There’s a moment I find especially haunting in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s not the death of HAL (although who wasn’t moved while watching the soft-voiced computer betray a humanity that Dave Bowman, the astronaut disconnecting him, barely got close to exhibiting). No, what I’m thinking of comes before. WAY before.

It comes, in fact, in the “Dawn of Man” sequence, even before the SF stuff officially kicks in. It comes as the man-ape tribe—if you can even call it a tribe—cower at night, under a protective outcropping of rock. At this point, their rolls of the evolutionary dice have repeatedly come up snake eyes: They survive on whatever eats their barren environs provide; one of their members succumbs to a leopard attack; and they’ve been driven away from their water hole by more aggressive rivals. Now, in the dark, they huddle together, listening to the muffled roars of nocturnal predators, barely daring to issue their own, ineffectual challenges. And this is the moment that catches me: Kubrick cutting to a close-up of Moonwatcher (Daniel Richter), the de facto leader of these proto-humans, as he stares into the dark, the brilliant costume design of Stuart Freeborn allowing us to take full measure of the man-ape’s nascent humanity as he gazes out into the unknown.

I think about that moment. For Moonwatcher, it must exist in a continuum—this can’t be the only night when these creatures have been all-too-conscious of the threats without. I think about how instinct and a developing intelligence have led them to their best defense against unknown terrors: the security of a sheltering rock, and the comfort of each others’ presence.

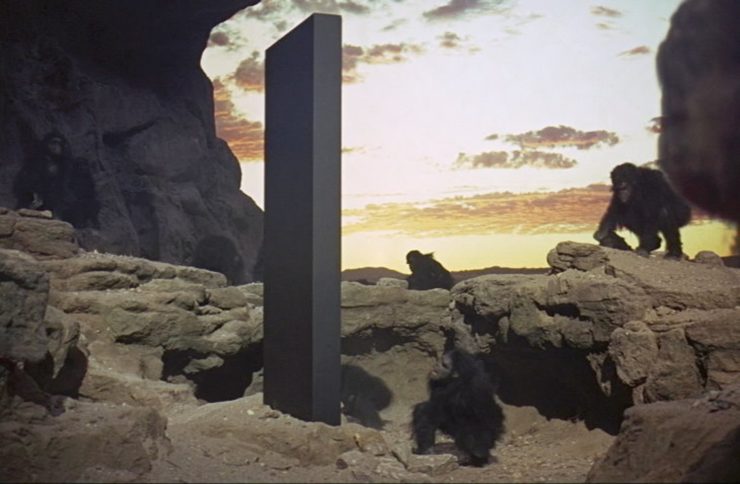

And, in the next scene, the man-apes’ confidence in this meager brand of security is shattered. Legend has it that Moonwatcher and his tribe were, upon the dawn, originally supposed to behold a pyramid plunked down before them. Kubrick nixed that, opting instead for the black monolith. There couldn’t have been a more genius decision. The juxtaposition of this precise, elemental form against the chaos of the natural world—heralded by Ligeti’s breathtaking Requiem—serves as a perfect metaphor for these creatures being brusquely confronted with the realization that the world, the universe, is greater than what looms outside of their humble…hell…wholly inadequate shelter. The cosmos has come a-knockin’, and everything these almost-humans thought they knew has turned out to be wrong.

It’s human nature to seek security, predictability. We are pattern-forming creatures, anything that breaks the comfort of routine can alter us in profound, sometimes life-changing ways. Nature does it on the more malevolent side with hurricanes, earthquakes, and insanely contagious and deadly viruses; and on the more benign side with stuff whose random improbability shakes us from our cozy preconceptions: the Grand Canyon; and whales; and a moon to remind us there’s a whole expanse of possibilities beyond the place to which gravity holds us.

But humans can also have a hand in changing the way we see things. There’s art, storytelling, and— specific to our purposes—the movies. Not all movies, mind you; sometimes you just wanna see Vin Diesel make a car go really fast. But for a filmmaker who’s so motivated, the visceral experience of watching a film can propel viewers into a better understanding of themselves, and everything around them.

Any type of movie can do this. Yojimbo casts a sardonic eye on the unintended consequences of getting vicarious pleasure from watching the bad guys pay for their sins. Nashville surveys a frequently derided music genre and finds within it pockets of nobility. Judas and the Black Messiah examines the daunting moral triangulations behind the fight for equality.

But of all the genres, science fiction seems the most suited to the task. Straight drama, or comedy, or even musicals remain rooted in our earthly, observable realities; what can be glimpsed outside your window can also be up on the screen. SF—by dint of reaching beyond, by speculating on the possible, by asking, What if…?—can break through the simple equation of “what is seen is what is,” can prompt us to imagine alternatives, and can get us to question whether what we know about ourselves is as absolute as we believe.

That’s the thing that keeps drawing me back to SF, the opportunity to—forgive the archaic term—have my mind blown, my preconceptions shattered, my—forgive the Bill Hicks-ism—third eye squeegeed clean. What I want to do in this ongoing series of articles is take a look at the films with that power, divine what messages they might be trying to convey, and consider the lessons we as humans can take away from them.

Buy the Book

Until the Last of Me

And let’s start with that poster child of mindblowers—the “Ultimate Trip,” as the MGM marketing department once proclaimed—2001: A Space Odyssey. For a sec, though, let’s just ignore the whole final act—the psychedelic stargate voyage and the telescoped lifetime-in-a-Presidential-Suite bit—and examine something a little bit more subtle, something that director Stanley Kubrick, with an assist from Arthur C. Clarke, was threading throughout the course of the film.

Kubrick is on record as saying that the only overtly funny thing in the film is the shot where Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), en route to the moon, struggles to decipher the arcane instructions of a zero-gravity toilet. But that doesn’t mean Kubrick’s tongue wasn’t firmly planted in his cheek in a number of other moments. Given the director’s keen eye toward our frailties, there’s no way he could tell this tale of humanity’s initial adventures beyond our earthly realm without casting an acerbic eye on how we might cope with crossing the threshold into the vastness of space.

In the Dr. Floyd sequences, it takes the form of the creature comforts we might bring with us. There are simulated chicken sandwiches, and sterile, corporate conference rooms, and brand names everywhere. (One of the grand, unintentional ironies of 2001 is that, by the titular year, most of those brands no longer existed.) Little things to tether us to our earthbound lives, to shield our minds from the implications of what we are confronting, the same way a spaceship’s metal bulkheads would protect our bodies from the icy vacuum of the infinite.

But then, at the end of the act, is the encounter with TMA-1—the Tycho Magnetic Anomaly 1—a single, simple, black monolith standing at the bottom of a human-made pit. An enigma for which comforting, logical—by human standards—explanations are nowhere to be found. Could it be a natural formation? Nope, it was “deliberately buried.” Maybe it’s a part of a larger structure? (Temples on the moon? Hitler’s secret Nazi space base?) Nuh-uh. Excavation reveals just the single, elemental artifact. There is, quite literally, no earthly explanation for it, and no amount of Howard Johnson’s Tendersweet clam rolls will mollify the sledgehammer realization that humanity has encountered something beyond its ken. When the monolith emits a single, high-energy radio burst in the direction of Jupiter, it’s as much a wake-up call to comfortable, cosseted humanity as it is to whatever lifeforms are awaiting the alert.

There’s a reset as we move into the next act, aboard the spaceship Discovery and its secret mission to Jupiter. So secret, in fact, that astronauts Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) have not been clued in. Thus, their mandate is tightly focused and mundane: Monitor ship systems—with the help of their omnipresent computer HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain)—and get their cargo, a trio of cryogenically slumbering scientists, to the planet. Routine is not only the order of the day (whatever you’d care to define as ‘days’ when you’re no longer bound to a rotating sphere), but also a comfort. The time is filled with performing calisthenics, eating meals, getting your ass beat at computer chess, et cetera. Even when HAL detects that a critical piece of radio hardware is on the verge of failure, it doesn’t stir much reaction. The astronauts are secure in their training, and there are SOP’s for dealing with such emergencies.

From its release, the standard rap against 2001 is that it’s boring, with the Discovery sequence being held up as culprit number one. The stock response to that is that Kubrick is taking a radical approach to getting us to appreciate the scale at which this story is being told, using time as a surrogate for the vast distances and cosmic perspective that these characters will confront. That’s a valid argument, but I think Kubrick had another goal here as well. In hammering home the stultifying routine, in imbuing his astronauts with the blandest personalities as possible—Poole receives birthday greetings from his parents with the same cool demeanor he greets the possibility that their all-knowing computer might have blown a few circuits—the director is getting us into a zone where a small but uncanny disruption of the order can land like an uppercut.

Depending on which cut of the film you watch, that moment comes either after the intermission or after Bowman and Poole determine HAL might have to be disconnected. When Poole goes on his second EVA, it’s only natural for one to think, What, again? It’s the same oxygen hiss, the same measured breathing. While the shots and cutting are not exactly the same, they feel that way. It’s tempting to say to yourself, “We’ve been here before, Stanley. Why the deja vu?” Routine, routine, routine.

…Until, as Poole floats toward the antenna, the pod spins of its own volition. And even before it begins accelerating toward the astronaut, our brain snaps to attention. Something is different. Something is wrong. By the time Kubrick jump cuts toward HAL’s glowing red eye, our sense of normalcy has been shattered.

From that moment on, nothing is routine. Bowman ignores protocol to embark helmetless on his rescue mission; HAL exhibits a cold ruthlessness in executing the hibernating scientists and denying Bowman entrance back into the ship; and Bowman is forced to do the unthinkable: exercise creative thought in order to find a way to save himself—surely the pod’s explosive bolts could not have been intended to facilitate a risky reentry through the vacuum of space.

And then, after Bowman executes the traumatizing lobotomy of HAL and has his perception of the mission upended by Dr. Floyd’s video briefing, we get to Jupiter, and “beyond the infinite.” A lot has been made (understandably) of 2001’s final act, and the advent of the Starchild. Generally, it has been interpreted as an uncommonly optimistic fade-out from the typically cynical Kubrick, the idea that humanity has the capacity to evolve beyond war and violence, to become creatures connected to the greatness of the universe. What’s frequently missed in that read is a caveat: Growth will not come via some mystical, cosmic transformation, but with an act of will. Over the millennia, humanity has exhibited an almost insurmountable capacity to cling to the known, the familiar, the comforting. But, just as Bowman only manages to make it to his transmogrification by breaking out of his routine, so we must make that terrifying move beyond habit if we are to evolve.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick turned his astringent eye towards humanity clutching at its reassuring comforts and calming patterns, and strove to show us what’s possible if only we could see beyond them, if we were willing to abandon our instinctual lunge toward the safety of habit and embrace the infinite potential of a greater universe. The film has been described as trippy, but we should not forget that a trip can only begin when we’re brave enough to take the first step.

* * *

2001: A Space Odyssey has been analyzed, poked, prodded, deconstructed, and reconstructed ever since the moment of its release. I don’t presume mine is the only, or even the most accurate, interpretation. If you have your own thoughts, let’s hear them. Keep it friendly and polite, and please comment below. (And if your main contribution is going to be, “I found it boring,” read on).

I don’t typically consider it my place, when someone says, “I didn’t care for this film,” to respond, “That’s ‘cause you watched it wrong.” In the case of 2001: A Space Odyssey, I’ll make an exception. As noted above, Stanley Kubrick took the radical step of using time to get us to appreciate the magnitude of humanity’s move into space. You can’t watch 2001 like a regular film, you have to experience it, give yourself over to its deliberate pacing. If your sole exposure to the film occurs in a brightly lit living room, with your significant other telecommuting in the periphery and a smartphone delivering Tweet updates by your side, that’s not gonna work for a film formulated to virtually wash over you in a darkened theater.

In the absence of 2001’s rare return to the big screen —the most recent was the Chris Nolan restoration on the film’s 50th anniversary three years ago—the best approach is to find as large a video screen and as kick-ass a sound system as you can wrangle, turn off all the lights, power down all communication devices, and commit. For all the ways that 2001 has been described, there is one thing that’s for sure: It’s a film that demands your complete and undiluted attention. Do that, and you’ll discover why it’s attained its exalted status.

Dan Persons has been knocking about the genre media beat for, oh, a good handful of years, now. He’s presently house critic for the radio show Hour of the Wolf on WBAI 99.5FM in New York, and previously was editor of Cinefantastique and Animefantastique, as well as producer of news updates for The Monster Channel. He is also founder of Anime Philadelphia, a program to encourage theatrical screenings of Japanese animation. And you should taste his One Alarm Chili! Wow!