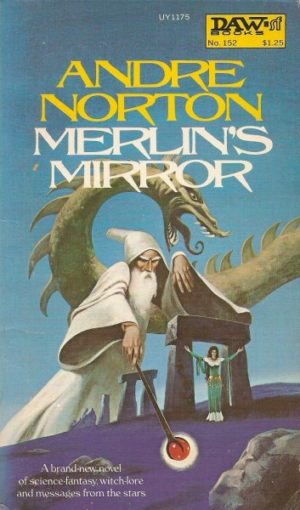

Andre Norton was a master of the adventure plot, and she loved to mash up genres—science fantasy was one of her favorite things, as the Witch World cycle demonstrates. Every so often however, she either did not connect with her material, or the book she wanted to write simply did not fit into her wheelhouse. Merlin’s Mirror is one of these rather rare misfires.

The idea is not terrible. It’s the Witch World concept: a vanishing Old Race of impossible antiquity, an alien world of war and superstition, ongoing attempts to bring peace and higher civilization to the reluctant natives. The Arthurian canon is, in a lot of ways, about this. Adding basically Forerunners to the mix, and applying Clarke’s Third Law to the technology, could work.

Here, unfortunately, it doesn’t. She throws together one of her standard mixes: the underground Forerunner installation with its interstellar beacon, the stasis pod with its healing liquid, the hybrid offspring of a human woman and an alien power, the inescapable geas or foreordained destiny, the magical weapon that’s really extremely advanced technology, the evil opponent who thwarts the protagonist at every turn. It’s worked for her before and will again, but in this case it collides with a plot structure that’s even more confining than Norton’s usual pattern of deterministic dualism.

When it’s Norton doing the determining, the characters have no choice to but to do what the plot tells them to. But the Arthurian saga has its own set of plot points, and she just can’t seem to fit herself into them.

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

Myrddin, the boy without a father, is the product of artificial insemination triggered by the last failing remnant of a nearly extinct alien race. He is a literal and figurative device. He has no agency and no possibility of achieving any. He exists solely to do two things: repair the beacon and engineer a physical body for an ancient ruler who will bring peace to this war-ravaged world.

In this way she explains the exploit of the Giants’ Dance, bringing the king-stone of Stonehenge over the water. There’s a lot of buildup about how important this is and how hard it is for the strange boy to get backup from the local ruler to go and fetch the stone from the Continent, but then it’s no big deal and we never even see him bring it back. He zips from floating it out of the earth using the alien sword he found in a grave in Stonehenge, to installing it, and then off to the next episode in the pre-baked saga.

Same thing happens with the exploit of Vortigern (or here Vortigen)’s tower that keeps falling down. He’s captured and dragged off as a sacrifice to the demons that curse the tower, but talks fast and convinces the king that it’s not really demons, it’s dragons symbolic of old Britain and the new Saxon invasion. Then he pulls an illusion, along with a piece of engineering knowledge about the land the tower is supposed to be built on. And that’s it for that, with some side issues about how people think he’s a demon.

And there’s Nimue, who is also an alien hybrid, but she’s Evil. He runs into her every time he tries to get anything done. She doesn’t stop him from getting the king stone or proving why the tower keeps falling down. She saves her big effect for Merlin’s major task: bringing back to life the ancient ruler whose name is Arthur.

Nimue is the distillation of all the misogyny that’s inherent in the Arthurian canon. Whereas other modern writers have recast and revamped the women of the canon, Norton doubles down. All the women are either sluts (her actual word), pregnant and submissive, vessels for alien sperm, actively evil, and/or dead. The Old Race is alien; it can’t breed with humans except through science (though there are other human hybrids, so, plothole?). Myrddin is only attracted to his own kind, and that’s Nimue—but he’s supposed to be a sexless device without attachments, and anyway she’s Evil.

He manages to escape her traps and facilitate the insemination of the Duchess of Cornwall, which involves convincing the thoroughly human King Uther that he’s being magically united with this week’s lust object while her husband is off fighting, while also convincing the Duchess that her husband has come back for a night of wedded bliss, but it’s really just a dream and the real “father” of Arthur is, basically, a drone with alien sperm on board. But once that’s done and he’s also done the part of the job where he has to convey the result of the breeding to another descendant of the Old Race, Ector, for fostering, he walks straight back to his hidden cave and lets himself be imprisoned there for sixteen years.

Which makes no sense at all, because he’s supposed to be educating Arthur while Ector raises him. But the text says Nimue imprisons him in an oak tree or a crystal cave or whatever—in this case, an ancient installation that includes the mirror which has educated him and is supposed to educate Arthur in turn—so into the stasis box he goes, and that’s why the whole Arthur experiment fails, but he doesn’t do anything to stop it. Because that’s what the text says.

By the time he comes out, he manages to shut off Nimue’s main access to power—nice adventure bit there, lots of hair-raising escapes and some classic Norton quest-plot—but Nimue has already made sure Morgause, Uther’s slutty daughter, has seduced her supposed (but not really) brother Arthur, and there’s the original story of Modred, who will bring down the once and future king. Arthur is a total stranger to the man who now calls himself Merlin, and he looks like Uther instead of a dark-haired, dark-eyed, pointy-chinned member of the Old Race like Merlin (or the Witches of Estcarp for that matter). He’s been educated as best Ector knew how, but not in the way he was supposed to be. He’s not at all the soulmate Merlin had hoped for.

And so the grand experiment trails off into betrayal and disappointment. The beacon is doing its thing but the Star Men never show up. Arthur and Modred fight to the death, and Arthur is mortally wounded, but there’s that stasis box, which Merlin manages to get him to, and there he stays, until the Star Men finally come back. If they do. And Merlin sleeps there, too. Until whenever.

In the hands of a writer who could manage complex characters, this might have been a much better book. There are brief, poignant flashes: Merlin’s utter aloneness and loneliness, his deep shock on meeting Arthur and finding him nothing like what he had expected, and Nimue’s speech at the end about the stark dualism he’s been indoctrinated with, which may not be the truth, or the right thing, at all.

The same applies to the structure of the plot. If Norton had been fully at ease with the shape of the story, she might have been able to weave the individual episodes into a coherent whole. She would have known when and how to flesh out each of them, and the blocks and reversals would have made more sense.

It doesn’t help that “my” modern Merlin is Mary Stewart’s, and Stewart did fit herself into the framework and make it her own. Norton struggles with the story she wants to tell versus the story that’s already told. The elements end up fighting against one another.

I would have been happier if she had given up on the Arthurian saga, let it be the backstory, and written the other end of it: the return of the Star Men and the revival of Arthur and Merlin. That might have been more within the range of her talents and inclinations. It’s too bad she didn’t go there. But then again, she wrote so many other, similar stories that did work; and Mary Stewart’s Merlin is still and always there for me.

Because I’ve got the books right here, and because you’ve asked, I’ll read Flight in Yiktor next, and its sequel after that.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.