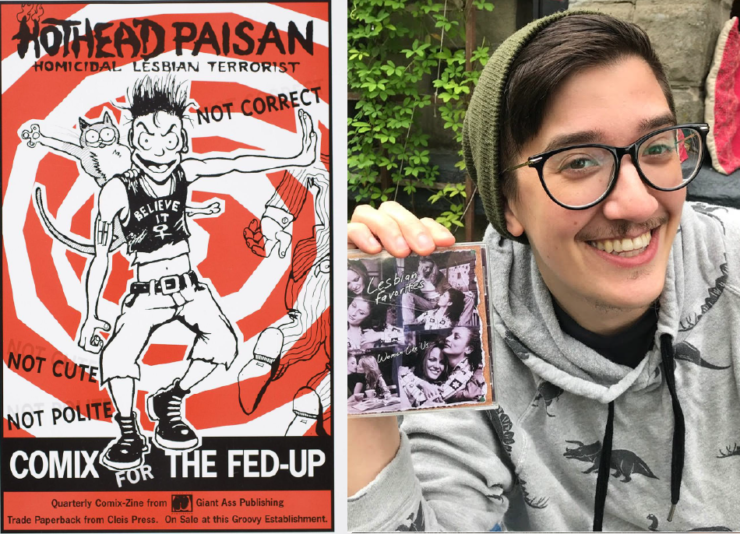

I first encountered Hothead Paisan in a Borders Bookstore when I was fifteen.

At the time, I was a lonely teenager. I’d changed schools twice in two years and drifted away from most of my old friends. I’d lost another handful of friendships to the burgeoning opioid epidemic. Of the local kids I knew, one later died of an overdose, two wound up in prison, and another cycled through rehabs for years.

The early 2000s were a weird, uniquely terrible time, and I have no idea why people are trying to rehabilitate them as cool. Anyway. Borders Books.

That Borders happened to be across the street from where I switched buses on my long commute back and forth from school. I wasted hours in the SF/Fantasy section, where I read every Orson Scott Card book and X-Files tie-in novel they carried; in the skimpy graphic novels shelves, reading through Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Preacher trades and the Cataclysm and No Man’s Land arcs in Batman. I picked over the photography and art books, thumbed through Steal This Book and The Communist Manifesto, and thoroughly investigated their poetry section. I was looking for something I couldn’t quite articulate: distractions, definitely, but also recognition, familiar characters and landscapes. Someplace I could both escape to and find myself.

I found all these things when I laid my eyes on the cover of The Complete Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist. The cover depicts Hothead—a butch, grungy dyke—barreling down on the viewer. She has an ax clutched in both hands, shotgun slung over one shoulder, knife tucked into one of her combat boots. Her cat, Chicken, is jogging alongside her. Both of them are smiling; Chicken with feline amusement, Hothead with a gleefully violent glare.

I tucked the book under my arm and walked out without paying.

Sorry, Diane DiMassa! If you’re reading this, I’ll paypal you the $30 I owe you. But in 2000, I was a broke, half-feral teenager, and I desperately needed that book.

***

The Complete Hothead Paisan collected DiMassa’s irregularly-produced underground comic series. DiMassa later admitted that she started the comic while in addiction recovery, as a place to channel her rage at the misogynist, homophobic world. An article on Autostraddle quoted DiMassa’s author bio, saying that she “started out as a nice little Italian girl in patent leather shoes, discovered rage, discovered alcohol, progressed, dropped the bottle, kept the storm cloud, and now somehow manages to make a living out of having her secret fantasies and demons made public.”

Many of Hothead’s misadventures begin as vengeance for the indignities of living in a toxic, patriarchal society. It’s not a dystopia exactly, in that it’s not a secondary world or warning about the near-future; it’s our world, through rage-tinted glasses. Hothead usually minds her own business until she can’t; until a suit yells at her to get off the sidewalk, or catcallers scream at her, or she overhears a court setting rapists free and charging the victim a $5000 “temptress fee.” But DiMassa also presents Hothead as an addict, whose rage benders are triggered by awful television, not sleeping, isolating herself, and drinking too much coffee.

At fifteen, I’d spent years swallowing my rage until I choked on it, until it erupted in fights in school or petty vandalism. There was never any shortage of things to be angry about. Sexual assault and domestic violence were pretty common amongst the kids I grew up with. I saw my friends get sent home from school for wearing spaghetti strap tank tops to school. My math teacher told the entire class I was failing. I got suspended for throwing a pencil to a classmate in the gym. I witnessed queer friends disappear into drugs, or depression, or scared-straight programs out in Utah.

This was the same period when Vermont legalized civil unions for queer couples. For those of you who don’t remember, civil unions were off-brand gay marriages that were mostly null outside the state, but hot damn, were they exciting at the time. Their legalization incurred a massive, organized pushback from conservatives against the godless gays trying to destroy the institution of marriage by, you know, participating in it. Signs demanding to “Take Vermont Back” became a common sight in my neighbors’ lawns. Not coincidentally, it was also the year I first got verbally attacked for being queer; a boyfriend’s father started screaming at me out of nowhere, telling me that gay people were pedophiles and bisexuals would sleep with anyone.

So yeah, I had rage enough to go around.

But because I was a teenager, and because I was still read as a woman, my anger was constantly written off. Boys teased me for being on the rag, teachers told me to leave my feelings at the door, and random men told me to smile—though somehow, they always seemed to be looking at my tits instead of my face.

Unsurprising, in retrospect, that perpetually angry, Italian-American, baby queer me latched onto Hothead. I had few outlets for expressing my rage, none of them effective. Getting into actual fights wasn’t nearly as cathartic as watching an avenging queer angel take down an abusive boyfriend with a single bullet to the face. Hothead punched men’s faces into pulp. Her violence was graphic, lurid, cartoonish, yanking out rapists’ spines and chopping off their dicks. Her rage was so overpowering that it sent her into paranoid manias, stockpiling bullets and tampons for the inevitable apocalypse, or contemplating suicide when the fight felt all too hopeless.

Because Hothead is a woman of extremes, her despair is as all-consuming as her rage.

And like all queers ever, she is only ever saved through the grace of her friends. Her cat, Chicken, offers what Publishers Weekly called “the puckish wisdom of cats,” by turns talking Hothead down and tagging along on her exploits. Her friend Roz is every baby boomer lesbian that tried to enact world peace through vegetarian potlucks and chamomile tea. And Hothead’s lover, the non-cisgender Daphne, takes her on dates and makes Hothead drink water—truly an unsung champion. Maybe even more than being an outlet for cathartic rage, Hothead Paisan was my earliest model of queer community; finding people that would hold space for you, and hold you accountable.

Buy the Book

Finna

I’ve seen a few articles wondering why Hothead Paisan faded from the collective queer cultural memory. Her cult status dimmed while underground comics have been celebrated, and queer webcomics proliferated across the internet. It’s not like politics have gotten less dire for queers; despite neoliberal assurances, gay marriage didn’t solve homophobia. There’s still rage enough to choke on. Bright red bullseyes proliferate on monstrous men, who are ripe and ready for some satirical target practice.

So where’s Hothead these days? Her creator has faded from the spotlight since the mid-2000s. In the age of the Personal Brand, DiMassa seems disinclined to participate. (More power to her, frankly.) As far as I can tell, she’s got a mostly-private Facebook, a dusty Youtube channel, and a blank personal website. She seems to make a living selling fine art now, and occasionally appears at queer comics conferences.

If I had to venture a guess? Hothead’s refusal to change—the thing I loved so much as a teenager—is a turnoff now. She’s no longer a universal avatar of righteous anger at the patriarchy. She never was, really, just a very particular kind of white cis woman’s anger, which is historically unreceptive to criticism.

Hothead Paisan comics have an emotional reset: any progress or growth on Hothead’s part was inevitably set aside one or two episodes down the road. Over the course of eight years and twenty-one issues, Hothead has a number of revelations, celestial interventions, and fourth-wall-breaking meta moments. But while Hothead’s aim doesn’t waver, it never fires with any more subtlety than a firehose.

Her anger also embodies a lot of the shitty gatekeeping politics that shut people out of LGBT circles. Hothead relentlessly hectors femmes and bisexual women, for example. Trans men don’t exist in the comic at all. DiMassa refuted Daphne’s possible trans status when trans women claimed her for one of their own, and Daphne was literally erased from later iterations of Hothead. DiMassa, before she retreated from the spotlight, also made a lot of transmisogynistic comments in response to criticism from trans women.

Hothead is always exactly who she is: uncompromising, protector of Womyn, proud lesbian. Product of her time, and seemingly trapped in amber.

***

In SF/F/H and elsewhere, there’s a wish to revisit older stories to see how they hold up, if their status was deserved or maybe unearned. This has prompted endless hand-wringing about so-called “cancel culture,” as if people who are already protected by their gender, race, and current success are somehow owed our polite, uncritical attention. On the other side, there’s an urge to consign stories that don’t meet our moral standards to the void and never speak of them again.

I can’t lie: I’m glad Hothead Paisan was in that Borders when I was fifteen. I desperately needed some cathartic vengeance against the world, problematic as it was (and is). I also needed a hero I could see myself in: gender-defying and angry, feral but somehow charming. I aspired to give as few fucks as Hothead did. I even hand-dyed a bunch of shirts with slogans I stole from that comic, because nothing expresses your teenage alienation like wearing a shirt with the phrase FART QUEEN on it. (God, I miss that shirt.)

But I gave my collection of her comics away a decade ago. I outgrew Hothead. I also outgrew Preacher, Batman, and Orson Scott Card, and for mostly the same reasons: I wanted worlds, characters, and stories that were more complicated than they could give me. I was tired of trite justifications for violence, or narrow definitions of justice. And I got annoyed that these supposed underdogs dismissed or ignored or used caricatures of people like me and my community.

There was better stuff out there, so I found that instead. Kelly Sue DeConnick’s comics, particularly Bitch Planet and Pretty Deadly, and Hilary Monahan’s Hollow Girl feature women on brutal missions of revenge, but treat their protagonists’ violence with complexity and self-awareness. Realm of Ash, by Tasha Suri, deals with grief and rage stemming from generational violence.

The field, thank god, is far more fertile than I could have imagined at the turn of the millennium.

Nino Cipri is a queer and trans/nonbinary writer, editor, and educator. They are a graduate of the 2014 Clarion Writers’ Workshop, and earned their MFA in fiction from the University of Kansas in 2019. A multidisciplinary artist, Nino has also written plays, screenplays, and radio features; performed as a dancer, actor, and puppeteer; and worked as a stagehand, bookseller, bike mechanic, and labor organizer.