When I started this column a few months ago, there were several Christopher Pike books that I remembered particularly fondly and was looking forward to revisiting, including Slumber Party, Master of Murder, Die Softly, Last Act, the Final Friends trilogy, and the Chain Letter duology. (The Midnight Club is my absolute favorite, but I’ll not-very-patiently wait for Mike Flanagan’s Netflix adaptation to come out before we go there). The brightly colored spines, the flashy fluorescent titles, Christopher Pike’s name in that big script-y font at the top of each cover. Just the sight of a Christopher Pike cover—really ANY Christopher Pike cover—takes me back to those feelings of excitement and anticipation, standing in the library or the mall bookstore, book in hand, thrilled to see what he had in store for us this time.

When I returned to The Last Vampire in my most recent column, I was thrilled to find queer representation and diverse perspectives. There wasn’t much—a couple of sentences about how Sita had had female lovers as well as male ones over the last 5,000 years, some flashback scenes set in India, and Krishna as a character—but it’s more than the heteronormative, white-washed world that ‘90s teen horror usually has to offer. While I remembered the Krishna narrative, I had no recollection of the fleeting queer representation from my previous teenage reading of the novel (though growing up in the rural Midwest in the early 1990s, I would have had very few people I could talk to about this recognition anyway, so I may well have noted and then forgotten it). Rereading The Last Vampire now, I was simultaneously excited and frustrated, thinking of the spark of recognition many young readers surely felt, only to have that story remain undeveloped and untold, seen but then silenced. But it seemed a promising start, so I decided to tackle Pike’s Last Vampire series in its entirety to see where it would go and how it would develop, hoping for more queer representation and a satisfying story for Seymour, a nerdy side-character who becomes Sita’s biographer (more on him later). After The Last Vampire, Pike wrote five more books in the series in the 1990s and then returned to it again in the 2010s, so I was also particularly interested in seeing the expanded possibilities for telling Sita’s story in a new millennium. 2,339 pages later, what have I found?

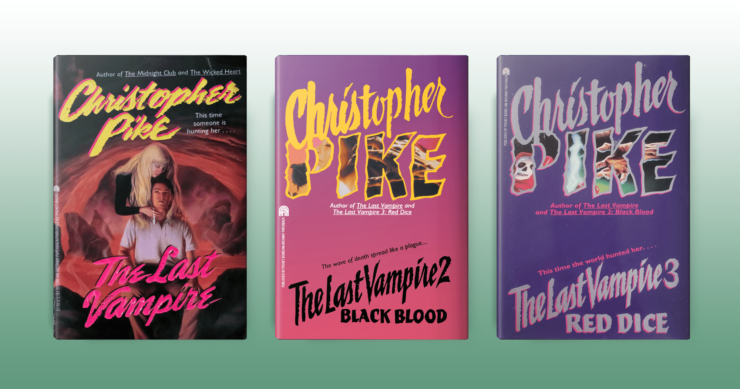

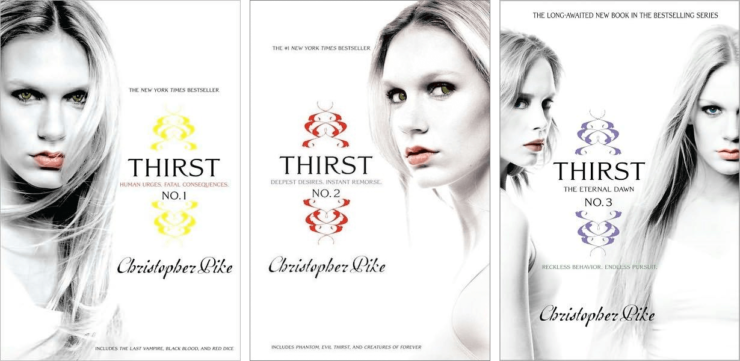

First, let’s establish our roadmap. Following 1994’s The Last Vampire, Pike’s 1990s Last Vampire series novels were The Last Vampire 2: Black Blood (1994), The Last Vampire 3: Red Dice (1995), The Last Vampire 4: Phantom (1996), The Last Vampire 5: Evil Thirst (1996), and The Last Vampire 6: Creatures of Forever (1996). Pike returned to the series—now renamed Thirst—in 2010 with The Eternal Dawn, followed by The Shadow of Death in 2011, and The Sacred Veil in 2013. It gets a bit confusing here though, because Pike’s previous Last Vampire novels were republished in two collections, with Thirst No. 1 containing The Last Vampire, Black Blood, and Red Dice and Thirst No. 2 containing Phantom, Evil Thirst, and Eternal Dawn, so The Last Vampire 7: The Eternal Dawn is Thirst No. 3, which has no impact on the linear progression of the actual story but is definitely confusing and useful to know if you’re interested in reading the series.

There is also a startling difference in the covers between Pike’s 1990s Last Vampire series and the 2010s Thirst series, with Pike’s instantly recognizable brightly-colored ‘90s covers being replaced by a whole lot of white: a white girl, with white blonde hair, in white clothes, against a white background. Everything is so uniformly white that when Sita is shown from the side on the cover of The Sacred Veil, for example, it’s very difficult to tell where the whiteness of her shirt ends and whiteness of the background begins, creating an oddly disembodied effect. There are isolated pops of color: a coral pink for Sita’s lips, her blue eyes, and pastel hues for a calligraphy-style design that frames the title and each novel’s four-word tagline (“Reckless behavior. Endless pursuit.” “Tortured soul. Final judgment.” “Ancient secrets. Epic retribution.”). This stark minimalism is a striking contrast to the narrative-driven covers of Pike’s ‘90s books, which foreground the metaphysical and the monstrous, and taglines that hint more concretely at the story within (like Phantom’s “The monster might be an angel”) rather than the 2010s novels’ cryptic keywords. And while we all know better than to judge a book by its cover, in some ways, this is a very effective visual representation of the path Pike’s series takes forward.

First, that fleeting moment of queer representation in The Last Vampire. Sita tells readers that “I have had many lovers, of course, both male and female—thousands actually—but the allure of the flesh has yet to fade in me” (67). This is a promising moment, though Sita remains more focused on her current male love interest, Ray, who she believes may be the reincarnation of her dead husband Rama, and who she loves so much that she breaks her vow to Krishna in order to transform Ray into a vampire to save his life and spend eternity with him, despite the fact that she’s only known Ray for about a week. This eternity doesn’t last very long, however, as Ray dies in the very next book (Black Blood), and despite the fact that prior to transforming Ray, Sita hasn’t broken her “don’t make any more vampires” promise to Krishna in 5,000 years, she almost immediately turns another guy, FBI agent Joel Drake, into a vampire, even though he explicitly TELLS HER NOT TO. This raises some really troubling questions about consent, particularly because Sita views her immortality as a curse, which she is now intentionally inflicting upon someone who actively doesn’t want it. Like Ray, she has known Joel for only a few days. Sita doesn’t seem to have any particularly strong feelings for Joel (he’s not the reincarnation of anyone she loves, for example) and like Ray, Joel sacrifices himself as collateral damage in the larger vampire conflict, transformed at the end of Black Blood only to die in the very next novel.

The promising moment of queer representation in The Last Vampire ultimately comes to nothing, as Pike slowly backpedals over the next several hundred pages. In Phantom, Sita notes that “I have had few female lovers during my fifty centuries” (34), an aside that is sandwiched between her statement that she is not sexually attracted to her new friend Paula and that her lover Ray “certainly … now takes care of all of my sexual needs” (34). The heteronormative paradigm is reestablished, with Sita’s desire and fulfillment exclusively male-focused. This feels like even more of an intentional act of erasure when Pike reveals that Paula is the reincarnation of Sita’s old friend Suzama, who she met in ancient Egypt and had an intense connection with (though Pike goes out of his way to clearly state that this relationship is not erotic or sexual in nature either, despite some fleeting moments of physical contact that could be read romantically) and the fact that Ray is actually a projection/hallucination/figment of Sita’s imagination, so she’s seemingly finding this sexual fulfillment with a man who doesn’t actually exist. By The Shadow of Death, Sita describes herself as “primarily heterosexual” (394) and one of her most unsettling experiences when she ventures into Hell—where you’d assume there’d be plenty of other things to worry about—is a mysterious, monstrous woman who comes on to her and tells Sita that she’ll have to kiss her in order to make it across the unpassable chasm that lies before her. Sita is so horrified by this proposition that she literally decides she’d rather jump off the cliff. Sita spends most of the series preoccupied by, protecting, or lusting after traditionally masculine characters (Ray, Seymour, Joel, Matt) and the final book finds Sita side-by-side with her former lover Yaksha, though Yaksha’s body is now inhabited by the soul of his son Matt, who is also her lover, as she thinks about killing him to undo her vampire existence and return to her human life and her husband Rama. The queer potential of The Last Vampire not only goes undeveloped, but is actually undone to at least some extent, as Sita’s feelings of same-sex desire are marginalized and become depicted as predatory and exploitative in her encounter with the woman in Hell in The Shadow of Death.

Pike’s series follows a similar pattern when it comes to diverse representation as well. While in The Last Vampire, Sita has a well-developed and reciprocal relationship with Krishna, viewing him as a friend and an individual, as the series progresses, he instead becomes a symbol, a means to an end. Krishna represents Sita’s path toward enlightenment and salvation, and while there are still isolated moments of personal connection, such as when Sita speaks to Krishna in the moments following her own death and decides to return to Earth to save her friends at the end of The Shadow of Death, he becomes largely a blank slate onto which Sita projects her own understanding and negotiation of faith. Toward the end of the series, in The Sacred Veil, Sita’s understanding of Krishna is fundamentally transformed as she comes to the realization that Krishna is “inside me” (422) and while this is potentially an empowering internalization of faith, it can also be read as an act of erasure, that her own knowledge and desires are aligned with those of Krishna, that she can speak and act for him, even when many of her actions have gone against what he has asked of her. As readers, we don’t need to see or hear Krishna any more, because Sita will act and speak for him, having claimed the divine perspective.

Pike draws several religious traditions together around the shared idea of faith, which offers some unique opportunities for diverse perspectives, though this doesn’t end up amounting to much. For example, Krishna’s narrative is often presented in parallel with the Christian belief system, including Paula’s son John, who was mysteriously conceived and may be the incarnation of Jesus. Paula and Sita meet one another when they’re both pregnant: Paula is pregnant with her son John, following a vision at Joshua Tree National Park, while Sita is pregnant with a daughter she calls Kalika, named after Kali, the Hindu goddess of death, time, and change. While this shared experience of pregnancy initially brings Paula and Sita close, Sita distances herself from Paula when she discovers that Kalika grows at preternatural speed and is at least half-vampire, capable of great violence, and obsessed with claiming John (though all is not quite what it seems and Kalika is actually working to keep John safe in her own potentially destructive way). Sita and Kalika fight in their respective quests to protect John, with Kalika dying in the process, and while Paula and Sita remain friends throughout the rest of Pike’s series, there is a persistent distance between them. Paula moves around a good deal, not telling Sita where she and John are living; she is unsettled and frightened when Sita tracks them down, though she always welcomes Sita into their home when she appears. The possibility that John is an incarnation of Jesus is raised even before his birth, though beyond noting that some people might be pissed about a Hispanic Jesus—another potentially empowering diverse moment of representation—this line of the narrative doesn’t really go anywhere at all. John is mysteriously wise but often won’t talk to the grown-ups and spends most of his time obsessively playing a video game, which leaves the nature and transmission of this wisdom unfulfilled.

Buy the Book

Seasonal Fears

There is a teenage Indian girl named Shanti in The Eternal Dawn and The Shadow of Death who serves the group as a source of goodness and moral protection, right up until it turns out she’s possessed by Lucifer and has been sabotaging the group all along. Even when this possession is discovered, Shanti is not redeemed, because even before this possession, she was a bad person who hurt other people, intentionally disfigured herself, and performed necromancy, a willing partner rather than an unwitting infernal conduit, which transforms one of the series’ most complex and sympathetic non-white characters into a horrific, inhuman Other.

Then there’s Seymour, who I would argue is the most interesting character in The Last Vampire. He’s just a regular, nerdy guy, but he happens to have an inexplicable psychic connection with Sita, intuitively sensing her thoughts and feelings. While he’s not the romantic interest, Seymour is the one who comes through when it counts, driving out to the middle of nowhere with a set of clean clothes and asking few questions after Sita murders a bunch of enemy agents and finds herself stranded and covered in blood. Seymour becomes Sita’s friend and the chronicler of her life, writing stories about her adventures that he draws from their psychic connection. In reading the rest of the Last Vampire series, I really wanted Seymour to survive, to shift from a sidekick role into an impactful character, and to have a driving force and motivation that wasn’t just his hope of having sex with a hot vampire. Throughout Black Blood, Red Dice, Phantom, and Evil Thirst, Seymour remains firmly situated in sidekick/emergency contact territory. When Sita needs something and has no one else to ask, she can call Seymour and he always comes through for her. When she needs someone to talk to, he’s always there to listen, a willing repository who asks for nothing in return. He periodically asks Sita if she’ll have sex with him or turn him into a vampire, but he knows she’ll say no to both, so it’s more of a running joke between the two of them rather than an actual request. Seymour is killed in the final pages of Evil Thirst, and because she is unable to let him go, Sita finally makes him a vampire (though she still won’t have sex with him, much to his chagrin). Readers get a brief glimpse of vampire Seymour early in Creatures of Forever, but Sita almost immediately sets off on a solo adventure and vampire Seymour basically becomes inconsequential.

Except that nothing is quite what it seems. While all of Pike’s Last Vampire books are told from Sita’s first-person narrative perspective, in The Eternal Dawn, Pike reveals that the first six books are Seymour’s version of events, Sita’s story told through Seymour’s interpretation. While the foundation of Seymour’s narrative is based on his psychic connection with Sita, he has taken several creative liberties, embellishing the story and engaging in a bit of wish fulfillment. Sita never turned Seymour into a vampire. In reality, the two of them never even met in person until The Eternal Dawn, making Seymour’s relationship with Sita and his heroic acts a figment of his authorial imagination. This reframing is doubly damning: not only are all of Seymour’s adventures invalidated and relegated to the imaginary, but Sita’s first-person voice is co-opted and erased. With this reframing employed, in the first six books, Sita is not telling her own story – the experiences she recounts and the emotional growth she experiences are a projection, someone else’s version of how she should have responded, a narrative constructed for and by another person. As a result of Sita and Seymour’s psychic connection, Sita’s reality and Seymour’s narrative are largely aligned, but not completely, making for some tricky textual navigation in deciphering what really happened, a surprisingly existential quandary. But while Seymour’s heart is in the right place and his loyalty to Sita is almost absolute, the fact that Pike silences Sita’s own voice and revokes the right for her to tell her own story in the first six books through this reframing is unsettling and problematic.

Finally, while vampires remain central to the Last Vampire series, Pike’s books take all kinds of metaphysical twists and turns, collapsing mythologies and creating a hybrid science fiction/fantasy universe that is complex, entertaining, and at times inexplicable. There are crystals, spaceships, beings from other dimensions, snake people named Setians, time travel, body transference, a superhuman race called the Telar, a Telar/vampire hybrid called “The Abomination” (though his friends call him Matt), weaponized psychically gifted children, time paradoxes, a computer game that brainwashes its players, Nazis, and the use of hypnosis to recover lost memories (which once again dramatically reframe Sita’s narrative, as well as her understanding of herself and her long life). The past and present are frequently synthesized, with people Sita meets now being disguised versions of enemies from hundreds of years ago. While Sita begins her narrative independent and powerful, by the series’ conclusion she has ceded much of her leadership to Matt, her friend and love interest, who she repeatedly acknowledges is stronger and wiser than she is. The series ends with Sita’s confusion and indecision, as she reflects in The Sacred Veil that “I honestly don’t know what I’m going to do next” (441).

Pike’s The Last Vampire held such promise and felt like it was on the verge of opening some doors for representation of diverse characters. There were possibilities and the potential for telling old stories in a new way, a twist on the vampire narrative that would empower previously marginalized characters and give voice to otherwise silenced tales. But throughout the rest of Pike’s Last Vampire series, these promises came to nothing. While some of these promises simply failed to develop (like the potential significance of John as a non-white incarnation of Jesus), many were explicitly broken, such as the presentation of same-sex desire and the racialized Other as monstrous, the revocation of Sita’s authentic narrative voice in the first six books, and Sita’s increasing passivity. The Last Vampire series becomes less inclusive with each book, eschewing one opportunity after another to build on the potentially empowering foundation Pike laid in The Last Vampire, which feels like a particularly cruel betrayal. While it is a constant frustration that the majority of ‘90s teen horror predominantly tells the story of white, straight kids, it feels even more devastating to have the possibility for something more offered and then taken away.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.