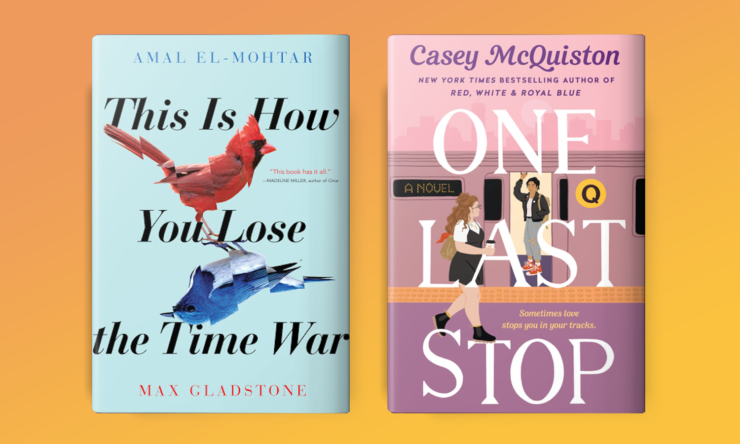

Time loop romances—specifically fantasy romances where characters are caught within a repeating movement through time—are becoming their own kind of genre. Books like Casey McQuiston’s One Last Stop and This is How You Lose the Time War by Amal el-Mohtar and Max Gladstone, as well as screen media like Misfits and Palm Springs, maintain a cycle of chronological struggle throughout the plot. Somewhere out there is an ideal timeline where you and your lover can be together, and the characters are forced to continue the cycle in an attempt to find it.

At their core, time loop romances are characterized by two main ideas. The first is the belief that there must be a better future out there, and the second is that the characters believe they have the power to make it so.

(This article contains spoilers for One Last Stop by Casey McQuiston and This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone. Read the books first. Thank me later.)

One Last Stop, the sophomore speculative queer romance from Casey McQuiston (of Red, White, and Royal Blue notoriety) is about August Landry, a bisexual disaster who runs away from her controlling mother and towards NYU, hoping that maybe she’ll figure out a major before she graduates. She gets a job, three quirky housemates, and an instant Big Lesbian Crush on the very hot butch woman she runs into on the subway. And then August keeps running into her. Over and over again. Same place, any time. Turns out, this woman is Jane Su, and she’s been trapped on the NYC Q train for just about fifty years. And suddenly August has a new problem to obsess over.

There’s a moment in One Last Stop when Jane and August are talking about what might happen after they break Jane out of her time loop (in this case, a very literal time loop, the poor girl is doomed to ride the Q forever) and Jane mentions, offhandedly, that she’ll miss being able to hold a girl’s hand in public. The two characters are still assuming that once they blitz Jane off the subway she’ll return to where she started, in 1977. Queerness might not be as accepted in 1977 as it is in the book’s present-day, but living in the 70s, Jane decides, is still preferable than a never ending ride on the NYC subway.

One Last Stop is unique among time loop romances precisely for it’s explicit, unapologetic, contemporary queerness. Jane deserves better than the Q train, and August is sure that she deserves better than the past that queer people had to fight through. Queer people like Jane and August have a better future ahead of them, and it’s up to them to make it happen.

It’s true that in all time loop romances, the main characters are sure that they deserve a better future than the one they seemed doomed to repeat. In Misfits, Simon goes back in time to save Alicia, masquerading as Superhoodie as he attempts to preserve her life. When Simon dies in the timeline instead, Alicia jumps back in time in order to save him, ending both character’s runs on the show. At some point, both characters break through the time-space continuum for love, determined to have the future they deserve, rather than the dead lovers they keep finding in front of them.

Palm Springs follows a wedding day. From the main characters’ perspective, an eternal wedding day. Stuck in Groundhog Day-esque loop, Nyles and Sarah are doomed to live this 24 hour cycle over and over. They become friends and, eventually, lovers. But after a while, Sarah refuses to be as complacent as Nyles has become, resolving to learn quantum physics in order to get out of the loop. She outlines her plan, gives Nyles a chance to come with her, and they enter the chrono-trigger cave, making out as the world explodes all around them. Sarah has done some tests, but this is still a leap of faith towards a possible better future, together.

Red, one of the agents of time in Time War, is revealed to be the shadowy presence following Blue throughout the character’s ‘past’, in an attempt to protect her lover from her death at the end of the book. The whole story is about their seduction, their romance, their desperate bid to find some future, some timeline, where they can be together.

For all of these characters, including Jane and August, the choices these characters face are either; they remain stuck in an endless, anxious, non-forward loop; or they do something different, they change, adjust, resist. They either move or they remain trapped in a chronological isochronism, a constant repetition.

This repetition anxiety mirrors many people’s daily lives, and this might be why the time loop narrative has surged in popularity, becoming its own sub-genre (looking at you, Russian Doll). When we, as a generation, are continually fighting the same battles day after day after day, the ability to see the outcome of a timeline and then refuse it is a powerful act. How many of us feel like we’re trapped in unending cycles of stagnation after 2020? How many of us feel, every day, that we’re just living for the weekend, or even just Thursday? Alternatively, how many activists feel like we’re just waiting for the next legislative ban to drop? The next hashtag? The next name? With so many people feeling like all they do is repeat their days and their struggles, it’s little wonder why time loop romances, which express a certainty in a character’s ability to change the future, are taking over fantasy narratives.

This narrative inevitably of better-ness is even more poignant for queer romance. As a group of people marginalized specifically because of the way they express love and attraction, queers have a long history of fighting for their rights to exist in relationships with other people, and to exist as themselves in authentic ways. With a queer romance at the center of a time loop, there is an implicit acknowledgement of the give and take of resistance and recognition, the betterness that is out there, the future that could be, if we just fight for it.

One Last Stop acknowledges that Jane Su, a leather-jacket-wearing, short-haired, Chinese lesbian from the 70s was a foremother of the queer lib movement. There is no end to the fight for queer rights, and this book . Women like Stormé, Marsha, and Sylvia, the last of whom passed in the early 2000s, will never get to see the future that could be, that will be, that they helped make.

But Jane will.

At the end of the novel, Jane doesn’t get booted back to the 70s, but instead ends up in 2020 (sans pandemic) with August. She gets all of her time back. She breaks out of the cycle of anxiety, same-ness, and struggle and gets to thrive with her girlfriend, right now. This decision, to give the future back to the people who fought for it, makes One Last Stop a quietly wonderful romance, emblematic of queer resistance throughout the past century.

Because of this theme, the book is existentially concerned with queer history, from the eyes of someone who was a part of the queer liberation movement of the 70s. Within August’s research and Jane’s memories, Casey McQuiston describes a boots-on-the-ground perspective of the queer community that was thriving in NYC fifty years ago. There’s a lot of work done to show not only how difficult it was for queer people to exist in the post-Stonewall, pre-AIDs-epidimic era, but also how that existence was joyful, beautiful, supportive, and aggressively inclusive.

There is, in One Last Stop, an intrinsic hope within the plot. As Jane passes through the world, through time, relatively unchanged, she carries an elder queer resistance with her. In the epigraphs at the beginning of each chapter, we are given a look at the Jane Su that the world remembers; missed connections, fighting bigots on the subway, a booking log after an anti-police riot–all these moments of queer resistance in a world that is not made for her, where she must make room for herself. She is the dyke they did not kill. She is the woman who survived. She is the queer who protested, rioted, and threw down at barfights for her rights, and at the end of the book… she gets to see that change. She survived; she will thrive.

All time loop stories, at some level, deal with death. Time loop narratives are notorious for engaging with the idea that even if you die in the loop, you will come back (Palm Springs, Russian Doll, Groundhog Day). Or if you don’t come back, someone’s coming to get you (Time War, Misfits). Character’s anxiety over death is another way that the loop reflects on the future.

One Last Stop makes the clear choice to avoid death as an option for these characters, but death is important to them. August is haunted by her mother’s search for her missing brother, also named August. Her Uncle Auggie disappeared before she was born without leaving a trace. In many ways August is a reincarnation of her Uncle Auggie, both are queer character who ran away to the big city to escape their oppressive family, finding themselves, and love, in the process.

Speaking to the unearthing of queer history, August also finds out the truth of her uncle’s death, and is able to pass the information on to her mother, giving her closure. In the way that time loops go, death, for Uncle Auggie, is not an ending, but an opportunity to come back as August Landry, to have his story known and remembered. His future may not be present, but his memory, his history as a gay man in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, is. He gets to come back in letters, in memory, in honor.

For many queer characters, and by extension, many queer people, the future seems like an impossible, nebulous place where identity and sexuality are still questioned by authorities and governments. One Last Stop is the powerful story of a character who not only fought for a better future in the 70s, but gets to see that future herself, gets to live in that future. She reclaims her space as a queer woman who not only fought for a better world for queer people and communities, but now has the opportunity to see it happen. The book is telling queer people to keep going; the future will be better off for the struggle and riots that are happening right now.

One Last Stop is a story about queer resistance, queer liberation, and persevering in the struggle. When we acknowledge our past, the women, men, and they/thems who fought for queer rights, we can imagine a better future for queer people everywhere. One Last Stop is about breaking out of the struggle, and moving forward, together. There is power in hope, in the next generation of lovers and fighters and queers. There is a better future. And queer people today have the power to make that future a reality.

Linda H. Codega is an avid reader, writer, and fan. They specialize in media critique and fandom and they are also a short story author and game designer. Inspired by magical realism, comic books, the silver screen, and social activism, their writing reflects an innate curiosity and a deep caring and investment in media, fandom, and the intersection of social justice and pop culture. Find them on twitter @_linfinn.