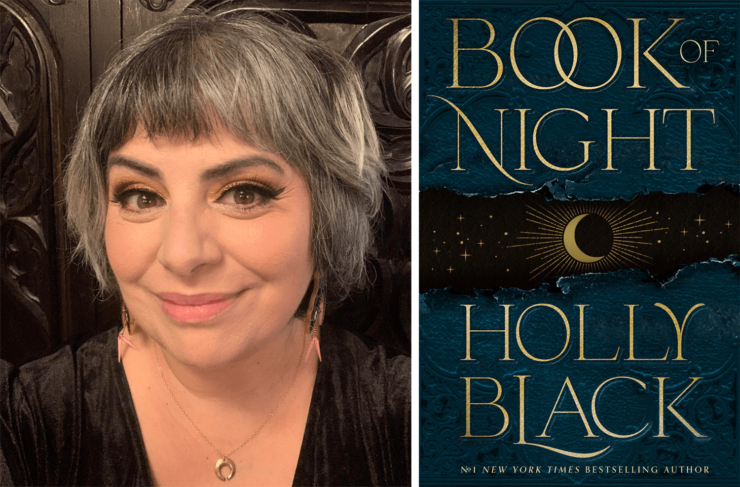

I am, like many readers my age, sentimental about the work of Holly Black. I first encountered her writing as a teen, and her novel The Darkest Part of the Forest helped reignite my love of fantasy after post-college years spent thinking my reading needed to be literary in order to be worthy. But as you and I both know, there is absolutely nothing like stepping into a fictional Faerieland. Holly Black knows this too.

Her decades-long career has seen some of the most iconic fantasy worlds in children’s and young adult literature. Reading her work gives me the same feeling I had when I was little, spending long summers in the woods behind my house, imagining myself lost in an enchanted forest. I was a changeling child then, not unlike many of Black’s protagonists who find themselves crossing between the human world and fae country. So it was a delight to learn that Holly Black grew up about 45 minutes from the town I grew up in in Central New Jersey. It made sense to me, then, why Holly Black’s books connected with me in that way. As my friend Molly Templeton describes, “[T]here’s a specific, netherworldly sense of place: Black’s stories often take place in in-between towns, not the country or the city, boundarylands where things and people cross over.” Black is exploring the space where the mundane backyards transform into fantastical woods, and the adventure to be found in that transformative space. And with beloved works like The Spiderwick Chronicles and the Folk in the Air series, it’s been quite the exploration.

When I spoke to Black ahead of the release of her newest novel, Book of Night, I could not, despite my best efforts, remain cool, and instead started our conversation by gushing about this fairly arbitrary connection I’ve found and my curiosity about how life in New Jersey might have filtered into her writing. “A lot of the spaces where I grew up, particularly the Asbury Park of that time, were not what I think of as the suburbia that we see in movies and TV, which is those cookie cutter houses. And I thought, this does not resemble the suburbia that I know—it is a strange place, it has a lot of liminal spaces, it has a lot of abandoned structures. Yes it has strip malls, but a lot of times they are backed into woods. You have this really interesting environment that I really didn’t feel like stories and films about suburbia usually engaged with,” she explains over Zoom.

Buy the Book

Book of Night

Book of Night is Holly Black’s first book for adults. It follows Charlie, a young woman working as a bartender as she tries to move away from her past as a thief. But she has a talent for finding things other people don’t want found, and people in her town know this. Turns out it’s pretty hard to escape who you once were, and Charlie soon gets pulled back into a world of shadow magic, shady dealings, and power-grabbing magicians. As so many of us have to do as adults, the book sorts through Charlie’s questionable choices alongside the traumas of her past. Her life is marked by neglect, abuse, and con artistry. It’s no wonder she wants nothing more than a normal life with boyfriend Vince, and to see her sister go to college.

Black is the latest of a growing group of authors moving into the adult space after a long career in the young adult sphere, joining the likes of Leigh Bardugo and Veronica Roth. If this is a shift in speculative publishing, it’s not necessarily a genre redefining one—after all, a large amount of older readers enjoy YA, and after an unsuccessful attempt to create a New Adult category to bridge the gap, there are more and more books labeled as having “crossover appeal”. The delineation between adult and YA is a moving target. Depending on who you ask, it’s either about the age of the characters, the age of the intended audience, or whether or not “adult” topics—sex, drugs, and taxes—are present. But for Holly Black, who describes herself as having “washed up on the shores of YA,” it’s a daunting transition into adult fiction: “I’m nervous! I’ve had a career in kids [literature] since 2002. And with my first book, I thought it was an adult book because there were lots of adult books about 16 year olds when I was growing up. There wasn’t such a sharp line, YA wasn’t as big. Tithe is the story of a girl who discovers that she’s a fairy changeling and I thought that if she started that at 30, it wouldn’t seem right. Maybe she should have figured it out by then… but I had always told myself, at some point I’m gonna go back to adult.” Book of Night marks that return, but it feels like a natural progression for Black. Though she mentions that she doesn’t necessarily feel a need to grow alongside her readers, it does seem like a natural move for the author.

Still, Book of Night was a challenge, both during the writing process and the publishing process. She tells me it is nerve-wracking to “feel like a debut again”, and acknowledges that an adult audience is likely to expect different things from a fantasy novel than a teen audience. But she shirks the idea of drafting a book towards a particular audience, instead preferring to write for her reader self, rather than any imaginary readership, because she’s the only reader she can ever truly know. “We like weird stuff, people like weird stuff, so giving ourselves permission to write towards that weird is really useful. Then the horrible truth comes that your book’s coming out and people will see it, and that’s very upsetting news!”

Black describes working through many previous versions of Book of Night, workshopped with writer friends Kelly Link and Cassandra Clare, before discovering the right path through the story she wanted to tell. “I was really interested in the idea of stagnation that comes with adulthood. It becomes harder and harder for us to move out of the spot we’re in. And scarier to move out of the spot we’re in, chaos is no longer our friend. As teens we embrace chaos.” The chaos of our teen years is a subject Black has explored in her work for younger readers, but of course, the ‘young woman steps into her power’ narrative gets complicated when the young woman has to pay bills and take care of her loved ones. Charlie’s sister, Posey, wants nothing more than to be part of the magical world, but is stuck doing tarot readings over the internet. Charlie’s partner, Vince, seems like a safe and reasonable choice for her, despite coming from a more privileged background, but their relationship also gets complicated as the story unfolds. Over the course of the narrative, Charlie juggles emotional stakes alongside magical ones. “I knew what Vince’s story was,” Black explains, “and I think a big problem that I had was that for a long time I thought that he was the protagonist. And it turns out that nobody wants stagnation more than Vince wants stagnation—which is untenable! He did not want the book to happen to a degree that I could not get around. And then as I realized it was Charlie’s story, and as I learned more about who she was, the book came into focus.” Clearly, Black’s hard work paid off, and Charlie’s story has hit home with many adult readers who are coming to terms with similar emotional realities.

Of course, following Charlie’s story means we follow as Charlie’s choices lead into a world of darkness. Part of the firmly adult perspective of this book is that the repercussions of those choices are more severe, and that, as Black shares, instead of Charlie making her first mistakes she might be making her last mistakes. But the mess is part of what makes Charlie so compelling as a protagonist—even if you’re a reader, like me, who gets frustrated when a character decides to do something we ourselves wouldn’t do, we also know that in such situations a good decision is near impossible, and perfection would be narratively unsatisfying. Black understands the need for complicated and messy female characters: “I love characters who make mistakes, and I love women who make mistakes and make bad choices, and screw up. To me that is the area that I am most interested in writing about. Because I don’t think it’s something we allow female characters to do. We often hold them to a much higher standard. And I am interested in lowering that standard,” she says, with a wide grin and a mischievous laugh.

Morally grey and complex characters are Black’s specialty—there is a balance of strong heroes (and in particular, young girls who kick ass) and darker characters we love to hate. Fantasy readers, of course, love a good villain, and in particular, a hot villain, which is an area Holly Black excels in. This is one of the joys of fantasy writing: terrible human traits can be exaggerated and turned into something compelling and vital. Black shares the story of a class she taught with Cassandra Clare on this very subject, during which they discussed the scale of forgivable to unforgivable crimes in fiction. “We made a chart — we talked about how in real life, you would be friends with someone potentially who was a bad tipper, or who even would skip out on tipping. But probably you would not be friends with a murderer. But in a book, that is reversed. If your friend’s a thief in real life…but in a book they’re the hero. They’re automatically the hero, there’s no way around that. A bad tipper? You will never forgive that person. There’s no way a bad tipper can be redeemed in a book. We do not forgive characters’ petty crimes. You’re aiming for the epic. Murder is often metaphorical — bad tipping is real. We do not interpret characters through the same lens that we interpret friends.” Of course, she goes on to acknowledge that fan-favorite bad boy faerie Prince Cardan (of the Folk in the Air series) is that bad tipper–but that he is also the product of a terrible world, where the morality scales are tipped even further.

One of my favorite things about talking to writers, and fantasy writers in particular, is the glee they project when talking about torturing their characters. When I ask about her writing process, she happily tells me about her approach to worldbuilding, and the work of weaving together the plot and the magic system to create the “perfect torture device for the main character.” In Book of Night, the torture for Charlie is based around Black’s idea of the shadow self, or “parts of us we don’t acknowledge—our shame and our fear and our desire, that’s Charlie’s story. It has to be Charlie’s story for it to be Charlie’s book.”

Black makes no effort to disguise the work that goes into her stories. With a career like the one she’s had, she’s bound to have some perspective on writing, both as an art and as a career. “When I began writing I really had trouble seeing structure, and I have gotten better at understanding the larger picture and understanding more about the individual parts. Like, what is the relationship of pacing to specific scenes, and how you get the characters who want things to want them in a way that is narratively interesting. For instance, how do you make a magic system that is story generative, rather than something that seems cool? I learned how to think about the way that textural stuff, in terms of the prose, is related to metaphorical stuff.” In an interview with fellow author V.E. Schwab, Black said that her philosophy of writing is to “make broken stuff and then fix it”, and she affirms that re-writing is an essential part of her process. “I have some idea of magic and texture, then I start writing the character, then I need to reevaluate the magic.”

It is this process that has made Holly Black a massive success in the fantasy genre. Readers continue to come back to her worlds for this very reason—everything feels synchronized, the magic and the plot go hand-in-hand. But Holly Black affirms that whether she is writing Young Adult or Adult, her love for the weird remains strong. And where there is weird, there is a loyal and engaged audience.

“As a kid I thought, I’m a weird kid, people don’t like the stuff I like. And one of the greatest and most interesting things is learning that people do like the stuff I like. People do like weird stuff! Being able to talk about stories and characters and all that has been about allowing myself to realize that we are all in this together, and that our flaws are part of what make us interesting, in the same way that flaws are what make characters interesting.”

[Quotes have been gently edited for clarity]