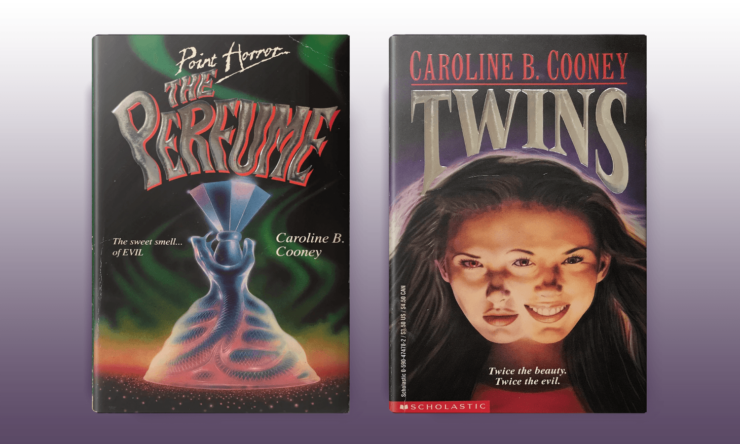

In ‘90s teen horror, there are a lot of burning questions about mistaken identity and subterfuge, leaving characters often wondering who they can trust and whether their new friends are who they claim to be. In The Perfume (1992) and Twins (1994), Caroline B. Cooney takes this question of identity and reality one step further, as Dove and Mary Lee must face their respective twins and deal with the consequences of their actions. In The Perfume, Dove’s twin is internalized, a presence in her mind that takes over her body, while in Twins, Mary Lee has an actual identical twin named Madrigal, but while the nature of the girls’ twins differ, the themes of identity, self, and perception resonate between the two novels.

In The Perfume, Dove spends much of the novel trying to decipher the nature of her new internal twin. Dove thinks of this emerging presence as her sister, a twin who was absorbed in the womb. As her parents tell her, they were expecting twins and had names picked out: “One daughter would be Dove … Soft and gentle and cooing with affection,” while the other would be “Wing … Beating free and flying strong” (29). Their chosen names provide a stark demarcation of personality traits and attributes, and when they find themselves with one daughter instead of two, they privilege gentle femininity over strength. Dove has a different perspective on the names and she is horrified as she reflects that “A Dove was whole. A complete bird, a complete child. Whereas a Wing – that was just a portion. A limb, so to speak, wrenched off, and lost forever” (29), a more corporeal and violent division of these two identities. But there’s also the possibility that Dove is possessed by an ancient Egyptian spirit, which takes up residence in Dove’s body through the scent trigger of a new perfume called Venom. Egyptian imagery and allusions abound in The Perfume, from history class discussions to the glass pyramid that tops the mall where Dove and her friends like to hang out, and Dove internalizes this historical connection, wondering if “the inside of her head [was] a sort of round pyramid? The tomb in which this other creature had been kept for fifteen years” (33). The store where Dove bought the perfume mysteriously disappears after she buys it, which lends a potentially supernatural vibe to the series of events, though Cooney also offers more prosaic explanations and interpretations as well, including teenage rebellion and identity experimentation, or the possibility of a brain tumor or mental illness.

When Wing takes control, Dove is shunted aside within her own body, watching in horror as Wing attempts to hurt her friends. Wing is the anti-Dove: violent and uncaring, looking for any opportunity to hurt or even kill others, as she contemplates pushing a boy out a hot air balloon or grabbing her friend’s steering wheel to force a car accident. Dove argues with Wing and tries to curb her destructive impulses, with this internal struggle externalized as the two identities carry on these negotiations aloud. This means that Dove’s friends know all about the horrible things that Wing says about them and how much she wants to hurt them, which is off-putting to say the least. Control of Dove’s body shifts back and forth between Dove and Wing over the course of the novel, usually initiated by scent triggers—Venom to awaken Wing and softer floral scents to draw Dove back—though since Wing is an internalized and disembodied presence, Dove has to shoulder the consequences of their actions on her own.

Buy the Book

Just Like Home

In the end, Dove is able to reclaim control of her body and the sovereignty of her identity through sheer force of will, following her realization that “Fighting evil cannot be easy. It can’t be accomplished by lying there. Nor by wishing. Nor by feeling sorry for herself. She had to get up and fight” (159). Dove climbs into the mall fountain beneath the giant glass pyramid and expels Wing from her body, and while Wing puts up a good fight, she ultimately finds herself freed and fading.

One hallmark of Cooney’s novels is that in spite of the outrageous and supernatural horrors with which her characters often contend, they remain firmly grounded in the real world, with real consequences. When Dove’s behavior becomes dangerous to herself and others, she receives psychiatric treatment and is briefly hospitalized. This is an isolating and objectifying experience for Dove, as the doctors see her as a subject, a “case” (140) rather than an individual, refusing to hear what she is saying or validate her lived experience. The scope of the care Dove receives also remains firmly grounded in the real world, as “In another age and time, Dove might have stayed in that hospital for years … But this was a day of recession and tight budgets and insurance companies running out of funds. The insurance would not pay for months and months of hospitalization. Dove stayed only one week” (148). Even when Wing has gone, Dove’s life does not go back to how it was before: in the aftermath of her dramatic expulsion of Wing’s soul in the mall fountain, she has to face a crowd of angry and horrified onlookers and when she returns to school, she finds that she has lost almost all of her friends. Dove has to do the hard work of rebuilding relationships, forging new connections, and finding a space for herself in the world following this transformative experience. There are no easy ways out and no shortcuts.

In Twins, Mary Lee and Madrigal are actual identical twins. Most of the people they encounter cannot tell them apart and Mary Lee believes that she and her sister live within a largely self-contained world, as “They never did anything without each other … Girls as beautiful and as incredibly alike as these two were not girls so much as an Event” (6). Mary Lee’s sense of self is inextricably linked with that of her sister and she often thinks of and refers to the two of them collectively rather than as separate individuals. At the beginning of Cooney’s novel, Mary Lee and Madrigal’s parents have decided to separate them, keeping Madrigal at home with them while they send Mary Lee to a boarding school across the country in an attempt to encourage their individual development and disrupt this codependency. Mary Lee is outraged, Madrigal thinks it’s a fine idea, and the girls’ parents send Mary Lee off, ignoring all of her objections.

Once Mary Lee is on her own, she has a hard time figuring out how to function as an individual. She clings to the specialness of her relationship with her twin, though her new classmates refuse to believe that she actually has a twin sister, and while Mary Lee made friends easily when she was a matched set with Madrigal, she struggles to form any connections with her peers at her new school. Mary Lee is miserable and her unhappiness is only compounded when she realizes that Madrigal is thriving without her—including a new boyfriend who adores her—and that she doesn’t seem to miss Mary Lee at all. When Madrigal comes to visit Mary Lee at her school for a long weekend (against their parents’ wishes), it all goes from bad to worse as Mary Lee’s peers love Madrigal and are even more unimpressed with Mary Lee after having this basis for twin-ly comparison … right up until Madrigal suggests they swap clothes and identities to give Mary Lee a chance for a fresh start with the other girls. This isn’t a good plan to begin with—the twins have quite different personalities, which makes this a less-than-straightforward swap, and when they realize they’ve been tricked, isn’t it likely the other girls will be angry rather than impressed?—and it gets even more complicated when a ski lift accident sends Madrigal (who is pretending to be Mary Lee) plummeting to her death. In the aftermath, everyone assumes Mary Lee is Madrigal and Mary Lee decides to let them. After all, everybody likes Madrigal better anyway, Mary Lee reasons, so why not just step into her dead twin’s charmed life?

As with many of Cooney’s other books, she keeps the horror here firmly grounded in reality as Mary Lee (now pretending to be Madrigal) goes back home, where she realizes that Madrigal’s life isn’t exactly what it seemed. Madrigal’s boyfriend Jon Pear is unsettling, with Mary Lee finding herself vacillating between terror and desire, and all of the other kids at her school either hate her or are scared of her, though she can’t figure out why. No one comes to talk to her or offer their condolences at her sister’s funeral service. At school, she tries to reestablish a connection with her old friend Scarlett Maxsom, only to have Scarlett’s brother Van rush up in a fit of rage to protect Scarlett from Mary Lee/Madrigal and demand that she stay away from his sister.

It turns out that their peers have plenty of reasons to be terrified of, and angry at, Jon and Madrigal, because their idea of a good time is terrorizing and endangering their fellow students in a sick game they have contrived. They lure an unsuspecting victim into their car, drive them to a dangerous part of the nearby city, and leave them there. As Mary Lee watches out the window as she rides along with Jon and their latest victim Katy, she “could see into the broken windows and falling metal fire escapes, down the trash-barricaded alleys and past the sagging doors of empty buildings … A gang in leather and chains moved out of the shadows to see what was entering their territory” (132). Jon stops the car and tells Katy that she should move to the front seat with them and when she reluctantly gets out of the car, he locks the doors and begins to drive slowly away as she chases after them, banging on the car windows, panicked and begging to be let back inside. After he has enjoyed Katy’s fear for a while, Jon drives away, abandoning her there, where anything could happen to her. As Mary Lee asks her horrified questions, she discovers that this is a frequent and favorite hobby of Jon and Madrigal’s and that Scarlett had been one of their previous victims, traumatized when she was swarmed by rats.

This is a transformative experience for Mary Lee, fundamentally changing the way she sees her sister and the world around her. This is more unsettling than any supernatural explanation, as Mary Lee reflects that it was “Evil without vampires, evil without rituals, evil without curses or violence … The simple and entertaining evil of just driving away” (134). When Mary Lee asks Jon why they haven’t been caught and stopped, why those they terrorize never tell, he gleefully says that “Victims always think it’s their fault … They blame themselves. They tell half of it, or none of it, or lie about it, or wait months” (137). Mary Lee sees a chilling example of this when she talks Jon into letting Katy back into the car, watching in shocked horror as he soon “had Katy giggling to please him. He had Katy admitting that the night had been a real high … She actually said thank-you after she said good-bye” (148). Whatever their motivation for doing so, the silence of Jon and Madrigal’s victims—presumably now including Katy—has allowed them to continue this game with new and unsuspecting targets.

Jon also unwittingly provides Mary Lee with a new perspective on her connection with Madrigal and reveals a horrifying betrayal. While Mary Lee has cherished the bond she shares with her twin, even while they were separated by thousands of miles, Madrigal despised her. Madrigal was annoyed by Mary Lee’s attempts to connect with her and saw Mary Lee as a useless burden, rather than as the other half of herself. Mary Lee was clearly in some danger, as her parents confess that they sent her away to boarding school in order to keep her safe from her sister. When Jon demands that Mary Lee/Madrigal choose their next victim, he tells her “It’s your turn. I saved your turn when you were offing Mary Lee” (120). There is no clear sense of how Madrigal intended to kill her sister, whether the switching of their clothes was part of her murderous plan, whether Madrigal had second thoughts, or whether what happened with the ski lift was a freak accident or a moment of self-sacrifice. Despite everything she learns when she steps into Madrigal’s life, Mary Lee cannot face a reality in which her own twin would want to kill her, so she shuts the door on that revelation and simply refuses to think about it.

In the end, of course, Mary Lee stands up to Jon and reveals her true identity to her friends and family. It turns out Mary Lee’s parents knew all along that she wasn’t Madrigal and didn’t say anything, adding to the pile of misguided parental decisions that seem to abound in Cooney’s novels. When Mary Lee confronts them and asks them why they didn’t tell her they knew, they confess “We just stood there and let it happen” (172), a damaging instance of passive inaction that links them unsettlingly to Jon Pear, though their intent was very different. This theme of inaction resonates throughout Twins with a wide range of characters: Mary Lee lets the girls at the boarding school assume she’s Madrigal in the immediate aftermath of the accident, her peers do nothing to stop Jon and Madrigal from terrorizing other victims, and Jon and Madrigal stand by and watch a man drown, condemning him to death through their refusal to take action. Mary Lee distinguishes herself and finds courage through her refusal of this passivity, her commitment to not silently go along, and her insistence on taking action.

Things take an unexpected Lord of the Flies-type turn when Mary Lee’s peers have decided that they’ve had enough and that Jon needs to be stopped. They may have been unable or unwilling to challenge both Jon and Madrigal, but now that he’s on his own and Mary Lee is on their side, they are emboldened to take him on, surrounding him at the winter carnival, cornering him near a patch of dangerously thin ice, and gleefully looking forward to watching him drown. Mary Lee attempts to be the voice of reason, objecting to the crowd’s decision with the admonishment that “It isn’t right … We have to be decent, whether Jon Pear is or not” (178). Jon rejects her kindness and a few moments later, also rejects any chance of redemption, when a small boy named Bryan falls through the ice and Mary Lee shouts for Jon to save him. Jon stays focused on his self-preservation, Mary Lee saves the boy who fell through the ice, and when she returns to her peers, Jon is dead. Mary Lee doesn’t know exactly what happened: “This mob. Her new friends. Had they held him under? Had they trampled him when she thought they were rushing to rescue Bryan? Or had Jon Pear slipped of his own accord, and just as he never rescued anybody, nobody rescued him?” (182, emphasis original). After brief consideration, she realizes the only way she’ll ever know for sure will be to ask and she decides she’d really rather not know, remaining silent as her friends close around her and carry her off, as she takes her first steps into her new life.

There is a tidiness in the clear demarcation of identities in Cooney’s The Perfume and Twins: in each of these novels there is a good twin and evil twin (whether physical or incorporeal) that at first glance may appear quite simplistic. After growing awareness and a struggle for agency, the good twin emerges victorious, more aware of the possible evils in the world around her, perhaps a bit more jaded than she was at the start, but still fundamentally virtuous. The evils presented here aren’t all that tempting and there doesn’t seem to be any real threat of seduction, as both Dove and Mary Lee are repelled by the evil they see, feel, and experience, reaffirmed in their goodness at every step of the way. This doesn’t necessarily make it easy to overcome the challenges these evils pose, but it does result in a fairly straightforward conflict.

However, once we turn to the negotiation of good and evil as a process of self-reflection and catalyst for identity formation, it gets a bit more complicated. The Perfume’s Dove does not want to be evil, but there are moments when she wishes she could be different—that people wouldn’t always see her as sweet and innocent, that she could be more outgoing and take more risks, that she could shake up her wardrobe and wear something other than soft, pastel colors. While she rejects Wing’s evil intent and her violence, this persona does give her a chance to try on a different way of being in the world, one where she makes choices and stands up for herself, rather than passively going along with the expectations dictated by her family and friends. In Twins, Mary Lee also must shift the way she sees herself and who she wants to be, needing to define herself as an individual in the wake of the realization that her sense of self as one part of a set was fundamentally flawed. Mary Lee has the extra challenge of having to reframe her understanding of almost every relationship in her life – her sister, her parents, her friends—to find a way to redefine these connections and move forward. For Dove and Mary Lee, good and evil are tangible presences in their worlds as they discover that their own familiar faces hide terrifying secrets, there’s no one they can really turn to or trust without reservation, and in the end, it is up to them to stand alone against the darkness that seeks to destroy them.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.