In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Science fiction author Spider Robinson and dancer Jeanne Robinson were both quite well established in their respective artistic fields, and in their marriage, when they decided to collaborate to produce a unique work: Stardance, a tale of bringing the art of dance into zero gravity, and also a story of first contact with alien beings. The story is a delight, full of passion and energy, while at the same time a thoughtful speculation on the impact the absence of gravity would have on the art form of dance.

The 1970s were a rather dispiriting time in American history. The disastrous Vietnam War ended in an embarrassing defeat, while the Cold War, with the threat of a world-ending nuclear exchange, was at its peak. The space program, instead of building on the successes of the Apollo Program, was winding down. Air and water pollution was impossible to ignore, the human population was exploding while populations of wildlife were collapsing, and there were those who argued that civilization itself could soon begin to collapse. The excitement that accompanied the spiritual awakening of the 1960s was fading into cynicism. Some felt that if humanity were going to avoid destruction, outside intervention would be required. All this was in the background when Spider and Jeanne Robinson decided to collaborate on Stardance, a story whose optimism stood in stark contrast to the prevailing pessimism of the era.

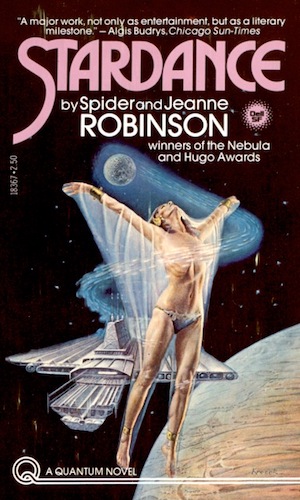

The copy I reviewed was a hardback from Dial Press’ Quantum Science Fiction imprint, published for the Science Fiction Book Club, which was a major source of books for me in the late 1970s and into the 1980s. And while I don’t recall the specific encounter, it was signed and personalized for me by Jeanne and Spider, probably at a science fiction convention during the 1980s.

About the Authors

Spider Robinson (born 1948) is a noted American-born Canadian science fiction writer and columnist. I have reviewed Spider’s work before in this column, including the collection Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, and the novel Mindkiller. You can find his biographical information in those reviews. Following the deaths of both his wife and daughter, and after suffering a heart attack himself, he has not published in recent years, although he did appear as Guest of Honor at the 76th World Science Fiction Convention (WorldCon) in 2018.

Jeanne Robinson (1948-2010) is the late wife of Spider Robinson, with whom she wrote the Stardance trilogy [Stardance (1979), Starseed (1991), and Starmind (1995)]. She was a professional dancer and dance teacher, and served as artistic director for Halifax, Nova Scotia’s Nova Dance Theater, where she choreographed a number of original works. The initial part of Stardance first appeared as a novella in Analog in 1977, and went on to win both the Hugo and Nebula awards in the novella category. The remainder of the book appeared in Analog as Stardance II in 1978. A movie version of Stardance was once in the works, and apparently had even been scripted, but that seems to be as far as the project ever progressed. Jeanne had been considered for NASA’s civilians-in-space program before the Challenger explosion ended that endeavor.

More Than Human

Humans have always been fascinated by the possibility of mental and physical powers far beyond the scope of normal abilities. Stories of beings with such powers are entwined in ancient legends and mythologies; stories of pantheons of gods, and heroes like Gilgamesh and Hercules. And such beings have long inhabited science fiction stories as well, including the Slan of A.E. vanVogt, and the Lensmen of “Doc” Smith. My own youthful imagination was sparked by comic books, filled with characters who were born on other planets, bitten by radioactive spiders, injected with serum by military scientists, bombarded with gamma rays, or whose mutations were triggered in puberty.

In science fiction, as time went by, and authors grew more creative and speculative, the transformations led to characters who were less recognizably human. While his reputation was founded on hard scientific speculation, Arthur C. Clarke proved to have a mystical streak, as shown by his books Childhood’s End and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The ever-useful online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has a short article on the theme of Transcendence that offers a few examples of works that feature this theme, although searching its database for the word “transcendence” provides even more examples.

Though I didn’t specifically seek these tales out, I can remember reading many science fiction stories that contained elements of transcendence. There was a section in Clifford D. Simak’s City where humanity leaves the planet for a simpler life as beings on Jupiter. I remember a number of Keith Laumer books with heroes, often unstoppable warriors, who become something more than human in their endeavors. James H. Schmitz’s tales of telepath Telzey Amberdon followed a young woman who increasingly thought of herself as more than human. Greg Bear’s “Blood Music,” which I read in Analog in 1985, was an absolutely horrifying tale of nanotechnology run amok. In Steven Banks’ Xeelee Sequence, there were many characters who were altered versions of human beings, appearing in all sorts of exotic environments. And the humans in Gregory Benford’s Galactic Center books, locked in combat with mechanical opponents, are themselves as much machine as man.

The concept of transcendence, depending on the author, can be seen as hopeful, inspiring, chilling, and often more than a bit baffling. Spider Robinson’s work is no stranger to the theme, as his tales of Callahan’s Bar, and many of his other stories, often featured humans making connections, whether through empathy or telepathy, which go beyond the ordinary.

Stardance

The book opens with a rather old-fashioned framing device, with first-person narrator Charlie Armstead promising to tell us the true story of Shara Drummond and the Stardance. He begins on the day he was introduced to Shara by her sister (and his old friend), Norrey Drummond. Norrey wants Charlie to record Shara dancing, although he immediately sees Shara doesn’t have a future in the field, being a tall and statuesque woman, not the body type dance most companies were looking for. But Charlie sees her talent, and agrees to help Shara with a solo career. We also find out that videographer Charlie was a dancer himself, his career cut short after a home invasion in which his dancer girlfriend was killed, and which left him with a damaged leg.

Shara’s career as a solo dancer lasts only a few years, and she disappears from Charlie’s life. He begins drinking heavily until eventually, just as he is pulling himself back together, she calls and offers him a job, recording her dancing in zero-G. She has gained the patronage of arrogant space industrialist Bruce Carrington, and use of his orbiting Skyfac industrial facility (Carrington also expects sexual favors from Shara as part of the deal). Much is made of the danger of staying in orbit too long, and becoming irreversibly adapted to zero-G (a concept that has become dated as humanity has gained more experience in space).

At the same time Charlie and Shara are preparing for her dance routines, there are sightings of mysterious unidentified objects moving inward through the solar system…and when the enigmatic creatures, who resemble large red fireflies made of energy, arrive at Skyfac, it is only Shara who understands that they communicate through dance. A United Nations Space Force ship, led by Major Cox, is willing to hold its fire and let Shara attempt to communicate with the aliens. She leaves the facility, establishes a rapport with the creatures, and responds to their dancing motions with a dance of her own, which Charlie is able to record. She reports that the creatures want the Earth for some sort of spawning process, but when she replies with the dance she had been working on, the dance is so powerful and evocative, it convinces the aliens to leave us alone. Shara sacrifices herself to complete the dance, but the Earth is saved.

That bare summary of the first third of the book is just a shadow of the story, which packs a tremendous emotional punch, simultaneously filled with pain and suffused with hope. It is no wonder the novella form of the story won both the Hugo and Nebula that year. After this point, the tale undergoes a significant tonal shift, with the middle section of the book focusing on how Charlie and Shara’s sister Norrey use the money earned from recordings of Shara’s dance with the aliens to form a zero-gravity dance troupe. Charlie, to his delight, has discovered that in zero-gravity, his leg injury is no longer an impediment, and he can dance again. They have a whole host of hurdles to overcome—not the least of which is the inability of most people to cope with the lack of a local vertical, or some sort of visual cue that can help them pretend they are in an environment with an up and a down. The authors clearly did a lot of homework, and it shows, as the setting feels utterly real and convincing (and formulae and orbital diagrams even appear in a few places).

There are the usual brushes with death that space-based novels contain, and at one point Major Cox shows up to save the day. The group finally coalesces into a tightly-knit troupe of three couples. Charlie and Norrey have married. Their manager, Tom Carrington, turns out to be one of those rare people who can adapt to zero-gravity, and it proves easier to take an adaptable person and train them to dance rather than the reverse. He is paired with Linda Parsons, a young girl raised on a commune and one of the rare dancers who could adapt to zero-gravity, and their relationship is one of those rare ones where opposites attract. The last couple is two men, Harry and Raoul (notable because in those days it was still rare to see a book where a gay couple was portrayed as happy and stable). Harry Stein is the engineer who supports the troupe’s efforts with construction and equipment, (his name an apparent nod to space advocate G. Harry Stine, who provided advice to the authors), and Raoul Brindle is a musician and composer, who also works as their stage manager. And their company comes together just in time for the aliens to reappear, this time in the vicinity of Saturn’s moon Titan.

The final third of the story takes the dance troupe, pressed into service along with a military crew and a fractious group of diplomats, to meet with the aliens. Again, a lot of research and care on the part of the authors is evident in the narrative. The mission is staged by the United Nations Space Force, and is led by the competent and incorruptible Major Cox (now referred to as Commander because of his position). The diplomats, who are supposed to represent all humanity, come from the United States, Russia, China, Brazil, and Vietnam. Some are unfortunately more concerned with their own agendas, and willing to go to extreme lengths in pursuit of their selfish aims. But those machinations are defeated by their more ethical counterparts, the ethics of the military crew, and the dance troupe. The dancers, in the end, become something more than dancers, and something more than human. Stardance is a unique approach to the typical alien encounter story, both in its inclusion of dance as a means of communication, and in its general sense of hopefulness which stood in stark contrast to the pessimism of the era in which the book was written.

Final Thoughts

For a book written 45 years ago, but set in the near future, Stardance has stood up remarkably well. Progress in space is moving more slowly than the authors expected, but other than some anachronisms like recording visual media on tapes, a few outdated cultural references, and ideas about the danger of irreversible adaptation to zero or low gravity, the story could easily be set within the next few decades. And, like all of Spider Robinson’s work, the tale is well crafted and emotionally satisfying. I would recommend it to anyone looking for a good read.

I’m now looking forward to hearing from you, especially if you’ve read Stardance. And I’d also like to hear how you think it stacks up against other portrayals of alien encounters.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.