Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

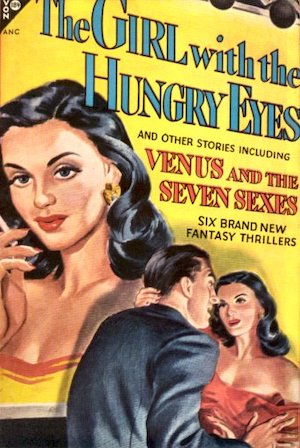

This week, we cover Fritz Leiber’s “The Girl With the Hungry Eyes,” first published in 1949 in The Girl With the Hungry Eyes and Other Stories. Spoilers ahead!

“You’re not fooling me, baby, you’re not fooling me at all. They want me.”

Our unnamed narrator, a photographer, tells a friend (or maybe just a friendly ear in a bar) why the Girl “gives [him] the creeps.” “The Girl” has replaced former advertising queens because she’s the complete package, the perfect sex icon to sell everything from cigarettes to bras. Narrator “discovered” her, but may be the only good American consumer who can’t stand to see her image on every billboard and in every magazine. For him, her trademark half-smile is poisonous. There are vampires and vampires, see, and not all of them suck blood.

There were those murders. If they were murders—no one can prove it.

Why does the public know so little about the Girl? You’d expect magazines to reveal her tastes and hobbies, her love life and political views. But no one even knows her name. Her pictures are all worked up from photographs taken by whatever damned soul is the only one who sees the Girl now, getting rich but “scared and miserable as hell every minute of the day.”

In 1947, narrator was working in a fourth-floor studio in a rathole building, nearly broke. Advertisers liked him personally, but his pictures “never clicked.” Then the Girl walked in wearing a cheap black dress. Dark hair tumbled around her gaunt, “almost prim” face, framing “the hungriest eyes in the world.”

Her eyes are why she’s plastered everywhere. They look at you with a hunger that’s “all sex and something more than sex,” the Holy Grail of sales bait. What narrator felt at the time, however, was fear and “the faintest dizzy feeling like something was being drawn out” of him.

Anyway, in a none-too-cultivated voice, the Girl asked for a job. She’d never modeled before but was sure she could do it. Impressed by how she “stuck to her dumb little guns,” narrator agreed to take some spec pics. He tested her resolve by posing her in a girdle, which she did unflustered. One smile was all he got in thanks for his efforts.

Next day he showed pix of the Girl to prospective clients. Papa Munsch of Munsch’s Brewery thought his photography “not so hot,” but the model was the Munsch Girl he was after. Mr. Fitch of Lovelybelt Girdles and Mr. Da Costa of Buford’s Pool and Playground were equally enthusiastic. Returning in triumph to his studio, narrator was horrified to find the Girl hadn’t left her name and address as requested. He searched everywhere from agencies to Pick-Up Row. Then on the fifth day she showed up and laid down her rules. She wouldn’t meet any clients, or give him her name or address, or model anywhere but his studio. If narrator ever tried to follow her home, they were through. Narrator ranted and pleaded; his clients protested. In the end, because they all wanted her badly enough, the Girl prevailed.

She turned out to be a punctual and tireless model, indifferent to the money she could command. Given how fast she caught on and how the money flowed in, narrator had nothing to complain about but the odd feeling of “something being shoved gently away.” His theory about her effect on people is that she’s a telepath who focuses the “hiddenmost hungers of millions of men,” seeing “the hatred and the wish for death behind the lust.” She’s shaped herself into the image of their desires while holding herself “aloof as marble.” But “imagine the hunger she might feel in answer to their hunger.”

Papa Munsch was the first client to go soft on the Girl. He insisted on meeting her, but the Girl, pre-sensing him in the studio, yelled to “Get that bum out of there.” Munsch retreated, shaken. Eventually narrator gave in to his own attraction. The Girl gave all his passes the “wet-rag treatment.” He grew “sort of crazy and light-headed.” He started talking to her constantly about his history; whether she even heard, he couldn’t tell.

About the time he decided to follow her home, the papers were running stories about six men who died without obvious cause, perhaps due to an obscure poison. Afterwards there was “a feeling [that the deaths] hadn’t really stopped but were being continued in a less suspicious way.” Trailing the Girl, narrator observed her picking up one man who admired her image in a store window, another while she stood opposite a Munsch Girl billboard. The second man’s picture appeared in the paper next day, another maybe-murder victim.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

That night narrator walked downstairs with the Girl. Unsurprised, she asked if he knew what he was doing. He did, he said, and she smiled, and though he was “kissing everything good-bye,” he had his arm around hers.

They walked in the park, silent, until she dropped to her knees and pulled him down after her. She pushed narrator’s fumbling hand from her blouse. She didn’t want that. What narrator did afterwards –

He ran away. Next day he closed his studio and never saw the Girl again in the flesh. He ran because he didn’t want to die. His dizzy spells, and Papa Munsch, and the dead man’s face in the newspaper all warned him in time.

The Girl, he concludes, is “the quintessence of the horror behind the bright billboard…the smile that tricks you into throwing away your money and your life…the eyes that lead you on and on, and then show you death.”

Here’s what she said to him in the park, along with a terrible litany of all the intimacies he’d gabbled at her seemingly unheeding ears: “I want you. I want your high spots. I want everything that’s made you happy and everything that’s hurt you bad… I want you wanting me. I want your life. Feed me, baby, feed me.”

What’s Cyclopean: The Girl, with her poisonous half-smile, is unnatural, morbid… unholy.

The Degenerate Dutch: Our photographer narrator scoffs at the idea of developing “long-haired indignation at the evils of advertising.”

Weirdbuilding: Nor is his paranoia about the Girl the sort of thing that “went out with witchcraft.” No Salem ancestors here!

Libronomicon: The Girl’s image appears in all the magazines. But no profiles, or gossip, or the slightest biographical detail.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Narrator may be off his rocker, suggests his unknown listener. But that’s okay, presumably, since he’s buying the high-quality whiskey.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

You know how Lovecraft created the perfect metaphor for nuclear war, presumably with some help from our favorite time travelers? Leiber seems to have mapped vampires perfectly to algorithmically-driven advertising—an impressive trick in 1949. Postwar marketers showed their hand early, I guess? At least to those looking closely.

Vienna Teng’s “The Hymn of Acxiom” gets it—the way targeted advertising is a form of sorcery, too intimate and too impersonal at the same time. The way it wants a relationship from you that it’ll never return, a parasite passing as a lover. Leiber describes the push toward conformity for the sake of commerce: “everybody’s mind set in the same direction, wanting the same things, imagining the same things.” And, intriguingly and horribly, the Girl is shaped by those shared desires. Dracula and Carmilla like to go after innocents and remake them in their own images; here it’s the ad-men forcing that predatory transformation.

Leiber, or maybe just his narrator, focus on the effect this has on the Girl’s prey: the millions of people—of men, one gathers—whose lives she yearns to suck up through her hungry eyes. But what about her? She remains alive, sure. But why does her hunger take that particular form? If she’s shaped by that million-strong monster of male desire, what happened to whatever she was before? Maybe she’s hungry for lives because she no longer has one of her own. Maybe her name and other biographical details aren’t merely secret, but non-existent.

Who wins, from her feeding? Not the men whose hearts give out, and certainly not her with her lost identity and unsated hunger. Only the forces profiting from her image, and from the consumers enthralled by it. Sound familiar?

I wonder whether this came through to most of Leiber’s original readers, or whether they just saw another story of a femme fatale. The mix of sex and death would hardly be unfamiliar; sex and death and advertising copy might have been less obvious.

On the other hand, sex and death and art are also a longstanding combination. Or sometimes just death and art. Advertising is a sort of corruption of the power that good art can have over our minds. Leiber’s narrator is a materialistic Pickman, torn between fascination with his subject and the need to make a buck, miserably trying to serve both those lures. Sordid monetary considerations, alas, don’t protect him from fantastical revelations.

Leiber’s story suggests two sorts of horror not actually in conflict: those revelations regarding the truth of the universe in which we live, and the tissue-thin veneer of lies that society pastes over them. If that veneer is itself designed to help unholy forces feed on our souls, it can hardly be preferable to looking on those forces directly. Once the algorithm gets its claws into you, even denial is no salvation.

Better go shopping while you can. Just be careful, when you run your credit card or fill out that survey, who you tell about your highs and lows, your shiny bicycle and your first kiss and the lights of Chicago and your wanting. Something is listening. Something is hungry. Something is ready to feed.

Anne’s Commentary

Along with “Smoke Ghost” (1941), “The Girl with the Hungry Eyes” (1949) hands-down establishes Fritz Leiber as one of the first great writers of urban horror. All the horrors sprung on humanity from Pandora’s box—physical disease and such perturbers of mind and character as resentment, anxiety, greed, callousness and unwonted aggression—are by that mythological definition ageless, but hasn’t our industrialized and city-centered life intensified them? A strong argument in favor of the proposition is that the wonders of modern communications technology, now commonplace, have so amplified our awareness of the “bad news” side of life that we feel singularly plagued by it? So plagued that we (Leiber, anyway) have to invent new monsters like a garbage-bred soot-faced god and a psychic vampire of a pin-up girl?

Leiber’s bete noire among the features of modern culture seems to be advertising. Catesby Wran, the protagonist of “Smoke Ghost,” is an adman. The narrator of “Girl with the Hungry Eyes” is the last person who should display “long-haired indignation at the evils of advertising” because he’s part of that whole “racket.” Truth: I looked back over Leiber’s biography to see if he ever worked in the ad game, but no, his animus doesn’t come from professional experience. “Girl’s” photographer depends on pushing products, but he’s a reflective kind of guy. Modern advertising, he figures, tries to standardize people’s mindsets and desires, tries to get everybody “imagining the same things.” That aim may be degrading in itself. It may also be dangerous. What if telepaths are real, and one of them is this girl who, perceiving the “identical desires of millions of people,” shapes herself into the epitome of those desires? What if she sees “deeper into those hungers than the people that had them, seeing the hatred and the wish for death behind the lust”?

What if, either being by nature a predator or being twisted by other hungers into a hunger of her own, the girl decides to consume her consumers? Or what if she’s been hungry all along, and modern advertising simply gives her appetite a nationwide and even global scope? Let her be ubiquitous and homogenized, owned by all in reach of billboards and magazines and newspapers, and who in the world isn’t? Not many people anymore—hell, they even have billboards in Egypt, and the Girl plastered on them! The Girl doesn’t need a life of her own, a name, an address, family, friends, hobbies or opinions. She lives on the lives of others, their emotions and memories, their most intimate experiences. Forget about blood, that’s small time vampirism when one’s stolen sustenance can be the contents, the energy entire, of your victim’s psyche.

Your victim’s superphysical entirety. Your victim’s soul.

The Girl exploits the power of advertising, of broadly cast media, but with her hunger for every detail of her objects’ lives, she also makes me think of someone addicted to celebrity journalism and “reality” entertainment. A pathological superfan! Only she doesn’t have to wait for the next issue of People or the next episode of Real Housewives. She goes right to the source.

I’m a fan of weird fiction about artists in general and about artists and their models in particular. Leiber’s stellar contribution to the sub-subgenre seems to lovingly borrow its structure and tone from Lovecraft and “Pickman’s Model.” Both stories are told by first-person narrators addressing a specific friend, one intimate enough to be trusted with “quite a story – more story than [he’s] expecting.” Both the auditors have (however jokingly) called one of the narrator’s “prejudices” a bit crazy. Lovecraft’s Thurber refuses to ride the subway. Leiber’s photographer can’t stand to see images of the Girl or witness the way “the mob” slavers over them. Probably detecting genuine concern in their friends’ insinuations, both narrators unburden themselves with an impulsive thoroughness of detail that betrays obsessive rumination over their terrifying experiences and lingering dreads. And the voices of the narrators, their respective colloquialisms, are a joy.

Oh, and in both stories, the models are first photographed and then “worked up” into drawings and paintings. Pickman’s models, I suppose, were too squirmy to pose for long. The Girl could probably have posed long and still enough to be drawn or painted, but could any artists have focused on her that long without passing out from her psychic sipping of their energies? That relatively mild predation might be involuntary. The Girl can control her “withdrawals” to some extent—the photographer feels faintly dizzy in her presence, but he also has a sense of “something being shoved away gently.” That something being the free flow of his life force to the Girl?

Oh yeah, our pic-clicker is right. There are vampires and vampires, and we’ve just begun to plumb their dark and seductive variety!

Next week, we continue Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, Chapters 9-10, in which we find out whether doctors can diagnose vampiric obsession.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.