In this scattershot series, we’ll be delving “too greedily and too deep,” prying gems out of the glorious rough that is the extended legendarium of Tolkien’s world. This includes drawing on The Lord of the Rings itself, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, The Children of Húrin, and the History of Middle-earth (or HoME) books.

As Tolkien-reading humans, we already know that even in Middle-earth, all Men die at some point. Obviously. But it’s not unless we read Appendix A in The Lord of the Rings that we see mortal death referred to as something other than a tough break. The narrator calls it “the Gift of Men” when speaking of the long-lived Númenóreans. Arwen Undómiel calls this fate “the gift of the One to Men” at her husband’s own deathbed, where “the One” is essentially God, a.k.a. Eru, whom the Elves named Ilúvatar. And this all might seem strange at first, for nowhere else in Tolkien’s seminal book does he explain why death might be seen as a gift.

I’ve already talked about Elves and their “serial longevity,” as well as what that means for the propagation of their species. Because, for all their leavetaking in The Lord of the Rings, and all that talk of sailing into the West, they’re still remaining within the confines of Arda for the long haul. Arda is essentially the whole planet and even the solar system, of which Middle-earth is but a continent. The idea is that Elves grow weary as the millennia roll on, while we mortals are merely stopping in for a quick visit, tracking mud around the carpets, and then shuffling off for good.

Question is: is this how it was supposed to be for Men?

That initial “Gift of Men” reference came in 1955 with the release of The Return of the King. Years later, Tolkien’s son Christopher published 1977’s The Silmarillion, which finally introduced readers to those Elder Days that wise-guys like Elrond were always talking about—the events of thousands of years before even the forging of the One Ring. In that epic book, the narrator gives us some imperious wordage concerning the “doom” (that is, the destiny or endgame) of Mankind, equating death with an inexplicable sort of freedom that Elves can’t rightly understand. Death mystifies even the Valar, those godlike begins whom Ilúvatar had placed as the overseers of Arda, and so the Valar tend to keep Men at arm’s length (quite unlike the Elves, whom the Valar try to gather close to themselves—to mixed reviews).

Buy the Book

The Unspoken Name

So what’s the deal with mortal death in Tolkien’s world—is it a good thing or isn’t it? As with most big mysteries, the answer depends on who you ask. But here’s the thing: to the Elf-leaning POV narrator, and probably to Tolkien himself, death and freedom are married concepts when it comes to Men. In The Silmarillion, we’re told this at the very end of the first section (the Aunulindalë, “the Music of the Ainur”):

It is one with this gift of freedom that the children of Men dwell only a short space in the world alive, and are not bound to it, and depart soon whither the Elves know not.

Why is death a freedom? That’s one thing to puzzle out. It may be rooted in the fact that Arda is messed up. Marred. Infected with evil. But escaping Arda means escaping all of that evil. Elves, we know, do not truly die. Even if “killed,” they are merely rehoused within the world like Pac-Man ghosts.

But the sons of Men die indeed, and leave the world; wherefore they are called the Guests, or the Strangers. Death is their fate, the gift of Iluvatar, which as Time wears even the Powers shall envy. But Melkor has cast his shadow upon it, and confounded it with darkness, and brought forth evil out of good, and fear out of hope.

Even the Powers shall envy. That’s no small thing! The Powers are the Valar, the mightiest of beings in Arda, but even they can’t throw in the towel before Arda is done; having vowed to enter the world at the moment of its creation, they’re physically confined there until its end. Lovely though Arda is, everyone who’s effectively immortal grows weary of it eventually. Remember this when we read about what Elves think of Men’s fate.

But is that the final word on the matter? That death is an escape for mortals, a doorway to freedom somewhere outside of the confines of Arda and into the larger universe; that it is a promotion into Iluvatar’s mysterious designs? Well, if one reads no further than LotR and The Silmarillion, it kind of is. And that does seem to be where Tolkien largely landed when it came to Men in an official capacity. BUT. The Professor’s thoughts on death in his legendarium, like other matters (the cosmology of Arda, the nature of Orcs, etc.) did appear to evolve over time. He was forever rewriting and revising his unpublished works, just as he never quite settled on the final version of Galadriel’s history.

One of the best examples of this, and the deepest dive on the subject from his own writings, is the Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth, an in-world conversation from the book Morgoth’s Ring, volume 10 of The History of Middle-earth series. (Which I personally find to be one of the best.)

In Sindarin, that phrase means “the Debate of Finrod and Andreth,” as it’s literally an intellectual debate, a sort of point and counterpoint à la the Socratic dialogues, that philosophizes and speculates on the relationship between Elves and Men and how they have such different interpretations of death. Of course, the speculations therein may apply to a fantasy world, but it unpacks a subject all too familiar to the human condition. It’s not like we’ve got it all sorted out either, here on this side of the fiction/nonfiction divide.

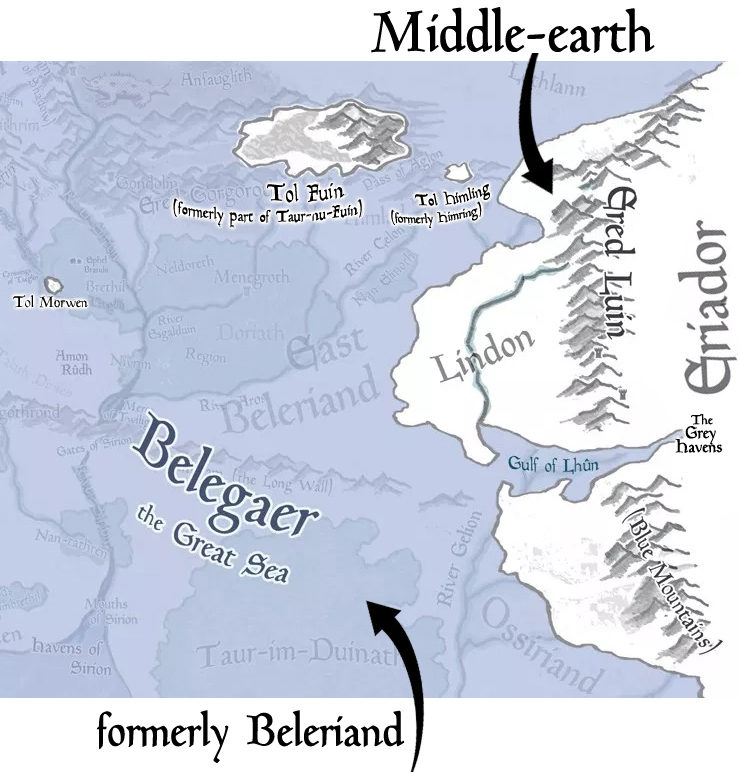

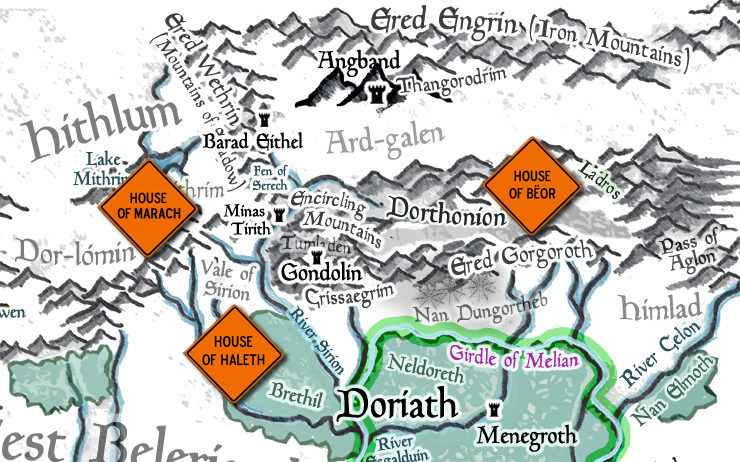

Part short story, part discourse, the Athrabeth is a friendly argument between two important characters—an Elf male and a mortal woman. It takes place in the First Age during a period of relative peace in Beleriand, that upper northwest quadrant of Middle-earth that will be long gone by the time the Rings of Power are forged in the Second Age, and an even more distant memory at the time of Frodo’s famous quest at the end of the Third. Beleriand will, in fact, sink into the Sea itself at the end of the First Age as a result of a little scuff-up called the War of Wrath.

After which the map looked a bit more like this.

In any case, the Athrabeth takes place before that cataclysm. The characters don’t know what’s coming yet. But Elves like Finrod and his brothers know that war isn’t over.

So let’s set the stage.

All is quiet on the Beleriand front. Things are peaceful because the Noldor, i.e. the High Elven exiles from Valinor, have managed to contain (at great cost) Morgoth, the Dark Enemy of the World, in his mountain fortress of Angband way up in the far north. Morgoth is called many things: the Shadow, the Enemy, the Nameless One. He is the Ainu formerly known as Melkor, once on par with the mightiest of the Valar; he’s the big bad of everything good and decent in Arda; and incidentally he’s the very being who marred it all up in the first place. Though a powerful spirit at the core, he’s locked in a physical, if dreadful body. Sauron, by comparison, is a lesser spirit and while he’s still got his own bag of tricks, he’s currently playing second fiddle to Morgoth in this day and age. Still more of a footnote than an up-and-comer.

Now, the Noldor currently have the upper hand, or at least appear to. And they do have help: The three kindreds of the Edain, the Elf-friends, have settled into Beleriand. These are all Men, and each “house” has fallen in with a particular tine of the Noldorin fork keeping Morgoth in check.

So, in this corner we have Finrod Felagund, the Lord of Nargothrond, which is one of Beleriand’s handful of hidden Elf-realms. He’s also the “wisest of the exiled Noldor,” and that’s really saying something since he’s also the brother of Galadriel. Proud and powerful the future Queen of the Golden Wood may be, but she’s just his kid sister; her wisdom and character arc still have a ways to go. It’s also an important note that Finrod himself was the first High Elf to encounter the race of Men back when they first wandered over the Blue Mountains and into Beleriand. It was his wisdom, kindness, and neighborly manner that allowed Men and Elves to start things off smoothly on the Beleriand stage.

But what I think is most important to understand about Finrod in the context of this debate: he really likes mortals. He’s their biggest fan and advocate. (For all these reasons, I continue to assert that Finrod is Middle-earth’s Fred Rogers.)

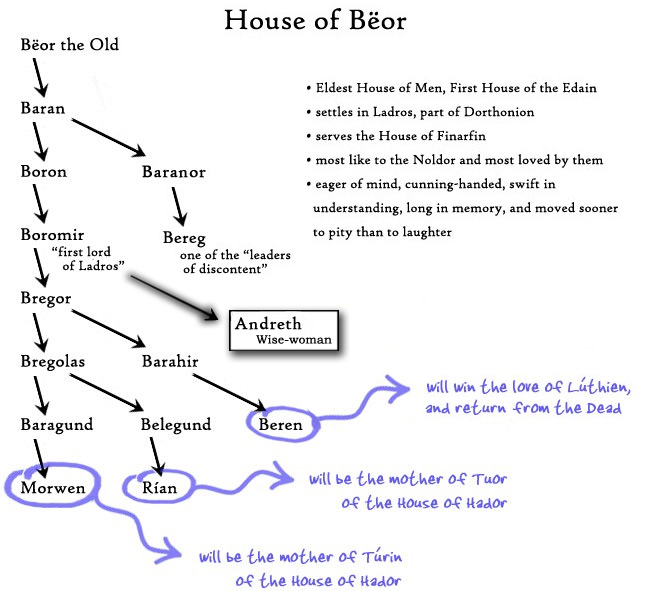

And in the other corner we have Andreth, a daughter of Men, a Wise-woman of the House of Bëor, which means she’s a lore-master among her people and high in social status. In fact, it was her family that met Finrod roughly a hundred years before; they were the first of the Edain, the Elf-friends. Interestingly, mere association with the Elves has by this time already given all the houses of the Edain longer lifespans than they’d have had otherwise. A little of that Elfiness is rubbing off. Nothing too crazy—nothing like their Númenórean descendants will someday receive—and at 48, Andreth is now middle-aged. She’s not an old woman by any stretch, but there is a touch of “winter’s grey” in her hair, and age weighs heavily on her mind… for a very specific reason, which will come to light towards the end of their talk.

Despite the royalty of her guest and friend, Andreth tells it like it is. She loves and respects Finrod and calls him lord, but she also speaks her mind openly, deferring to no one. They’re a perfect combo, because of all Elves, he is the most reasonable, the most willing to listen and have his own worldview adjusted. I get the sense that most other Elves would shoot her ideas down quickly.

Anyway, it’s a spring day roundabout the year 409 since the return of the Noldor back to Middle-earth (and the first rising of the Sun and Moon), and Finrod is hanging out with Andreth in the household of one of her relatives. This is probably taking place in Ladros, a corner of the highlands of Dorthonion, since that is where the House of Bëor settled in. Finrod is not only a lord to these Men, he’s a friend, as he had been with Andreth’s family for generations.

As to what gets them talking so deeply on this particular day, Andreth’s grandfather has just recently died. His name was Boron (no relation to the mineral with the atomic number 5) and he was the grandson of Bëor the Old.

Bëor was the chieftain whose people made first contact with Finrod. He was good buds with the Elf king, lived a good long life (for a Man), and now all these years later Finrod is friends with Bëor’s great-great-granddaughter. Her list of descendants will include Beren (of Beren and Lúthien fame). In fact, here’s a fresh look at that family tree.

Anyway, that debate…

With Boron’s passing hanging over them, Finrod and Andreth’s conversation leads naturally to the topic of death. Here follows my account of their conversation, parsed and paraphrased into a more modern style.

****

FINROD: “Andreth, I am mournful. How quickly Men grow and then pass away. Your granddad was considered pretty old for a Man, wasn’t he? It seems like only yesterday that I’d met his grandfather.”

ANDRETH: “Dude. That was like a hundred years ago. Yeah, my granddad and his had very long lives—by our standards. My people actually seem to live a bit longer than we used to, here on this side of the mountains.”

FINROD: “Are you happy here in Beleriand?”

ANDRETH: “No man or woman is truly happy, not deep down. Dying sucks, but… not dying as fast as we used to? That’s at least some tiny victory in defiance of the Shadow.”

FINROD: “Hmm, explain?”

ANDRETH: “I know you Elves have managed to lock him up in his mountain-hole up there. But…

and here she paused and her eyes darkled, as if her mind were gone back into black years best forgot.

ANDRETH: But the fact is, his power—and our dread of it—was once everywhere across all of Middle-earth. Even while you Elves lived in joy.”

FINROD: “But what does Morgoth have to do with how long you live? What defiance do you speak of? The Elves believe—and we get this firsthand from the Valar—that your lifespan comes directly from Eru Ilúvatar, the One. You are his Children, same as us, and it is he who determines your fate.”

ANDRETH: “See, now you’re talking just like those Dark Elves we met before we met you, before Bëor brought us this far west. While you High Elves have apparently lived in the Light of the Blessed Realm, your cousins on this side of the pond never have. Yet even they claim that Men die swiftly just because we’re Men. That we’re weak and we wither fast, while Elves are eternal and strong. You say that we’re Children of Ilúvatar, but we’re as frail as children to you, aren’t we? Worthy of some affection but more worthy of your pity. Elves look down from a privileged height on us.”

FINROD: “It’s not like that, Andreth. All right, some of my people feel like that—but I don’t. And when we call you Children of Ilúvatar, that’s not just lip service. It means we hold you in high regard and consider you kindred spirits, for we share the same maker. We’re closer with Men than we are with any other creatures in Arda. We love the animals and plants of this world, yes; most of them pass away even faster than you guys. We’re sad when they’re gone, too, but we know that’s part of the natural order of things. It’s in their nature to grow and perish. Yet we mourn more for Men, who are like family to us. How can you not believe, as we do, that your shorter lives are part of Ilúvatar’s design? Ah, but I can see you don’t. You think we’ve got it wrong.”

ANDRETH: “Yup. But your wrongness comes from the Shadow, too. He’s misled you and he’s wronged us. No, Men do not all agree. Most just shake their heads, don’t bother dwelling on it, and they say, “Well, it’s just always been this way and always will be.’ But some… some of us believe it wasn’t always like this. Of course, we don’t have all the facts. From what misinformation we do have, there are surely some grains of truth, and perhaps some falsehoods from the facts. We’re fairly sure Men didn’t age quickly and die in the very beginning. Take my friend Adanel of the House of Marach. Her house—unlike mine—actually clings to the name and honor of Eru Ilúvatar, yet they straight-up say that Men aren’t supposed to live so briefly in this world. That we only do because of the Dark Lord’s interference.”

FINROD: “I do see where you’re coming from. Men do suffer because of Morgoth, even in body. This is Arda Marred, after all; our world isn’t exactly running as it was meant to. His intrusion spoiled just about everything in some way—before Men and Elves even showed up. And look, even Elves sprang forth from the same messed-up world. Seriously, we’re not unaffected by him. Those of us who have settled in Middle-earth—as opposed to our relatives back in the Blessed Realm—we can feel our own bodies ‘age’ faster (if much slower than yours). Elves will be less strong, in the long run, than we were meant to be. And so, in turn, the bodies of Men are weaker than they were meant to be. That’s all true. And you’ve already noticed that you Elf-friends, who have come to Beleriand—where historically Morgoth had less influence—do live longer than your brethren in the east. And you are healthier for it.”

ANDRETH: “You’re still not getting it, Finrod. Yes, the Shadow has worsened us all, but we’re not on equal footing. Elves are set high above Men, and live on… while we die. You are strong and can keep up the fight against him. If we’re lucky we get one stab in before we keel over. But the Wise among us say we aren’t made to die like this. Death has been dealt to us. It hunts us, and we live with that fear constantly. Look, I’m realistic. I know that even if Men sailed now over to your Blessed Realm we wouldn’t just be free of death from then on. My ancestors led us this far west in hope of doing just that, in finding that Light you guys are always going on about, but we know that’s a fool’s hope. Even the Wise suspected it then, but we came anyway. We ran from the Shadow in the east only to find that he’s already here now in the west!”

FINROD: “It’s sad to hear this, Andreth. Truly. Your pride is wounded, and you’re lashing out at me. If the most enlightened of you are saying this, then things are worse than I thought. I understand why you’re rattled. You’ve been hurt. Yet your anger is misplaced. It’s not the Elves who’ve done this to you. Your lives are short, yes, but that is how it was when we found you. Your griefs and fears are no consolation to us—only to Morgoth. Beware those mistruths, Andreth! They are mingled with those grains of truth that Men hold. They are his lies, and they are meant to turn jealousy into hate. You say that Morgoth imposed death on you, but he isn’t death itself. They are not synonymous. You think running from him is the same as running from death? Do you think you can escape it? He didn’t design this world, and yet this world has death in it. Death is just what we call the process. He’s cast a pall over it and now it sounds like an evil thing itself.”

ANDRETH: “Easy for you to say. Your people don’t die.”

FINROD: “We do die, Andreth, and we do fear it—even in the Blessed Realm. My grandfather was murdered, as were many after him. Still more in the frigid crossing through the Helcaraxë in our flight to Middle-earth. And even here we have perished in war. Fëanor himself was slain. And why? Because we challenged Morgoth, because we’ve been trying to prevent him from ruling over Middle-earth. Elves have died trying to protect all the Children of Ilúvatar from him. Men included.”

ANDRETH: “But that’s not the whole story, is it? I heard that your battles with the Enemy came from you guys trying to reclaim stolen treasures. That you came back to Middle-earth not to save everyone but to get back what he stole from you. Don’t get me wrong: I know your side of the family isn’t on the same page as those miserable sons of Fëanor in this matter, but even so, what do you really know of death? A moment of physical pain, some grief, and that’s it. When Elves die they don’t leave the world but return again. When we’re dead, we stay dead. We’re goners. No takebacks. It sucks. It’s the absolute worst, Finrod. It’s not fair.”

FINROD: “So you see it as two different types of death: One, what Elves have, where it’s injury but not removal, since we may return again. Two, what Men have, where it’s injury but no relief, and no consolation. Is that it?”

ANDRETH: “Yes, but that’s not all. Elven death can still be avoided by chance or by determination. Mortal death is completely unavoidable. No matter how strong or weak or wise or stupid or righteous or evil, a Man will fall. Death is our hunter. We’ll all die and we’ll all rot.”

FINROD: “And you think this means you’re not allowed to have any hope?”

ANDRETH: “Well, we get no proof of anything, do we? Just fears and dark dreams. And as for hope… well, I guess that’s another thing.”

FINROD: “Look, we’re all capable of being afraid. I think the chief difference between my people and yours is the speed of our lives. If you think that death isn’t a thing for Elves, then you are mistaken. Elves have no idea how long we’ve actually got, how long the world itself will last. It’s not infinite. You see us as just getting started, and that our end is far off—and I grant you, to Men that would seem the case. But we’ve already got a lot of time behind us now. We aren’t so young anymore, and our end will come. The unavoidable end you speak of, we have that, too. Ours just comes later. When Arda dies, we die. If death hunts you, Andreth, know that it only hunts us slower. And when it catches us? We, too, have no certainty about what comes next.”

ANDRETH: “I didn’t know that. Even so—”

FINROD: “You will insist, I’m guessing, that at least it takes longer for death to find us, right? Well, I don’t know if that’s better or worse. Regardless, you still believe that death wasn’t part of the deal for Men. There’s much to unpack in that belief, but I ask you this: how do you think it got this way? ‘Because reasons’? ‘Because Morgoth’? You aren’t acknowledging the fact that all things in Arda are marred, that all things suffer in some way because of him. You think it’s personal, right? That it’s just Men who’re his victims?”

ANDRETH: “Sure.”

FINROD: “Then fear is what governs you, not Morgoth. The Dark Lord is terrible and strong, yes. He’s really just the worst. We know him, we remember him. I’ve seen him up close, personally, and I’ve felt the power of his voice and been beguiled. But you, Andreth… you have only secondhand accounts of him. The Elves know that he can’t truly overcome the Children of Ilùvatar in the end. He can take down individuals maybe, but not all of us. He cannot take away what Ilúvatar has given us. If he could, if he really could, then everything I know is wrong, and the Noldor are nothing, and the mountains raised by the Valar might as well be built on mashed potatoes.”

ANDRETH: “See? There. You really don’t know what death is. When it’s just hypothetical and not before you, happening to you, it makes you despair. Men know, even if Elves deny it, that the Enemy holds all the cards in this world. The resistance of Men and Elves is futile.”

FINROD: “Don’t go there! Morgoth wants you to blaspheme this way, to confuse him with Ilúvatar. Morgoth is not in charge of this world. It was Ilúvatar who placed Manwë, the King of Arda, in charge. Andreth, please don’t despair. Don’t play into the Dark Lord’s hands, who can, yes, fill you with doubt and shame and the loathing of your own bodies in life and in death. But do you really think he could saddle immortal Men with mortality, and then down through the ages allow them to remember that alleged original immortality? Not a chance. If he could, then Arda in its entirety would be meaningless. No one can give or take immortality except Ilúvatar. So I ask you: what happened, Andreth? If you really weren’t meant to die, then what happened at the beginning to bring you to this point? Did you provoke Ilúvatar somehow? Would you tell me?”

ANDRETH: “We don’t talk about that with anyone but our own. And even our Wise aren’t all agreed. Whatever happened back then, we’ve been running from it, and trying to forget it. All we have now are legends of a time when we lived longer, though death still lurked.”

FINROD: “Is it that you can’t remember? Are there no stories at all about Men before death?”

ANDRETH: “Adanel’s people have some stories.”

→ Side note: Andreth’s friend Adanel is of the people of Marach (who’ll someday be called House of Hador and be the family that produces tragic and storied heroes like Húrin, Huor, Túrin, and Tuor). But Adanel married one of Andreth’s kin, Belemir, whose household she and her pal Finrod are having this famous debate in.

FINROD: “Do only Men know these legends, then? Do you not think even the Valar know about them?”

Andreth looked up and her eyes darkened.

ANDRETH: “How the hell would we know? Your Valar never hung out with us, and you know what? We’re just fine with that. They’ve never taught us, they’ve never summoned us to protection and to paradise.”

FINROD: “Don’t judge them if you don’t know them. I’ve been among them, in the presence of Manwë and Varda both, there in the Light of the Trees. They are set above us all, and not deserving of your scorn. That’s the sort of talk we first heard from Morgoth himself. But here is an honest question I’d like you to consider, Andreth. Haven’t you ever thought that Men might just be too… well, awesome… for the Valar to handle? Too inscrutable? I’m not trying to flatter you. You guys are something else, something special, and it’s been said that you were made by Ilúvatar for a greater purpose, something bigger than Arda. So if you won’t confide in me about what might have happened to Men in the early days, at least be careful that you don’t point fingers wrongly. But come on, let’s talk about this hypothetical early state of Men, when your people did not die. You think you were like Elves in this regard?”

ANDRETH: “The tales don’t include Elves at all, not even for comparison, since in those early days we didn’t even know about you yet. Life was only about avoiding death for us.”

FINROD: “Truth be told, I’ve taken your belief of Men having never been meant for death as a pipe dream, inspired by your envy of the Elves. You’ll probably deny it. But before you came to Beleriand, you did meet and make friends with Dark Elves, right? Weren’t you… well, already mortal by that point? Did you talk with them about living and dying? It shouldn’t have taken too long for you to realize that they didn’t age, and for them to see that you did. Right?”

ANDRETH: “I think we were mortal when we first ran into those eastern Elves… or maybe we weren’t. Our stories aren’t that clear, and we had these legends before we met any Elf. We remembered that we weren’t meant to die. And by that, Finrod, I mean that we remembered that we were meant to inherit everlasting life. With no talk of endings.”

FINROD: “You realize that’s weird, don’t you? What you’re saying about the true nature of Men.”

ANDRETH: “Is it? Heck, our Wise say that no living things should be dying.”

FINROD: “No living thing? That’s crazy talk. First, you’re claiming Men once had indestructible bodies and therefore weren’t subject to Arda’s own laws of nature—though Men’s bodies are made from and fed by the very substances of Arda. Second, you’re claiming that the relationship between Men’s spirits and their bodies was out of whack and has been since the start. Yet the unity between spirit and body is essential to all us Elves and Men (and I suppose even Dwarves). All Children of Ilúvatar.”

ANDRETH: “Indestructible bodies? Yes, we have our own explanation for that. But no, we don’t know anything about this spirit-and-body harmony. True enough.”

FINROD: “Then you really don’t know yourselves for what you are. We’ve come to know you well over the course of three generations. We’ve seen you up close. One thing we know for sure is that your spirits—what we call the fëar—aren’t quite like ours. Nor is Arda your true and forever home. We know Men love this world, often as much as we do, but not in the same way. You love Arda like a vacationer, seeing everything as exotic and new, but as ones who will soon move on from it. We love Arda as our homeland; we are familiar with it already and will remain here, and that makes it precious to us.”

ANDRETH: “We are just guests here, then.”

FINROD: “Basically, yeah.”

ANDRETH: “Condescending as ever! Look, if we’re just on holiday, and you see this land as your country and not ours, what land is ours? Where did we come from? Tell me that.”

FINROD: “You tell me! How can we possibly know? We are bound to this world and have no yearning that reaches beyond it. You know what we Elves say about Men? We say that everything you look at it, you look at only to discover the next thing. That if you love something, it’s only because that thing reminds you of something else, something you like more. Well, where are those other things? Look, Elves and Men were both born into this world first, so any knowledge Men have has to come from here, doesn’t it? So where is this memory, this echo, of some other existence that you have? Not from anywhere in Arda—I can tell you that. We Elves have traveled far, too. If you and I both trekked back to the far east, to the cradle of your civilization, I would still feel that to be part of my home. Yet I would see wonder in your eyes, the same as I see from Men born here in Beleriand.”

ANDRETH: “Finrod, you keep saying awfully weird things I’ve never heard before. Yet… there is something familiar in it. This elusive ‘memory’ that we have, as if from some other place and time—it comes and goes. We who’ve known and loved Elves have a saying: ‘There is no weariness in the eyes of the Elves.’ And yet Elves can’t understand when we also say ‘Too often seen is seen no longer.’ I guess we equate a long relationship with a stale one. The seeming immortality of the Elves gives you an energy we associate with children, and I guess that makes us feel like adults by comparison. We’re jaded now, and the world loses its luster before long. Doesn’t that sound like something that comes from the Enemy? Or do you think we’re meant to lose that childlike wonder, right from the start?”

FINROD: “Morgoth may have cast a pall upon everything for you, making you wearier than you ought to be and turning that weariness into scorn, but the restlessness of Men was always there. That I believe. Do you see why I spoke of the spirit and body being out of whack? Death is the splitting of spirit and body. Not being made to die means not being made to have your body and your indwelling spirit ever separate. That doesn’t make sense to me. If Man’s spirit is merely a guest in Arda, why place it in a body it can’t ever leave? But, you think even a mortal’s body was meant to stay put, and not release her when her vacation on Arda has ended?”

ANDRETH: “We’d have an awful low opinion of our own bodies if we accepted that—that they were meant to be cast away so lightly. We’re not just hopping from body to body here. We each get one body for one life; call it a house, call it clothing. It’s tailored to our spirit, or maybe our spirit is tailored to it. The separation of body from soul isn’t our norm—and I stand by that. If it was, I guess, yeah, we’d be out of whack. It wouldn’t be our housing or our clothing; it would be a chain. Not a gift. And by the way, who do chains make you think of? Anyone? Oh, but you told me not to go there.… Well, you know what? Screw that. In our darker moments, we’ve said these things. Death doesn’t just suck. Death shouldn’t be.”

FINROD: “Mind: blown. If what you say is true, then your traveling spirits are truly and irrevocably bound to your bodies within Arda. And that would mean that when your spirits do leave the world, they must be able to take with them the very bodies they inhabit—right up and clear out of Arda altogether. And if that’s the case, then those parts of Arda Marred that your bodies were made from would have to become unmarred. And that’s beyond everything the Valar ever saw in the Music, way, way back when. Which would be incredible. And damn, how powerful indeed did Ilúvatar make you, and how unspeakably horrible was Morgoth’s alteration of this original design? Hmm. And so that, in turn, has me wondering: does Mankind’s restlessness come from comparing the world as it is with the world as it ought to be? Or simply a different world altogether?”

ANDRETH: “Eru only knows, I guess. How could we ever figure it out here, in this world of deceptions? In Arda Marred, as you call it. Not enough Men even think about the whole world or those we share it with. I admit we mostly think about ourselves. Men dwell on what we’ve lost, on what we think we’re supposed to have versus what we’ve been dealt.”

FINROD: “Hah! High Elves aren’t so different. But you know what? This gives me hope. It really makes me think. Maybe—just maybe—Men were meant to be the ones to heal the hurts of this world. Maybe that was your purpose. The Elves have called you the Atani, the Second People, the Followers. But what if you’re the Fulfillers? Agents of Eru Ilúvatar, designed to make better that Music that foretold the world, to expand that great vision itself. Maybe it’s not so much establishing Arda Unmarred as helping to bring about a third iteration of Arda altogether. Something new and greater. Did you know that I’ve spoken with some of the Valar myself—they who took part in the Music of the Ainur, who saw and helped to shape the world that was yet to come? But I don’t know: did they even reach the finale of that Music? Maybe that’s why they don’t know everything, or fully understand your part to play in it all. Or geez, maybe Ilúvatar straight-up ended the music before it was finished, withholding the full composition! In which case, we’re all in the same boat: Valar, Elves, Men. None of us know how the story is going to end, do we? Ilúvatar has yet to give us the final reveal, and has offered us almost no spoilers. It may be that he wishes us to help determine the end—to make it all the more wonderful. If he’d given the Valar a full synopsis, which he didn’t, then the end would be predetermined.”

ANDRETH: “So, what’s your prediction, then? What’s in our world’s season finale?”

FINROD: “Ah, clever girl. But I’m an Elf, so even I am thinking too much of my own people. My thought is, of all the Children of Ilúvatar, Men would be the ones to end death even for the Elves. What if, at the end of Arda, it is entirely remade, and together Men and Elves would sing and dwell together at last.”

Then Andreth looked under her brows at Finrod.

ANDRETH: “And when you Elves weren’t turning everything into a freakin’ song, what would you actually say to us then?”

Finrod laughed.

FINROD: “Oh, who knows? Sweet Andreth, you know how we are. We’d probably be yammering away about the past—we’re big on nostalgia—recalling all the epic dangers and glories of the Arda Marred of the distant past. We’d tell you even then about the Silmarils. Of days when we were on top. But you guys, you would finally be at home! You would belong, truly, and you wouldn’t need to look elsewhere anymore. You would be on top. ‘Those Elves are always running at the mouth about other places and times,’ you would say! And we would. Because memory is our specialty. But from this burden comes great wisdom, even as this current Arda rolls on.… ”

And then he paused, for he saw that Andreth was weeping silently.

ANDRETH: “Such talk of future wonders. But what are we to do now? Men are on the decline here and now. We’re dropping like flies. There is no Arda Remade for us. Only darkness and death that we cannot see past.”

FINROD: “Do you hope at all?”

ANDRETH: “What is hope? Expecting a good outcome based on only a very small foundation? No, we do not have even that.”

FINROD: “There are two varieties of hope. One the Elves call Amdir, which means ‘looking up,’ but the deeper hope is Estel, which means something like ‘trust.’ It isn’t subject to the world’s fortunes, or the weight of circumstance, because it doesn’t come from any experience at all—it comes simply from our nature as Children of Ilúvatar. Nothing can overcome it. That is the foundation of Estel, for Ilúvatar desires the joy of his Children. And he will not be denied. It seems you do not have Amdir, but perhaps some measure of Estel?”

ANDRETH: “Maybe not. Don’t you see that is part of our condition that even Estel is lacking? Are we, as you say, Children of Ilúvatar? Or are you mistaken, and we will be discarded in the end? Or perhaps we were discarded from the beginning? Isn’t it possible that the Dark Lord is the one actually in charge here?”

FINROD: “NO. Stop saying that.”

ANDRETH: “You heard me, and you would understand if you could feel the despair that we live in—that most of us live in. Those Men who journeyed this far west did so in a vain kind of hope, and now we only hope for some sort of healing, or an escape. Is that your Estel? Or maybe it is your Amdir, but without any good reason. A foolish dream, knowing that when we awake there is no real escape from death.”

FINROD: “A dream, you say? Even dreams can be meaningful. And just having that dream might be a spark of Estel. But I think you’re confusing dreams with hope and belief. Are Men talking in their sleep when they speak of healing and escape?”

ANDRETH: “Either way, it doesn’t make much sense. I mean, what form would this healing take, and what about those of us who’ve already perished in death? Only those Men in the ‘Old Hope’ camp would even try to guess at that.”

FINROD: “Wait, what? What’s this ‘Old Hope’?”

ANDRETH: “It’s something that a few folks hang onto—though, there are more of them now that we’ve come to Beleriand, because at least we can see that the Dark Lord can be resisted. We didn’t see so much of that where we came back east. But it’s not much to cling to, really. Resisting him doesn’t undo any of the damage. We’re still dying. And if the Elves aren’t ultimately triumphant against the Shadow, our despair will be all the greater. Our hopes were never grounded on the strength of Men, or anyone else, really.”

FINROD: “Well, what do these Old Hopers say?”

ANDRETH: “They say that the One—Eru himself—will one day come into Arda directly and heal Men and all the evils that ever were. And they say, or pretend, that we’ve had this belief since the beginning, back when things went horribly wrong for us.”

FINROD: “Pretend? Do you believe none of it, Andreth?”

ANDRETH: “There’s just no evidence to support it. Who truly is the One, this Eru Ilúvatar? Discounting all the Men who’ve fallen into the service of the Dark Lord, the rest of us still see a war-torn world split between light and dark, and neither side is the greater. I know, you’ll say that’s just Manwë and Morgoth we’re thinking of, and that Ilúvatar is above them both. But isn’t the One then really just the most powerful of the Valar, a god among gods? Even Men think of Eru as an absentee king living far outside his own realm, leaving lesser lords behind to govern in his place. And yeah, I know, you’ll say, hey, Eru Ilúvatar is the real and uncontested heavyweight champion, and he made the whole universe, blah blah blah. Right?”

FINROD: “Of course. We accept that—the Elves and the Valar are all on the same page on this point. Only the Enemy says otherwise. Who are you going to believe: the ones who demand zero worship from you, or the one constantly trying to rule the world and set himself above all?”

ANDRETH: “I hear you, which is why this Hope is a hard one to grasp. But I wonder how could the One enter into the very thing he has made, when he is himself far greater. Can a storyteller enter his own story? Can an artist enter her own painting?”

FINROD: “What if he’s already part of it, within and without?”

ANDRETH: “Are you saying he can exist within the very thing that springs forth from himself? The people I’m talking about say he’ll enter personally into Arda. That sounds like something different than what you’re saying. Wouldn’t that break Arda, if not the whole universe?”

FINROD: “Well, that’s above my paygrade to understand. Possibly above the Valar’s, too. I think you’re getting caught up in semantics, though. You’re talking physical dimensions, as if ‘greater’ necessarily requires tremendous size. None of that is likely to apply to such a being. If Ilúvatar wanted to enter Arda in body, I’m sure he could do it, though I can’t rightly imagine it myself. In entering his own work, he would still be its creator. But I confess, without his direct hand I can’t imagine how else this healing could be accomplished. He won’t simply let Morgoth claim ultimate victory over Arda. But I also know there is no power greater than Morgoth except Ilúvatar. So if he will not give Arda up to Morgoth, he will have to come here in some fashion to topple him. That said, even if Morgoth did get the boot, his Shadow would probably remain and grow if not properly countered. I think that defiance must still originate from outside Arda.”

ANDRETH: “Finrod, would you… Would you believe in this Hope, then?”

FINROD: “I don’t know yet. It is still a strange and new concept to me. Nothing quite like this was ever spoken to the Elves. Only to you. And yet… I am hearing it from you now, and that lifts my spirit. Yes, Andreth, a Wise-woman you are: Maybe it was meant to be that Elves and Men would come together to compare notes in this way, and in this way the Elves would learn of this new Hope. That you and I specifically were meant to sit and talk just like this—despite the gap between our people—so that while the Dark Lord might still brood nearby, we needn’t be afraid.”

ANDRETH: “The ‘gap between our people’! Are mere words the only thing that can span it?”

And then she wept again.

FINROD: “I cannot say. That gap is made by the difference in our fates only. In all other ways Men and Elves are so very similar, more alike than any other creatures in this world. But that’s a perilous gap, and attempting to bridge it is dangerous and will bring only grief. To both. But why do you say ‘mere words’? Is that nothing? Words are powerful, not trivial sounds. Haven’t we grown closer because of the words we’ve shared? Doesn’t that comfort you some?”

ANDRETH: “Comfort? Why would I need comfort?”

FINROD: “Because time, and the fate of Men, weighs heavily on you. Do you think I don’t know why? Aren’t you even now thinking about my own dear brother? Aegnor, the Sharp-flame, swift and eager. It wasn’t so long ago that you two first met, when your hands touched in the dark. You were just a young maiden then, yourself brave and eager, there in morning of your life upon the tall hills of Dorthonion.”

ANDRETH: “Why stop there, Finrod? Go on. You were going to say ‘But now you’re a wise-woman, old and alone, and while the years have not touched him they’ve already put winter’s grey in your hair.’ Well, you don’t have to say it now. Because he once did.”

FINROD: “I know. That’s the sting of it, dearest mortal. And it’s this bitterness that lies beneath everything you’ve said to me, isn’t it? When I try to speak comfortingly to you, you call it haughty, because I stand on this side of the gap. What else can I say, then, except to remind you of the very Hope you have revealed to me?”

ANDRETH: “It was never my Hope! And even if it were, I would still weep. Why is this pain thrown on us as well? Is death not enough? Why must we love you, and why in turn would you Elves love us (if you even do), while this rift lies between us?”

FINROD: “Because despite all else, we were made much alike, your kind and mine. We didn’t make ourselves the way we are, and it certainly wasn’t Elves who made the rift. No, Andreth, we aren’t the masters of this division, but we’re full of pity for it ourselves. I know, that word irritates you. But there are also two types of pity. The first is like empathy, the shared sorrow of close kin. The second is mere sympathy for another’s sorrows, but which cannot be felt. I speak of the first.”

ANDRETH: “I want none of it. I was once young and I looked upon your brother’s fire and vigor, but now I am old and lost. He was youthful and his flame came near to mine, but he turned away at last, and all these years later he is surely still young. Do candles ever feel sorry for moths that are drawn to them?”

FINROD: “Do moths ever feel sorry for candles when they’ve been blown out? Andreth, understand this: Aegnor loved you. Truly. And because of you, he will never seek an Elvish bride; he will remain unwed, remembering your time of youth in Dorthonion. All too soon his flame will go out. I foresee it. And you, mortal woman, you will live long for your kind—and he will not.”

Then Andreth stood up and stretched her hands to the fire.

ANDRETH: “Then why did he leave me, while I still had years of my youth remaining?”

FINROD: “You might not understand this because you are not an Elf. Although we have Morgoth contained, it will not last. Neither Aegnor nor I believe that we’ll keep the upper hand against our Enemy. And in times of war Elves do not get married and have families. We prepare for battle or for retreat. Now, if Aegnor followed his heart, he would have taken you and run from this place, leaving his entire family and yours behind. But he is loyal. What would you have done? You said yourself that there’s no escaping.”

ANDRETH: “I would have given everything I have—my family, my youth, even what hope I have—for one more year or a single day in his company.”

FINROD: “He knew that. And that is why he turned away. The cost of such a naïve trade would be pain beyond your understanding. No, if ever there was marriage between an Elf and a mortal, it would have to be for a higher purpose than even love. For some destiny I cannot foresee. And even that would be short-lived and painful in the end. Death is less cruel.”

ANDRETH: “For mortals the end is always cruel—what else is new? But Aegnor… I would not have dragged him down. When my youth was done, I wouldn’t have limped after him as an old woman, trying to keep up with his youthful pace.”

FINROD: “You say that now. And he would not have run ahead of you, anyway. He’d have stayed at your side, helped you walk. Then you’d have felt his pity in every moment. Aegnor didn’t want you to feel so ashamed. Andreth, you may not understand this, but Elves love the most within our memories—and we would rather have a good memory that has been shortchanged than one that runs long but ends poorly. Aegnor will always remember you in the daylight of your youth, and on that last night by the Blue Lake when your reflection caught starlight. He remembers it now, and he will remember it in the Halls of Mandos after he is slain in battle.”

ANDRETH: “What about my memories? Will I get to bring them into any halls with me? Or do I go into darkness, where my memory of him will go out. At least… at least I might forget the memory of his rejection.”

Finrod sighed and stood up.

FINROD: “The Elves have no words to erase such thoughts, Andreth. Do you wish we’d never met—Elves and Men? That you’d never seen that flame or known his love? Do you think you have been spurned? You haven’t. That falsehood comes from the Dark Lord. Reject his lies, and our talk today doesn’t have to mean nothing. But I must go now.”

Darkness fell in the room. He took her hand in the light of the fire.

ANDRETH: “Where to?”

FINROD: “North, towards Angband, where swords are needed and war awaits still. The siege still holds, and the natural world lives on in freedom, but the night will come soon.”

ANDRETH: “Aegnor will be there with you, won’t he? Tell him, Finrod. Tell him not to be reckless if there is no need.”

FINROD: “I will. But that’s like telling you not to mourn. My brother is a warrior through and through, and his anger against the Enemy is unquenchable. It’s the Enemy who’s brought this darkness on the two of you and on us all. But you’re not meant for Arda forever. Wherever you do go—beyond this world—I hope you find light. Maybe you can wait for us there, for my brother and for me.”

****

Here the “Debate of Finrod and Andreth” ends, in a solemn moment between old friends. If you hadn’t already known about the relationship between Andreth and Finrod’s brother Aegnor, it sort of comes out of nowhere (in a meaningful way): a small but poignant love story against the wide backdrop of mortality. But suddenly we can understand (as does Finrod) the underlying spite in Andreth’s words. She laments not merely that all Men must die, but that she must be forever separated from the one she loves.

It’s fascinating, and of course sad. As Tolkien readers, we’re more accustomed to the pattern of mortal Men falling in love with Elf maidens. And even those are rare—only three times are there any such pairings—yet each results in an arguably hard-won (but inevitable?) marriage. Beren and Lúthien. Tuor and Idril. Aragorn and Arwen. But with Andreth we have a mortal woman and an Elf male, and yet they are not to be. There is no “high doom” laid on them, as Finrod calls it, and it’s all the more heartbreaking for it. Even as we learn about them, it’s already been “over” for years. Aegnor had turned away from her, and they haven’t seen each other since, much to the sorrow of both. Yet he will have eyes for no other, not even in Valinor when he is inevitably slain—he’ll remain a bachelor through to the end of Arda.

Forty-six years after this talk, Morgoth does finally bust out of Angband—as Finrod and Aegnor knew he would. The Dagor Bragollach, or Battle of the Sudden Flame, commences. Morgoth brings out the big guns, up to and including rivers of lava, massive armies of Orcs, dragons, and the Balrogs.

And in the first wave of battle the sons of Finarfin—Finrod, Angrod, and Aegnor—meet their fates. Some more tragic than others. From The Silmarillion:

The sons of Finarfin bore most heavily the brunt of the assault, and Angrod and Aegnor were slain; beside them fell Bregolas lord of the house of Bëor, and a great part of the warriors of that people. But Barahir the brother of Bregolas was in the fighting further westward, near to the Pass of Sirion. There King Finrod Felagund, hastening from the south, was cut off from his people and surrounded with small company in the Fen of Serech; and he would have been slain or taken, but Barahir came up with the bravest of his men and rescued him.

That’s Barahir of the House of Bëor, Andreth’s kin. Finrod swears an oath to Barahir that will lead us invariably to Beren and Lúthien and pretty much every important event from there on out. As for Andreth, she does live long like her fathers of old; she is about 94 when the Battle of Sudden Flame begins. Concerning her end, Tolkien is vague in his sometimes almost comically unsure fashion:

(It is probable, though nowhere stated, that Andreth herself perished at this time, for all the northern realm, where Finrod and his brothers, and the People of Bëor, dwelt was devastated and conquered by Melkor. But she would then be a very old woman.)

As to that “Old Hope” that Andreth had talked about that? That curious idea that Men had about Ilúvatar himself reaching into the world to fix things? It was news to Finrod, but I feel there is at least a hint of it within The Silmarillion.

Yet of old the Valar declared to the Elves in Valinor that Men shall join in the Second Music of the Ainur; whereas Ilúvatar has not revealed what he purposes for the Elves after the World’s end, and Melkor has not discovered it.

Perhaps this Second Music is linked to the Arda Remade that Finrod starts to get excited about in the Athrabeth. If Men somehow can bring about the Unmarring—which begins with Ilúvatar entering into Arda somehow—then maybe there is some truth to this Old Hope. But Tolkien did not lay down a firm conclusion even in this tale. He always lets the greatest mysteries sit, and they enrich the legendarium and make it… well, more like the real world, right? Had Tolkien lived to see The Silmarillion published himself (as opposed to its eventual publication under his son Christopher’s amazing stewardship), the Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth would have been part of its Appendices (just as LotR has its own) and it would have been “the last item” therein. So Christopher observed from one of his father’s notes.

Also, it isn’t Finrod alone who contemplates and accepts this idea that Men may be key to the eventual salvation of the world. Perhaps he does share much of what he learned from Andreth with his people, because though it’s never so explicit as all that, we can read in various places that the Elves certainly accept that their “dominion” will end even though they’re the ones sticking around for the full duration; they come to accept that Men are meant to take over. We as readers first heard it from Gandalf at the end of The Return of the King when he is speaking to Aragorn:

‘And all the lands that you see, and those that lie round about them, shall be dwellings of Men. For the time comes of the Dominion of Men, and the Elder Kindred shall fade or depart.’

But even in Morgoth’s Ring, we can see that other Elves after Finrod come to accept it, though they are rightly baffled by it. In one of the post-debate notes concerning the Athrabeth, Tolkien writes:

The ‘waning’ of the Elvish hröar must therefore be part of the History of Arda as envisaged by Eru, and the mode in which the Elves were to make way for the Dominion of Men. The Elves find their supersession by Men a mystery, and a cause of grief; for they say that Men, at least so largely governed as they are by the evil of Melkor, have less and less love for Arda in itself, and are largely busy in destroying it in the attempt to dominate it. They still believe that Eru’s healing of all the griefs of Arda will come now by or through Men; but the Elves’ part in the healing or redemption will be chiefly in the restoration of the love of Arda, to which their memory of the Past and understanding of what might have been will contribute. Arda they say will be destroyed by wicked Men (or the wickedness in Men); but healed through the goodness in Men.

But we’re not quite done with the topic of Men and death. See, Andreth suggested that her friend Adanel—wise-woman of the House of Marach—had more to tell about those early days of Men. Which really intrigued Finrod.

‘Therefore I say to you, Andreth, what did ye do, ye Men, long ago in the dark? How did ye anger Eru? For otherwise all your tales are but dark dreams devised in a Dark Mind. Will you say what you know or have heard?’

In the sequel to this topic, we’ll talk precisely about that time, long ago in the dark. Or at least, how Men tell it.

Top image from “Grasping in the Dark” by IsabelStar.

Jeff LaSala is grateful to fellow Tolkien geeks like Tanya Plashkova and Shawn Marchese for helping out with some finer points of the Athrabeth context. Aside from nerding out about Middle-earth with such writings as The Silmarillion Primer, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes sputters about on Twitter.