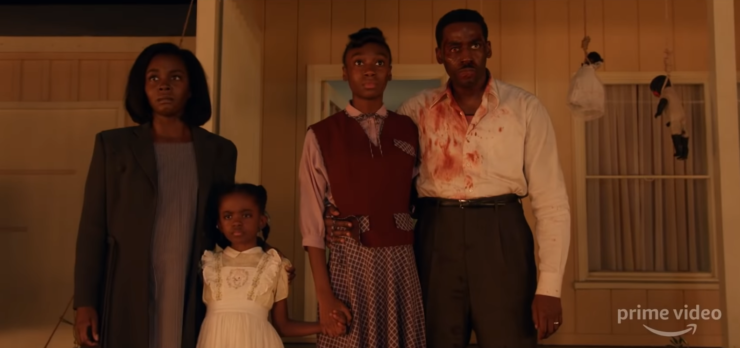

Them, Amazon Prime’s newest horror anthology series, has a lot of potential. The premise—escaping violence in the South, a Black family relocates to East Compton in the 1950s when it was still an all-white enclave and horror ensues—is intriguing. In the wake of other television shows like Watchmen and Lovecraft Country that also took Black history and twisted it with fantastical elements, there was a real opportunity to explore different aspects of racial violence: redlining, white flight, and blockbusting. Unfortunately, Little Marvin, who created Them and wrote four episodes, fails to live up to the potential of his own premise.

The first episode, “Day 1,” opens with a flashback. Lucky (Deborah Ayorinde) is alone with her infant son, Chester, in her house in rural North Carolina. Her husband (Ashley Thomas) and daughters (Shahadi Wright Joseph and Melody Hurd) went to town, leaving them behind. A white woman (Dale Dickey) wanders into the front yard singing “Old Black Joe,” a minstrel song from the 1860s about a Black man waxing nostalgically over a plantation. A gang of white men approach from the distance, and Lucky runs inside only to wake in the car as her husband drives her and her daughters West. It is sometime after the flashback event and, notably, Chester is not in the car. Later, we see Lucky place a wooden box with Chester’s baby blanket and other belongings into a cabinet built into the basement of her new home. The audience does not see what happened to Lucky and Chester until the fifth episode, but it is brutal in the worst way.

Arriving in Los Angeles, the Emorys are enamored with the grand skyscrapers and chaos of big city life, but their thrill melts into terror as the reality of their living situation becomes clear. Henry has purchased a home in the all-white neighborhood of East Compton. The next morning, Betty Wendell (Alison Pill), the queen bee of the neighborhood, gathers her minions for her first attack: blaring “Civilization (Bongo, Bongo, Bongo)” by the Andrews Sisters and Danny Kaye from a dozen radios set up in front of the Emory home. With Henry off getting microaggressed at his new engineering job and Ruby trying to survive high school, Lucky and Gracie suffer the brunt of it. Gracie focuses on reading her favorite book while her mother tries desperately to keep her sanity in check.

That night, the white folks host a get-together to strategize what to do next, but not everyone is as into it as Betty. While the wives trade racist gossip, in the man cave the husbands settle on poisoning Sergeant, the Emorys’ dog. They never get the chance. Gracie wakes in the middle of the night looking for her pup and finds instead a monster in the kitchen.

Buy the Book

The Chosen and the Beautiful

The next morning, Lucky discovers a wound on Gracie’s neck. Henry checks the house, believing one of their neighbors broke in, but the house is sealed. He finds Sergeant dead in the basement, and it pushes Lucky over the edge. Her nerves were barely holding on to begin with, but the threat against her child sets her off. She grabs her gun and runs outside, screaming at the neighbors. Henry drags her back inside before she can get a round off, but the cold war has now escalated into a full on assault.

On a historical note, this may seem like a little thing to be annoyed by, but you simply cannot convince me a Black person would think a racial covenant on a deed in an all-white neighborhood is something so negligible that it’s worth ignoring. Racially restrictive covenants had appeared in title deeds for decades, but got exponentially popular when in 1938 the Federal Housing Authority recommended them as a vital tool for helping real estate agents and developers keep BIPOC out of white neighborhoods. Although the Supreme Court declared racially restrictive covenants unenforceable in 1948 with Shelley v. Kraemer, they continued to be added to deeds of new homes and developments well into the 1950s. Many homes in California suburbs or former white enclaves contain a covenant in their deeds to this day.

That Henry knew the deed had a restrictive covenant meant that he had to know he was moving his family into an all-white community. The first episode implies that he is surprised or disappointed by the neighbors being unwelcoming, but come on. Marvin has said that the Emorys were inspired by Dr. Emory Hestus Holmes, a psychologist and civil rights leader who helped desegregate a white neighborhood in Pacoima, California. In 1960, about five years after moving into the area, he won a civil rights lawsuit filed against his neighbors. Dr. Holmes went in ready to fight segregation and take what he deserved. Marvin did not give the Emorys the dignity of agency. Instead, the first episode frames Henry as unprepared at best, naive at worst. The Emorys aren’t survivors or fighters but victims.

Tens of thousands of Black Americans relocated to California in the 1930s and 1940s (140,000 to Los Angeles County in the 1940s alone), with many headed to the shipyards during World War II. Henry would have known which neighborhoods were redlined because not only would other Great Migration participants sent word back home but he also would’ve encountered resistance from white real estate agents when trying to buy outside that. Henry chose to put his family in a risky position even after what happened at their old home and he chose to do so without telling his family ahead of time; Lucky had every reason to be mad at him.

When the trailer first dropped, the shots of golliwogs and blackface minstrelsy were as off-putting as they were meant to be. However, the premise was enough to convince me to give the show a try. Initially I pitched this as a review of the full season, but by the time I finished the first episode I knew I could not watch any more of it. Really, I suspected I would not continue after I heard about what is done to baby Chester in episode five, but as I said, I wanted to see if it was good enough to power through. It was not. I did not enjoy the first episode at all. I expected scares and social commentary, but what I got was a crushing wave of cruelty with no reprieve or retribution in sight.

To be fair, the episode as a whole is not objectively bad. The actors all outshine the script. Ayorinde and Thomas have strong chemistry together, and Joseph and Hurd handle difficult scenes with ease. Pill somehow pulls off a character who is equal parts Mean Girl, Stepford Wife, and WKKK. Dickey only appears briefly, but she brings her best and is always enhances whatever she is in. The set and costume design are impressive and make good use of the prestige streaming budget. Checco Varese’s cinematography is visceral and gorgeous. And, as I said earlier, Marvin’s premise is compelling. But the episode is unrelentingly intense. The violence, whether explicit or implicit, is so pervasive that it smothers everything around it. By the end of the first episode, the only thing I know about the characters is how the Emorys respond to racial trauma and the white people’s varying degrees of racist. No one has any personality beyond oppressor or oppressed.

In “Day 1,” most of the horror is contained to looming dread. Chester’s absence, Sergeant barking at seemingly nothing, the dark basement. It is unclear by the end of the first episode what the supernatural entity is, whether it’s connected to the woman from the flashback, the house, or something else haunting the Emorys. Having read detailed recaps of what happens in the rest of the season and what the supernatural horror really is makes me even less inclined to go back and finish it.

In stories like Get Out, the horror is rooted in the experience of being Black in America and the racism and oppression we must navigate. In Them, however, the horror comes from the racial violence that is inflicted upon our bodies. What the white neighbors do to the Emorys may be inspired by real events, but I need more from a show than just replicating racism. The racism and violence rarely feels like anything more than brutality for brutality’s sake. Whether or not it crosses into “trauma porn” territory is up for debate, but regardless, Them was a swing and a miss for me.

Alex Brown is a librarian by day, historian by night, author and writer by passion, and a queer Black person all the time. Keep up with them on Twitter, Instagram, and their blog.