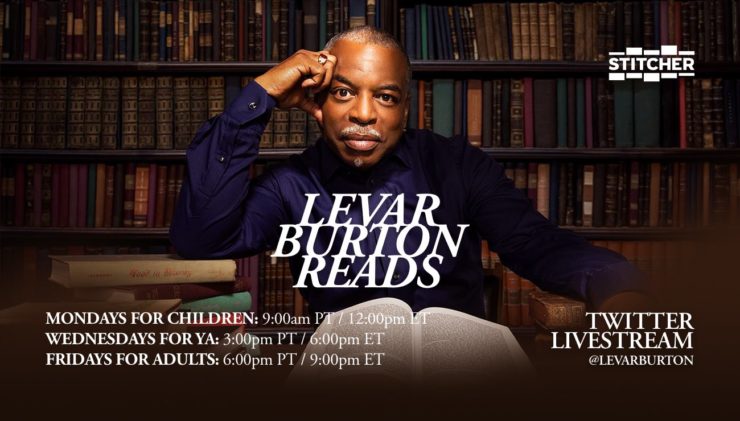

The first place winner of the LeVar Burton Reads writing contest, as co-presented by FIYAH Literary Magazine and Tor.com!

A runaway and indentured thief, Eri must provide a new secret to open each new lock, at the cost of her own memory. Hundreds of locks later, Eri can barely recall her own past. An unanticipated alliance with a musician may prove the key to both their freedoms—if Eri doesn’t lose herself in the process.

Eri arranges her truths like the tiers of a wedding cake. The most complex memories are the bottom layer, used only in the direst situations, and the smallest and most delicate rest on the top, waiting for small and uncomplicated locks, the kind anyone can open. There aren’t enough of those, in Eri’s opinion.

She takes shallow breaths in the still air of the hold as she shuffles from one chest to another, throwing up dust every time she moves.

The lock on the next chest glows red when she approaches it. It’s a standard truth-lock, spelled by Mr. Gilsen’s lockmaster to recognize its true owner. He’s a wealthy passenger unlucky enough to have hired Mareck’s whole ship for his travel, and he’ll be the last person Eri has to steal from.

“Open,” she says.

“I require a truth.”

“I am your rightful owner.” It never works on the locks she deals with, since it’s a lie, but she’s supposed to try, to test for weaknesses. This lock remains a stubborn red.

“I require a truth,” it repeats.

Eri reaches for her tiered truths and plucks out the one that seems least painful to lose. “The ship that brought me from Ekitri to Sild was overcrowded, and my bunkmate elbowed me in her sleep and bruised my jaw one night. It hurt to speak for weeks. I learned to make myself understood without speaking; this is why Mareck picked me to be a lockbreaker.”

The lock glows a soft, welcoming yellow. The ache in Eri’s chest deepens a bit. She wonders what she just gave up.

It’s a tricky business, opening truth-locks. Only truths a lockbreaker has told nobody else can open a lock. As soon as a truth is spoken aloud to the lock, it disappears, unusable—and the memory that sparked it goes too. Lockbreakers, in addition to possessing an organized mind, must have a quiet disposition. Eri often thinks how much easier this would be if others pitched in, sharing their few easy truths. But the Sildish Empire is fond of its order, and its citizens are as well; none of them would agree to relinquish control of themselves like that. It’s hard for most people. And so Eri is here, alone as always.

The trunks are stacked on top of each other higher than Eri’s head. They’re not the same size or shape, and though the dockhands who loaded the ship must have tried to keep them steady, the trunks at the tops of the stacks wobble with the steady motion of the ship. Everything is brown, even the air, and her lamp barely emits light. Mr. Gilsen, who is traveling across the ocean for his daughter’s wedding, paid for very strong locks; every trunk requires sizable truths, even those that Eri guesses don’t contain anything particularly valuable.

Ten days, Eri tells herself. Ten days. In ten days, they will land on Kagewei Island, and she will report to Mareck for the last time and walk off the ship forever. It will be the last of five journeys, and ten days is not a long time. She has opened nearly two thousand boxes since Mareck bought her from the prison ship and wrote her a contract: open every box on five ships, and he would let her go, far from where she came from, a free woman.

Eri is tired of keeping secrets, of hoarding her past like so many coins, deciding which are worth a lot and which are worth a little. She is tired, yes, and sad. She remembers facts about her life, overarching ideas, but she has given thousands of memories to glowing red locks, and she doesn’t have many details to hold onto anymore. In ten days, she will be free, she repeats to herself, however much of her is left.

She tells the next lock to open, feeds it the bright flicker of hope she felt when Mareck unlocked her chains and escorted her off the prison ship, the way that hope curdled to dread when he outlined his plan for her. She won’t mind not being able to remember that every morning.

“Hello?” someone says, cautious. The voice is unfamiliar.

Eri curses, loudly. No one is supposed to be here. She lifts her lantern and looks in the direction of the voice. A young woman, tall with long brown hair, stares back from a few paces away. She’s dressed all in purple and stands in front of a flat wooden chest. The purple and the fine cut of her dress mark her as a musician. Not a stowaway, then. Just another part of the Sildish government’s intricate web of control.

Eri starts out polite. “Can I help you get back to your cabin?”

“No, thank you.” The woman flushes from her neck to her forehead, but she stares Eri down nonetheless. “I was just looking for something.”

“Nothing down here to benefit a musician.” Eri hooks a thumb in her belt loop and tries to look friendly. “Let me escort you out.”

“Actually,” the musician says, “I’m wondering if you could help me with something. You’re a lockbreaker, right?”

Eri shakes her head. “I’m just looking for damage down here.”

The musician crosses her arms. She is much taller than Eri, but then, most people are. “Then why did I see you unlocking that box?”

Shit. Eri’s heart drops into her stomach. Mareck said no messes. But what’s the cleanest way to get the musician out of her hair?

Eri drags a trembling hand across her forehead and tries for a pleasant, comfortable smile. “What do you need, exactly?”

“I just want to borrow something. I need you to open the box.”

“Make it quick, then,” Eri says. “Musicians are supposed to stay in their cabins.” Though Eri has no sympathy for the Sildish Empire’s need to control everyone and everything it touches, she has a healthy fear of musicians. Some rules should be followed. Music, in correct dosages, expands the enjoyment of those who can afford it, but it has to be carefully managed to prevent disaster. The woman leads her to a flat box in another row. “This one.”

“Plug your ears,” Eri warns. “If you hear this, it won’t work.” The musician sticks her fingers in her ears dutifully. Eri opens the lock with something small: the only memory she has of music, played at a wedding she attended as a child. The music itself is impossible to keep in her mind, but she describes the swirling color of the dance floor, the giddiness of being so young and, briefly, so happy. Eri gestures to the musician that she’s done.

The musician takes the lantern from Eri’s hand and holds it up, rummaging through sheaves of paper. The lantern lights half her face like gold fire. Her brown hair, otherwise dim, gleams. She pulls a few sheets of paper out. Eri catches a glimpse of delicate slanted symbols, but they mean nothing to her.

Eri takes her lantern back, accidentally catching the calloused fingers of the musician. “Neither of us were here,” she says.

The musician nods. “You can replace these tomorrow if you meet me at the entrance to the passenger quarters at seven.”

Eri is three minutes late to meet with Mareck, and he taps his watch meaningfully when she arrives at his cramped office.

“Sorry,” she says. “I was working on a tricky one and didn’t want to quit.” He smirks. “Look at our little lockbreaker, learning to like her work.”

“Here.” Eri hands him her list of the chests she’s unlocked. Someone will come in to empty them of their most valuable items, replace the goods with rocks and straw, and relock them while she rests.

He flips through the pages. “Anything interesting I should know?”

“There was a—” Eri knows she should report the musician to him. If she doesn’t and he finds out…well, she’s seen what he does to his sailors. But a thought occurs to her: maybe the musician will play for her. She’s heard of what music does—drives people wild with delight, makes them dance until their shoes fall apart, careless of their bleeding feet—but she thinks it must be possible to use it for something gentler.

Mareck is staring at her.

“There was a damaged chest,” she says instead of finishing her thought. “Can’t tell if it was our fault or his, but it may be worth making sure he doesn’t throw a fuss.” She makes a mental note to put a dent in something tomorrow.

“Right,” Mareck says. There are streaks of gray in his hair. He looks bored. “They’re not supposed to complain until we’re long gone,” he says.

Eri can read the tension under his words. There’s a time limit on this. On their past journeys, their ship mostly carried cargo that would then travel over land for weeks or months before being unpacked. This gave them time before their theft was discovered and left the owners with a multitude of suspects to blame. This is the first passenger journey they’ve undertaken—the reward is greater, but so is the risk.

But the sustainability of Mareck’s operation isn’t Eri’s problem. After they get to Kagewei, she doesn’t care what happens to him or his ship.

He waves a lazy hand at her. “Go on,” he says. “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

At dinner, Eri finds herself shoved into the same group of people she always is. They tolerate her silence, and that’s fine. She doesn’t have anything interesting to say. Stories are currency among the ship’s workers, and she has none to spare.

She dips her hard biscuit into her pea soup and avoids her bench mate’s elbow as he gestures in the middle of a tale about a woman he met at the ship’s last stop. Eri hasn’t been allowed on land since she entered the prison ship.

Ten days, she whispers to herself. She stares at her soup and hopes the biscuit will soften quickly.

The woman across from her, Caris, has been serving the musicians in their rooms, and she’s telling the group her discoveries. The start of a new voyage is always good for gossip. The wedding Gilsen is throwing his daughter will be the biggest ever held on Kagewei, and easily the most expensive. Twenty-five musicians are being brought in, a full chamber orchestra. It’s the largest number the government has ever let out of Sild at once. They are guarded, of course, though Caris says they seem to bear the passengers and crew no ill will.

“Are they practicing on board?” the man next to Eri asks.

Caris nods. “They’ve given me plugs for my ears. They’re making sure not to endanger any of the other passengers. A touch of music and you’re dancing over the rail, I imagine.”

Eri thinks she heard music once, as a child, but she doesn’t have the memory of it, only aware that it happened through memories of conversations about her aunt’s wedding. She liked it, though. She’s sure of that.

The musician holds a finger to her mouth when they meet.

“The guards switch in five minutes,” she whispers. “They’ll be distracted then.”

There are two entrances to the wing where the musicians are held, Eri finds out, and as the guards chat with those replacing them, they bunch around one entrance, leaving the other free for Eri and the musician to tiptoe through.

The musician has a tiny room to herself—a luxury. The bed is bolted to the floor like

any other, a plain thing with a flat cloth mattress, but there is a chair bolted down next to it as well—a padded, self-satisfied piece of furniture that doesn’t belong. The walls are covered in a thick black substance, though the wood of the ship beneath it is visible at the corners.

The musician follows her gaze. “It’s soundproofed. We practice all the time.” “I didn’t tell my supervisor you were stealing music,” Eri says.

“And I didn’t tell my handlers anything at all.” The musician extends a hand. “Anea.” “Eri.”

Anea’s fingers are calloused, but her palm is soft.

“You could have opened the box yourself, you know,” Eri says. “They tell you it’s impossible, but it’s not. You just have to think of something you’ve never mentioned to anybody.”

Anea draws her hands away. “I know. I used to open locks, when I had to. But using any memories of a time after I started learning music might lose me the practice time and the skill.”

“Why open locks, then? Why steal music?”

“It’s music they’re going to give us later. It’s a test, to see how quickly we can polish our performance. I need extra time to prepare.”

She sits on her bed, moving her wide skirts. Eri sits on the chair that must, she realizes, be meant for practicing.

“Why do you need extra time?”

The musician spreads her arms helplessly. “I’m not good enough. They test us all the time, and I only pass if I cheat. I’d be doomed if I couldn’t practice ahead of time.”

“Would they throw you out if you failed?”

Anea nods. “And they’d keep my violin. I don’t know how long I’d last without it.” She shivers. “Not long. It’s like locks. There’s a give and take, and the violin mostly takes. Without it, I don’t know if I’d be myself.”

Eri considers what she’s heard of lockmakers, the way they end their lives surrounded in rooms of locks, unwilling or unable to leave, rotting away like the rusty metal around them. “Oh,” she says.

“So, uh, do you mind if I practice a little with you here?” Anea asks. “I’m not quite done memorizing.” She looks a little uncertain. “I can do it silently if you prefer.”

“Oh, no,” says Eri. “I’d love to hear you play. Free music is a rarity.”

“It shouldn’t be dangerous, since it’s just my voice and not my violin,” Anea says, but a slow flush rolls up her neck. “Still, it might be a bit strange.”

“I understand,” Eri says.

Anea unrolls the first few sheets of music, clears her throat, and begins to sing. Her voice is thin and clear, true to the notes but without flourish. Eri slides off the chair and onto the floor and looks up—at the ceiling, at the musician—and listens.

When Anea sings, her fingers dance along the air with her notes, and she tilts her head just so. Though Eri has her sea legs, she feels the sway of the ship through her shoulder blades and hips while she lies on Anea’s floor. It reminds her of the first days on the prison ship, when she yearned for solid land and the steady grip of her knife more than freedom. She tells herself she will be back on land soon enough.

The melody that Anea sings is festive, upbeat, but it makes Eri more melancholy than ever. The memories don’t hurt anymore, not really. It’s their absence that hurts. When she tries to remember what she ate in prison. When she tries to tell herself a story from her youth and finds halfway through that she cannot recollect the names of the childhood heroes who captured her imagination. There will be something left after she finishes the remaining boxes, but not

much. How will she start a life if she has nothing to base it on?

She closes her eyes, and for the briefest fraction of a second, she is back in Ekitri, a small child at her aunt’s wedding. Someone is playing music, and the adults are smiling, removing uncomfortable shoes, taking each other by the arm, dancing, dancing, dancing until they are wild with glee. She takes a handful of her dress, red cloth dotted with small white and pink flowers, and decides she’s not too tired, she can dance too.

Eri opens her eyes and sits up. Anea stops singing.

“What’s wrong?”

“A memory!” Eri gasps. She reaches for it again. The music and the dancing fade away like a dream after waking, but the feel of the soft cotton in her sweaty grip and the sight of the tiny white and pink flowers remain. “Your song gave me part of a memory back.” The place in her chest that aches, aches, aches when she talks to the locks glows warm for an instant. She didn’t know that was possible.

Anea frowns at her. “You must want your memories back very much.”

Eri doesn’t have friends, isn’t sure she knows how to have them. The last time she trusted someone it landed her in prison. “I’ve been lockbreaking for months.” She lies back down on the floor and tries to find its comforting movement again, but it’s gone.

“How much have you lost?” the musician asks quietly.

“Too much.”

“What can you tell me about yourself?” Anea’s voice is gentle—almost too gentle. Eri aches hearing it.

When she started on this ship four months ago, with indifferent cargo in the hold and the kind of hope that comes from getting out of prison, she tried lying to make friends or meet lovers in the mess hall. I’m a lost princess from Kantarang. My father made shoes out of the finest goat leather; we don’t have cows where I’m from. I’m the bastard daughter of a diplomat who fell in love with a servant—yes, that’s why my skin is this color.

Eri has to portion out her big truths, so she goes with precious detail. “Where I grew up in Ekitri,” she says, “there are only hills and no mountains, and the hills bloom once a year in a thousand different colors, a special variety of flower for every possible hue.”

“What did you do with the flowers?” Anea asks, and Eri cannot remember. She curses herself for being foolish when she started this job, for not knowing what to preserve, or how.

“I don’t know,” she says, staring up at the ceiling, beginning to feel the hardness of the floor. “I’ll have to go back someday. I don’t know.”

“If I had my instrument,” Anea says, “maybe I could help you remember everything.”

“Oh,” Eri breathes. She’s always heard that music’s magic is in the instruments, which must explain what Anea said earlier. “But won’t it be dangerous? Won’t it make me wild?”

“Music knows who you are,” Anea says. “It gives you what you want.” She shrugs. “Most people want to dance, to forget themselves for a moment. It’s when they want something darker that bad things happen. But you don’t want to dance or have fun or die. You want to remember. You want to be someone who remembers.”

Eri rolls onto her stomach and looks up at the musician. “Is that why you still play? Because you can see what people really want?”

Anea’s mouth twists. “It’s like I said earlier. If I’m separated from my violin, I’ll be… ungrounded, like a tree ripped from its roots.” She looks Eri in the eye. “I’ll be as good as dead.”

When she finds Anea wandering the hold again two days later, looking a little like a lady

ghost searching for a lost lover, Eri wonders if they have the seeds of the same idea winding through their heads. She can’t get the thought of Anea being separated from her violin out of her mind. And she’s losing too much every day. She’s not sure there will be much of a person left by the time Mareck lets her off the ship.

“There’s nobody here but us,” Eri says in greeting. “And the boxes.”

Anea whispers anyway. “I was just thinking. I could really help you, you know, with the memories, if I ever had a moment free with my violin, but they keep such a close watch on me.” She closes her eyes. “And even with knowing the music ahead of time, I’m falling behind. They’re going to test us again after the wedding, and this time, I really think I’ll fail.” She seems to sway with the ship, and Eri can hear her breathing, shallow and panicked.

She puts a hand on the musician’s arm. “I have an idea,” she says.

“I’m listening.”

“Let’s steal your violin and run away once we reach Kagewei. My contract ends there, so I’ll be free to go, and I can get your violin while you sneak away too. I’ll be empty of everything by then. But with the violin, you can play my memories back. We can both be people away from here.”

“If we get caught, we’re as good as dead.”

“If we don’t try, we won’t have anything left to make life worth it. The locks have everything of me,” Eri says. “Your violin has everything of you.”

“We won’t have any money.”

“I’m already opening boxes filled with valuables. I’ll steal something small, enough to get us passage somewhere far away from here.”

A smile unfurls across Anea’s face, a bit wobbly. She’s trying to be brave, but she’s nervous. Eri is too. It’s a terrifying idea.

“Okay,” Anea says. “Okay. Let’s try.”

If everything goes to plan, Eri will step on land for the first time in years. Anea will give Eri her memories back. From Kagewei they can go anywhere at all.

The day before they’re due at Kagewei, Eri’s hopes shatter against a small black box with the biggest and most complicated lock she’s ever seen.

“Open,” she tells it softly.

“I require a truth.”

Eri jumps. The voice is harsh and multitoned, the loudest she’s ever heard. She turns and finds the ladder, climbs out of the hold, and marches right to Mareck’s office. He raises an eyebrow when she arrives, panting slightly and red with rage, at his door. “I’m not supposed to see you for another six hours,” he says.

Eri’s rage-fueled courage doesn’t hold up. “Sorry,” she says. “It’s just—” She pauses, hoping he’ll cut her off, anticipate her complaint, but he doesn’t. “There’s a box I can’t open.”

His expression doesn’t change. “The small one? Have you tried it?”

“I didn’t have to. Opening that thing will destroy me, Mareck.”

Mareck fingers the papers in front of him deliberately. “That box,” he says, “contains the bulk of Gilsen’s wealth on this ship. It has jewelry, papers, money. You’re not a stupid girl, Eri—you know as well as I do that he’ll be looking for me once the thefts are discovered. I need that money to get out of here. To go somewhere else and start fresh.”

“That’s awful,” Eri says reflexively.

He nods. “Maybe so. But you signed a contract when I rescued you from that prison ship—every box will be opened.”

Something in Eri’s chest curdles. He’s never meant for her to have hope.

Eri goes back to the hold. She unlocks all the remaining boxes except the small one. Then she stares at the large lock and takes stock of what she has left. Her time in prison has shriveled to nothing in her brain. The details of everything before that have been plucked away: the man she was meant to marry, the ship she left Ekitri on, the handsome thief who betrayed her and sent her to prison, her family and their compound in the hills, herself the quietest and youngest of the bunch. They are concepts, the skeleton of a personal history, but she has no memories with which to flesh them out. She’s a shell, an instrument nearly past its usefulness. They arrive at Kagewei tomorrow.

Eri goes back to the kitchen and finds Caris, carrying trays of food, just exiting. “Can I take these in for you?” Eri asks.

Caris shrugs and hands over the trays. “Less work for me.” She reaches for the plugs in her ears and gives them to Eri too. “Just in case.”

The guards let her past without so much as a blink.

Anea takes the food from her absently before she recognizes Eri. She smiles first, a bright, instant thing, but her expression quickly turns to confusion.

“What are you doing here?”

Eri puts a finger to her lips and closes the door behind her. “There’s a problem.” Eri tells her about the black box with the giant lock in the hold, about how she won’t be allowed off if it’s not opened. “I can’t open it and the chest with the instruments,” she says wearily. “I just can’t.”

Anea, sitting completely straight on her bed, stares at her with blazing eyes. But her voice is soft, as clear and gentle as it was in song. “We agreed, Eri,” she says. “We have to try.”

“This box will erase me, Anea. Once I open it, I won’t be a person anymore.”

Anea leans forward, grips Eri’s hands. “You will be,” she says. “I will play you back to life.”

Eri knows, looking at her, that Anea is her only hope of reclaiming her past. That giving up everything is her only hope of getting anything back.

“Okay,” she says. “Okay.”

Eri wakes early the next morning. That is, she hasn’t slept at all.

She sneaks down to the hold well before breakfast. That’s the plan. The crew will start unloading as soon as it’s light out, but the passengers, Gilsen and his group of musicians among them, won’t leave until after breakfast.

Eri has to get everything done before then. Before she goes, she rips out a page of a cabinmate’s book and writes down a list of the three things she needs to do. She hopes she won’t need it.

When she faces the black box, Eri can feel her heartbeat in her throat and palms. “Open,” she commands.

“I require a truth.”

Eri sits in the space between boxes and talks. She tells the lock about the house she grew up in, the way vines grew up the walls and over the windows, the taste of the rolled corn and mangoes they ate for breakfast. When she pauses to take a breath, she looks at the color of the lock. It is as red as ever, so she takes a breath and keeps going. She has only large things to say now. Her chest aches and aches and aches. Her mind races, searching for details she’s lost, knowing they were just there. Her heart begs her lips to stop moving.

“When I was seventeen,” she says carefully, “I was arranged to be married. I wasn’t fond

of the idea. My sister helped me get the money to buy passage on a ship and run away.” She goes on, telling the lock of how she was befriended and betrayed by a thief who tricked her into thinking he was her choice, who made her believe that what she did for him she did for good, and who vanished when she got caught. Here, she pauses. The lock is orange. Of her time in prison there is little left to tell, but tell it she does, and then she describes her first steps on this ship, the Itation, the stories she heard in the mess hall, her check-ins with Mareck, how she hates his lined face and low chuckle. She continues right up to the moment before she met Anea, and the lock glows a warm, yellowish orange. So close. Her brain is screaming at her, begging her to stop, to save what little she has left. But she remembers Anea, that the music can bring her memory back.

Eri’s mind is a gaping blank, a vast white emptiness punctuated by the occasional contextless image.

She tells the lock about meeting Anea and their plan. She closes her eyes as she says it. “And we will walk out, and the sun will be shining, and I will stumble when we hit dry land. But we will be free.”

She opens her eyes. The lock is butter yellow. It clicks open when she puts her hand to it.

Eri has something she’s supposed to do. It’s for someone else, someone she’s made a deal with. Does she trust this person? She doesn’t know. She doesn’t know anything. She doesn’t know what matters.

She turns to look for a way out, and a piece of paper stuffed in her shirt pocket brushes against her arm.

- Unlock the musicians’ chest, it says, in her own handwriting.

Where is the chest? The musicians live above, by the passengers. Eri knows that much. She goes down the corridor, up the ladder. In the hallway, people in purple are assembling, packing things up, murmuring about food. One of them is tall and has brown hair, and she looks at Eri with worry when she passes.

Eri opens what must be the wrong door. The tall musician pushes her gently at another, and her fingers linger on Eri’s shoulder.

“This one,” she says urgently. “Hurry. We’re leaving soon. I’ll distract them so they don’t notice you.” Eri nods and watches her leave. Perhaps they knew each other once. There is a large metal chest in this room. It must be the one she’s meant to unlock. “Open,” she says.

“I require a truth.”

Eri stands in front of it and closes her eyes. There is no structure left to her memories; there are simply images floating through. She describes them. A grassy hill in the fall, hunger and impatience. A long, dark, low-riding ship that clinks as it moves. A red dress with white and pink flowers bunched in her hand, lace at the hem. The long, pale neck of a violinist moving her fingers with no instrument to hold, a clear melody sung aloud. The rocking of a ship beneath her shoulders. With every word, the emptiness in her chest, in her mind, grows. The lock turns toward orange but remains decidedly red.

“The truth is,” she says helplessly, “I have no truths left to give.”

The lock clicks open.

She stumbles forward and looks inside. There are cases and cases of instruments, and she doesn’t recognize any of them. She looks at the crinkled paper in her hand. 2. Steal the light-colored violin. The handwriting looks like her own.

She thinks she knows what a violin is. The room is small, but it feels large. The echoing emptiness in her head seems to spread to everything around her.

She has something to do. She opens the instrument cases, looking for light-colored wood. One small instrument is a pale tan color, and it gleams even in the dim light. The lockbreaker closes the case, which she grabs. She has the instrument. She turns back to the paper, her only tether, messages from her past self.

- Get back to Anea’s cabin. Anea, that must be a name.

But who is that?

The lockbreaker stands in the room, surrounded by instruments. The walls seem to recede. Everything is emptiness. Perhaps she will just sit here.

She folds her legs and sits on the floor. The floor rolls pleasantly beneath her, and beneath the dust, some of the wood smells like pine.

She has a task. She must think who Anea is. She remembers a pale hand, dark hair lit by a lantern, a smile rolling across a face.

The lockbreaker opens the case and runs a gentle hand over the violin. It is smooth, well cared for. She can just sit here with it for a moment.

The door to the cabin opens. A tall woman in purple looks down at her, light from the lantern in her hand illuminating her pale face and brown hair. Her mouth creases into worry when she sees Eri, and though Eri does not recognize her, she wishes to smooth her face back out into something lovely.

The woman bends down to take the violin from Eri’s hands and presses a soft kiss to Eri’s temple as she straightens up.

“We don’t have much time,” she says, opening the case, making sure the soundproofed

door is sealed, “but what we have, I will give you.”

She puts the violin to her chin and begins to play.

“The Last Truth” copyright © 2022 by AnaMaria Curtis

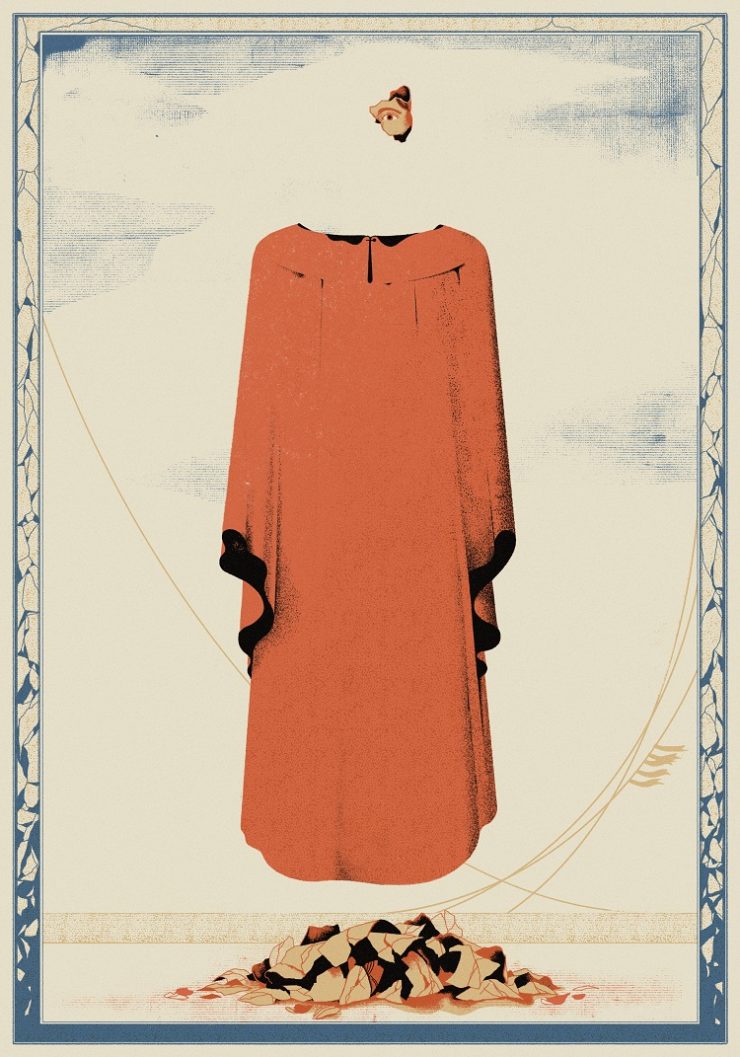

Art copyright © 2022 by Juan Bernabeu