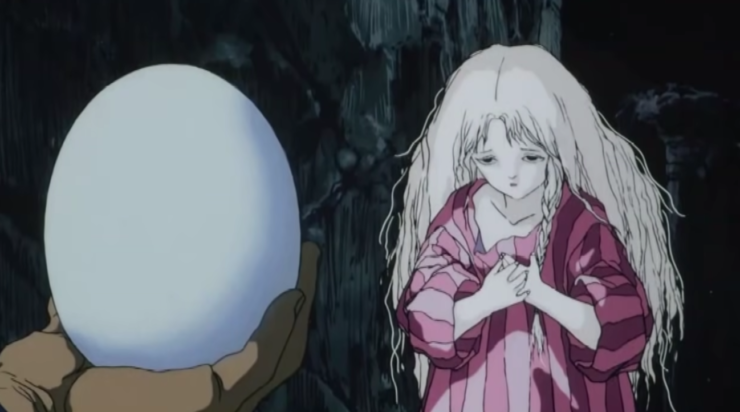

“What do you think is inside that egg?”

“I can’t tell you things like that.”

No story could be simpler.

We have a young girl, who at first appears to be pregnant, with a noticeable bulge under her rags, until she pulls out a rather large egg—maybe the size of an ostrich egg, maybe bigger. We have a man, perhaps a soldier or a mercenary, with a weapon that is inexplicably shaped like a crucifix; it could be a rifle, or a small cannon, but we never see the man fire this weapon. We have a city, or the remains of a city, its architecture a bizarre crossbreed between Gothic and steampunk.

Is this the distant future, or an alternate past?

Buy the Book

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak

The actual plot of Angel’s Egg, Mamoru Oshii’s 1985 direct-to-video film, is mind-bogglingly simple; it’s also hard to explain. We have a grand total of two human characters, neither of whom is named, plus a legion of mechanized (robots? statues?) fishermen. The young girl meets the man when the latter steps off what seems to be a self-operating machine—not a tank, but very unlikely to be this world’s equivalent of a taxi. The man offers to help the girl, to protect her as well as her egg, but what does he really want? What does he get out of this?

Angel’s Egg is a movie that’s hard to spoil, because so little happens plotwise that even with its scant 71-minute runtime, the pacing is what you might call “lethargic.” Really, it’s a mood piece—a dive into thoughts and emotions that are buried deeper than what a conventional narrative can probably tackle. The film was made early in Mamoru Oshii’s career, at a time when the most experience he’d had in animation was directing the first two movies in the romantic-comedy franchise Urusei Yatsura. Going from a wacky and fanservice-y series like Urusei Yatsura to Angel’s Egg has to be about as jarring a tonal shift in one’s career as you can imagine, but then Oshii is not known for being predictable.

When I watched Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell many moons ago (it’s still a go-to example of “mature” animation, which is like catnip for edgy teenagers), I was mildly intrigued but not entirely taken with it. I found Ghost in the Shell to be slow, gloomy, humorless, and generally not something you would put on for a night of drinking with the boys. Angel’s Egg is also slow, gloomy, humorless, and generally not something you would put on for a night of drinking with the boys. The key difference is that whereas Ghost in the Shell aspires to tell a story (albeit a loose one), Angel’s Egg places all its bets on visuals, music, tone, atmosphere, and symbolism. I have a soft spot for movies that ditch the three-act structure in favor of something more poetic, almost rooted in the id—offering a middle finger to pretenses of rationality.

The world of Angel’s Egg is undoubtedly post-apocalyptic; society as we know it does not exist. Not only is the dead and rotting city utterly barren, except for machinery that runs without human intervention, but the sun never shines. What kind of hellworld is this? How did we get here? We never get a clear answer. The young girl and the man never reveal their life stories to us; they remain these abstract figures, only existing because of their current emotional states, which themselves are often nebulous. The egg clearly means something to the young girl (she is rarely seen without it in her grasp), but we’re not let in on what significance the egg itself has. An easy answer would be that the egg (something inherently associated with birth) carries special weight in a world that is otherwise devoid of life, but I feel like this is reductive somehow.

A common interpretation regarding the egg is that it does not represent life or birth, but rather faith; indeed, Angel’s Egg (which already threatens us with incoherence) is rendered nigh-incomprehensible if you try to ignore its use of Judeo-Christian imagery. Never mind the man’s crucifix-shaped weapon, or the saint-like statues that stand in for what might have been the city’s populace, or the shadow-fish (as in fish that are literally shadows) which make their way through the streets and walls of buildings; this is a movie wading knee-deep in the Bible. The closest the movie comes to showing its hand in this regard is when the man (in what is by far the most dialogue-heavy scene) recounts what turns out to be the story of Noah’s ark—not just recounting, but in fact reciting lines from the Book of Genesis.

Is the man, then, out to protect the young girl’s egg (i.e., her faith), or to break it? We do get something like an answer, but that would be telling. That an egg, an object known for being fragile, should act as a stand-in for one’s faith is probably not a coincidence. I should probably mention that despite the plethora of religious symbolism, along with the straight-up text (not even subtext), this is not Christian propaganda. At the same time, it’s not a lazy, “religion bad” narrative, but rather it feels like a story told by a former believer who had lost his faith. Oshii is a rarity in Japan, in that he was raised Christian, and even considered entering a seminary, but not long before starting work on Angel’s Egg he would leave Christianity behind. He would, however, continue to read the Bible vigorously.

As someone who enjoys and watches anime regularly, I’m going to be blunt here and say that Christian imagery in anime is usually superfluous. At most, Christianity (if mentioned explicitly at all) is often relegated to a cultural curiosity—or Christian imagery might be used for the sake of aesthetics and not much else. Much as I love Hellsing Ultimate, I didn’t come out of it knowing any more about the Church of England than when I started that show. The relationship Angel’s Egg has with Christianity is so deliberate and so persistent, though, that it plays more prominently in the experience than what is (admittedly) naught but the bare bones of a plot.

The irony is that while Angel’s Egg puts more thought into religious symbolism than most of its ilk, it remains a unique aesthetic achievement. The character designs may ring a bell for older readers who grew up playing the older Final Fantasy games (IV and VI especially come to mind), since they were created by Yoshitaka Amano. Amano’s work on Angel’s Egg predates the Final Fantasy series, but he was already a veteran artist by 1985, and while his style is only featured noticeably with the man and young girl, these designs immediately lend distinctiveness to what would already be a feast for the senses.

You can enjoy Angel’s Egg as more of a pure audio-visual experience than as a movie, ignoring even the most obvious symbolism and instead choosing to revel in the gloomy but gorgeous animation, the haunting score by Yoshihiro Kanno, and the sheer feeling of desolation that the movie manages to convey without the need for dialogue—or even action. It’s a movie to watch in the dead of night, ideally by yourself, maybe when you’re not in the most optimistic of mindsets. Regardless of whether you take it at face value or put on your analysis hat, though, you’re not likely to forget it.

Brian Collins lives in some backwater town in New Jersey. He spouts nonsense on Twitter and contributes to the blog series Young People Read Old SFF.