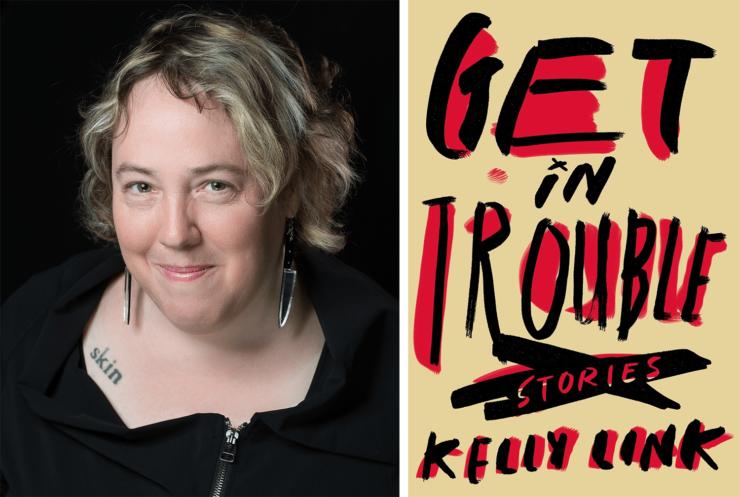

The Tor Dot Com Socially Distant Read Along is walking between a pair of apple trees and following a winding path through Kelly Link’s latest short story collection, Get in Trouble! Each Wednesday at 2PM EST we’re discussing a new story. Last week’s was “The Summer People”, and because I had a lot more to say after my time on Twitter was up, I figured I’d take a closer look at the way Link explores class and modernity via what is, at heart, a fairy tale.

“The Summer People” begins in a culture clash, very similar to the one in Shirley Jackson’s “Summer People”. In Jackson’s story, an older couple, the Allisons, have spent a few months at their summer house, and decide to stay past Labor Day. We get the sense immediately that the couple is decently middle class, maybe a little above. They have an apartment in the City (when Mrs. Allison speaks to the local grocer it’s “as though it were [his] dream to go there”) and a small modest home on a lake in New England. The story is set at a time in U.S. history when it wasn’t completely unheard of for a middle class couple to afford this, so it isn’t like now, where if a person has an apartment in Manhattan and a summer place they’re probably either fully rich, or at least from a wealthy enough family that they were able to inherit property. However, that still creates a significant gap between the Allisons and the townsfolk, if not financial, exactly, at least in their outlook on life. The Allisons’ only experience the small lake town as a vacation place, a place of recreation and escape. They have no stake in the land or the culture. It isn’t their real life, they treat it like a diorama before going back to “real” life in the city, and my sense has always been that that’s what they’re being punished for. If they participated in the community, they might have been welcomed to stay.

Link complicates this story and brings it into the modern era. Ophelia’s family is wealthy, and used to use Robbinsville as their “summer place”. But they already lived in the South, in Lynchburg, a place I suspect the Allisons wouldn’t even consider a “real” city. They’ve probably retreated to Robbinsville because of a scandal, but even if that’s the case they’ve been able to move fluidly from one wealthy social circle to another. We learn that they’re friends with the Robertses (one of the families that employs Fran and her father as caretakers) and that Ophelia has her own Lexus. But another interesting complication is that Ophelia isn’t a rich, popular mean girl—she’s an outcast because of the rumors that she’s queer. When she talks to Fran it’s about TV shows she watches, a knitting project, and the party on Saturday that neither of them are going to attend. Fran is a fringe member of the community, but Ophelia is fully an outcast—whether it’s because Fran = weird and Ophelia = queer, or whether their class status is part of that, is left ambiguous.

Fran and her father are a very specific type of Southern Rural Poor, and bounce between a few of the class markers that come with that. The house they live in was ordered from a Sears Catalogue, which for a long time was the major link between the rural South and the rest of the world. Her dad makes moonshine, which was a major source of DIY, non-taxed income in the rural South, just like weed is today. (It’s also how we got NASCAR!) When he feels guilty about making moonshine, he goes to tent revivals to get saved for a while. Again, there’s an utterly realist version of this story, but Link chooses to crash her rural South into modernity, and then tangles it all up with magic. goes in for a couple of twists. The Sears Catalogue house is mirrored in the magical fairy house the summer people live in; the moonshine is laced with a magical honey the summer people produce, and Daddy finds his tent revivals on the internet. When Fran is deathly ill with flu, but can’t afford the bill at “the emergency”, she Fran plucks out three strands of her hair and sends Ophelia on a quest to get an elixir from the summer people.

Link’s dedication to layering class issues into the story carries through in the language, which is slangy and Southern, but also self-aware. Fran uses phrases like “hold up”, “give here”, “ain’t”, “reckon”, and my personal favorite, “teetotally”. But when Ophelia says “hollers” Link is sure to tell us “Fran could hear the invisible brackets around the word.” It’s a delicate moment: Ophelia may be Southern, but she’s not the kind of Southern that would refer to a valley as a “holler”, and her accent wouldn’t turn the word that way, even if she did. Ophelia chatters to Fran about going to college in California, blithely assuming that since Fran is smarter than her, she’ll be making college plans, too; in another moment, Fran tells Ophelia that their washroom is an outhouse to underline her assumptions about Ophelia’s assumptions about her, while also sidestepping her embarrassment at the state of her house.

Once Ophelia learns the truth of the other summer people, she makes the connection between the rich tourists and the faeries explicit, telling Fran: “Like how we used to come and go,” Ophelia said. “That’s how you used to think of me. Like that. Now I live here.” But Fran, for the first time in the story, drops her armor: “You can still go away, though,” Fran said, not caring how she sounded. “I can’t. It’s part of the bargain. Whoever takes care of them has to stay here. You can’t leave. They don’t let you.” Fran is bound to the summer people in a mirror of the poverty that would almost certainly bind her to some version of the life she lives in her hometown. It’s impossible to save enough money for college, or a good car, or a home, or even a move to a new apartment in Asheville, if you’re living check-to-check in a tiny town in North Carolina. There’s no way to get ahead.

Link grounds us again a few pages later. Ophelia receives a magical gift, a token of the summer people’s favor. But rather than a vial of healing elixir, or lamp that grants wishes, or a spyglass that shows the future—it’s an iPod case.

The iPod was heavier now. It had a little walnut case instead of pink silicone, and there was a figure inlaid in ebony and gilt.

“A dragonfly,” Ophelia said.

“A snake doctor,” Fran said. “That’s what my daddy calls them.”

“They did this for me?”

“They’d embellish a bedazzled jean jacket if you left it there,” Fran said. “No lie. They can’t stand to leave a thing alone.”

“Cool,” Ophelia said.

Since the summer people seem to have accepted Ophelia, Fran takes her to spend a night in the bedroom that will show you your heart’s desire while you sleep. The room is “all shades of orange and rust and gold and pink and tangerine”—but then the next sentence brings us back down to Earth when we learn that the room’s decor is made from repurposed T-shirts that Fran’s mom bought from thrift shops all over the state. And to twist the reality knife a little more: “I always thought it was like being stuck inside a bottle of orange Nehi,” Fran said. “But in a good way.”

In the end, Ophelia is trapped in a grimmer version of the fairy tale she thinks she wants, and she gets to leave her status as a summer tourist behind, as tied down to Robbinsville as Fran ever was, her life as compromised by a single fateful decision as the Allisons’ lives were. Fran has escaped—was that her heart’s desire all along?—but it’s telling to me that even in her new life, thousands of miles from home in Paris, she’s still poor, living in a squat, carrying her past with her everywhere she goes.

We’ll be discussing the next story in the collection, “I Can See Right Through You” later today—Wednesday, October 14th—at 2PM EST. Join us on Twitter at #TorDotReads!