Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

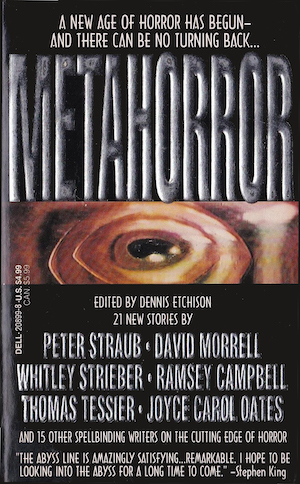

This week, we cover Lisa Tuttle’s “Replacements,” first published in 1992 in Dennis Etchison’s Metahorror anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“How would you feel about keeping a pet?”

Stuart Holder and his wife Jenny are a happy enough modern couple, equal partners who make joint decisions on all important matters. She was a secretary at the London publishing company for which he’s an editor; now she has a senior position at another publishing house, even a company car. He’s always supported her ambitions, but something in her success makes him uneasy, fearful she may realize one day she doesn’t need him. That’s why he picks at her, criticizes her driving. This morning he’s declined her offered ride to the station, a decision he regrets when, amid the street litter, he sees something horrible.

It’s cat-sized, hairless, with leathery skin and a bulbous body propped on too-thin spiky limbs. Its tiny bright eyes and wet mouth-slit give it the look of an evil monkey. It reaches toward him with a strangled mewl; in his terrified rage, he stomps the alien creature to pulp.

Such violence is unlike him; Stuart is instantly sickened and ashamed. When he sees another creature at a street crossing and notices a businesswoman staring in sick fascination, he resists a weirdly chivalric impulse to crush it for her.

In the evening, Jenny arrives looking oddly flushed. She asks how he’d feel about a pet, a stray found under her car. Stuart has a bad feeling even before she opens her bag to reveal a naked bat-thing. How can she call it “the sweetest thing” when his impulse is still to kill it?

Jenny at first thought the creature horrible too, but then realized how helpless it was, how much it needed her. She dismisses Stuart’s objections that it might be dangerous, but agrees to take it to a vet for a check-up.

Though unused to doubting Jenny, Stuart doesn’t believe her report that the vet cleared her “friend” without identifying its species. Jenny holds the bat-thing close to her side, where it looks “squashed and miserable.” She declares that she’s going to keep “him,” sorry if Stuart’s unhappy, but there it is. He tries not to show how deeply he’s wounded. It doesn’t help that she’s sleeping with her pet in the spare room until it “settles in.” Stuart has to hope that her sudden strange infatuation won’t last forever.

Before long he’s fantasizing about how to kill the bat-thing, but when would he have a chance? Jenny never leaves it unguarded, taking it to work and even into the bathroom. Nor is Jenny the only bat-thing obsessive. Stuart’s secretary Frankie now keeps hers in a desk drawer, fastened with a golden chain. Frankie believes other women in the office want to steal the creature, and Stuart catches one of the female editors cooing at it when no one is watching. He orders Frankie not to bring her pet to work, but suspects she’ll disobey.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

One evening he walks in on Jenny nonchalantly feeding the creature blood from an open vein. They both like it, she insists, and she refuses to stop. Like “a dispassionate executioner,” she tells Stuart if he can’t accept her relationship with the bat-thing, he’d better leave.

The couple separate. Stuart moves not far away and sometimes visits Jenny in their formerly shared flat. Jenny never returns his visits. Frankie quits as his secretary and goes to work for a women’s press where, presumably, pets are less unwelcome. He sees an attractive woman on the tube, thinks of speaking to her, then notices she’s carrying a bat-thing chained under her cloak. He never learns what the creatures are, where they came from, or how many there are. There’s no official confirmation of their existence, though there are occasional oblique references.

He wanders, later, past his old apartment. Though curtains are drawn over the windows, he can see the light shining through and longs to be inside, home. Does Jenny ever feel lonely too, would she be glad to see him?

Then he sees a tiny figure between the curtains and window, spread-eagle and scrabbling against the glass. Inside, it longs to be out.

Stuart feels the bat-thing’s pain as his own. A woman reaches behind the curtains and pulls the creature back into the warm room. The curtains close, shutting him out.

What’s Cyclopean: Stuart’s first bat-things stands out, “amid the dog turds, beer cans, and dead cigarettes,” as “something horrible.” Way to set a low bar!

The Degenerate Dutch: Stuart suggests that the animal might carry “foul parasites from South America or Africa or wherever”; Jenny accuses him of being racist. Earlier, he uses some not-so-cute ableist language to describe the bat-thing’s movements as “crippled, spasmodic.”

Weirdbuilding: Tuttle’s bat-things join the weird menagerie along with Martin’s sandkings, Le Fanu’s green monkey, Spencer’s shrimp, etc.

Libronomicon: Jenny compares her new pet to the Psammead, the wish-granting sand fairy from E. Nesbitt’s The Five Children and It.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No madness this week, though plenty of relationships of dubious wisdom and health.

Anne’s Commentary

After reading “Replacements,” I had a nagging sense I’d read something similarly disturbing aeons ago. I flashed on a marriage like Stuart and Jenny’s, one of equal partners, sturdily modern and seemingly content. This happy couple moved to an idyllic New England town and happily discovered many other happy couples. The wives of this town were, indeed, perfectly happy, because they absolutely doted on their husbands, who, being absolutely doted on and submitted to, were also perfectly happy. Of course: The idyllic town was Stepford, Connecticut, fictional setting of Ira Levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives. I read it that year or shortly afterwards, because it was a main selection of my mother’s Book of the Month Club. I surreptitiously read all her BOMC novels that looked “juicy,” which meant Levin impressed me with the fear that husbands were apt to betray their wives by killing and replacing them with robots. Or else by lending their wombs to Satanists for the production of Antichrists.

In addition to two theatrical films (1975 & 2004), The Stepford Wives was made into several TV movies. Revenge of the Stepford Wives saw the women being brainwashed and drugged into submission rather than mechanically replaced. The Stepford Children had both wives and kids replaced by drones. Finally came The Stepford Husbands, in which the men were brainwashed into perfect husbands by an evil female clinician. How come no Stepford Pets? Evil (or saintly?) vet turns dogs and cats into perfectly house-trained and hairball-free wonders. That nonexistent Pets aside, the point is that nobody’s happy with what they’ve got, not if Engineering and Science can produce something better.

The premise shared by “Replacements” and Stepford Wives is that even the most intimate and supposedly durable human relations—our ideals of mutually beneficial and society-stabilizing partnerships—are fragile, makeshift, replaceable. Forget “As Time Goes By,” all that “Woman needs man, and man must have his mate.” What a man really wants is unwavering ego-stroking and obedience; if flesh and blood can’t supply this, give him a comely confection of plastic and circuitry. What a woman really wants is a permanent baby, utterly dependent, so what if it’s a hideous bat-thing. Doesn’t loving something ugly and weak show one’s heart is more noble and capacious than a heart that only responds to beauty and strength?

Or is it closer to the opposite: The heart that responds to utter helplessness and dependency is the egotistical monster?

In Stepford Wives, the monsters are unambiguous: the murderous members of the local “men’s club.” Levin’s plot-driving notion is simple but terrifying if (and this is how thrillers generally work) the reader accepts it for the duration of the novel. Men, self-centered, have no regard for women as persons. They’d much rather have women-objects, female-shaped toys that need no “humoring along.” Say, animatronic wives sufficiently sophisticated to pass for their “selfish” human predecessors. Even “good” men are like this. Even the protagonist’s loving husband, once the Stepford husbands show him the way of true masculine fulfillment.

Who the monsters are in “Replacements” is a more complicated question. Tuttle’s opening provides an obvious candidate: the “something horrible” that Stuart spots on a London street. It’s horrible, all right, but not because it’s dangerous. The opposite’s true—everything about the creature is repulsively pitiable. It’s naked, ill-proportioned, with thin spiky limbs. It moves in “a crippled, spasmodic way.” Its voice is “clotted, strangled,” the aural equivalent of “metal between the teeth.” It goes “mewling and choking and scrabbling” in a way that sickens Stuart. It was “something that should not exist, a mistake, something alien.” Because “it did not belong in his world,” Stuart crushes the creature to pulp. Seeing it’s dead, he feels “a cool tide of relief and satisfaction.”

So who’s the monster in this chance meeting? We could easily pin the label on Stuart, except that his satisfaction gives way to shame, self-disgust, guilt. He encounters another wingless bat-thing at the next street-crossing, noticing it along with a well-dressed woman. His “chivalric” impulse is to kill it for her, but the sick look on her face is one of “fascination,” and he realizes she wouldn’t thank him. He neither wants her to think him a monster, nor does he want to be “the monster who exulted in the crunch of fragile bones.” He’s never hunted, never killed any animal beyond the insect or rodent pests that “had to be killed if they would not be driven away.” Nor is he squeamish or phobic about creepy-crawlies. His reaction to the bat-thing is so uncharacteristic!

But the rage and nausea recur whenever he sees a bat-thing, particularly in association with women, who seem so drawn to the creatures. The worst blow is that wife Jenny grows so infatuated with her foundling bat-thing that she coddles it, sleeps with it, feeds it with her own blood, and ultimately chooses it over Stuart.

Wait, feeds it her own blood? The thing’s a vampire! Yet Jenny’s no victim. She claims she likes blood-suckling the creature. They both like it. Stuart reacts to this as to an admission of adultery. He’s earlier realized the main stressor in their marriage is his fear of Jenny ceasing to need him and becoming too independent. Has the truth been he’s the needy dependent?

Does Jenny replacing Stuart with a more absolute and therefore more satisfying dependent make her something of a monster? None of the bat-things seem to like their female “hosts.” Frankie and the woman from the tube keep theirs shackled to golden chains, so the bat-things won’t get lost—or escape. As Jenny hugs her “friend” close, it looks “squashed and miserable.” Frankie’s gives Stuart “a sad little hiss.” And at story’s close, Stuart and Jenny’s pet prove themselves fellow sufferers in dependence, Stuart longing to get back inside, the bat-thing scrabbling to get back out.

Relationships! Can’t live with them, can’t live without them….

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Wikipedia tells me that British author David V. Barrett called Tuttle’s stories “emotionally uncomfortable,” and you know what, yeah, I’m going to go with that. This is an uncomfortable story—one that leaves me poking at it mentally afterwards, trying to figure it out. It’s also a story that legitimately earns having a male point of view on events that are clearly important to the women involved. But perhaps, for them, not important in the same genre.

Stuart isn’t some terrible narrator who ultimately, thankfully, gets eaten by a grue. He’s a pretty nice guy, a good husband, especially for the early 90s when “career woman” was still a slightly exotic category. Someone who supports his wife’s ambitions, mostly, with only minimal excessive criticism and whinging. Someone who feels really bad about resenting her advancement in their shared industry, and thinks seriously about making up for it. Someone who wants an equal, negotiated relationship. Someone who has never killed anything in his life (except insects and rats, which don’t count) until his first encounter with something creepily other-dimensional—and someone who tries, for his wife’s sake, to overcome that overwhelming revulsion.

Cue the title. How many women, the story suggests, would not want to replace their men with a small, ugly pet that needs them desperately and only sucks a little of their blood?

This is certainly horror, of the quietly-unresolved sort, for the men involved. It seems to be working out reasonably well for the women. What about the replacement-things themselves? They have a pretty good survival strategy going, and yet… there are those chains, which all the women seem to instinctively understand as a requirement. There’s the frequently expressed fear that they might run away. And that last glimpse of Jenny’s creature, scrabbling at the window. The bat-things seem to be victims of their own success. And perhaps, lurking under the critique of what men have to offer, there’s also criticism of how women handle their relationships,.

This is a very late-20th-century sort of a take on gender relations, implicitly binary and heteronormative and low-key separatist. You could fill a whole page with early-21st-century questions that go completely unacknowledged. (Do lesbians share their bloodsuckers along with their bank accounts, or do the bat-things “replace” romantic human relationships of all sorts? Does estrogen mediate vampire-attachment, and if so does acquiring your own wingless extradimensional bat become a key milestone in HRT, and for that matter does one give them up at menopause?) But it works for me anyway, largely because even with these simplifications it’s messy, the picture obviously intended to be incomplete. Stuart never finds out how the bat-things affect much of anything beyond his own relationship, and neither do we.

Much early weird fiction, particularly Lovecraft, hinges on the idea of instinctive revulsion: there are some things so wrong, so alien, that anyone encountering one would instantly want to scream or flee or kill. And that this instinct is correct—that it reflects some genuine badness about the things so reviled. That our unthinking fears and hatreds are trustworthy. Stuart feels just such instinctive hate for the bat-things, but tries to move from hatred to compassion when he sees that someone he loves feels differently. In among all his 90s-nice-guy mediocrity, this is genuinely admirable, and at least some of my readerly discomfort stemmed from the suspicion that his self-enforced compassion would be treated as a mistake. It isn’t, and I appreciated that. The bat-things are certainly, ultimately, bad for him, but no one way of reacting to them is treated as right.

Final note: “Replacements” put me in mind of George R.R. Martin’s 1979 “Sandkings,” with its poorly-understood pets, and the contrast between Stuart’s effort here to be a decent person and Simon Kress’s complete lack of same. I only learned afterwards, reading up on Tuttle, that she and Martin were romantically involved earlier in the 70s as well as occasional co-authors. I’m now curious whether there’s some Frankenstein-like backstory here. Did shared speculation over dinner eventually result in both tales, or did Mary Shelley show up at their door—a sort of reverse person-from-Porlock—and challenge everyone to write about creepy pets?

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 17-18, in which Kara and Simon attempt to deal with the hell dimension that just won’t let go.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.