Let’s get this out of the way: I like David Foster Wallace’s writing. I find value in his craft writing, and I love his “nonfiction” (which, yes, of course it’s not really nonfiction? Did everyone miss the part where writers are encouraged and sometimes even god-willing paid to lie? It’s not like we’re presidential press secretaries for fucks’ sake) and I love all his wild-eyed theorizing about The State Of American Fiction even though a lot of it is outdated and I wouldn’t have even agreed with it while he was alive. Why I love it is that he takes meta stuff and finds the truth and emotion in it. The very thing people roll their eyes out now, the whole idea of “New Sincerity”—to me the fact that he ties ridiculous imagery and winking and meta jokes about authorship to the idea that fiction is supposed to make you feel something, and specifically to make you less lonely, is why people still read it.

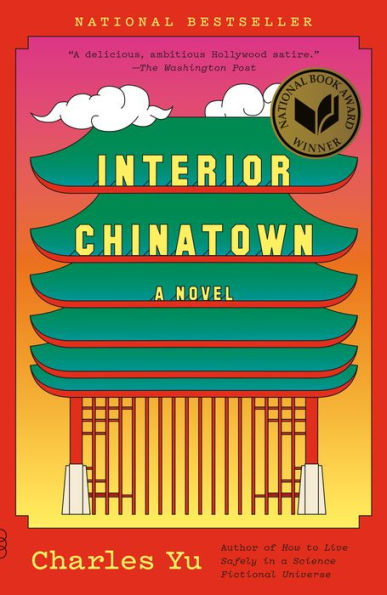

I mention all of this because I think Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown is one of the best examples of metafiction I’ve read since, I don’t know, John Barthes’ Lost in the Funhouse? But, unlike Lost in the Funhouse, Interior Chinatown also intensely moving.

Like “I had to put the book down and walk away from it” moving.

Like, “I am not a person who cries, but I cried,” moving.

The plot, if I can sum it up:

Willis Wu is a young man living in Chinatown. He’s trying to make it as an actor—specifically to work his way up from bit parts to a featured role on a wildly popular crime procedural.

Willis Wu is an extra, living in “Chinatown”—the seedy set for a Black & White, a wildly popular crime procedural. Black & White is also an entire, all-encompassing, Truman Show-esque world. Wu desperately wants to be cast in the only decent role available to Asian-Americans in this TV show that is also life: “Kung Fu Guy.”

Willis Wu is a young American man, the son of immigrants, who desperately wants to live a fulfilling life in a country that refuses to let him be anything more than a stereotype.

Buy the Book

Interior Chinatown

The three layers of the story dance around each other, as extras play “dead” until they suddenly hop up and start talking once the scene’s done…but then after everyone leaves for the day they troop upstairs to the real apartments they live in, above the set that is also a real restaurant. And of course, sometimes the extras die for real, too.

But is it real?

Willis leaves the set after a day’s shoot and is suddenly not in his (real) apartment, but instead in the (…real?) craft services tent, where he bumps into an actor who plays a recurring role, who both is her character but is also an actor. Is the romance between them two actors falling in love? Is it an unlikely meet-cute generated by an exhausted writers’ room? Or is it both.

Willis’ relationship with his parents is similarly layered, especially as it evolves over time. He’s a young boy looking up to his dad, who works as a waiter a restaurant where his mom is the hostess. He’s young boy hero-worshipping his dad, who is a working actor with a bunch of side hustles—until that glorious day when he is cast as Kung Fu Guy, a good role, where he gets to have real scenes and make real money, just like Willis’ mom, who’s often cast as Exotic Asian Woman. A few years later, Willis’ father gets the ultimate, the plum role of Sifu, and his mother is sometimes Dragon Lady. But finally, Willis is a young man desperately auditioning for Kung Fu Guy himself, and now caring for his dad, who aged out of Sifu and has to take demeaning Old Asian Man in A Stained Undershirt roles to pay the bills.

Or maybe Willis’ dad simply works in the restaurant the entire time, but ends up as a fry cook in the back now that he can’t be put on display as a handsome young waiter? And is Willis’ mom still the Hostess? Except…Willis’ dad also used to be an academic, in the South, and he used to be a child who fled a violent coup. Can he be all of those things? Where are the lines between reality and role?

Interior Chinatown could have been a coldly experimental work, a novel-as-exercise. But Yu found a way to go meta while still telling an emotional story, and that was by weaving prose together with script pages. And what this does is…hang on, it’s easier to just show you.

BLACK DUDE COP

Whaddya got?

ATTRACTIVE OFFICER

Restaurant Worker says the parents live nearby. We’re hunting down an address.

WHITE LADY COP

Good. We’ll pay a visit. Might have some questions for them.

(then)

Anyone else?

ATTRACTIVE OFFICER

A brother.

Seems to have gone missing.

Black and White exchange a look.

BLACK DUDE COP

This might a case of—

WHITE LADY COP

The Wong guy.White: deadpan. Black tries hard but like always, he breaks first, flashing his trademark smile. White holds stead a beat longer but then she breaks, too. It’s their show and they have the comfort of knowing it can’t go on without them.

“Sorry sorry. I’m so sorry,” White says, trying to keep it together. “Can we do that again?”

They’ve managed to stop laughing when Black’s nose makes a snort and sends them back into another round of giggles.

Scenes like this flow easily between scripted dialogue and action and the “real” relationship that’s playing out between takes when the cops break character or interact with the director and extras. These behind-the-scenes moments, in turn, flow into Willis’ real life, laid out in blocks of description and second person interior monologue:

INT. CHINATOWN SRO

Home is a room on the eighth floor of the Chinatown SRO Apartments. Open a window in the SRO on a summer night and you can hear at least five dialects being spoken, the voices bouncing up and down the central interior courtyard, the courtyard in reality just a vertical column of interior-facing windows, also serving as the community clothes drying space, crisscrossing lines of kung fu pants for all the Generic Asian Men, and for the Nameless Asian Women, cheap knockoff quipaos, slit high up the thigh, or a bit more modest for the Matronly Asian Ladies, terrycloth bibs for the Undernourished Asian Babies, often shown in montages, and of course don’t forget the granny panties and soiled A-shirts for Old Asian Woman and Old Asian Men, respectively.

Those in turn occasionally drop fully into second-person prose, as when Willis narrates his parents’ lives before they met and had him. Before they came to Chinatown looking for a better life for their child.

I don’t want to say too much more about the plot because I want all of you to read this book and experience it the way I did. Instead, some more thoughts on the structure. I think the thing that worked so well here, and the reason I read it in one sitting, and, as I mentioned cried a few times, is that Yu dances between the script format and more traditional prose like a bee bobbing and weaving between different types of flowers. By slipping from one style to the other, he keeps a reader in a heightened state—the structure allows him to cut to the snappiest dialogue, or, in the prose sections, embed us fully in long, emotional scenes of family life. All the while he can comment on pop culture, storytelling tropes, racist caricatures, whatever, because he can always duck back into his meta conceit when he wants to laser focus the reader’s attention on a particular point or joke.

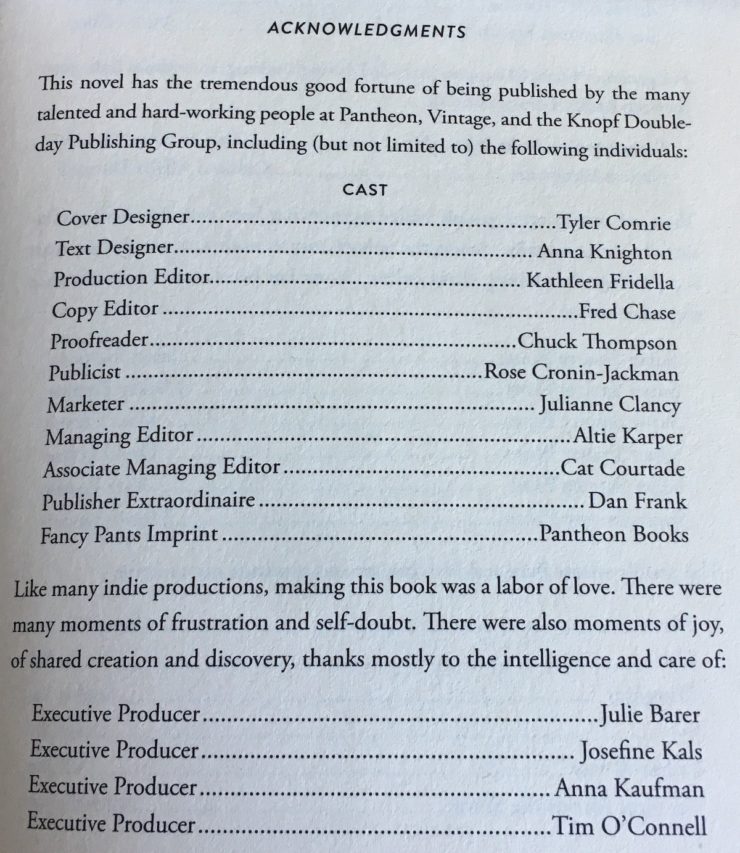

Now, as should be obvious I loved this book, and I admired the way Yu was willing to break out of traditional novel format and tell his story the way it felt right to him, But that all kicked onto a whole other level when I reached the final pages of the book and found THIS:

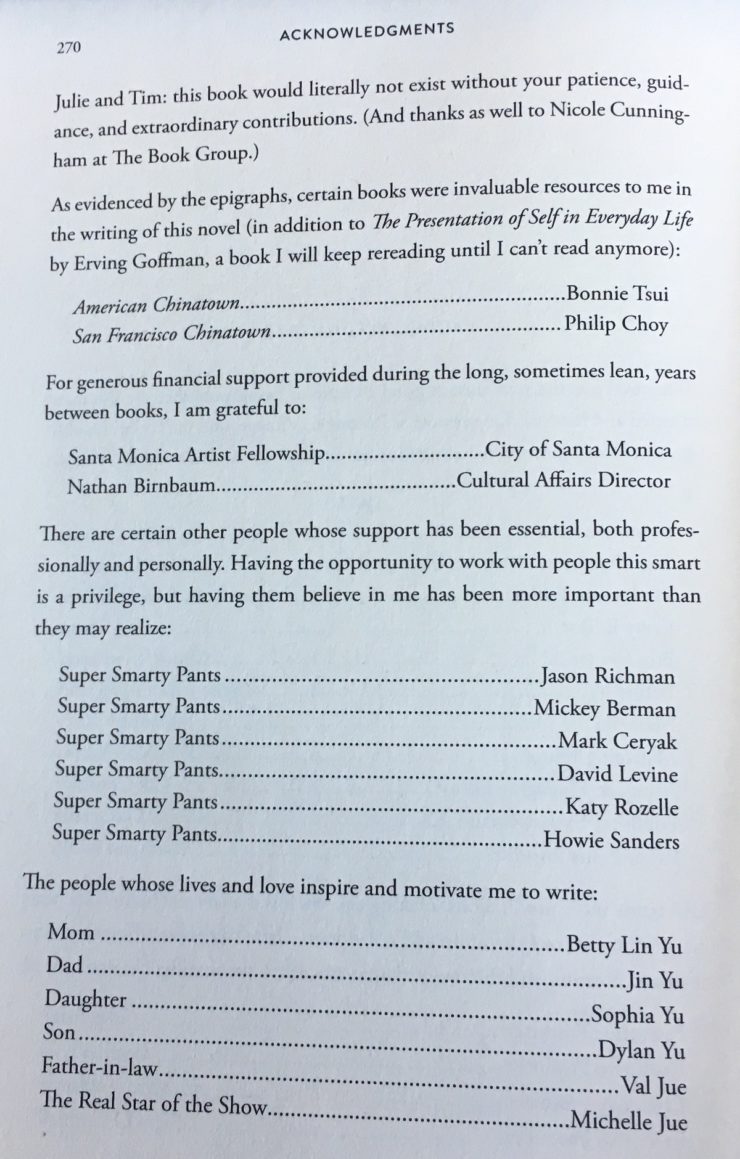

It’s not just that he’s giving credit to the team who worked on the book, which is, itself, classy as hell. But he did it with a credit sequence??? Are you kidding me??? The second acknowledgements page brings the interplay of meta-ness and sincerity to a fitting conclusion:

With Yu closing out his book (and his end credits sequence) by thanking his colleagues and family.

This to me is precisely what meta-narrative is for—to help us examine our emotions and assumptions, to look at the gaps between an artist and their persona, or a writer and their book. Yu uses his innovative structure to critique society and pop culture, but also to comment on the extent to which people are forced to play roles in their lives, whether its for parents, co-workers, or a dominant culture that despises diversity and nuance. And if it just did that this book would be fun, and I’d still recommend it, but I think it becomes truly great because Yu uses his stylistic tricks to disarm his readers and hit them with feelings when they least expect it.

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another shall rise in its place! And they really need to cool it with the derealization. Come join them in the dark carnival of Twitter!