let me explain.

The No-Prize began as a way for Marvel to reward readers who noticed inconsistencies or typos in their comics. Over time, as Brian Cronin points out in his history of the No-Prize, grounds for receiving one—sometimes in the form of an empty envelope—involved noticing seeming inconsistencies in certain comics, and then coming up with a viable reason for why they weren’t inconsistent at all.

This system was in place by the mid-1980s, though the grounds for receiving a No-Prize varied from editor to editor. Cronin’s history includes two succinct descriptions of the No-Prize from editors Christopher Priest (“We only mail them out to people who send us the best possible explanations for important mistakes.”) and Ann Nocenti (“The spirit of the no-prize is not just to complain and nitpick but to offer an exciting solution.”).

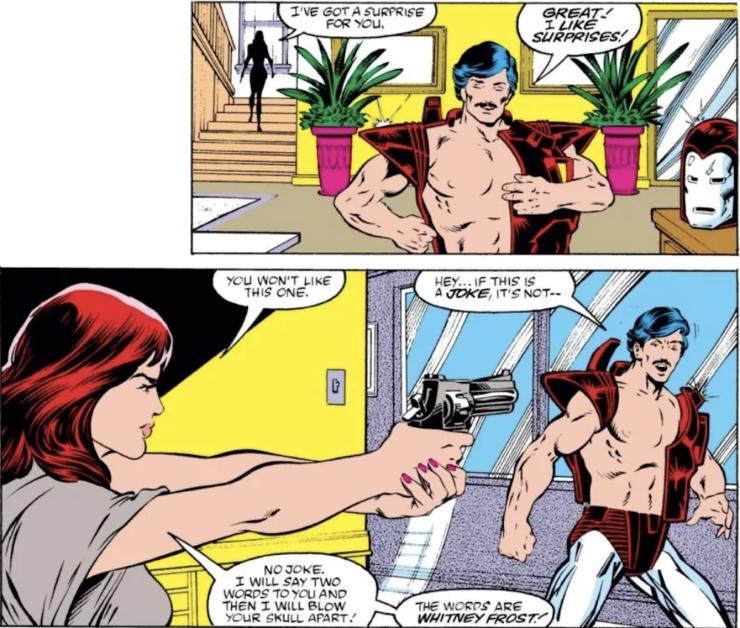

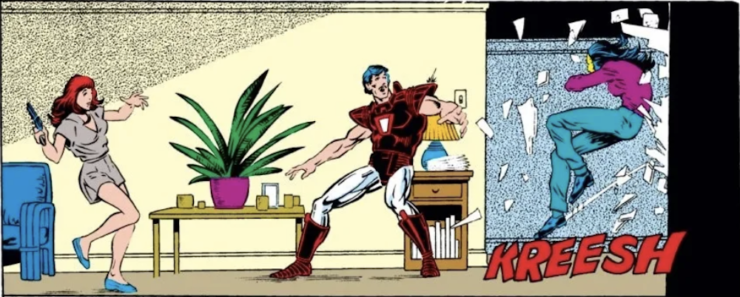

Cronin’s overview cites one example of a No-Prize-winning theory: in Iron Man #203, Tony Stark’s armor goes from seemingly being open to covering his chest in the span of two panels where he’s threatened by an enemy with a gun. Crouton Jim Chapman wrote in to theorize that Stark noticed the threat and “activated the holographic projector in his suit to make his chest appear to be unprotected.” Chapman ended up winning a No-Prize for his trouble.

It’s probably worth noting here that the No-Prize has gone through several permutations over the decades, and something that won a No-Prize at one point in time might not have qualified for it at another. But this particular iteration lines up with my most intense period of reading superhero comics in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It’s also telling that Priest and Nocenti, cited above, edited the Spider-Man and X-Men lines of comics, respectively—which was where the bulk of my Marvel reading took place back then. I will also confess that I did my fair share of looking through issues for continuity errors so that I might win a No-Prize of my own, something which never quite worked out for me. But the biggest thing I took away from the No-Prize was the notion that someone might end up knowing the ins and outs of a story better than its author.

Death of the author theorizing aside, this isn’t exactly a controversial concept. In a 2017 interview, Robin Furth described her work for Stephen King as it pertained to the Dark Tower series as “[making] lists of characters and places so [King] could check the continuity of events.” And Elio M. García Jr. and Linda Antonsson founded the A Song of Ice and Fire community Westeros.org, and subsequently went on to collaborate with George R.R. Martin on the book The World of Ice and Fire. (It’s probably worth mentioning here that Martin’s early comics fandom is also inexorably connected with the history of the No-Prize. Time is a flat circle—one which Galactus is going to devour any minute now.)

Looking back on the No-Prize as it was in my formative years, I’m left with two conflicting conclusions. The first is that it encouraged a generation of readers to think like storytellers, which is an unabashedly good thing in my book. If you’re examining something and trying to find a solution for what appears to be an error within the internal boundaries of that narrative, that’s one way to get a foothold into telling compelling and internally consistent stories. They aren’t necessarily your stories, but it’s not hard to see where the step to that next level could emerge.

The second conclusion is a little more bleak. It’s that you can also find the inclination to stop looking at a narrative as a story and beginning to see it as a series of problems to be solved in the legacy of the No-Prize. (This, in turn, seems a close cousin to the school of criticism that involves boiling a work down to the tropes it contains.) Some of that is a matter of degree, of course.

To return to the example cited earlier, if someone looks at an Iron Man comic and comes up with a solution to a seeming inconsistency in the art, that process holds the potential of actually expanding the comic’s storyline—of adding an action that the creators may never have intended, but which is nonetheless in keeping with the themes of the book. (In this case, the idea that Tony Stark is resourceful and knows how to think on his feet.) It feels like a slightly more formalized headcanon, and it could lead to revelatory places.

But the idea of reading or watching something nominally for pleasure with the primary goal of finding errors and inconsistencies sounds like the furthest possible thing from pleasure one could imagine. Perhaps it’s for the best that the No-Prize moved on to honoring other things. We’re living in the pop culture world it made, for good or for ill.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).