K.M. Szpara’s debut science fiction novel Docile is already being compared to other seminal works in genre on sexual violence, including Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. The comparison is legitimate; like Atwood, the danger in Docile is too real. Szpara has taken the danger of the world we live in and used it to construct the world as it might be.

Content warning: discussions of sexual violence.

Elisha Wilder was born into a family kept in a permanent underclass by debt, which is accumulated and inherited without end in a dystopia even deeper than our own. Elisha’s mother took on the work of a Docile: a bondservant who sells the use of their body for years of their life in exchange for the forgiveness of some debt. She used a designer drug called Dociline, a dissociative that allows the user to be somewhat absent from events while their body is still present. However, this damages Elisha’s mother permanently; she loses her personality and will even when she no longer uses the drug.

Seeing no other way out of penury, Elisha presents himself to the Docile market on his twenty-first birthday. He comes up with a plan: to sell the remainder of his life and all his free will in exchange for his family to be debt-free. This allots them no income nor privilege. It just gets them to zero. That’s the deal, and someone accepts it.

Naturally, Elisha’s buyer is Alexander Bishop III, scion of the billionaire family that owns the patent on Dociline, the drug that keeps slaves biddable and not-quite-conscious. Armed with the bare rights to personhood which owned individuals retain, Elisha refuses the benefits of this drug. Remembering what it did to his mother, he would rather bear the torture of this life than forfeit his consciousness to it.

This choice puts Elisha in a bizarre position through the events of the story. His buyer must contend with him as a person, despite an inhumane contract. Elisha is fully conscious as he experiences the cruelties and excesses of the upper class of his society, and he must suffer excruciating use of his physical and emotional energy as intrigue around the status of Dociles swirls around him. He must decide whether he will be an instrument of his own liberation and the freedom of people like him, thereby destroying the person he cares for most and the social order he has lived in all his life.

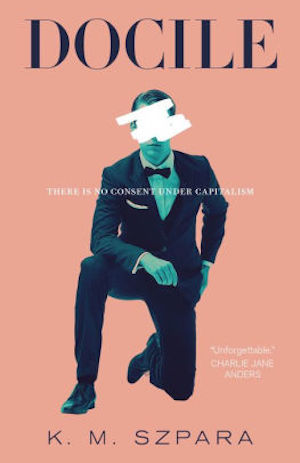

Buy the Book

Docile

Told in alternating perspectives between Elisha and Alex, the story is a seductive yet difficult one wherein Elisha must survive and Alex must begin to see Elisha as something more than a “cocksucking robot.” Sex acts are central and they are not clothed in metaphor or florid language. Content warnings abound for sexual assault, all kinds of abuse, and graphic descriptions of sex and violence. Cum is mopped off faces and floors, swallowed, and never sublimated. Docile is not for the faint of heart. No story that dwells in the question of personhood can be.

It is that central conflict which brings the personal into the political and turns the story of one young man into a revolution. It is that same conflict that caused me to look at Docile not just as a work of fiction, but as a turning for genre fiction as a whole. Readers will look back at books like Docile and say “here is where the change began.”

Let me explain.

By the time I became an adult, I had read more instances of rape and coerced sex than I had of mutually pleasurable and equitable sexual contact.

The count wasn’t even close; the science fiction, fantasy, and horror books that raised me and substituted for both parents and sexual education teachers often relied on rape and sexual assault to tell stories about heroism, innocence, and power to a degree that suggested there was no other way to tell those tales. Ironically, I was separated by a beaded curtain and stern warnings from any content that showed two or more adults engaging in fully-informed and consenting sex acts. But books about dragons and Star Trek and ghosts served rape and attempted rape with predictable regularity to an audience that was hardly warned at all.

Here is the backwards bargain: we are asked for our consent when our media wants to show us a loving embrace. We have assault thrust upon us under the dubious auspices of a PG-13 rating, if that.

If you think about your own experiences, I am willing to bet they are similar.

Reading Docile made me realize how egregious the relationship between genre fiction and sexual consent has been, not just in my lifetime, but forever. The book’s tagline, “there is no consent under capitalism,” struck me as pithy internet socialism at first blush.

And then I thought about it. Rape and assault are conflict; no less compelling or useful than any other kind of crime or violation for the purposes of introducing tension to a narrative. Consensual sex isn’t conflict; it stands outside of the classic model of conflicts we are taught when we begin to read critically.

I thought about my late teens and early twenties, when I had no money and nowhere to go. I thought about the places I had stayed and the people I had allowed access to my body in order to be tolerated. Where had I learned that was acceptable? How could any of us ever truly give our full consent as long as the body is a commodity that must (to some extent) be sold for survival? This was a galaxy-brain moment for me; almost every fairy tale princess is coerced through economic pressure to submit her reproductive capacity for a chance at enough to eat. It wasn’t just the scenes I knew were rape; it was everything. Without real equality, we are all giving our consent under coercion, in fairy tales and in real life.

Szpara is writing about something bigger than the lack of consensual sex in genre fiction. He is writing to change the world.

There is rape in Docile. There is no other way to put it: main character Elisha sells himself into a system of institutionalized rape enabled by extreme class inequality. What follows is confusing. Elisha is attracted to Alexander. Alexander humiliates and cossets him by turns. The sex acts that take place between them are many, varied, and described in beautifully graphic detail. Szpara has an uncommon courage among writers; he us unafraid to write queer sex in a genre novel that is erotic and essential to the plot.

It’s also rape. It’s not the violent ideal of narrative rape I was raised on. Instead, what happens to Elisha is rape as too many people experience it. Alexander exerts almost absolute power over Elisha; personally, financially, emotionally, and physically. Elisha cannot truly give consent, even when he says yes, even when he appears to offer himself to Alexander, because he is not free.

Elisha’s ordeal is not limited to the complicated feelings he has for the man who owns him, or what he’s forced and coerced into doing. Alexander, exhibiting the corruption that always accompanies absolute power, exposes Elisha to the cruelty of others. Elisha is raped and assaulted by rich people whom Alexander allows access to him. Elisha’s personal autonomy is eroded and then obliterated. He is not taken apart by Dociline, like his mother. Neither is he damaged because he refuses the drug, as he is warned he might be.

Ultimately, Elisha’s sense of self is damaged because that is what rape does. It takes a person’s self-concept and subjects it to brutal reckoning and the heinous robbery of one’s dignity. It is the ultimate depersonalization, and through it, Elisha loses the ability to choose for himself, to sense his own desires, or know himself without ownership.

Here’s where I had to take a break from this book as if I were surfacing out of deep water. None of the countless books and movies and TV shows that had shown me rape in a fictional universe had reckoned with this part of the story. The victim’s sense of self does not come into the narrative, as the narrative is focused on the hero. (That’s often because the victim is a woman and women are not commonly written as people, but that’s another essay.)

During and after a tense courtroom struggle for autonomy, Elisha has to rebuild himself. Szpara is unsparing in showing us that trauma and that struggle. In settings both public and intimate, our protagonist has to process the guilt, the shame, the anger and sadness of what this ordeal has done to him. I don’t want to give away too much of the intricate, gorgeous plot of the novel but this is, again, integral to the story. There’s a perfect marriage here between the personal, the political, and the peripeteia.

Part of this rebuilding process involves Elisha reclaiming his own sexuality with an equal partner. This is where Szpara really goes into uncharted territory for SF/F/H writing: the scenes are not only sexually explicit, but also precise on the subject of consent. Elisha and his partner talk through consent to specific acts, degrees of acceptable indulgence, and even choices of language during the interlude.

I had to put the book down. More than once.

Readers of romance are way ahead of me here, I know. But I had never read anything remotely like this. Science fiction and fantasy novels often allude to good sex with a furtive sort of adolescent shame; an elbow to the ribs in a tavern, a knowing grin and say no more. Literary novels include skims of embarrassing and unsatisfying sex with regularity. And rape is represented across the board in every possible style: graphic, eroticized, gratuitous, suggested, inchoate, even laughable.

Never have I ever read a science fiction novel containing detailed scenes that could serve as a model for how adults on equal footing might negotiate their way toward an equitable, titillating, and satisfying sexual encounter where everyone involved is giving their fully informed consent to everything that happens. Consent is not only obtained once, but in an ongoing manner. It is treated with seriousness and gravity, but the mood is not damaged by this work. Szpara’s work skillfully creates an atmosphere where consent is sexy and still mandatory, and the sex is always relevant to the plot. It is masterful, instructive truth contained inside fiction.

Consensual sex does not contain conflict in the classical sense the way that rape can. However, in a societal order such as ours wherein rape is tolerated and tacitly ignored, recovery from and defiance of rape as a way of life absolutely does contain conflict. Elisha is in conflict with a society that allows for the brokerage of his consent under the duress of inescapable debt. Within that framework, any sex that honors him as a human being and allows him to say no is a revolutionary act.

In order to have something we’ve never had before, we have to do something we’ve never done before. In order to dismantle rape culture, we have to call out the terror that must be stopped. So many voices are doing that already, but it’s not enough. We also have to be able to imagine what comes next. We have to see what the world would look like without it.

Our ability to imagine comes to us shaped by the art that we’ve taken in all our lives. Most of us know what we’re up against, but it takes a dreamer to show us what we could be fighting for.

Szpara is the rare kind of writer and dreamer who is capable of doing both. Docile is a book that doesn’t settle for something to fight against; it gives Elisha (and us) something worth fighting for. Elisha’s life, free of coercion, free of the burden of debt, free to say yes and free to say no, is something worth fighting for.

A world where people become adults more accustomed to reading hot consensual sex scenes in all genres of fiction, rather than gratuitous rape scenes is worth fighting for.

Alexander, the smooth sexy billionaire villain of the story tells Elisha to make coerced sex under conditions of ownership feel more like textbook rape by force, as an erotic game. “I want you to resist me,” he says. “Fight back.”

In that voice I heard the entire silky patriarchal chorus of the canon of genre lit. I heard the cozening Shinzon and the screaming Reavers. I heard the laughter (indelible in the hippocampus) of Gregor Clegane or Ramsey Bolton. Most of all, I heard a challenge. Elisha fights, first in bed and then for his life. First for someone else’s fun, and then for his safety and survival.

We have to fight everywhere. In books and movies and TV and our conversations and our lives. Szpara is fighting the way author Teju Cole says we must: “Writing as writing. Writing as rioting. Writing as righting. On the best days, all three.”

Pick up this pink book if you’re ready to join the fucking fight.

Docile is available from Tor.com Publishing.

Read an extended excerpt here.

Meg Elison is a Bay Area author and essayist. Her debut novel, The Book of the Unnamed Midwife, won the 2014 Philip K. Dick Award and was listed as a Tiptree Committee recommendation. Additional novels in The Road to Nowhere series include The Book of Etta and The Book of Flora. She is the first college graduate in her family, after finishing her BA in English at UC Berkeley in 2014. She spoke at her graduation. She writes like she’s running out of time and lives in Oakland.