In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week’s installment is the third in a short series on that most infamous of Noldorin Elves: Fëanor, father of seven sons and creator of the Silmarils. Next time, we’ll look at Fëanor’s Oath and the turmoil it inspires.

The last two installments of this series on Fëanor explored the Elf himself and his close personal relationships. We saw that his relationships with others were marked by selfishness and pride: he only kept close those who were useful to him, but in time, he pushed even these away. He listened to no one’s advice or counsel after finally rejecting Nerdanel, abandoned his father after the loss of Míriel, and estranged his other kinsmen by becoming secretive and covetous. As a craftsman he was superbly talented, and he was greater than any other of the Noldor apart from Galadriel. But his selfishness and arrogance only grew after he created the Silmarils: he hoarded their light from all eyes save those of his father and sons, and began to forget that in making the jewels, he used materials that were created by someone else. He began to claim Light as his own. Last time, we concluded with the observation that Fëanor followed nearly step-for-step in Morgoth’s pattern even as he became the Enemy’s most outspoken critic. He fell prey to the seduction of Morgoth’s lies, internalizing them, becoming their mouthpiece…

Fëanor’s blindness to his own faults is one of his greatest failings, one prompted by arrogance and overweening self-confidence. There is no humility in Fëanor’s character, no gentleness, and certainly no respect for the cares and joys of those around him. Even his love for his father is selfish; his love for his sons, if such it can be called, is simply manipulative.

Let’s pick up the story now with Fëanor’s troubled relationship with his half-brothers, Fingolfin and Finarfin. Fëanor was never pleased with his father’s second marriage, and “had no great love for Indis, nor for […] her sons. He lived apart from them” (Sil 56). It was said by many that the breach which divided the house of Finwë was unfortunate, and had it not occurred, Fëanor’s actions might have been different, and thus the fate of the Noldor might have been less dark than it eventually was (57).

But that was not to be. Morgoth (still called Melkor, at this point), after being imprisoned in the Halls of Mandos for three Ages and suing for pardon, began to spread rumors and dark whisperings among the Noldor, and “ere the Valar were aware, the peace of Valinor was poisoned” (Sil 60). Over time, Finarfin and Fingolfin grew jealous of Fëanor’s power and glory, and of the awe their elder brother inspired when he wore the great jewels flaming at his brow during feasts in Valinor. So Melkor watched, and began to spread lies. To Fëanor it was told that Fingolfin and his sons were planning to usurp him, while Fingolfin and Finarfin were informed that Fëanor was planning to expel them from Túna now that he had their father on his side.

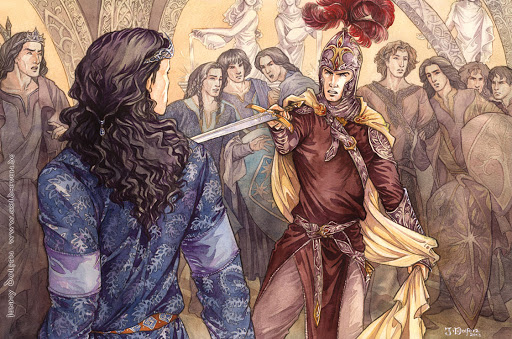

And each believed the lies they were told. The Noldor began to forge weapons by the instruction of Morgoth; Fëanor, intrigued, did so in a secret forge, producing “fell swords for himself and for his sons, and made tall helms with plumes of red” (Sil 61). Then amidst the growing strife Fingolfin went to Finwë and begged his father to intercede, restraining Fëanor and putting an end to his public speeches against the Valar. But as he did so, Fëanor entered—brandishing his sword at Fingolfin, he ordered him to leave with violent and cruel words.

The Valar, believing the discontent originated with Fëanor, summon him to the Ring of Doom, where it was finally revealed the Melkor (soon to be Morgoth) was at the root of the shadows and discontent spreading in Valinor. But Fëanor “had broken the peace of Valinor and drawn his sword upon his kinsman” (Sil 62), and so Mandos banished him from Tirion for twelve years. Fëanor took his seven sons with him into exile, and Finwë, out of love for his first son, followed them. Fingolfin took up rule of the Noldor in Tirion. Neither Indis nor Nerdanel joined their husbands in exile, but rather took up residence together—likely, if I may be allowed the speculation, glad to no longer be placating the selfish, even greedy demands of their respective spouses.

Buy the Book

The Empress of Salt and Fortune

Then Melkor, seeking to take advantage of Fëanor’s humiliation before the Valar, came to Fëanor’s stronghold at Formenos and sought to treat with him. But he overreached and spoke of the Silmarils, and instantly Fëanor was aware of his hidden designs. Fëanor cursed Melkor and sent him away; but Finwë sent messengers to Manwë.

At this point, we can see the extent to which the action is driven by the pride and greed of the various characters. In reality the lies and manipulations of Morgoth, though they obviously bring the trouble to a head, do no more than exploit the negative thoughts, feelings, and tensions already in existence. Indeed, this seems to be how the Enemy accomplishes his most successful work: stoking the glowing embers of hate, jealousy, and greed until they burst into flame. The strategy certainly works in this case. Though we can’t absolve Finwë and Fingolfin and Finarfin for their misdeeds, Fëanor in particular is driven by his own insatiable desires. He seizes any chance to attack those around him whose motivations do not fall in line with his own, and instead of cultivating a healthy sense of remorse or repentance when he is confronted, he simply becomes bitter and angry. As we read before in The Peoples of Middle-earth, “opposition to his will he met not with the quiet steadfastness of his mother but with fierce resentment” (333).

As Fëanor stewed in his own bitterness, Melkor was busy on projects of his own—specifically, recruiting the monstrous Ungoliant for his evil designs. Heedless and unthinking, he promises her “whatsoever [her] lust may demand” freely and openly (Sil 66). Ungoliant at last agrees to the proposition, and during a festival time in Valinor they arrived in Valmar and saw the Light of the Two Trees, Telperion and Laurelin.

Now, Fëanor was at the feast, not by desire, but because he alone was ordered by Manwë to attend, for the reconciliation of the house of Finwë. Even as Fëanor and Fingolfin joined hands before Manwë and swore their peace—in word if not in their hearts—Ungoliant and Morgoth struck the Trees to their deaths, and Ungoliant drank the Light, spewing forth her poison into the hearts of the Trees. Then Morgoth and his lackey hastened away to Formenos, where Finwë had remained in protest of what he perceived as the injustice of the Valar. Then Finwë, first of all the Eldar, was slain, and Formenos ransacked, and the Silmarils, the Jewels, the pride of Fëanor, were stolen, though they burned the hands of Morgoth with an unbearable pain as he bore them away.

Back in Valmar, Yavanna attempted to heal the Trees, to no avail. Fëanor is then called upon to relinquish the Silmarils, to offer them up for the healing of Valinor and the restoration of Light. This is Fëanor’s great test. In the previous essay, we explored the significance of Fëanor’s artistry. I pointed out that this moment refigures the moment in which Aulë is faced with a similar decision: either he must reject the greater good (in Aulë’s case, the plan of Ilúvatar), or see his greatest creations (the Dwarves) destroyed before his eyes, or even be called to do the deed himself. Fëanor, understandably, falters. He stands in silence. It’s easy to imagine the fear and despair tugging at his heart in the moment. The Valar push him to answer, but Aulë steps in: “Be not hasty!” he insists. “We ask a greater thing than thou knowest. Let him have peace yet awhile” (Sil 69).

Silence stretches long in the palpable darkness. The fate of Arda hangs in the balance.

Then Fëanor speaks, and his words are full of grief and bitterness:

For the less even as for the greater there is some deed that he may accomplish but once only; and in that deed his heart shall rest. It may be that I can unlock my jewels, but never again shall I make their like; and if I break them, I shall break my heart, and I shall be slain; first of all the Eldar in Aman. (Sil 69)

After long brooding, he reaches his decision: “Then he cried aloud: ‘This thing I will not do of free will. But if the Valar will constrain me, then shall I know indeed that Melkor is of their kindred’” (70).

In the darkness and silence that follows, messengers arrive from Formenos. These messengers are unnamed in The Silmarillion, but in an expanded version of the story in Morgoth’s Ring, we’re told that they were led by Maedhros, Fëanor’s eldest son (293). They come before Manwë and, unaware that Fëanor is present, Maedhros relays the disastrous news: Melkor has come to Formenos, slain Finwë, and taken the Silmarils. Fëanor “[falls] on his face and lay[s] as one dead, until the full tale [is] told” (MR 293). Then, according to The Silmarillion, he rose—

and lifting up his hand before Manwë he cursed Melkor, naming him Morgoth, the Black Foe of the World; and by that name only was he known to the Eldar ever after. And he cursed also the summons of Manwë and the hour in which he came to Taniquetil, thinking in the madness of his rage and grief that had he been at Formenos his strength would have availed more than to be slain also, as Melkor had purposed. Then Fëanor ran from the Ring of Doom, and fled into the night; for his father was dearer to him than the Light of Valinor or the peerless works of his hands; and who among sons, of Elves or of Men, have held their fathers of greater worth? (70)

Fëanor’s sons follow him anxiously, fearing that in his great grief he might slay himself (MR 295). Now, the narrator reveals, “the doom of the Noldor drew near” (Sil 70).

But the narrator also points out that “the Silmarils had passed away, and all one it may seem whether Fëanor had said yea or nay to Yavanna; yet had he said yea at the first, before the tidings came from Formenos, it may be that his after deeds would have been other than they were” (70).

Again, we see that Fëanor’s story is full of might-have-beens: if Míriel hadn’t been so tired and refused to return to life; if Finwë had been content with Fëanor instead of remarrying; if the brothers hadn’t believed Melkor’s lies—how different things might have turned out! But this particular might-have-been is, I think, the most interesting: things might have been very different, if only Fëanor had said “yes” to Yavanna. Never mind that Morgoth already had the Jewels. Never mind that his acquiescence couldn’t have changed anything anyway. If he had just said “yes,” then “it may be that his after deeds would have been other than they were.”

The claim is vague, but luckily, an earlier draft might just clarify what Tolkien was thinking when he penned these lines. That version reads, “Yet, had he said yea at the first, and so cleansed his heart ere the dreadful tidings came, his after-deeds would have been other than they proved” (MR 295). Now, this claim is more confident: his deeds would have been different. Clearly, Tolkien was less sure about that in the later draft. But that other phrase—“and so cleansed his heart”—is useful and, I think, instructive.

Agreeing to give up the Silmarils would have been painful, perhaps a lasting grief, but it would have illustrated that Fëanor could let go: that he didn’t have to cling to his possessions and to those he loved with a death-grip. Relinquishing the Silmarils for the betterment of others (and himself!) would have meant that Fëanor was able to set aside his greed and possessiveness long enough to recognize that the Jewels weren’t truly his anyway—he didn’t create the holy Light he imprisoned within them.

Soon afterwards, Fëanor actually accuses the Valar of hoarding the Light, of intentionally keeping it away from Middle-earth. “Here once was light,” he announces, “that the Valar begrudged to Middle-earth, but now dark levels all” (Sil 73). What he doesn’t seem to recognize is that he’s doing the exact same thing. Again, his inability to see past his own desires or to recognize his faults is his downfall: only this time, it affects the fate of the world.

In a different draft in Morgoth’s Ring, the blatant irony of Fëanor’s choice is even more pronounced. As he speaks to the Noldor, he twists himself in lies and bitterness until he can’t even recognize the fact that he’s playing directly into Morgoth’s hands. “Feanor was a master of words, and his tongue had great power over hearts when he would use it,” the narrator explains:

Now he was on fire, and that night he made a speech before the Noldor which they have ever remembered. Fierce and fell were his words, and filled with anger and pride; and they moved the people to madness like the fumes of hot wine. His wrath and his hate were most given to Morgoth, and yet well nigh all that he said came from the very lies of Morgoth himself. (111)

Fëanor urges the people to rebellion and self-imposed exile, and he declares that “when we have conquered and have regained the Silmarils that [Morgoth] stole, then behold! we, we alone, shall be the lords of the unsullied Light, and masters of the bliss and the beauty of Arda! No other race shall oust us!” (112).

These words are at the heart of the more subtle speeches in the drafts that followed: Fëanor imagines, once again, mastery over others, tyranny, and a narrative of racial supremacy that, though it’s less explicit elsewhere, the Elves are never quite able to let go.

But could things have been different? Had he said yes, would his heart actually have been cleansed? On one level, it’s like the narrator says: a moot point. He didn’t say yes, so we’ll never know. All the same, it’s important to point out that Tolkien leaves that option open. Despite all of Fëanor’s failings, despite all his misdeeds, the wrongs he has done and will do, Tolkien reminds us: there might have been hope. After all that, Fëanor might have been saved by making a different, seemingly inconsequential choice.

So, although Fëanor is at this point lost in a morass of evil, and though he soon swears a vow that operates as the force behind many of Middle-earth’s disasters, there is still a message of hope here. In the midst of one of the most depressing stories Tolkien ever wrote, a small light shines. Don’t ever say there isn’t hope. Don’t give up. The courses of our lives aren’t immovably set, and the choices we make matter in the grand scheme of things. Indeed, though all is dark now, we’ll see that Fëanor’s story ultimately ends in redemption, ends in a glorious act of generosity and humility that ultimately makes possible the resurrection of the world into perfection and healing.

Megan N. Fontenot is a Tolkien scholar and fan who’s happy to have a way to share Tolkien with fellow fans even when the world seems to be falling to pieces, and even happier to find a glimmer of hope even in a dark tale. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 and feel free to request a favorite character while you’re there!