In this scattershot series, we’ll be delving “too greedily and too deep,” prying gems out of the glorious rough that is the extended legendarium of Tolkien’s world. This includes drawing on The Lord of the Rings itself, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, and the History of Middle-earth (or HoMe) books.

Previously, on Tolkien’s Orcs…

I concluded in part 1, which covered the monstrous hoi polloi of Middle-earth as presented in The Hobbit and in The Lord of the Rings, that Orcs are driven to mayhem—and frankly, the will to do anything substantive—by the power of Sauron. Which is to say, when there’s no Dark Lord in the neighborhood to give them some moxie, they become idle (relatively speaking) and their numbers stay down. But what about before all that? What happened before Sauron even became the head honcho of evil?

In this installment, I’m going to look at the role of Orcs in The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, which are like the uber-prequel and the deleted scenes (respectively) to Tolkien’s more famous works. But to fans of the legendarium on the whole, they are also essential reading.

So to recap, we know that between year 0 and year 1130 of the Third Age, the Dark Lord himself was downgraded, too weak to pour any of his get-up-and-go into the Orcs. In his long absence, their presence was small, their evil out of sight, their reach minimal. When he came back, they surged again. But during the War of the Ring, he was defeated again—for realz this time lol—and the Orcs who survived lost all their oomph and were brought to the edge of extinction. All in all, Sauron’s tenure as the Dark Lord spanned about 5960 years, beginning five hundred years into the Second Age and lasting until the end of the Third.

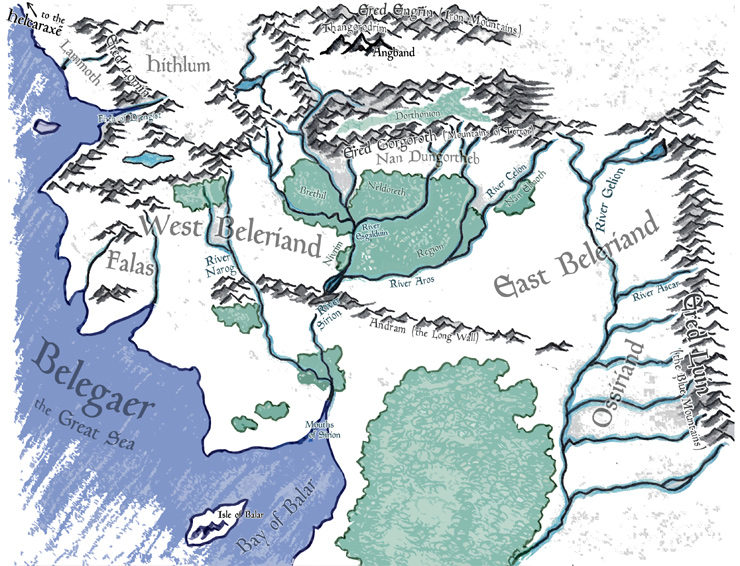

What about the so-called Elder Days? That usually refers to the First Age, and days even more ancient. But before we jump that far, let’s take a brief look at the Second Age, an era that begins in peace and geographic adjustments. The War of Wrath, which marked the end of the First Age, had just ended, and the OG Dark Lord, Morgoth, aka Melkor, had just been ousted. Cataclysmic, collateral damage from that war led to the vast lands of Beleriand sinking beneath the waves of Belegaer, the Great Sea. Then Sauron, Morgoth’s right-hand man, had the opportunity to repent before the Valar, the godlike Powers of the West, but he chickened out and slinked away in shame—troubling no one for about five hundred years.

The Men who’d sided with the Elves in the War of Wrath were rewarded and sent away from Middle-earth, to live on a new island prepared for them far off in the Great Sea…where they prospered and never troubled anyone with their decidedly superhuman skills. Just kidding! They totally went down a spiraling path of bad choices, came back again, subjugated their less-gifted cousins on the Middle-earth mainland, “captured” Sauron himself and roped him into their politics, and finally got their island drowned for it. But before that all played out to its conclusion—a three-thousand-year tale known as the Akallabêth—Sauron also reappeared in Middle-earth and tried to dominate everyone with his Ring-based pyramid scheme. When that didn’t pan out quite like he’d planned, he waged a war on the Elves, Morgoth-style, by using…Orcs!

How? Well, he inherited the office of Big Bad—or rather, actively took up the mantle of Big Bad. He dominated evil creatures, manipulated a whole lot of people (Men, Elves, and Dwarves), and took charge of the Orcs. He’d certainly used them before, though they were never his creations nor even his speciality. That was back when he played second fiddle to Morgoth and was more of a phantoms-and-werewolves guy.

So let’s go back to the earliest of the Elder Days, to…

The Silmarillion

In 1977, Christopher Tolkien published the most complete and consistent version of The Silmarillion, which includes the creation story of the universe (Eä) itself and the world of Arda, but it’s mostly about the Elder Days, the ancient dramas of Elves and Men vs. the original Dark Enemy of the World: Morgoth. This is the saga that Tolkien had wanted to release for most of his life but (a) he never was able to convince his publishers to accept it and (b) he never quite finished it to his satisfaction. Nevertheless, Tolkien kept tinkering away with it, and so there are different events, versions, and even modes of these stories—most of which make it into the History of Middle-earth series. If you don’t know much about this book, I obviously recommend it. And I did say one or two words about it in The Silmarillion Primer series.

So herein we learn that Orcs are made from some of the first Elves who appeared in Middle-earth by the lake of Cuiviénen hundreds—maybe thousands—of years before the appearance of mortal Men, not to mention the Sun itself. The Elves are considered the Firstborn of the Children of Ilúvatar, and they are “awakened” into existence under a star-lit sky. Sometimes they are called the Eldar (“children of the stars”) and sometimes the Quendi (“those that speak with voices”).

But the ex-Vala, Melkor (who would later be named Morgoth), discovers the Elves before the Valar do. He sends mysterious servants, “shadows and evil spirits” to elfnap some, and they’re brought back to his fortress of Utumno. Utumno is evil to the core, worse than Mordor; it was built in darkness before the Sun and Moon, before the Two Trees of Valinor were even a thought, during truly ancient times when Arda’s principal source of light were two gigantic lamps.

Now, Utumno is like a monster factory in the far, far north of Middle-earth. Like a foundry—nay, a PEZ Dispenser—of villainy. Melkor had first gathered his Balrogs there during his salad days of marring Arda. In the Sindarin tongue, Utumno is known as Udûn (of “The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn” fame), and it’s the place where he’d already been building his own forces, breeding “many other monsters of divers shapes and kinds that long troubled the world.” So it makes sense that it’s in this literal hell on earth that the captured Elves…

were put there in prison, and by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus did Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes. For the Orcs had life and multiplied after the manner of the Children of Ilúvatar; and naught that had life of its own, nor the semblance of life, could ever Melkor make since his rebellion in the Ainulindalë before the Beginning; so say the wise.

So it’s firmly established in this version of Middle-earth that Orcs come from Elves, period. No mention of Men being in any way involved. Indeed, the Secondborn of the Children of Ilúvatar won’t even exist for a very long time yet.

Now, while Orcs are formed from elven-stock, it’ll be a very long time before Elves actually find out about them—and even then, they don’t even know precisely what they are. In fact, while Orcs are first bred in Utumno and under Melkor’s direct supervision, he himself won’t even be on the world stage when they’re field-tested that first time. Bummer for him.

See, after the Valar finally discover that Elves have arrived and are milling about Middle-earth, they make the big decision to deal with the Melkor problem; sadly, missing the fact that he’d already found them and even swiped some for his use. So the Valar invade Utumno and haul Melkor away in chains. But in the process they don’t discover all the “mighty vaults and caverns hidden with deceit far under the fortresses of Angband and Utumno.” In the aftermath, evil things (i.e. Orcs and other unnamed monsters) are “dispersed” and scattered elsewhere to wreak havoc another day. Melkor himself is placed in solitary confinement in the Halls of Mandos. Meanwhile, that centurion of evil, Sauron, evades capture and holes up in Angband, which is like a back-up Utumno: a “fortress and armoury not far from the north-western shores of the sea.”

This being the general layout of Beleriand around this time, with Angband way up north.

So the point is, Melkor’s not in the picture when, in his absence, someone first lets the Orcs out!

And it’s actually Dwarves who meet them first. We learn this not from any firsthand account but from the fact that the bearded folk share the news with their earliest Elf-acquaintances in Beleriand: the Sindar, or Grey-elves. Orcs might have got their start in Utumno, but they’ve been dispersed to somewhere in the east, in Eriador or beyond:

And ere long the evil creatures came even to Beleriand, over the passes in the mountains, or up from the south through the dark forests. Wolves there were, or creatures that walked in wolf-shapes, and other fell beings of shadow; and among them were the Orcs, who afterwards wrought ruin in Beleriand: but they were yet few and wary, and did but smell out the ways of the land, awaiting the return of their lord. Whence they came, or what they were, the Elves knew not then, thinking them perhaps to be Avari who had become evil and savage in the wild; in which they guessed all too near, it is said.

Who are the Avari, that Orcs could be mistaken for them? To Elves like the Sindar (and others who traveled across the Great Sea to Valinor), the Avari are like unenlightened cousins who lived out east and from whom they’ve become estranged. Called the Unwilling, they were those Elves who never had any interest in answering the summons of the Valar. The Avari aren’t bad—and in fact the Wood-elves of The Hobbit include Avari among their ancestors—but they just don’t factor into the primary dramas of Middle-earth (which begins in Beleriand and moves later into Eriador and Rhovanion).

Still, that the Elves of Beleriand think that Orcs they encounter might be “savage” or degraded versions of their own kind is ironic and fascinating! It makes me wonder what physical characteristics Orcs and Elves are supposed to have in common—aside from two arms, two legs, and a head?

I often wonder: Who was running the horror show in Melkor’s absence, and who was it that loosed the Orcs? Very probably Sauron, though it could be any of Melkor’s top servants overseeing R&D, which is now fully based in Angband. But wolves, creatures that walk in “wolf-shapes,” and “other fell beings of shadow” all definitely have Sauron’s fingerprints, too. We’re talking wargs and werewolves—long before he becomes even the second Dark Lord and famous ringmaker, he is a sorcerer, a “master of shadows and of phantoms, foul in wisdom, cruel in strength, misshaping what he touched, twisting what he ruled, lord of werewolves.”

But in due time, Melkor does get released from his prison in the Halls of Mandos. Then, yadda yadda yadda, he returns to Middle-earth. And now he’s straight-up called Morgoth, the Dark Enemy of the World, accessorized with a black crown of iron inlaid with the much-ballyhooed Silmarils. He lifted those without permission!

Morgoth settles permanently into Angband, renovating as needed, and raises up the three volcanic and decidedly metonymic peaks of Thangorodrim above it. Cracking his knuckles, he gets to work doing what a Dark Lord does: making everything worse for everybody.

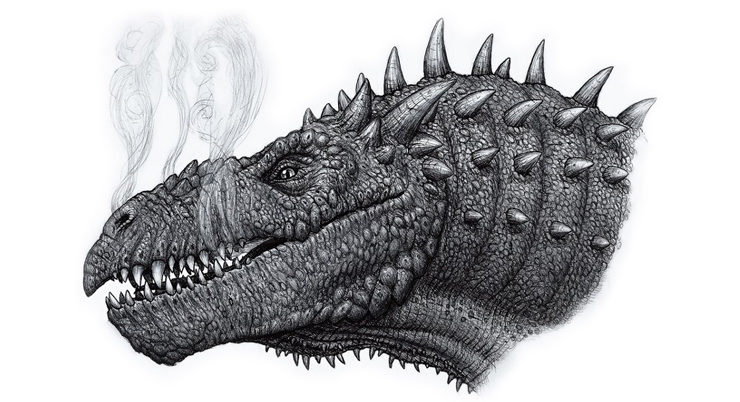

Now the Orcs that multiplied in the darkness of the earth grew strong and fell, and their dark lord filled them with a lust of ruin and death; and they issued from Angband’s gates under the clouds that Morgoth sent forth, and passed silently into the highlands of the north.

We know that word “fell” all too well from The Lord of the Rings, where it is usually applied to the Nazgûl or to beasts corrupted by Sauron. We don’t usually see it applied to Orcs directly like this. But we do so here. Let’s remember that for later; it seems like these early Orcs are much more dangerous than, say, Mordor pals Gorbag and Shagrat.

Now, this was the first of the big Wars of Beleriand, and it goes well for Morgoth, all things considered. His Orc armies eventually get routed, and even Dwarves join in the fun. But the Elves suffer major losses; their victory is “dear-bought,” and it establishes a new normal for the Elves in Beleriand. No longer could they just go about in peace. They had to shore up, fence themselves in, get organized, and stay out of the vast wilds, where “the servants of Morgoth roamed at will.”

But not long after that, the Moon rises for the first time. Then the Sun! The world is flooded with light.

This move on the part of the Valar is one that Morgoth had not foreseen. And it’s an unpleasant new paradigm for the Orcs, for they greatly dislike this Sun business. It’s not in their DNA to easily ignore such overarching light. It’s not like firelight; they’re used to that. It comes from the same source that the holy light of the Silmarils did—cultivated from the last golden fruit of Laurelin, one of the Two Trees of Valinor. Morgoth had thought he’d taken care of those!

At one point, we’re told “the dread of light was new and strong upon the Orcs.” Yet it doesn’t burn them up. It’s more of a demoralizing effect, and there will be plenty of occasions where Orcs wage war day and night. Because what choice do they have?

I won’t itemize every place in the text that Orcs show up in The Silmarillion, but I do want to address some key points. They are, after all, the meat and potatoes of Morgoth’s armies, even when dragons pop up, werewolves come running in, or Balrogs hog the spotlight. They’re the first to kick off violence and are present in each of the famous Wars of Beleriand. Elves win plenty of victories over them—especially when the Noldor are on the scene—but Morgoth just keeps breeding more. Since they multiply “after the manner” of Elves and Men, there surely are Orc-women and Orc-babies somewhere underground and in mountain caves, and for all we know Orc-females are part of the hordes marching to war. As the Tolkien Professor, Corey Olsen, once put it:

I would also not be surprised if there were Orc women fighting in the armies alongside the men. This is just a guess on my part, but it’s hard to imagine that Orc women would not be equally as savage and ferocious, and their bosses are not exactly chivalrous. Obviously the higher-ups like Sauron and Morgoth want a continually growing Orc-population as the top priority, but I have to think that the women were often used in battle, too.

Whatever society they may have simply exists under the boot of Morgoth himself, so it’s hardly natural. More important, we’re told this:

And deep in their dark hearts the Orcs loathed the Master who they served in fear, the maker only of their misery.

Knowing this far back in time that Orcs hated their own boss brings Gorbag and Shagrat to mind. Ignorant of just how much their identities are tied to the Dark Lord, they would still prefer to operate away from the Great Eye. But still, Orcs do obey their masters, whoever they are. They have to, when that immortal will is bent upon them. They kill and they capture and they torment others.

Still, in The Silmarillion, once the exiled Elves cross over to Middle-earth and start setting up camps and kingdoms, Morgoth has to get sneakier. See, after one of his first failed assaults against the Elves, one meant to test their strength, he pauses.

Morgoth perceived now that the Orcs unaided were no match for the Noldor; and he sought in his heart for new counsel.

He needs new tactics. Yeah, he would rather just throw Orcs at his problems. But his problems are mostly the Noldor, vengeful Elves he pissed off back in Valinor when he killed their high king and stole their beloved Silmarils. Now they’re back on Middle-earth, “new-come from the Blessed Realm, and not yet weary of the weariness of Earth.” These Elves aren’t comparable, say, to the Silvan Elves of the Woodland Realm in The Hobbit. For a variety of reasons, they’re better armed, better trained, and juiced with the light of the Two Trees. So just deploying Orcs isn’t going to do it. It can’t just be a numbers game, if Morgoth wants to win. He needs the element of surprise and the kind of strength that can only be built over time.

Well, he gets that with the Dagor Bragollach, the Battle of the Sudden Flame hundreds of years later—in fact, midway through the fifth century of the First Age (counting from year 0, at the rising of the Sun). He has been patient, and it will pay off.

Morgoth’s solution = numerous volcanic eruptions that ravage the land + the proper unleashing of Glaurung, the first dragon + Balrogs + more Orcs than were ever loosed before.

Morgoth had allowed the Noldor to grow complacent, to believe they’d had him contained. This war is a victory for Morgoth, but he doesn’t wipe out the Elves entirely; in fact, by this point in time, the Secondborn Children of Iluvatar, Men, had wandered into Beleriand. Elves now have some Men in their corner. Morgoth just doesn’t take them seriously… yet.

Now that Morgoth’s got Elves on the run, he sends his Orcs out to freely harass all the lands of the North, and they successfully capture many Noldor and Sindar. These Elves become thralls in Angband and are put to work. Morgoth even uses their own past sins against then to sow doubt among the remaining un-captured Elves.

But ever the Noldor feared most the treachery of those of their own kin, who had been thralls in Angband; for Morgoth used some of these for his evil purposes, and feigning to give them liberty sent them abroad, but their wills were chained to his, and they strayed only to come back to him again. Therefore if any of his captives escaped in truth, and returned to their own people, they had little welcome, and wandered alone outlawed and desperate.

Here he has them under his power, and to me it raises an interesting question. This is Angband we’re talking about, as much a workshop as a dungeon, and it’s Morgoth running the show. Why is there no talk of new Orcs being made from his captive Elves? Isn’t that how he made them in the first place? Couldn’t he start fresh, this time maybe taking into the account the damned Sun?

Though not specifically addressed, I think it’s implied that Morgoth can’t restart Project Orc from scratch anymore. For one, by this point he’s squandered too much of his power corrupting and marring Arda. For example, he cannot change his own form anymore, can’t go about “unclad” and Casper-like through walls. He’s locked in a physical, if mighty body. It might also be that Elves are simply stronger and wiser now. They aren’t so young and malleable, as they were by the shores of Cuiviénen at the time of their awakening, with only the stars and the natural world to learn from. They’ve already met the Powers of Arda; some have seen the light of the Two Trees of Valinor with their own eyes. The “slow arts of cruelty” aren’t going to remake them now. Which is not to say that cannot be tormented and broken.

Still, no more Orc-making. Obviously more Orcs are bred, but presumably only from the existing generation. Sure, we’ll see new varieties bred in later ages—Black Uruks of Mordor, for example, or the Misty Mountain goblins, or Saruman’s own Uruk-hai. But these are all still copies of copies of the original stock of Elf-wrought Orcs. Like Multiplicity, but for Orcs.

Anyway, what else do Orcs get to see and do in The Silmarillion?

Well, they certainly participate in the tale of Beren and Lúthien. Starting with the death of the hero Barahir and his band of unmerry Men, who had made such a nuisance of themselves against the minions of Morgoth in the highland region called Dorthonion. In fact, the Orcs that take him down operate under the command of Sauron, who was tasked to see it done. After killing the outlaws, the one survivor—Beren, Barahir’s boy—follows them to their camp.

There their captain made boast of his deeds, and he held up the hand of Barahir that he had cut off as a token for Sauron that their mission was fulfilled; and the ring of Felagund was on that hand.

Here we see that while Orcs have their orders, they are petty enough to seek prizes of their own and brag about their accomplishments. One could argue that this sort of maiming and looting is all Orcs have to look forward to. And sometimes even that is denied. It’s not like this captain is going to be allowed to keep that fancy ring. The ring will surely be surrendered to his boss, the lord of werewolves, and I bet Sauron has a thing for jewelry. Now, will Sauron commend this Orc-captain for a job well done, or give him a promotion, stock options, and greater responsibility? Will he get a glowing end-of-year review? Or will he just stay off Sauron’s feed-to-werewolves list again this year?

Anyway, this ring will someday be worn by Aragorn son of Arathorn. It was given to Barahir years before by the meritorious Finrod Felagund, Galadriel’s big brother (and Elf-king of Nargothrond). And yet, after all that, the Orc-captain’s boasting is all for naught. Beren gets his revenge by killing the lot of them, then goes all Rambo on other servants of the Dark Lord in the region. Tales of Beren’s exploits against the minions of Angband spread far and wide, and this clearly makes Morgoth look like a chump:

At length Morgoth set a price upon his head no less than the price upon the head of Fingon, High King of the Noldor; but the Orcs fled rather at the rumour of his approach than sought him out.

Two fascinating bullet points pop out from that passage.

- Morgoth sets a price on the heads of certain people! Does this mean he has some kind of reward system? Everywhere else it seems clear that he rules through fear, not respect. Does…does Angband have incentive programs? Cushy retirement packages dangled like carrots for exemplary evil deeds or lifetime achievement awards? Of course, if Morgoth implemented such a system, you know it’s a ruse: Morgoth hates everyone, even his Orcs. They were made in mockery and envy of the Elves. I do wonder if that “price” is extended to those beyond his immediate realm. Other outlaws among Men, or even Dwarves? Who would accept that bounty?

But, look, I get it. Sometimes dark lords have to outsource their bounties when their own officers and orc-troopers can’t get the job done.

- So Beren’s presence fills the Orcs with so much dread that they flee from him. That’s really saying something. It is the power and malice of Morgoth which fuels them, yet here they are, afraid of one mortal Man lurking just beyond the doorstep of Angband itself. It seems Morgoth’s hold over Orcs is not absolute.

Later, there are some Orcs in Morgoth’s court during Beren and Lúthien’s infamous jewel heist. Now, The Silmarillion doesn’t explicitly mention them there in Morgoth’s “nethermost hall,” but I mention Orcs in attendance for when they come up in the History of Middle-earth books (which I’ll talk about next time). And likewise, given that Orcs are still the majority population in and around Angband, lots of them are certainly slaughtered by the great werewolf Carcharoth soon after, when he goes on a rampage and “slew all living things that stood in his path,” what with the searing power of the Silmaril in his belly. All in all, this whole event is an embarrassing low point for Morgoth.

Still, he saves face some years later when we come to the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, or Battle of Unnumbered Tears, so named “for no song or tale can contain all its grief.” This time, on top of the usual Orc legions and Balrogs, we get trolls, wolves, wolfriders, and dragons. That’s plural dragons because Glaurung the golden was called “father of dragons,” after all. Here it’s the full might of Angband, and yet we’re told that still wouldn’t have been quite enough to achieve the end of the Noldor and their allies.

Rather, the evil straw that broke the Elvish camel’s back was “the treachery of Men.”

Well, shit. That’s us. As Morgoth designed, a whole bunch of Men turn on their Elf allies at a critical moment (not all do, but enough). So that vast battle is a resounding victory for Morgoth and his Orcs, and it wins them the famous Húrin of the House of Hador as a captive. This bondage kickstarts the whole Children of Húrin tale, discussed more in Unfinished Tales and, better still, The Childen of Húrin book. Still, the good guys aren’t entirely wiped out in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears, but the losses are extreme.

Later, Orcs get to join the dragon Glaurung when he leads the charge in the sacking of Nargothrond, in the tale of Túrin Turambar. They drive off and kill the Elves of that defensible-at-least-until-Túrin-came-along riverside fortress, then chain up the “women and maidens that were not burned or slain,” carting them off to be slaves. But when the siege is all over, the Orcs—far from home and without the direct oversight of Morgoth—try to help themselves to the spoils. We’re talking the loot of the Nargothrond and the treasures of Noldorin Elves. This is the good stuff! But Glaurung denies the Orcs, covetous dragon that he is, “even to the last thing of worth.” He drives them away, scooping up all the riches of Nargothrond around himself to lay upon. Orcs often get the short end of the stick.

Later, it’s also Orcs who capture the traitorous Maeglin, nephew of the Elf-king Turgon, which is a huge win for Morgoth since it yields him the location of the hidden city of Gondolin. Then Orcs pad the invading armies that sack it: another red-letter day for the Orcs. (Well, for those who survive the siege.) Yeah, Balrogs and dragons upstage the Orcs as usual, but without the shock troops, without the Orc-legions, the Dark Enemy of the World wouldn’t have been able to achieve much. Some Orcs even bear witness to the escaping Gondolin refugees and the great battle between Glorfindel and a Balrog. Of course, they fail to report any of this to Morgoth, what with the great eucatastrophic Eagles swooping in and dropping said eyewitnesses from high places. Every last one of them.

At the end of the First Age, when the aid of the Valar is at last beseeched by Eärendil the Mariner (Elrond’s dad!), the War of Wrath takes place. The Lords of the West send their great force over to Middle-earth to take care of the Morgoth problem once and for all. In response, the full might of “the Throne of Morgoth” is unleashed out of Angband. No holds barred, no Orcs deliberately spared. Orcs may be the least powerful of his minions but they’re still the most numerous. And he backs them up with every kind of monster he’s got.

The War of Wrath is vast and epic and Tolkien is frustratingly scarce on details. The host of the Valar sweep in, “in forms young and fair and terrible,” and the ground trembles. The war tramples Beleriand. We’re told that all but a few Balrogs are slain…

and the uncounted legions of the Orcs perished like straw in a great fire, or were swept like shrivelled leaves before a burning wind. Few remained to trouble the world for longer years after.

Few, not none. Someone’s got to keep them going. So the Orcs that do survive—to flee into mountain holes outside of sinking Beleriand—are those that, centuries later, Sauron will come forth and command. Or, more likely, their descendants, for we don’t know how long Orcs would live if they are not taken out with violence.

But when Morgoth’s forces are defeated, in his most desperate hour, he brings out his final ace: winged dragons. This actually stalls his final groveling defeat for a little while.

But his end is inevitable, and in chains he’s dragged out of Angband, out of Middle-earth, and out of Arda altogether: The Valar show him the door, then make sure it hits him on the way out. Beleriand’s a sinking mess, and so many have been slain. The Elves are not so numerous now. The final defeat of the Dark Foe of the World comes at a dear, dear price.

Then comes the Second Age, where things calm down for a time. Concerning Sauron, we’re told that around the year 500 . . .

those who perceived his shadow spreading over the world called him the Dark Lord and named him the Enemy; and he gathered again under his government all the evil things of the days of Morgoth that remained on earth or beneath it, and the Orcs were at his command and multiplied like flies.

Then follows the well-known stories of the Rings of Power and the multiple defeats of Sauron before his last hurrah at the end of the Third Age. Before I move on to the next book, here’s one last little tidbit. In the Appendix under “Elements in Quenya and Sindarin Names,” there is an entry for hoth, a Sindarin word meaning host or horde. In the main text we see this in words like Tol-in-Gaurhoth, the island-tower that Sauron seized and renamed in the First Age. It basically means “tower of the werewolf horde.” But we’re also told, quite incidentally, that Glamhoth is a name the Elves use for Orcs overall, and it means “din-horde.” Din as in loud noise. Remember this name: Glamhoth!

Glam = loud/confused noise

hoth = horde

dring = beat or strike (as in Glamdring, the foe-hammer)

Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth is a 1980 publication; it’s the first behind-the-scenes expansion material that Christopher Tolkien released after The Silmarillion. The book contains a handful of stories and essays regarding events of the First, Second, and Third Ages. They are, as he wrote, “elaborations of matters told more briefly, or at least referred to, elsewhere.” There is nothing entirely new about Orcs in this book—neither their origin or their nature—but I would like to tease out a few scraps of lore.

The first few stories are based in Beleriand, like much of The Silmarillion, before that whole region gets crumbled into the Great Sea.

In the Unfinished Tales account “Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin,” we see that after the resounding success of the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, Morgoth is on a roll. He sends out Orcs to capture any Elves they can, not to kill but to capture and enslave. This leads to the Grey-elves of Mithrim hiding out in caves, and it is they who foster the orphan Tuor, son of the war hero Huor. Tuor famously meets one of the Valar face to face (shout-out to Ulmo!), as no Man ever has, and goes on to bring warning to the hidden city of Gondolin of its prophesied doom. This, sadly, doesn’t spare the city its eventual fate. But Tuor’s presence at least provides some of its people the chance to escape ruin with a glimmer of hope, plus serves as a catalyst to the heroism of others: Idril, Ecthelion, Glorfindel, Eärendil, et al.

Anyway, this narrative goes into greater detail than The Silmarillion does regarding Tuor’s adventures. On his grueling hike through dragon-defiled lands during a supernaturally harsh winter in search of Gondolin, Tuor and his companion encounter a camp of Orcs sitting around a fire on the road. Blocking his immediate path.

‘Gurth an Glamhoth!’ Tuor muttered. ‘Now the sword shall come from under the cloak. I will risk death for mastery of that fire, and even the meat of Orcs would be a prize.’

First, there’s that word Glamhoth again—the din-horde—and we’re shown that it can also be translated as “host of tumult.” Since he was raised by Elves, Sindarin is essentially Tuor’s first language; no surprise he is quick to curse with it: Death to the din-horde! Second, I sure hope “the meat of Orcs” means the meat of beasts acquired by Orcs.

Now, Tuor’s companion is an Elf-mariner named Voronwë, who knows that Orcs are more of a problem than just the ones you see in front of you. They’re the din-horde for a reason. Moreover, the sharp-eyed Elf spots other campfires in the distance that his mortal friend cannot.

‘A tumult will bring a host upon us. Hearken to me, Tuor! It is against the law of the Hidden Kingdom that any should approach the gates with foes as their heels; and that law I will not break, neither for Ulmo’s bidding, nor for death. Rouse the Orcs, and I leave you.’

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

In The Silmarillion, Voronwë is a pitiable but likeable hermit when we meet him; sad but noble, long separated from his people. But here he is also a cunning and wise companion, the perfect foil to Tuor’s more direct, simmering, wrathful approach. To me this moment recalls the proverbial exchange between the two Men of the Fellowship two ages later:

‘Then let us start as soon as it is light tomorrow, if we can,’ said Boromir. ‘The wolf that one hears is worse than the orc that one fears.’

‘True!’ said Aragorn, loosening his sword in its sheath. ‘But where the warg howls, there also the orc prowls.’

Where you see one foe, there are sure to be others. Especially with Orcs! Even when you’re trying to be stealthy. Pick a fight with one, you’re picking a fight with all in the vicinity. Alert one, those noisy bastards will alert the rest. Put another way, if you drop even a stone down a well in one chamber, you might just get attacked by Orcs in the Chamber of Mazarbul a while later!

Remember how in The Lord of the Rings there are little tracker Orcs with “loud and snuffling nostrils?” I’d say we’re seeing some of their ancestors here, for despite their best efforts, this First Age Elf and Man (both races at the top of their game) are scented and heard by the Orcs, and are forced to make a desperate escape. Only with the help of a magical concealing cloak given to Tuor by Ulmo, the Lord of Waters, are the two able to get away.

In “Narn i Hîn Húrin (The Tale of the Children of Húrin),” the famous mortal Túrin Turambar kills a lot of Orcs (and also, unfortunately, friends) during his adventures. As usual, Orcs comprise the warbands and armies sent out by Morgoth in Beleriand at large. But at one point the father of dragons, Glaurung the Golden, sets himself up as “dragon-king” in the sacked Elf-city of Nargothrond, and he gathers Orcs to him. Previously, he’d sent them away without a single bauble from the treasures of the Elf-city. But now he’s become their general. I do wonder: Does he let Orcs quarter in the halls themselves or must they camp out of doors above the underground city? No way they get to hang out in his bedroom/treasure chamber.

Both Sauron and now Glaurung get to command their own armies. It seems not to bother Morgoth that subordinates take charge of Orcs from time to time. Well why not? Their malice is still bank-rolled by him, the first and greatest Dark Lord. Hell, he signs all these folks’ paychecks!

Later in the tale, while Túrin is living his best life with the woodsmen of Brethil and settling down with a…well, let’s just say a wife (it’s complicated), the rumor of some of that din-horde coming into the region nearly spurs him to go on the hunt again. These are Orcs of Glaurung’s dominion, too. But Túrin’s sis…err, wife, convinces him to stay put; the Orcs haven’t arrived yet. Then we get this tantalizing nugget:

But the woodmen were worsted, for these Orcs were of a fell breed, fierce and cunning, and they came indeed with a purpose to invade the Forest of Brethil, not as before passing through its eaves on other errands, or hunting in small bands.

This kind of talk makes me sit upright and search for more info. A fell breed! The implication that previous breeds of Orcs were not so bright, and were less fierce, is intriguing. Does Tolkien ever address different strains of Orcs of the First Age? Sadly, no! GAH.

There is no talk of Orcs in Unfinished Tales concerning Númenor, not because Númenóreans didn’t clash with the din-horde (they surely would have during some of their Middle-earth conquests!), but because the stories in this book concern the island itself, its lineages, and even its tragic romances. And there’s no way a single Orc set foot on that mythic island.

Next: In the expositionally tangled but fascinating chapter “The History of Galadriel and Celeborn,” Orcs play their usual part, forming the armies of Sauron in his Second Age and Third Age wars against the Elves. Then comes the waking of Durin’s Bane, the Balrog.

Nevertheless, it was not until the disaster in Moria, when by means beyond the foresight of Galadriel Sauron’s power actually crossed the Anduin and Lórien was in great peril, its king lost, its people fleeing and likely to leave it deserted to be occupied by Orcs, that Galadriel and Celeborn took up their permanent abode in Lórien, and its government. But they took no title of King or Queen, and were the guardians that in the event brought it unviolated through the War of the Ring.

From this, of course, we see what prompted Galadriel to become the Lady of the Golden Wood that we know and love. It wasn’t necessarily a given that she would rise to great political influence and govern her own realm (despite her origin story and her pride). It seems the threat of Orc squatters in Lórien factored into the power vacuum.

But long before Galadriel and Celeborn assumed leadership in Lothlórien, there was . . .

“The Disaster of the Gladden Fields,” the incident that leads to Isildur’s loss of both the One Ring and his own life. By Christopher Tolkien’s admission, this narrative was written “in the final period of my father’s writing on Middle-earth,” so the details it provides might deviate from Tolkien’s thinking at the time of writing The Lord of the Rings itself. In any case, at the time of this account, Sauron is dead. Dead as a doornail, for all the good guys can tell. Isildur pocketed that valuable bit of jewelry—ostensibly claiming it as “weregild” for the deaths of his father and brother—only two years before. And sure, we know the basic story from LotR: Isildur is marching north along the east banks of the Anduin River and is attacked by Orcs. He jumps into the water, but the Ring betrays him and slips free, the Orcs shoot him, and so Sauron’s prize is lost to all for a very long time.

But let’s back up. Why do Orcs waylay this group of random well-armed Men from Gondor? Are we to suppose they, Orcs of the Misty Mountains, would recognize Gondor’s new king? Well, these are the fun details that Unfinished Tales dishes…

First, it’s a forty-day journey from Osgiliath to Rivendell, which is where Isildur is headed, specifically seeking the advice of Elrond and also missing his wife and youngest son (who’d been safely kept there during the war with Sauron). The disaster at the Gladden Fields is no stealth attack but a riotous ambush. The “hideous cries of Orcs” precedes their actual charging numbers. You’d think they’d want to lead with hidden snipers alone, but hey, they don’t call them the din-horde for nothin’!

Now, the good guys might be Dúnedain clad in Númenórean armor, but they’re ten-times outnumbered by these Orcs and the terrain isn’t favorable. Isildur calls it, stating that there is “cunning and design” in the attack. He and his soldiers beat back the initial assault, and Isildur thinks maybe the Orcs might retreat for good, believing that it’s their way to be “dismayed when their prey could turn and bite.”

But he was mistaken. There was not only cunning in the attack, but fierce and relentless hatred. The Orcs of the Mountains were stiffened and commanded by grim servants of Barad-dûr, sent out long before to watch the passes, and though it was unknown to them the Ring, cut from his black hand two years before, was still laden with Sauron’s evil will and called to all his servants for their aid.

Had the Dark Lord been truly destroyed (as they thought) and his Ring unmade, these Orcs wouldn’t even have left the mountains at all, much less chosen to tangle with Númenórean knights. But this is a trickling down of power and of great evil. The Ring still exists, and therefore so does the malice of Sauron. Though he himself is too diminished to direct—or indeed even be aware of this attack—the Orcs are acting on old orders given to them by scary-ass commanders of the Dark Tower. The enduring power of the Ring sees it through. It calls to them.

An endnote points out that before the final battle at the gates of Mordor, Sauron had sent out “such Orc-troops of the Red Eye as he could spare” specifically intending to hinder crossings of Elves and Men through the Misty Mountains. They only attacked groups they outnumbered, so they hadn’t been able to stop Gil-galad and the greater armies of Men when they’d crossed with the Last Alliance years earlier. But this particular group of Orcs?

It is unlikely that any news of Sauron’s fall had reached them, for he had been straitly besieged in Mordor and all his forces had been destroyed. If any few had escaped, they had fled to the East with the Ringwraiths. This small detachment in the North, of no account, was forgotten. Probably they thought that Sauron had been victorious. . .

So they just hadn’t gotten the memo.

This story provides so much more insight into the attack itself, its aftermath, the character of Isildur (he doesn’t just jump into the water at the start of the attack), and how the shards of Narsil eluded capture. But that’s not all so much about the Orcs. Even though they were victorious here, nearby Woodsmen (mortal men) alert Thranduil’s people, so Elves chase off the Orcs before they can (a) mutilate all the fallen and (b) potentially hunt down survivors (who can report the whole event).

Still! Think how weighty are the circumstances brought on by these Orcs “of no account” coming out of the hills and attacking.

- The timing: Isildur on his way to Elrond in Rivendell with the Ring, open to the idea of giving it up!

- The location: As Isildur says, “Moria and Lórien are now far behind, and Thranduil four days’ march ahead.”

This leads to both the good guys and the Enemy losing all knowledge of the One Ring. The loremasters of Rivendell learn just enough about it (and safely guard the heirlooms of Isildur) but not enough to do anything but wait until “chance” brings matters together again. The stage is now set for Sméagol…some 2,561 years later.

Now, Tolkien’s history doesn’t record many Orc personalities, and the only named Orc in Unfinished Tales is Azog in “The Quest of Erebor.” He was originally name-dropped by Thorin in The Hobbit. He’s that great Orc of the Misty Mountains, father of Bolg and the killer of Thrór (King Under the Mountain). That jerk branded his name in Thorin’s grandfather’s severed head and cast it out the door as a warning to all Dwarves who dared re-enter Moria.

Azog is another example of a singular Orc trying to throw his weight around as though he’s running some kind of show. Like the Orc-captain who boasted about taking down Barahir and getting his ring. There are others, like the Great Goblin in The Hobbit, whose death so angered his people that they pursued Thorin & Co. for revenge instead of just quietly electing a new leader. I wouldn’t call this loyalty, exactly, but Orcs sure do like to take offense.

Sauron doesn’t seem to care about such petty captains and kingdoms, just as Morgoth was fine with Glaurung living it up as a temporary dragon-king. As long as their presence hinders his enemies, these faraway Orcs are free to do as they please; they still get their mojo from the Dark Lord. Let the Azogs, Gorbags, and Shagrats of the world think their ambitions are their own.

Moving on. Orcish wolfriders and Uruks of Saruman’s command play a large role in the “The Battles of the Fords of Isen”—that is, the events that set the stage for Rohan in The Two Towers, such as the death of the king’s son, Théodred. But aside from their prowess, there is little to be learned about Orcs that we don’t already know. Maybe a few bits of trivia. We see mention of “orcmen,” the Mannish-breed of Orcs that Saruman bred, but still no account of their creation; only that he had them. Not all of Saruman’s troops are the tall Uruk-hai, either. In one battle, Orcs withdraw before the shieldwall of Grimbold (a captain under the Second Marshal) because they “were of less avail in such fighting because of their stature,” requiring taller Dunlendings to take their place. Meanwhile, contrary to popular depictions, the wolfriders seem to be on the smaller side, too. A footnote tells us:

They were very swift and skilled in avoiding ordered men in close array, being used mostly to destroy isolated groups or to hunt down fugitives; but at need they would pass with reckless ferocity through any gaps in companies of horsemen, slashing at the bellies of the horses.

I swear, all the best stuff were little side “author’s notes” from Tolkien. Thank God for Christopher’s comprehensiveness.

Finally, in “The Drúedain” chapter, we learn a great deal more about the ancestors, culture, and perception of the so-called Wild Men of the Drúadan Forest. In the Third Age, they help the Rohirrim reach the Pelennor Fields in time to aid Gondor. But in the First Age, they were an estranged tribe within an estranged tribe of the Edain, the first Elf-friends. What do they have to do with Orcs? Nothing directly, bit we are told that the Orcs are “the only creatures for whom their hatred was implacable.” The Drúedain are misunderstood and mystifying, often considered “unlovely” even to other Men and Elves, yet they are good-hearted and possess a sunny nature that seems to be the antithesis of what it means to be an Orc. For example, while their voices are guttural,

their laughter was a surprise: it was rich and rolling, and set all who heard, Elves or Men, laughing too for its pure merriment untainted by scorn or malice.

In an endnote, we’re told that there are “unfriendly” people who speculate that Morgoth must have bred Orcs from Men (not Elves) such as Drúedain, but even the Elves dismiss it. They say:

the Drúedain must have escaped his Shadow; for their laughter and the laughter of Orcs are as different as is the light of Aman from the darkness of Angband.

In the next installment of this subject, I’ll talk more about that speculation. In the meantime, this Drúedain chapter speaks to superstitions even the servants of Morgoth can possess. Recall The Return of the King and the standing stones that Merry sees, the ones the Riders of Rohan call Púkel-men. Here we learn more about them, particularly in the Elder Days of Beleriand. The Drúedain “showed great talent for carving in wood or stone,” and their stonework included toys, ornaments, or larger effigies:

among the grim jests to which they put their skill was the making of Orc-figures which they set at the borders of the land, shaped as if fleeing from it, shrieking in terror. They also made images of themselves and placed them at the entrances to tracks or at turnings of woodland paths. These they call ‘watch-stones’ of which the most notable were set near the Crossings of Teiglin, each representing a Drúadan, larger than life, squatting heavily upon a dead Orc. These figures served not merely as insults to their enemies; for the Orcs feared them and believed them to be filled with the malice of the Oghor-hai (for so they named the Drúedain), and able to hold communication with them.

Such passages don’t speak much to the society of Orcs, but to the cultures of a world in which they are a staple. For Men, there have always been Orcs. We tend to think of Gondor and the statues of its heroes; they don’t carve their enemies in stone. But the Drúedain do, and they do it with purpose, like setting up gargoyles to scare away evil spirits. But they are playing upon the superstitions of the Orcs, not their own.

The mere existence of such superstitions harbored by the din-horde make the case that Morgoth never pays his own “people” much heed. There’s no education to speak of, no dispelling of myths; Morgoth himself would likely dismiss the Drúedain’s watch-stones as useless if he gave them any thought. You’d think he’d try to clear up the matter for the Orcs, to make them more efficient as his military force. But he doesn’t. He can’t be bothered, and I don’t think Sauron does any differently, after him. Orcs are truly doormats to Dark Lords. Weaponized doormats. Their value is in quantity, not quality. And yet quantity has a quality all its own.

But there are plenty of mentions of Orcs being trained for certain types of battle or terrain, or certain tasks (as we see in tracking vs. fighting). In this chapter alone, we’re told that Orcs who specialized in forest warfare still dared not cross the borders into the domains of the woodsy folk of Haleth. So they can have expertise. But knowledge? Enlightenment of any kind? Screw ’em! Keep them in the dark. Their only purpose is to help Morgoth tear everything down. They oppress the world around them, but Orcs themselves are deeply oppressed. They are bullies by design.

The French statesman (and showrunner of France’s bloody Reign of Terror) Maximilien Robespierre is alleged to have said (translating, of course):

The secret of freedom lies in educating people, whereas the secret of tyranny is in keeping them ignorant.

Whether true or not, it certainly seems like Morgoth would have agreed. He loves the poorly educated! We know Elves and Men and probably Dwarves all have some variety of lore-masters or sages. There are no Orc-sages. Remember, the Orcs serve their master “in fear,” as he is “the maker only of their misery.” He’s not interested in adjusting their beliefs or even in cultivating his own worship, only in fostering their fear. Only in using them before casting them away.

Next time, I’ll talk about the Orc-based theological and moral concerns with which Tolkien struggled—as well as Orcish trash talk—as detailed in the History of Middle-earth books.

Jeff LaSala would like to thank friend and fellow Tolkien nerd Tanya Plashkova for always being there with helpful textual interpretation questions, and of course his brother, John, for his persistent proofreading. Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Macmillan and Tor Books. He sometimes flits about on Twitter.