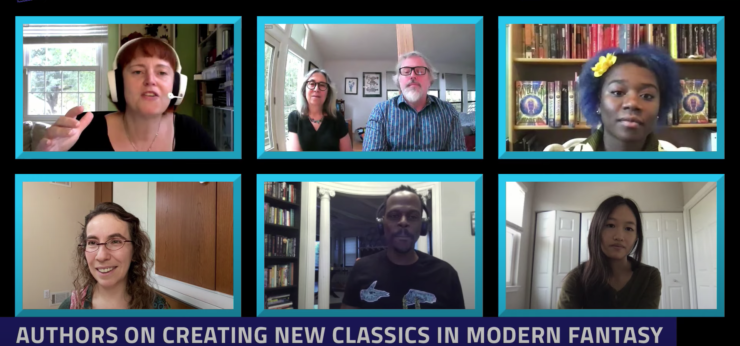

Over the weekend, New York Comic Con brought together a great panel of fantasy authors to discuss how modern fantasy builds off of the works that came before, and how they’re building a new future for the genre.

Check out the discussion, which includes P. Djeli Clark (Ring Shout), Jordan Ifueko (Raybearer), R.F. Kuang (The Burning God), Naomi Novik (A Deadly Education) and Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (A Peculiar Peril, The Big Book of Modern Fantasy). Petra Mayer, the editor of NPR books, moderated the panel.

What are the traditions of fantasy, and how do your works interact with them?

- Novik: “Tolkien is probably one of the people you’d mention, not necessarily starting fantasy, but creating the fantasy genre in the bookstore. Which is not the same thing as creating fantasy in terms of writing…There’s a long stretch when I was a young reader where everything stood in relation to Tolkien. Possibly you have something similar to Harry Potter — a huge mainstream thing that dominates people who aren’t into fantasy’s perception of fantasy.”

- Ifueko: “When I think of traditions, I think of what fantasy has traditionally done. Interestingly, in both Eurocentric and Afrocentric fantasy traditions, the stories that involved the fantastical usually served to reinforce the greatness of what was in place in that culture. With Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, you have a lot of stories about a rightful ruler being brought back or justified — the old guard system has been restored and everything is back to normal.”

- Clark: “Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were my formative reads… nearly all of them were restorative. For a long time, I thought that’s what fantasy had to be: you had to have requisite dark lords, somebody fighting for the throne, and you needed a whole bunch of bad guys that you could kill really easily. As Jordan says, I always know it needs to be more complicated, because I know more. It’s like that innocence has been lost. I think that we do see that in a lot of fantasy today. There’s a lot of calls to deconstruct, or simply complicate and subvert, even in the fantasy that we see in movies.”

- Ann VanderMeer: “One of the things I noticed a lot with classic fantasy was that many of the stories and early fairy tales were all morality tales. So it is about maintaining that status quo. When I look at the stories in modern fantasy, they’re more urbanized in a sense where people are dealing with social messages in their stories as opposed to trying to get back to a status quo. It’s trying to reimagine what the world can be, if things are different an a bit fantastical.”

- Jeff VanderMeer: “I like to take strains that are not the dominant ones — my Ambergris series is really influenced by decadent-era writers — I think that there are other traditions that you can profitably use as a starting point, to create something new, that’s either a renovation or an innovation, and I think that’s what a lot of writers are doing now. And, also bringing a lot of different traditions in that weren’t considered part of mainstream fantasy which was obviously very white for a long time.”

- Kuang: “The structure of the story is the golden days in the shire or the wonderful first year at Hogwarts that gets disrupted by an evil outside force and the whole goal of the main story arc is to return things to how they were at the beginning without any critical examination that the households [have] slaves, etc. I think that the first book that introduced me to arcs that disrupted and interrogated the status quo was N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, whose entire foundation is what if the entire world is broken and deserves to be destroyed. Imagining alternative better futures that require wrecking everything around us is a strain that I really enjoy reading in modern fantasy.”

Where’s the dividing line: what makes modern fantasy modern for you?

- Ifueko: “I think that we live in a world that’s more globalized than it’s ever been. It becomes harder to categorize what our authentic voices are, because I think fantasy is where all those different influences are given freest rein to exist. For me, someone who grew up with Anansi the Spider and other West African mythologies and fantasies, and also with a house full of Shakespeare and Jane Austin — because Nigeria was a British colony, so that was my parent’s formal education — and growing up on Nickelodeon and Disney, an authentic voice isn’t something that can be packed up neatly in ‘she writes West African fantasy.'”

- Clark: “My own introduction into fantasy was Tolkien, and when I first started to imagine fantasy outside of those Eurocentric lenses, in the beginning, I wanted to make them an African version. In some ways, I think there’s room to talk about that in the lens of modern fantasy because what you had for the first time was people of color and of African decent creating fantasy often based on those old models, but telling new stories, not simply culturally, but also from their own social and political backgrounds.”

- Novik: “I wonder if part of it isn’t the ways in which we are more widely connected, and the ways in which we’re each. When you think about an ordinary person, it was already possible to have relationships and connections with people at far greater removes from me, and I think that that’s a phenomenon of our connected age, that I think is clearly having some sort of influence, hopefully broadening the narrative because it means you’re getting more influences, more connections from outside.”

- Ann VanderMeer: “There’s the influence of pop culture. A lot of young people come to fantasy through other things besides books, they might come to it from tv or movies, or video games. The modern fantasy writer and reader have influences beyond just the written word.”

- Jeff VanderMeer: “If you want to look at ‘North American Fantasy’ — the rise of the professional magazine market after World War II is really where we chart that beginning, and why we cut it off 10 years from the present is because we feel that is a different era, and also we need the perspective of time. The way I see it is that there’s this modern fantasy period from WWII, and suddenly there’s this amazing, complete blowing up by the genre — there’s all these new perspectives coming in, whether they’re using traditional structures, or new structures, so I see it as we’re in the second period of modern fantasy right now.”