All most people know of Mac and Me is a 15-second clip.

Viewed in full, this 1988 E.T. knockoff is justifiably considered one of most abysmal cinematic travesties ever made. The following is not a critical re-appraisal. At least I hope not. But it was once an important film for me, very dear to my heart. Why?

E.T.: the Extra Terrestrial came out before my friends and I were born, but our parents excitedly counted the years until we were old enough to watch it on home video. They hyped this legendary family film non-stop, and arranged a sleepover centered on the viewing, in the private carriage house of our biggest-housed friend’s big home. In front of the TV and VHS was a popcorn bowl filled with Reese’s pieces, E.T.’s Hershey-funded fave. We were all but obligated to worship the little alien.

Spielberg’s blockbuster was fine. But it was the 90s. I’d already seen Mac and Me. Multiple times. So, this terrestrial was extra.

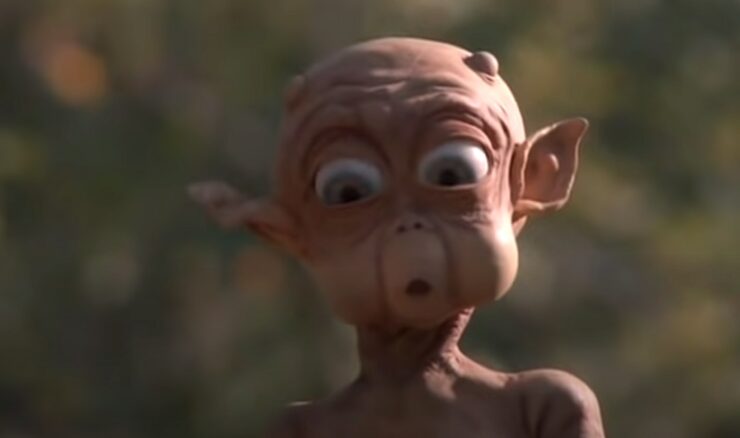

E.T. is a weird dude, but Mac and Me took the repulsive-but-cute thing way past the point of reason. M.A.C. (“Mysterious Alien Creature”) and the rest of his human-sized family are wrinkly elf-eared naked liver-spotted testicle-headed fuckers who toss up the Wu-Tang symbol instead of the glow finger, and communicate with a whistle they can hear across miles of California desert. They also love pounding Coca-Cola, which resembles the fluid they suck out of the ground on their galactic homeworld, a moon of Saturn. “This must be like what they drink on their own planet,” says Eric (this movie’s Elliott), like a good little shill. Coke saves lives.

Elevating product-placement to its inevitable orgiastic conclusion seemed to be the goal of R. J. Louis, who produced Mac, his E.T. for an even more cynical generation. Although many viewers understandably assume that McDonald’s financed the whole film as a cash-grab, it seems R. J. hustled tooth-and-nail to get their involvement. An ahead-of-his-time visionary for shameless corporate tie-ins, he had worked for McDonald’s, and clearly wanted to make it look like the most lit place on earth. An extended “dance contest” in the middle of the film sees the restaurant break into full choreography, complete with football players, ballerinas, young Jennifer Aniston, and Mac in a teddy bear suit. Mission accomplished, RJ.

Somehow the dogshit Mac and the Best Picture-nominated E.T. were on the exact same plane for me as a kid, with no noticeable difference in quality.

“Approval/disapproval is keeping you from a direct experience.” -Viola Spolin

For our kid minds, quality was a myth, and each entertainment was exactly the same thing. The cheap imitation—which inspired a Washington Post critic to write: “E.T., call lawyer”—was a welcome leveling up. John Williams scored Spielberg’s film, but Alan Sylvestri brought even more of that post-Back to the Future heat. E.T. had Reese’s pieces, but Mac had the entire McDonalds menu. Sure, the bike chase was thrilling, but did it compare to a runaway wheelchair on a Los Angeles freeway? Hell no.

Mac and Me, for me, was also about representation. It featured a disabled protagonist. Eric, a wheelchair-user like my mom, was portrayed by an actual wheelchair-user. To this day, a rarity in Hollywood.

In 2004, the actor Paul Rudd began a long-running bit on Late Night with Conan O’Brien that brought Mac back with an ironic vengeance. He’d intro a clip from some project he was there to promote (everything from a sneak peek at the Friends finale to an exclusive look at Marvel’s Ant-Man) and then, without fail, the audience and host would be smacked with 15 hot seconds of Mac:

Eric loses control of his wheelchair and rolls down a hill. A little girl calls out his name and scampers after him. In close-up, his wheelchair brake snaps off. Boy and wheelchair plummet off a cliff and into a lake. A hideous alien puppet head pops up from somewhere nearby, filling the frame.

For most viewers, this was a hilarious, bizarre non-sequitur. I was not most viewers. I had the joyous reaction of the familiar, “that’s Mac & Me!” followed by an immense wave of shame. I remember being genuinely frightened by that scene as a kid. When I watched Eric roll down the hill in the viral clip, I saw my own very real fears. I remember the first time I watched the movie, experiencing the terror of this loss of control. I recalled learning the importance of mom’s brakes, recalled the tense experience of holding the wheelchair’s handles and slowly easing down a steep hill in the neighborhood or down a slanted sidewalk. The clip made cinematic reality of my nightmare: what could happen to her if I let go.

In an earlier moment, Christine Ebersole, playing Eric’s mom, wheels him through their new house on an excited tour: “Did you notice my dear that there is not one step in the entire place?” she beams, “Low counters, wide hallways, and you can see out of every window!” This was true of my house. Eric was like my mom, and Jade Calegory, the actor with spina bifida who portrays him, navigates space with the naturalism I knew from my home life. As he transfers from bed to wheelchair, and rolls through public places, the film normalizes his experiences with limited mobility. It isn’t a big deal. Eric is just the kid who meets the alien, who happens to use a wheelchair. He’s never portrayed as pitiful or tragic, nor does the supernatural Mac “heal” him. The alien fam rallies to resurrect him from the dead, sure, but a lesser film—if it’s possible to imagine a lesser film—would have them vanish his spina bifida and restore him to some ableist concept of “normalcy.” Instead, the final scenes find Eric still a wheelchair-user; a happy, coping kid with testicle monsters for friends.

This movie came out before the Americans with Disabilities Act passed.

I promise I’m not trying to cancel Paul Rudd. The scene he can’t stop screening is undeniably filmed and edited in a laughable way. But the snapping brake continues to haunt me.

Over the next fifteen years, as Rudd’s cursed attic painting aged in his stead, he pranked Conan again and again with the clip, and every instance would greet me the next morning on YouTube. In 2021, Rudd trotted the clip out at Conan’s farewell show. Finally, I thought, it’s over. But then, just weeks ago, Rudd appeared on Conan’s podcast, and we all knew what was coming. The clip was only audio—even worse, because we listeners had to conjure up the visual joke ourselves, replay it in our minds. He knew we would. We’d see the little girl scramble through the grass, the wheelchair’s brake break off, the fall, the splash, the bug-eyed Mac react.

I was inspired to re-watch the whole movie. It is, of course, worse than I remember. What stood out this time is that Eric is shot and killed by cops in the film’s climax, after a half-baked allegory for racist state violence, and before a naturalization ceremony in which the aliens become American citizens. Mac and Me really does do it all. Nearly all of it badly.

It’s still one of the only major motion pictures starring an IRL wheelchair user. It had to be Mac and Me. A movie with no value to anybody, except maybe the parasitic nostalgia that lives inside me and demands to be fed. I either have to go suck Coke out of the ground, or call my mom.

Buy the Book

Sticker

Henry Hoke is the author of five books, most recently the memoir Sticker from Bloomsbury. Open Throat, a novel, is forthcoming in 2023 from MCD/FSG and Picador. He edits humor at The Offing, and lives in New York City.