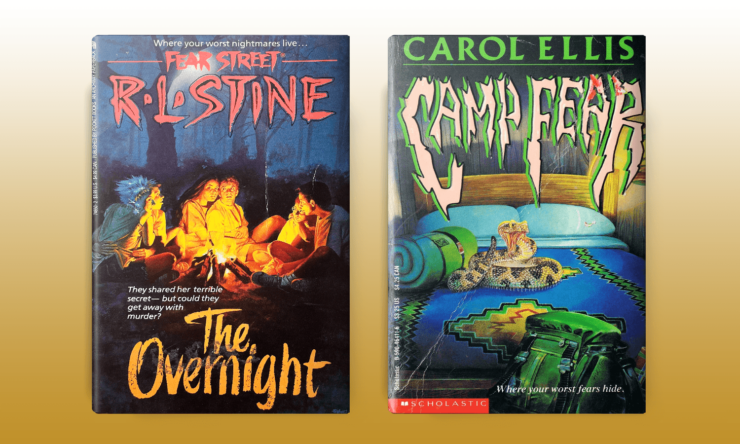

Sometimes getting back to nature can be a perfect break from the day-to-day demands and stressors of modern life: the wind in the trees, stars overhead, fresh air, maybe an invigorating hike or a cozy night spent around a campfire. For the protagonists of ‘90s teen horror novels, the wilderness offers this escape, as well as a chance to get out from under the constant surveillance of their parents and (to a lesser extent) away from the social stratification of their communal peer group. However, while the high school hallways of teen horror are wild enough, the great outdoors holds its own set of challenges and dangers. The teens in R.L. Stine’s The Overnight (1989) and Carol Ellis’s Camp Fear (1993) venture into the woods and find a whole new set of horrors.

These two novels share several characteristics that align them with the larger subgenre of wilderness horror, including separation from “civilization” and its modern conveniences, isolation and the resultant demand for self-sufficiency, and omnipresent dangers that include the potential for drowning, falling off a cliff, or encountering predatory or poisonous wildlife. In addition to telling their own stories within the unique ‘90s teen horror context, both of these novels also evoke horrors that have come before, with Stine’s The Overnight reminiscent of Lois Duncan’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (1973) and Ellis’s Camp Fear having some good Friday the 13th (1980) vibes, which makes for an interesting contextualization of these novels with the genres and texts upon which they draw, from young adult suspense to the slasher film.

In The Overnight, a group of six students from Shadyside High School are set to go on a camping trip with the Wilderness Club when their advisor is suddenly unavailable and the trip is postponed. But their parents have already given permission, so they go anyway, expecting an even more fun-filled trip now that there will be no adult supervision. The six are a mixed bag of different personalities, already laying the foundation for conflict: Della O’Conner’s a girl who is used to getting everything she wants, including her ex-boyfriend Gary Brandt, who is also going along on the trip. Suki Thomas is a “bad girl” and Della’s best friend Maia Franklin is a rule-following worrier. Pete Goodwin is a preppy straight arrow guy, while Ricky Schorr is a joker. They canoe across to the island and hike through the woods to find a campsite, enjoying the freedom and isolation … right up until Della nearly gets murdered in the woods by a random stranger who also just happens to be on the island too. As she fights to get away from this man, she shoves him away from her, he topples down a nearby ravine, and seems to break his neck. When the other members of the Wilderness Club find Della standing over a dead body, they check him for a pulse…and find nothing.They decide the best course of action is to cover his dead body with leaves and tell no one. They make a collective pact to keep this secret, but it definitely puts a damper on the rest of the camping trip.

Once back in Shadyside, they struggle with keeping this secret, especially Della and Maia, and the stakes climb higher when they begin to get notes letting them know their secret is not so safe. The first note Della receives reads “I SAW WHAT YOU DID” (68), with the taunting and threats escalating from there. This pattern draws on Lois Duncan’s I Know What You Did Last Summer, a 1973 young adult suspense novel about a group of teens who hit-and-run a boy on a bike and then swear one another to secrecy, a narrative pattern that has been adapted and remade now in countless novels, television episodes, and movies, most notably the all-star 1997 film of the same name. In both I Know What You Did Last Summer and The Overnight, the teens weigh the right thing to do against what they stand to lose and they choose to stay quiet, though they remain haunted by that fateful night and the guilt they can’t shake. This is amplified in both cases by a mysterious someone harassing them and threatening to reveal their dark secret.

There are some notable differences between the two narratives: in I Know What You Did Last Summer, the little boy is dead and the grief destroys many of those who loved him. The person who threatens the four teens is serious about getting vengeance and there’s real violence as he shoots one of the boys, assaults one girl in her apartment, and attempts to strangle another girl. They agree to stay silent in part because they were drinking and smoking marijuana before the accident and the friend who was driving is eighteen, meaning he’ll be tried as a legal adult if the truth comes out. Even once the teens confess (which they inevitably do), nothing is going back to “normal.” In contrast, at the conclusion of The Overnight, Stine drops readers off pretty much right where they began, with very little in the teens’ lives fundamentally changed. They wrestle with their guilt and the moral quandary of whether they should report the man’s death, but they find out that he’s a bad guy who robbed and shot someone, then fled to hide out on the island (which seems more Hardy Boys than Fear Street). Also, he’s not actually dead. When he attacks Della for the second time, he tells her that he has a “very faint pulse point” (136), so it’s reasonable that they thought he was dead, but he’s not. They come clean, the bad guy is captured, and the teens get in trouble for lying to their parents and going on an unsupervised overnight trip, but that’s about it. They return to their everyday lives and fall back into their established routines and roles, aside from the fact that Della’s no longer trying to win Gary back and is dating Pete instead. They don’t seem to have learned any important life lessons about honesty or taking responsibility for their actions, and Della’s big takeaway is that camping sucks. The no-impact conclusion is a bit of a let down, honestly.

We also need to talk about Suki Thomas. Suki Thomas appears in several of Stine’s Fear Street books, but almost always at the periphery and usually making out with someone else’s boyfriend. But in The Overnight, Suki is right in the heart of the action, one of the six Shadyside students who take their unsupervised and ill-fated trip to Fear Island, and she is brought into camaraderie with several of her peers as they conspire to keep their dark secret. Suki is, quite frankly, a badass and deserves better than she got in Stine’s Fear Street novels. As Stine describes her in The Overnight’s opening chapter, “She was very punky looking, with spiky platinum hair and four earrings in each ear. She was wearing a tight black sweater with a long, deliberate tear in one sleeve, and a very short black leather skirt over dark purple tights. The purple of the tights matched her lipstick perfectly” (3-4). Suki Thomas is too fabulous for Shadyside and really doesn’t care what anyone else thinks or says about her. She’s independent, confident, and self-possessed … which of course means all of the other girls hate her. She gets on fine with the guys, but that’s probably because she has “quite a reputation” (4), which Stine haphazardly builds over the course of the series, where nearly every time Suki is mentioned, the other characters overtly note that she’s with a different guy or with someone else’s boyfriend. In The Overnight, she’s spending time with Gary, who is Della’s ex-boyfriend, and while Della’s the one who broke up with him, she didn’t really mean it, she just wanted him to grovel and beg her to come back to him, but he didn’t. Instead, he started seeing Suki. But Della has decided she wants Gary after all and when she gets him back “Suki could just find someone else. That wouldn’t be a problem for her” (16). What Suki wants never comes into the equation for Della, because as a girl with “a reputation,” Suki doesn’t really matter. There’s no need to consider her feelings or who she is as a person. Suki is overtly slut-shamed throughout The Overnight (and the larger Fear Street series), but even more than that, in this particular moment, she is completely dismissed, erased from Della’s narrative as not worth a moment’s consideration and completely inconsequential to Della’s desires or planned course of action. Suki is amazing, but unfortunately, to the best of my recollection, The Overnight is the closest we get to a Suki-centric Fear Street story and it’s not good enough.

Camp Fear begins with a premise quite similar to that of Friday the 13th, with a group of teens arriving at a camp in the woods to get it cleaned up and ready for the campers who will soon be arriving. There are a couple of marginally older supervisors who keep heading into town for supplies, leaving the teens largely unsupervised as they clean the cabins, clear the trails, and otherwise get things set for the camp’s opening, though adolescent high-jinks are, of course, inevitable. When they take a break from working on the camp, the teens swim, canoe, go exploring on a nearby island, and tell stories around the campfire. They also play pranks that get increasingly ugly as the teens begin to capitalize on one another’s greatest fears, which makes it challenging to distinguish everyday bullying from real danger when someone begins targeting them. For example, when Steve throws Stacey into the lake even though he knows she’s scared of the water, he’s being a real jerk, but when a rattlesnake mysteriously shows up in the boys’ cabin, is it one of their friends playing a cruel and dangerous trick on Steve (who is terrified of snakes) or is it something more sinister, with an attacker who’s hoping someone gets seriously hurt or maybe even winds up dead? It’s impossible to discern the mean pranks from the actual threats, which puts all of the camp counselors in serious danger. The only way they’re ultimately able to tell who their mysterious attacker has their sights set on is the appearance of targets drawn on their faces in the pictures that hang in the lodge after each attack, which obviously isn’t at all helpful in preventing violence or protecting themselves.

Buy the Book

Seasonal Fears

Like Camp Crystal Lake, Camp Silverlake has some tragedy in its past, in this case, the death of a young boy named Johnny during an overnight wilderness hike. These ‘90s teen horror novels skate around any direct representations of sex or desire, so in Camp Fear, Johnny dies not because his camp counselors were distracted and having sex, but as a result of bullying from his peers. This situates the novel’s narrative of death and revenge firmly within the context of adolescent conflict, which is more likely to resonate with its intended audience and avoid the ire of their parents, whose approval and buying power were often a necessary part of the equation.

Several of the teens who are preparing to be counselors at Camp Silverlake were also at the camp the summer Johnny died and were some of his greatest tormenters, making the connection between the camp’s past and present even more pronounced in Camp Fear than in Friday the 13th, where the camp counselors just had the bad luck of getting the wrong summer job and stepping into the horror in media res, largely unaware of Camp Crystal Lake’s past. In Camp Fear, Steve, Mark, Jordan, and Stacey all teased Johnny when they were at camp together seven years ago. While Camp Crystal Lake is definitely a “bad place,” marked by Michael’s death and shunned by local residents, Camp Silverlake doesn’t have the same reputation and seems to have been in continuous operation since Johnny’s death, which was presumably ruled an accident, with the camp not at fault (but also, where were the counselors? Why was this boy running around by himself in the woods in the middle of the night and no one noticed? The tunnel-vision of childhood and adolescence keeps the narrative focused on the kids’ own experiences and perceptions, with the adults in the story marginalized and largely inconsequential).

Camp Silverlake’s caretaker, Mr. Drummond, also serves as a gatekeeper of the camp’s history, having worked there for years, including the summer Johnny died. While Friday the 13th has Crazy Ralph’s memorable pronouncements of doom, Mr. Drummond is more of the strong, silent type, watching from the sidelines and occasionally stepping in to check on the campers or ensure their safety, such as when he kills the rattlesnake in the boys’ cabin. Mr. Drummond remembers what happened to Johnny and while he doesn’t say much, he seems to want the truth to come to light. When one of the new counselors, Rachel, is putting up photos from the camp’s previous seasons on the lodge bulletin board, she puts a picture of Johnny right in the center, not knowing who he is or what happened to him; after a tense moment of contemplation, Mr. Drummond tells her that “It’s good … You couldn’t have picked a better one” (38). While Johnny was the main target of the others’ bullying, they also harassed Mr. Drummond, treating him as a kind of bogeyman, a pattern they immediately fall back into when they return to Camp Silverlake as teens, despite the older, head counselors’ reassurances that he’s a perfectly nice, normal guy. As Stacey recalls on their first night back at the camp, “I remember we used to scare ourselves to death at night. Every time there’d be a sound outside our cabin, one of us would decide it was Mr. Drummond and we’d all dive into our sleeping bags and hide” (12). Their cruelty toward Mr. Drummond becomes aligned with that toward Johnny, since the tradition in the boys’ cabin was not to hide, but to send some unlucky camper out into the darkness to check, which is what Johnny was doing on the night he fell to his death.

While Camp Silverlake doesn’t have the legendary reputation of Camp Crystal Lake, the returning campers-turned-counselors bring their own baggage with them, reawakening the past and suggesting that adolescent social dynamics are a greater danger than any one specific place could ever be. One of the new counselors named Linda turns out to be the one who is attacking her fellow counselors and also, not coincidentally, Johnny’s sister. While Linda herself never attended Camp Silverlake, she carries letters with her that her brother wrote to her seven years ago, where he told her about how he was being treated by the other children and begged to come home. It’s unclear whether Linda wanted to come to Camp Silverlake as a counselor as an act of personal catharsis or whether she knew the others would be returning as counselors as well and came specifically to seek revenge. As Johnny’s sister Linda recounts the others’ bullying of her brother, Ellis makes it clear that this tragedy could have happened just about anywhere: the others didn’t cause Johnny’s death because of where they were, but rather because of who they were (and to some extent, still are). There was definitely some bad luck involved and none of them intended for Johnny to get hurt, let alone wind up dead. But whether they intended it or not, their actions contributed to his death and it seems unlikely that their behavior would be all that different in other places or parts of their lives. If they’re ostracizing and harassing an outsider kid at camp, it stands to reason that they treat their less popular peers the same way in their own respective hometowns and schools.

While their bullying of Johnny (and its tragic consequences) could have happened anywhere, the setting of Camp Fear is nonetheless important, and the elements of wilderness horror that Ellis draws upon help build the suspense. These teens are isolated in the woods, living in small cabins spread out from the main lodge. To go to the lodge, the shower cabins, or their friends’ cabins, they must pass through the woods, often at night, with only a flashlight to light their way. There are a lot of shifting shadows and creepy noises, which may be just the wind in the trees or an attempted murderer stalking them through the wilderness. There are poisonous snakes and rumors of bears (though no one has ever actually seen a bear). They could drown in a lake or fall off a cliff, and no one would be there to hear them call for help or get there in time to save them. When they begin being targeted—complete with targets drawn around their faces in the posted photographs—there’s not much they can do about it other than hope they won’t be next and try to survive. Seven years before, Johnny died, in part, because isolated in the woods at night, there was no one to turn to for help and no way out of the situation: his choice was being tormented in the tent with his fellow campers or venturing out into the terrifying darkness of the forest. He chose the forest, hoping to end the others’ constant teasing, and died there.

In both The Overnight and Camp Fear, the horrors are a combination of the environmental and the human. The setting contributes to the terrible things that happen: the characters are isolated from the larger world and can’t easily call for help or fall back on adult supervision, they’re unsure of the specific dangers that might lurk in the shadows beneath the trees, and there are plenty of natural threats, from wild animals to the land itself. But the environment is not the whole of the horror, because most of the terrible things that happen come about as a result of the choices these teens make, their refusal to take responsibility for their actions, the lengths to which they go to cover up what they have done, and the guilt and blackmail that follow them.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.