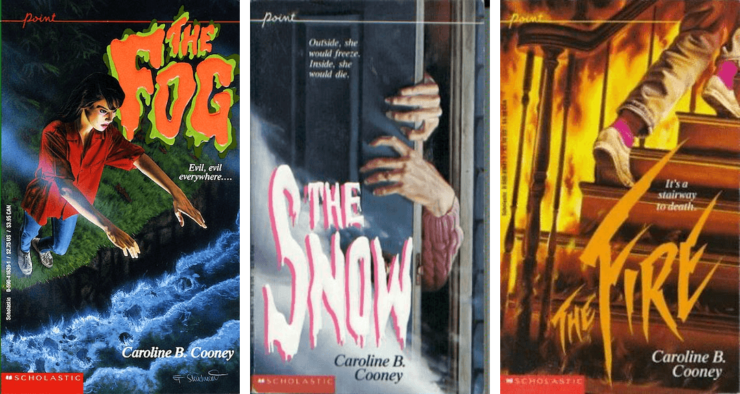

Caroline B. Cooney’s trio of novels of The Fog (1989), The Snow (1990), and The Fire (1990)—also known as the Losing Christina trilogy—was Cooney’s first horror series. Prior to The Fog, Cooney was particularly well-known for novels of teen romance and drama, including the high school dance-themed Night to Remember series (1986-1988). Following the Point Horror success of the Losing Christina series, Cooney became one of the main names in the ‘90s teen horror trend, with her Vampire trilogy of The Cheerleader (1991), The Return of the Vampire (1992), and The Vampire’s Promise (1993), as well as several standalone novels, including Freeze Tag (1992), The Perfume (1992), and Twins (1994).

Cooney’s Losing Christina series focuses on the misadventures of its protagonist, Christina Romney, a thirteen-year-old girl who is sent from her home on Burning Fog Isle off the coast of Maine to attend school on the mainland. Christina and several other teens from the island board with a couple named the Shevvingtons. Mr. Shevvington is the high school principal, Mrs. Shevvington is the seventh grade English teacher, and Christina becomes almost immediately convinced that the two of them are evil and on a mission to destroy the young women in their care.

Cooney’s series echoes the class consciousness and teen social dynamics that were central to many of the novels within the ‘90s teen horror tradition, though with a distinct regional flair. Christina and her island peers are vigilant in drawing distinctions between locals and tourists, and play to the tourists’ vision of quaint, romantic island life, though their mainland peers ostracize the islanders for this difference, viewing them as uneducated, backward, and even morally suspect. While Christina wears nondescript, practical clothing, the upper-middle class mainland teens are frequently described as wearing “Catalog Maine” fashions, like “a fine rugby shirt with wide stripes, high quality boat shoes without socks, and loose trousers made of imported cotton” (The Fog 7), clothes which are presented as both a bit ridiculous and a desirable status symbol. The two most popular girls in Christina’s grade, Gretchen and Vicki, befriend Christina for the express purpose of ridiculing and ostracizing her. The worst possible insult the mainlanders can level at the islanders is to call them “wharf rats,” a socially-coded denigration that implies a lifetime of drudgery, dropping out of high school, teen pregnancy, and losing all of one’s teeth.

Buy the Book

Dreams Bigger Than Heartbreak

Despite the novels’ incorporation of contemporary teen fears and anxieties, there is something almost timeless about the horrors Christina endures. Christina, for example, can be read as a modern-day Isabella from Horace Walpole’s Gothic classic The Castle of Otranto (1764), alone in a hostile fortress—in this case, the historic house of a sea captain that has now been repurposed as the Schooner Inne—and driven by desperation to the tunnels that lie beneath. For both Isabella and Christina, the threats they face are unrelenting, with these young women at risk of losing both their bodily safety and their sanity, as their abuses are allowed to run unchecked while they search desperately for an ally. The multiple staircases within and tunnels beneath their respective prisons fail to offer any promise of safety or escape, but their repeated navigation of these labyrinthine spaces provides an effective symbol of the unspoken psychological and sexual horrors each heroine finds herself up against.

While Christina begins telling people that the Shevvingtons are evil and mistreat her almost as soon as she begins boarding with them, no one believes her. Her fears and concerns are dismissed as Christina “yarning,” which is colloquial Burning Fog Isle-speak for telling tall tales. Some of the things she complains about—such as not liking the food the Shevvingtons serve or being relegated to the attic rather than offered one of the inn’s guest rooms—could reasonably be chalked up to an adolescent girl struggling to adjust to her new surroundings and reconcile her daydream expectations of mainland living with the less glamorous reality. However, those she turns to for help are just as quick to dismiss Christina when she complains of Mrs. Shevvington singling her out in class and publicly shaming her in front of her peers, the Shevvingtons’ abuse of another island girl named Anya, and someone pushing Christina down the stairs in the Inne and out of a chair lift while on a ski trip. The Shevvingtons tell people that Christina is simply unbalanced, attention seeking, and a liar, and everyone believes them, even Christina’s own parents.

There are witnesses to many of these interactions, though Christina’s peers stay silent either out of fear or their own cultivation of good will with the Shevvingtons, backing the adults’ version of events to save themselves from becoming the next victim. Christina also identifies a track record of other girls the Shevvingtons have abused, including Val, who is the sister of one of Christina’s classmates and institutionalized at a nearby mental facility. As her case against the Shevvingtons grows, they go to greater lengths to discredit Christina, continuing to convince people that she is mentally ill and even framing her for attempted theft and arson. Though Christina continues to speak out, the Shevvingtons are respected public figures, seen as “good” people, and first and foremost, are adults whose word is up against that of a teenage girl, which means in the court of public opinion, they always win, with Christina powerless to stop them.

There are some supernatural red herrings and Cooney herself presents Christina as a potentially unreliable narrator on multiple occasions (particularly in The Fire, when Christina seems to always have matches spilling from her pockets that she doesn’t remember putting there, further cementing perceptions of her as a potential arsonist), but the reality is that everything Christina says about the Shevvingtons is true. Her perception of them is not flawed—they really are horrible people. Anya isn’t suffering from nervous exhaustion—she has been intentionally driven to her breaking point by the Shevvingtons. The creepy giggling Christina hears from the cellar of the Schooner Inne isn’t a figment of her imagination—the sound is coming from the Shevvingtons’ son, whose existence they have kept secret and who is lurking around in the Inne, the cellar, and the surrounding tunnels.

The ocean, the tides, its beauty, and its potential violence are a constant theme that runs throughout Cooney’s trilogy, giving the series a concrete, specific sense of place, in contrast to many of the other ‘90s teen horror novels that could take place almost anywhere, either because of the urban legend familiarity of their storylines or the banal representation of the average teen’s daily life. In the opening pages of The Fog, Cooney lovingly describes Burning Fog Isle through Christina’s eyes, in her anticipation of nostalgia and longing as she prepares to head to the mainland. Christina is, in many ways, a personification of the island itself, and “she had had a thousand photographs taken of her, and been painted twice. ‘You are beautiful,’ the tourists and the artists would tell her, but they would ruin it by smiling slightly, as if it were a weird beauty or they were lying” (The Fog 5-6). While Christina loves the island, she compares herself unfavorably to mainstream ideas of beauty, thinking that “she had never read anything in Seventeen about strength as beauty” (The Fog 6), though this strength is what will ultimately save her. Both the island and the mainland are quaint, with year-round residences existing alongside vacation homes, seasonal souvenir shops, and ice cream parlors, in a landscape of dual, intersecting spheres that is further complicated by the tension between people from the island and the mainland. The world Cooney creates and the dangers Christina encounters are specific to this particular place, though this belies the tradition of violence that Christina uncovers and marginalizes a horror that women everywhere encounter, creating a narrative of containment and silence even as Christina herself refuses to capitulate to either of these.

Christina tells the truth about the Shevvingtons to anyone who will listen—and several people who would really rather not and are quick to silence and dismiss her—and works to uncover evidence of the Shevvingtons’ abuse of other teenage girls in the places they lived before they moved to Maine. At every turn, she is ignored, betrayed, and has her sanity and motivations questioned. As Christina looks back over the struggle in which she has been locked with the Shevvingtons for the entirety of the school year, she comes to the realization that “That was the whole key—make it be the girl’s fault. Make her be weak, or stupid, or nervous, or uncooperative…. People could not accept the presence of Evil. They had to laugh, or shrug. Walk away, or look elsewhere” (The Fire 145).

Cooney presents a personal and cultural narrative of trauma and abuse that feels familiar to even today’s post-#MeToo reader. Christina, Anya, Val, and others are controlled, gaslighted, and torn down, as the Shevvingtons work to dismantle their sense of self-worth and identity, separating them from those who would support them and systematically destroying them. While Cooney does not explicitly recount sexual abuse, the Shevvingtons are frequently described as touching the girls upon whom they prey, even having the girls sit on their laps. The girls’ physical, emotional, and psychological boundaries are all under attack and transgressed. Christina begins to suffer from dissociation and blank spots in her memory, particularly in the trilogy’s final novel, The Fire. She distinctly recalls the sense of separating herself from her body as she lies in bed, torn between the freedom of not having to acknowledge or cope with what is happening to that body and feeling an overwhelming sense of responsibility to return to it and continue to fight, to reclaim her own identity and agency, and to help the others girls the Shevvingtons have abused. These elisions go largely unremarked—other than problematically being used to cast doubt on Christina herself and the reliability of her perspective—and allow Cooney to avoid having to directly address the unspeakable possibilities that lurk within those silences.

Christina’s parents, peers, and the townspeople finally recognize the Shevvingtons’ crimes, the experiences of their victims are validated, and several people even apologize to Christina for not believing her. Christina’s is a story of perseverance and resilience, as she clings to her own understanding of reality and defends the Shevvingtons’ other victims when they cannot defend themselves. As she tells herself repeatedly over the course of the trilogy, she is “island granite,” unbreakable. But as the name of the series unsettlingly suggests, Christina has been “lost” and she had to find herself. No one else came looking for her and there are likely parts of herself that will remain irretrievable, like her innocence and her enthusiasm for mainland life that has been compromised and corrupted. Christina has suffered and has earned the belief and support of those around her… but following the perfunctory apologies and reconciliation, the default is to retreat once more into silence, to not speak of the Shevvingtons, to not tell other children about the terrible things that have happened. Christina is resistant, thinking “that was silly. The more knowledge you had of evil, the better you could combat it. How could anybody learn from what she had been through if nobody would admit it had happened? Out there somewhere, in another state, in another village, another thirteen-year-old girl might come face to face with evil for the first time. She had to know what to do, how to tell the world” (The Fire 195).

The resolution of Cooney’s Losing Christina series is complex and problematic, both for Christina and for Cooney’s young readers. The message is simultaneously empowering and silencing: Trust your intuition, but know that no one else will believe you. Speak the truth, even though no one will listen. You are strong, but when going head-to-head with adults or other authority figures, your strength is meaningless and you will have no viable means of resistance beyond remembering and enduring. Even when the truth is undeniable and the victory ostensibly won, it will be acknowledged only to be erased, ignored, and silenced. It is all too easy—and all too heartbreaking—to imagine the young readers who could relate to these novels reading between the lines to see their own story being told (however incompletely) and their own strength reflected back at them through this formidable heroine, only to find themselves relegated once more to marginalization and silence.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.