“The most difficult performance in the world is acting naturally, isn’t it? Everything else is artful.”

—Angela Carter, from “Flesh and the Mirror” (collected in Burning Your Boats)

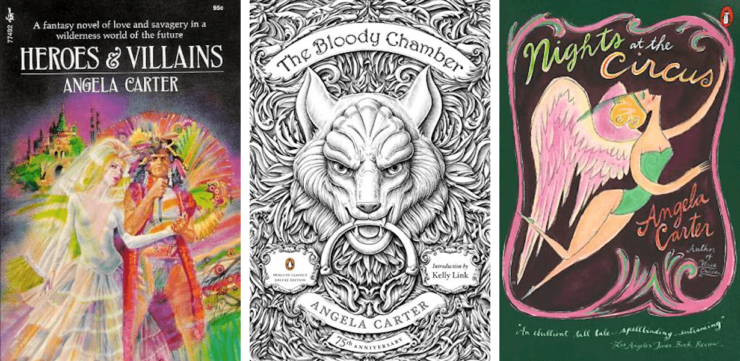

Angela Carter may be best known among fans of SF and fantasy for The Bloody Chamber (1979), her collection of feminist reimaginings of fairy tales, but her entire oeuvre is bursting with explorations of the SFnal, the gothic, and the fantastic. Though Carter is rightly regarded as one of the key literary authors of the 20th century, she should also be remembered as one of the era’s most adventurous and uncompromising fantasists. Even at her most realist, as in early works like The Magic Toyshop (1967), she is fascinated by the uncanniness of puppets and dolls, the spaces that the theatre opens up for the unreal to spill into our world, and the way that we can never truly know other people’s internal lives. Over the course of Carter’s more fantastical works, her flare for the gothic combines with surrealism and apocalyptic landscapes, folklore and fairy tales, the beautiful and the grotesque, to create a unique take on the fantastic that remains unmatched thirty years after her death.

Running through all her work is her incredible stylised command of language, her sharp wit, and her fierce engagement with feminist themes and ideas. Carter was equally at home with the novel and the short story, and also wrote a number of radio and screenplays, including the script for The Company of Wolves, the 1984 Neil Jordan film adaptation of the story of the same name from The Bloody Chamber. She was also a journalist and an insightful essayist, and her non-fiction is influential in its own right. But it is her novels and her short stories for which she is best known, and it’s her fiction that I would like to focus on for this essay.

Carter’s prose is exquisite. She excels at ornate descriptions, rich with sumptuous detail and symbolism. Yet she is rarely gratuitous; what is striking is how much detail she can conjure up with some choice descriptions, how she can instantly delineate character with a pithy observation. Nor does she descend into tweeness; she builds up visions of mythic grandeur only to puncture them with flatulence or bodily fluids, thus making sure the reader can never forget the lived experience of embodiment. For Carter, the mythic and the fantastic become an arena where our inmost desires struggle against our “civilised” selves, destroying the boundaries between reality and dream in the process. Her work can be as mind-bending as that of Philip K. Dick, as wise as Ursula Le Guin, as sensual as Kate Bush. Here are some of her most fascinating science fictional and fantastical works, ripe for exploration by lovers of genre fiction.

Heroes and Villains (1969)

On the wall outside the Doctor’s room was written up: OUR NEEDS BEAR NO RELATION TO OUR DESIRES. He let it stay there for several weeks.

“But how can one tell which is which,” Marianne asked herself and thought no more about the slogan. [89]

Heroes and Villains is the first of Carter’s novels to sit explicitly in the realm of genre fiction—it is a post-apocalyptic novel. Yet Carter’s first foray into the genre bears more in common with the psychological landscapes of J.G. Ballard than with any more traditional take on the genre. The cause of the end of the world is never explained, instead jumping straight into exploring how the apocalypse creates a new venue for the mythic.

The novel is set in a world in which the survivors are divided into the Professors, privileged academics who live in the remains of the cities, and Barbarians, who live in marauding tribes in the jungles beyond. The protagonist, Marianne, is the daughter of a Professor who grows bored of the safety of her father’s enclave and is captured by Jewel, a Barbarian, to be his bride. What follows is an erotic struggle, as Marianne and Jewel battle with each other and their newly awakened desires across a world where civilisation is fading and nature is reclaiming the planet.

The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman (1972)

“His main principles were indeed as follows: everything it is possible to imagine can also exist.” [112]

The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman is perhaps Carter’s most brilliantly deranged creation. The novel is set in a South American city where reality itself is under attack by Doctor Hoffman and his mysterious machines, which are making people’s dreams a reality. The resulting chaos is barely contained by the strenuous efforts of the Minister of Determination, who in desperation sends his best man, Desiderio, to assassinate the Doctor. Unfortunately, Desiderio’s fate is already tied to the Doctor’s beautiful daughter Albertina, who is made of glass and has been visiting him in his dreams.

Desiderio’s quest to find Albertina and Doctor Hoffman leads him through a surreal landscape involving carnival peep shows, pirates, and centaurs. Doctor Hoffman is in the process of rewriting the world in his own image, and Desiderio ultimately has to decide between his greatest, most passionate desires and saving reality itself.

Fireworks: Nine Profane Pieces (1974)

The puppeteer speculates in a no-man’s-limbo between the real and that which, although we know very well it is not, nevertheless seems to be real. He is the intermediary between us, his audience, the living, and they, the dolls, the undead… [47]

Though perhaps not as iconic as The Bloody Chamber, Carter’s first short story collection Fireworks: Nine Profane Pieces demonstrates her mastery of the form and her love of the strange and fantastical. In the afterword, she states, “I’d always been fond of Poe, and Hoffman – Gothic tales, cruel tales, tales of wonder, tales of terror, fabulous narratives that deal directly with the imagery of the unconscious” [549]

The stories in Fireworks, written after her divorce and a two-year stint in Tokyo, bear out this fondness. In “The Loves of Lady Purple,” a puppet master’s most beloved puppet is brought to life by the stories he tells about her; he grows frail and weak as she grows more and more real, eventually killing him. “Penetrating to the Heart of the Forest” retells the story of the Garden of Eden in a forest full of monstrous vegetation. “Reflections” involves a journey through the looking-glass into a world of sexual violence. Other stories deal with Carter’s experiences in Japan and the loneliness of her divorce, but even these more realist stories are full of recurring images of mirror doubles, puppets and their masters, flowers with hidden teeth. The fantastic encroaches on the real in order to draw thematic parallels across Carter’s stories, between her magical fantasies and her lived experience, with each heightening the other.

The Passion of New Eve (1977)

“Here we were at the beginning or end of the world and I, in my sumptuous flesh, was in myself the fruit of the tree of knowledge; knowledge had made me, I was a man-made masterpiece of skin and bone, the technological Eve in person.” [142]

The Passion of New Eve is Carter’s most challenging and fraught exploration of gender, telling the story of Evelyn, a young Englishman who abuses and abandons the woman he has impregnated. Fleeing to the desert, he is captured by a matriarchal cult and surgically transformed into a woman, Eve.

The novel’s portrayal of transition as sexual violence is deeply problematic, but Carter’s sympathetic portrayal of a trans character was progressive in the context of second-wave feminism of the time. And The Passion of New Eve is a book that explores the malleability of gender, as well as the ways in which gender is performative. Gender and sexuality are key themes for Carter, and nowhere is this more evident than in this novel, in which the conflict between men and women is literalised into a post-apocalyptic war of the sexes that has swallowed the USA, where both masculinity and femininity are aspects of how the heterosexual matrix props up the patriarchy. The Passion of New Eve is a harrowing exploration of sexual violence, unflinching in its portrayal of how damaging restrictive understandings of gender are.

The Bloody Chamber (1978)

What big teeth you have!

She saw how his jaw began to slaver and the room was full of the clamour of the forest’s Liebestod but the wise child never flinched, even when he answered with:

All the better to eat you with.

The girl burst out laughing; she knew she was nobody’s meat. [138]

The Bloody Chamber is Carter’s reimagining of fairy tales through a feminist lens, and possibly her best-known and best-loved work. Although in many ways it’s a less radical text than The Passion of New Eve, its retelling of familiar fairy tales in ways that return agency to the female characters remains powerful and affecting.

The title story is a reworking of “Bluebeard” in which the patriarchal violence of Bluebeard is destroyed by a daughter’s bond with her mother. “The Courtship of Mr Lyon” and “The Tiger’s Bride” are both compelling takes on “Beauty and the Beast,” upending the Beast’s dominance over Beauty whilst exploring the surrender to animal lust. “The Lady of the House of Love” is a vampire story in which the feminine wiles of the vampire will not destroy the masculine hero, but the orgy of masculine violence of the World War he is about to go off and fight in will. The three wolf stories, “The Werewolf,” “The Company of Wolves,” and “Wolf-Alice,” act as a series of kaleidoscopes through which the story of Red Riding Hood, the Wolf, and the Hunter are dissected to explore and subvert the sexual undertones of the original tale. Carter expertly links the stories through recurring phrases, images, and symbols, which highlight how the different tales and their different treatments repeat and recontextualise familiar ideas and tropes.

Nights at the Circus (1984)

“Oh, my little one, I think you must be the pure child of the century that just now is waiting in the wings, the New Age in which no women will be bound down to the ground.” [25]

Nights at the Circus is the story of Sophie Fevvers, the Cockney Venus, aerialiste extraordinaire who sports an elegant pair of birds wings and was hatched from an egg. A smash hit across Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, not everyone believes Fevvers is what she claims to be. Jack Walser, a cynical American journalist tries to uncover the truth behind her fantastical life, but his obsession with Fevvers sweeps him up and soon he is joining Colonel Kearney’s circus to follow Fevvers on her tour across London, St Petersburg, and Siberia.

The larger-than-life Fevvers is one of Carter’s most enduring characters. In the end it does not matter if she is for real or a fraud: A fat woman from a working-class milieu raised by sex workers, she has the wings of an angel but is utterly practical and down-to-earth, and her incredible charisma and wonderfully realised voice carry the story. Carter takes us on a delirious tour through Europe and Asia in a narrative that draws from a wide range of fairy tales and revels in the theatricality of the circus. Comical set-pieces and strikingly bizarre supporting characters abound. Through her sheer force of personality, Fevvers rises up again and again against a society that frequently casts her as monstrous because of her gender, her class, and her body type, yearning towards the freedoms and the horrors in store in the coming twentieth century.

***

Carter is a writer whose work is infused with the mythic and the surreal, who takes fairy tales and speculative fiction scenarios and twists them to her own end. Her interest in the space between theatricality and performance and the real and everyday mean that she is constantly interrogating the boundary between dream and reality, symbol and symbolised. This ensures that even her less fantastical work can seem fantastical in the right light. The interweaving of Shakespeare’s plays and fairy tale motifs in Wise Children (1991), or the sinister parallels between the protagonist’s enclosed existence and her abusive uncle’s lifelike dolls in The Magic Toyshop take on extra resonance and uncanny power.

Just like the audience at the circus gazing in wonder at Sophie Fevvers’ majestic wings, whether or not we are looking at a woman with angel’s wings or a fraudster is less important than the sense of encountering something strange and numinous. Carter’s bold and challenging engagement with the tropes of fairy tales and fantastic fiction serve as a vivid, lasting reminder of just how strange and uncomfortable these familiar tools can become in the right hands.

Jonathan Thornton has written for the websites The Fantasy Hive, Fantasy Faction, and Gingernuts Of Horror. He works with mosquitoes and is working on a PhD on the portrayal of insects in speculative fiction.