There is a distinct element of mystery and suspense that permeates much of 1990s teen horror (and the genre as a whole, for that matter). Characters run around trying to figure out who is sending cryptic notes or making creepy phone calls, or working to determine the identity of the dark figure lurking in the shadows, the face hiding behind a mask. While these dangers are unnerving and often create a sense of uneasiness for the characters being targeted, surveillance and stalking are their own unique subset of terror.

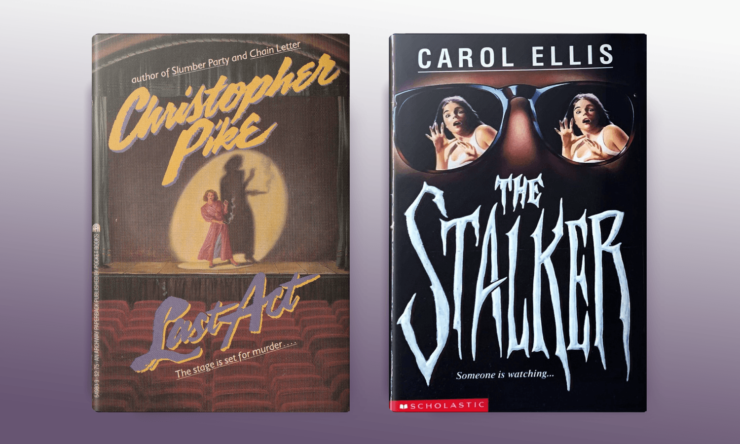

In Christopher Pike’s Last Act (1988) and Carol Ellis’s The Stalker (1996), the novels’ respective heroines are performers, in a position where they expect and even enjoy being looked at, though some of the people who watch them take this voyeurism to threatening levels, not content to stop when the curtain falls.

In Pike’s Last Act, Melanie is an actress in her local high school play and in Ellis’s The Stalker, Janna is a dancer in a traveling theatre company. Both Melanie and Janna are new to their positions, so in addition to learning their roles, they’re also figuring out where they fit in with the larger group: Melanie is the new girl in town and has struggled to get to know many of her peers, which makes the play an excellent social opportunity, while this is Janna’s first summer with the touring company, where she is joining several actors and crew who have traveled with the group in previous seasons. As a result, these two girls’ identities are particularly performative in nature, as they play their roles on stage, while also trying to figure out who they want to be and how they want others to see them within the context of these new experiences and opportunities.

Pike’s Last Act presents a unique scenario: a girl named Susan writes a play whose driving action mirrors the social dramas and conflicts of her peer group, pretends that play was written by another person and she just happened to “find” it, and then has her friends perform it, in the hope of getting vengeance for a terrible car accident that paralyzed their friend Clyde and for which Susan holds Clyde’s girlfriend Rindy responsible.. This is obviously a perfectly reasonable, straightforward way of solving one’s problems and much more effective than conversation, conflict resolution, or therapy. The play is called Final Chance, reflecting Susan’s warning, but no one picks up on it. The play, set immediately after World War II, is an odd and potentially grandiose choice for Susan’s transference of her clique’s social drama, given that a devastating car crash really isn’t the same thing as losing a limb due to a combat-related injury, and that the adolescent turmoils of Susan’s friends aren’t all that analogous to the concerns and stressors of a bunch of married adults. Susan attempts to explain her creative process and rationalization of these parallels in her final confrontation with Melissa and Clyde, but they really don’t make much sense to anyone other than Susan herself.

Buy the Book

Nona the Ninth

Susan is always watching her friends, projecting her own meanings and interpretations onto their actions and crafting narratives that affirm her own perceptions and biases. After the wreck, Susan lays all the blame on Clyde’s girlfriend, Rindy. She refuses to believe that Rindy wasn’t driving (even after Clyde tells her so) and insists that Rindy is a bad influence, telling Clyde: “She used you! She was no good!” (205). Even when Clyde has laid out all of the evidence in Rindy’s defense—that she supported him, wouldn’t allow him to drive drunk, and lied to protect him—Susan still desperately clings to her own version of events, where Rindy is the villain and Susan’s the right girl for Clyde, the only one who really “sees” him for who he is, oblivious to the fact that what she “sees” is actually a figment of her own imagination and projection.

When Susan directs the play, all she is really doing is formalizing a process of voyeurism and manipulation that she engages in with her friends on a daily basis. In her writing and casting, she transforms her peers into character types: Clyde becomes the damaged romantic hero, Rindy becomes the “bad girl” who must be killed, Susan’s proxy becomes the avenging heroine, and so on. However, Susan’s manipulation takes a fatal and exploitative turn, as she gets the unwitting Melanie to play her part and shoot Rindy onstage during a live performance. The idea of a high school production using a real gun (actually, two real and identical guns once the hijinks really get underway!) seems ludicrous and Pike does note that the PTA sure isn’t happy about it, but they didn’t find out until opening night, so apparently there’s nothing they can do about it (which seems unlikely, and also why is there no other adult oversight at any point in the process?). Melanie pulls the trigger as rehearsed, kills Rindy as Susan planned, and in a rare instance in ‘90s teen horror, actually faces real legal repercussions as a result of her actions. She’s taken into custody, held in jail overnight, and has to hire a defense lawyer and attend a pretrial hearing. While in the vast majority of these novels, the culprit is apprehended and fades into the shadows (usually juvenile detention, punitive boarding school, or a mental institution), Pike devotes the whole second half of the novel to the fallout of Rindy’s murder, with particular focus on what the criminal justice system process looks like for Melanie (who is eighteen and will be legally tried as an adult) and how Rindy’s friends process their shock and grief in different ways, engaging with the aftermath of this traumatic violence rather than focusing exclusively on the murder itself.

In the end, Susan is tricked into confessing by Clyde and is arrested, but not before the school lets her put on the play again (bad idea), with Susan in the role she had modeled after herself (really bad idea), while recasting Melanie as the character who gets murdered (did I mention this is a bad idea?). Susan has crafted a story for herself—both on the stage and in her real-life interactions with her friends—and refuses to revise it even when Clyde attempts to reason with her. She is willing to sacrifice anything and anyone as long as she can keep believing the narrative she has told herself and has forced her friends to perform on the stage.

(Last Act also gets an honorable mention for oddest and most inexplicable literary reference shout-out, for its allusions to J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Salinger’s novel is beloved by a wide range of angsty teens who feel like the world just doesn’t understand them and in Last Act, Rindy—who remains largely undeveloped otherwise—is philosophically obsessed with the question Holden Caulfield ponders of where the ducks go in the winter, with Rindy wondering about the local reservoir’s own waterfowl. Pike uses this literary allusion as a shorthand to let readers know there’s more to Rindy than meets the eye, but never actually delivers on what that “more” is. The group’s wild friend Jeramie likes to swim with the ducks and also shoots one, making the ducks a pretty messy mixed metaphor. These ducks are part of the closure offered at the end of the novel as well, when Melanie and her new friends discover what happens to the ducks in the winter, which is that Sam, the owner of a local diner, goes out in a boat, collects the wild ducks, and keeps them in his barn over the winter, releasing them again in the spring. This is preposterous. This is not how ducks work).

Ellis’s The Stalker follows a more traditional narrative of voyeurism and stalking, as Janna is tailed by a fan who is obsessed with her when she plays a random chorus dancer in a regional theatre company’s traveling performance of Grease. What starts with notes of admiration and flowers turns into threats, window peeping, attempted murder (first by drowning, then by vehicular homicide), and the destruction of one very unfortunate teddy bear. While Janna is initially flattered by the attention and loves being asked for her autograph after shows, she quickly becomes unnerved and terrified as the stalking behavior escalates and she fears for her safety and her life.

What complicates matters in The Stalker is that there’s a whole lot of intersecting problematic behavior going on, which makes it hard for Janna to tell who the real threat is and exactly what she has to fear. She has a possessive ex-boyfriend who didn’t want her to join the theatre company and calls to threaten her and demand that she come back to him, even showing up in one of the towns on their tour. There’s a devoted fan named Stan, who follows Janna and the show from town to town, tells her how much he loves her, sends her flowers, peeps in her hotel room window, and follows her and some of her fellow actors home one night. There’s a crew member who’s infatuated with Janna and has a hard time taking no for an answer, even after Janna clearly defines her boundaries and explicitly asks that he respect them. A rival actress named Liz works to undermine Janna’s confidence and sabotage her performances. All of these behaviors are problematic on their own, though none of these individuals turn out to be the person who is trying to kill her. So not only does Janna have to worry about surviving the attentions of the stalker who is trying to murder her, there’s a whole cast of characters who are also threatening and potentially dangerous, reasserting the dominant worldview in ‘90s teen horror that the world simply isn’t a safe or welcoming place for young women.

Janna is surprisingly proactive in responding to the dangers she faces, running outside to try to figure out who’s calling her from the nearby phone booth and tackling Stan when he follows her and her friends and it looks like he might get away from the cops. She refuses to cower in fear and takes action to protect herself when she realizes she can’t count on anyone else to do it for her. As a result, she is criticized by her friends and the authorities for being impulsive and irresponsible, has her every choice critiqued and second-guessed, and is told she is overreacting and hysterical when she defends herself, calls people out for their problematic behavior, or attempts to assert her own boundaries in her interactions with them. When she doesn’t take action, she is victimized—but when she does take action, she’s seen as “crazy.” Even when Janna is doing exactly what she needs to do to protect herself and stay alive, she can’t win.

When the stalker’s identity is finally revealed, as in Last Act, Janna’s attacker is another young woman: in this case, Stan’s girlfriend Carly. Janna has, for the most part, been expecting the threat to come from the men she has encountered: her ex-boyfriend, her ardent fan, her potential love interest. (There has been some professional jealousy with Liz, but nothing that has really put her in serious contention for stalker suspicion.) Janna has had no interest in Stan and is not a romantic rival for his affection, but Carly blames Janna for Stan’s obsession rather than holding Stan himself accountable, and has decided that Janna needs to die. She pushes a huge chunk of the set over on Janna as she practices, tries to drown her, attempts to run her down with a car, and, finally, locks her in the theater and chases after her, attempting to beat Janna with a length of chain attached to a piece of pipe (perhaps an unconventional murder weapon of choice, but presumably easy to get and incredibly effective).

In both Last Act and The Stalker, the violence occurs between girls, driven by the most heteronormative of motives: a crush on a cute boy. In both cases, the girls committing these assaults are shown to be psychologically unbalanced and incapable of rational thought, driven to violence by their inability to get a handle on their emotions or their romantic desires. Interestingly, neither of these girls are killed at the end of their respective novels: Susan is taken into custody after the police use a teenage boy as an unofficial hostage negotiator and Carly is seriously injured after a fall from the theater’s catwalk as she chases Janna. In both cases, the girls who have been threatened express empathy and pity for their attackers once the immediate danger has been neutralized. Last Act’s Melanie even expresses relief that since Susan is seventeen, she won’t be tried as an adult (even though Melanie herself was very nearly tried as an adult for a crime orchestrated by Susan). Despite the horrors for which they are responsible, in their novels’ final pages Susan and Carly are seen as sad, misguided, pitiable young women, denied even the possibility of being compelling villains as their actions are explained and dismissed as feminine hysteria, just the kind of thing you would expect from a “crazy girl.”

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.