Although it was fifty-five years ago, I have distinct memories of a special movie night hosted by my grade school in Waterloo, Ontario. On that night, my school played a remarkable double bill that made it clear that parents and teachers felt their kids could be a lot more traumatized than they currently were.

There have been a fair number of children’s films that may well have featured prominently in children’s nightmares. Here are five of my favourites, not all of which are SF or fantasy-related.

There will be some spoilers—also, some descriptions of bad things happening to animals and children, if you’d prefer to preempt any potential trauma. And I’d like to say up front that none of these are ineptly made or exploitive films. They’re justly classics, even if not necessarily ones that you should spring on little kids without preparation and perhaps some post-movie consolation and reassurance.

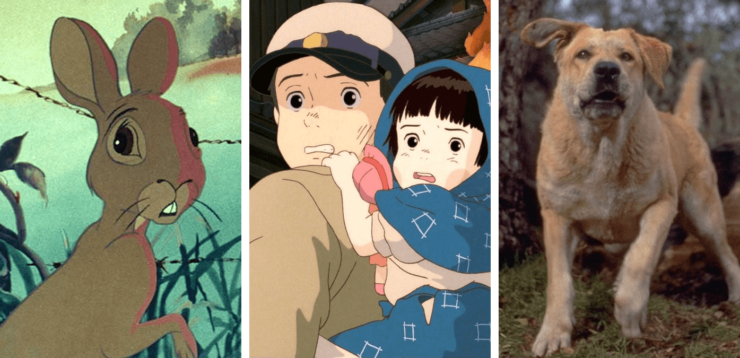

Old Yeller (1957)

This beloved Disney classic isn’t genre. I include it because it was the first of the two films shown on that fateful night back in 1967. Old Yeller is the touching story of young Travis and his faithful dog, the Old Yeller of the title. On a number of occasions, Yeller places himself in harm’s way to protect Travis. On the final occasion, the dog fights off a rabid wolf, raising concerns that Yeller may have contracted the disease.

It’s important to mention at this juncture that the audience was composed of children utterly unfamiliar with Death by Newbery. Most of us expected Old Yeller would be OK in the end. Old Yeller was not OK in the end. Old Yeller was rabid and Travis had to shoot his own dog. Which, granted, was more merciful than letting the dog die of rabies, but not at all the happy ending the audience of increasingly upset kids expected.

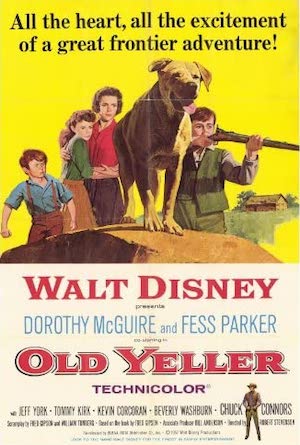

The Red Balloon (1956)

Albert Lamorisse’s fantasy was the second film shown that night. It features a Parisian boy who is befriended by a mute but seemingly sentient helium-filled balloon. Together, the pair have heartwarming adventures together in a Paris where World War Two is a recent memory. The red of the balloon provides a cheerful contrast to a city still rebuilding from total war.

If only the film were twenty-five minutes long and not thirty-five. Thirty-five minutes was long enough for its creator to realize there hadn’t been any sudden bereavements. Thirty-five minutes was long enough for a gang of jealous bullies to shoot down the balloon with slingshots before trampling it. There is a resurrection of sorts that follows, but I think we’re all agreed that the central lesson of The Red Balloon is that if something is precious to you, you should conceal it in a needle that is hidden inside an egg, within a duck, the duck hidden in a hare, locked in a chest buried on a remote island and never, ever mentioned to anyone.

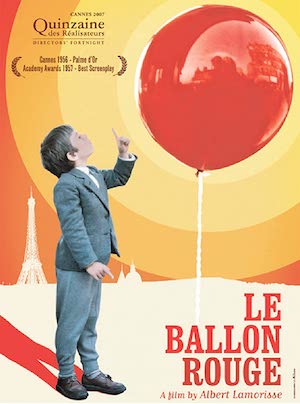

Watership Down (1978)

Based on the Richard Adams novel of the same name, the film depicts the struggles of a community of rabbits to survive and prevail despite a host of setbacks. Audience identification with the rabbits was facilitated by Adams’ rich vision of what rabbit culture might look like. Consequently, the host of characters are not merely animals whose fates are of no particular importance to viewers, but sympathetic figures about whom people will care deeply.

I would be inclined to cut parents who exposed their kids to this remarkable film some slack. After all, it appears to be a movie about cute rabbits? Who, aside from everyone who understands the implications of being small, crunchy prey in a world of predators, expects horrific tragedy in a film about cuddly bunnies? On the other hand, the movie poster above makes it pretty damn clear this isn’t your grandfather’s Peter Cottontail.

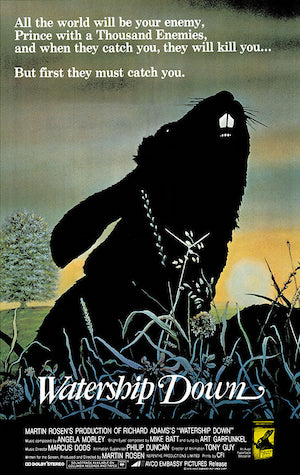

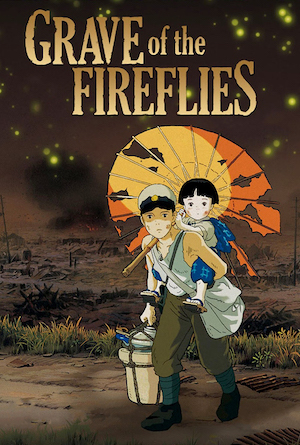

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Based on Akiyuki Nosaka’s 1967 semi-autobiographical short story of the same name, Studio Ghibli’s animated adaptation follows siblings Seita and Setsuko. Orphaned due to an Allied bombing raid during World War Two, the pair live for a time with their aunt. The aunt makes her displeasure at the cost of supporting the children clear. Offended, Seita takes his sister to live in an abandoned bomb shelter. This proves to be a fatal miscalculation. Now outside society, with no adult responsible for their well-being, the pair face slow death by malnutrition.

Grave is utterly relentless in the pursuit of its logic; the animation is magnificent and leaves little to the imagination. Given the premise (and the events on which the story is based), there was no way for it to end well. Still, watching two children starve to death because of misplaced pride is fairly unpleasant. Interestingly, this debuted in a double bill with the considerably more upbeat My Neighbor Totoro. I have always wondered what the kids in that first audience felt about their experience.

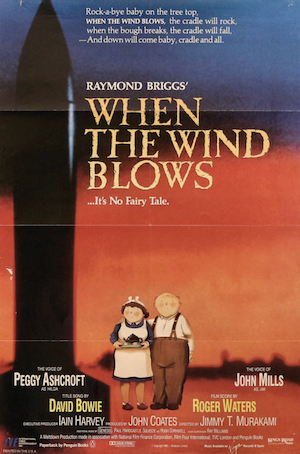

When the Wind Blows (1986)

This adaptation of the Raymond Briggs novel of the same name focuses on English pensioners Jim and Hilda Bloggs (based on Briggs’ own parents). As international tensions soar, the Bloggs faithfully follow advice in government-issued Protect and Survive pamphlets. Old enough to remember World War Two, the Bloggs are confident that a full-scale thermonuclear exchange will be much the same as the global conflict they lived through as children. This confidence is sadly misplaced.

Clearly, thanks to unfortunate current events, there are elements of the movie that remain relevant today—not least of which is the Bloggs’ determination, having survived the initial stages of the war, to return to normalcy regardless of whether returning to normalcy is a reasonable expectation.

I suspect that When the Wind Blows was never intended as children’s fare. However, a cultural peculiarity of the time—the perception that despite all evidence to the contrary, animated films were all intended for kids—ensured that the animated feature was shelved in the children’s section of video stores. What hilarity must have ensued as the final credits rolled.

***

While handing kids actinides in kiddie chemistry sets is now a thing of the past, I am certain this is not true for horrifying children’s movies. Feel free to name your favourite examples in the comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is eligible to be nominated again this year, and is surprisingly flammable.