So, let’s talk about X-Men.

With the uneven—but gently received—Dark Phoenix gracefully bowing out of theaters, the New Mutants movie that’s still (theoretically) coming out, Disney cutting the deal that might finally fulfill fervent nerd fantasies of seeing Wolverine and Captain America on screen together, and everyone waiting on tenterhooks to see how Johnathan Hickman’s soft-reboot of the comic line injects the series with that same explosive vision he brought to the Avengers and Fantastic Four, I think it’s a pretty good time to talk about X-Men.

I recently had the pleasure of re-reading Chris Claremont’s original run of X-Men; the entire melodramatic, messy, multi-faceted sixteen years of it in all its soap operatic—and yes, occasionally extremely problematic—glory. While Stan Lee and Jack Kirby are nominally the creators of the X-Men, it was Claremont, working with tools left for him by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum, who truly invented the X-Men as we know them today. But what stood out to me while diving back into his work is that as much as this era still inescapably defines the series in popular consciousness, very little of what made it tick has actually found its way into big screen adaptations despite every X-Men movie pre-dating Deadpool and Logan drawing directly from it.

Which means there is still ample fertile ground to draw from when talking adaptation. The surface has barely been scratched! Here’s my list of ‘Ten Things From The Claremont Era of X-Men, Mostly Written by Him, That Would Be Rad If Adapted Directly To Screen Without Really Changing Much At All (NOT The Dark Phoenix Saga)’!

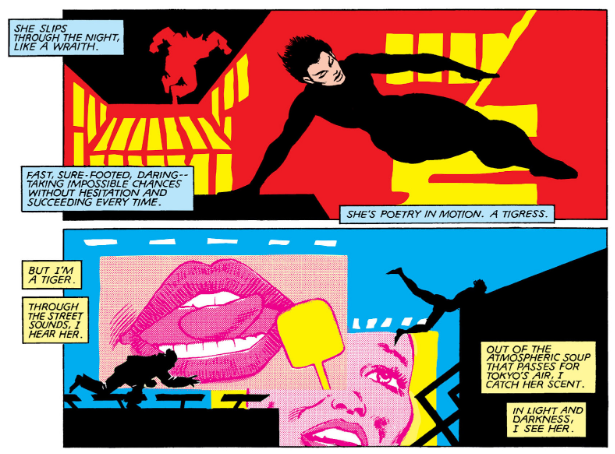

1. The Neon Cyberpunk Aesthetic

X-Men is probably one of the greatest aesthetic trendsetters in Superhero book history in ways that still reverberate even with its vastly diminished profile in Marvel’s traditional lineup. X-Men never quite managed to truly shake things up on the level of a book like Stan Lee’s Spider-Man run, or The Dark Knight Returns, but it was always cresting the wave of the cutting edge—the cool kid at the back of the classroom that everyone wanted to emulate. Claremont worked with artists like Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, Marc Silvestri, and Jim Lee near the beginning of their careers and gave them the kind of emotionally dense, conceptually wacky material that allowed them to stretch their creative muscles in ways that would eventually come to define their work.

Even after Claremont’s departure, X-Men continued to ooze style into every book around it, bringing things like hyper-violence, manga-inspired art and “realistic” superhero costumes into the mainstream. X-Men’s art was so hot in the early 1990s that it crashed the entire industry. For nearly two decades it was the definition of what it meant for a comic to look “modern” to the average comic book reader. Never the first, but often the first to get popular. Which holds true for the films as well: Blade might have been the first, but it was the 2000 X-Men adaptation that kicked off the pre-MCU era of superhero films and set the black-leather-wink-&-nod “ripped from the headlines” tone that the genre largely hewed to (with the exception of Sam Raimi’s shamelessly cartooney Spider-Man trilogy) until Guardians of the Galaxy blew the top off the whole thing and reminded everyone that colours are good, actually.

And colours are good for X-Men in particular. The series has never been cyberpunk in the strictest sense of the word—by which I mean it has never offered a specific critique of the intersection between capitalism and technology—but the most iconic lineups definitely do feel like the kind of party you’d roll for a Shadowrun campaign. For all Professor Xavier’s moral posturing what they do is still illegal, and it’s a few shades off of your usual cape book vigilante justice too. The X-Men aren’t really concerned with stopping supervillains for the sake of law and order. They’re trying to defend and mediate their own community. They’re not there to fill in where the law is unequipped or underpowered; they fundamentally don’t agree with the laws in place. I think one of the reasons FOX’s ’90s X-Men cartoon has more cultural cache than the more deftly written X-Men: Evolution, and even the movies themselves, is because of how it looks.

The characters are more counter-culture than your average superhero, even vaguely anarchistic. The visual language of cyberpunk is a rejection of the clean science fiction of the ’50s and ’60s. The clash of dark streets and unnatural lights, a society that can’t paper over the rot, a security panopticon that cannot protect its most vulnerable citizens even though there’s endless money for the mechanisms of social oppression. In this sense, it feels right for the X-Men to be wandering around in a neon technocratic hellscape wearing those over-the-top Jim Lee designed outfits. The design becomes a visual metaphor: a world that is crumbling at the edge of a new evolutionary cliff, and heroes who are decked out in apparel that marks them as rebels the same way neons ward you off a poisonous frog. Now that the realistic approach to superheroes has been run into the ground, it’s high time we returned to the era of pink visors, purple pants, and yellow raincoats. Make everything glow.

2. The Morlocks

If you’re not familiar with the finer points of X-canon, the Morlocks are exactly what it says on the tin: a mutant underclass that live in the sewers and who literally named themselves after the monsters from the H.G. Wells novel. Their population generally consists of people with mutations so severe they can’t live in “normal” society due to the stigma. Where the X-Men are vaguely anarchistic, the Morlocks are quite content to give the government and the law the middle finger. Introduced as quasi-villains with a pirate mentality—alienated, bitter, lawless, but fiercely loyal to each other—they’re gradually softened and made into the tragic lynchpin of the first ever “event” in X-Men history.

See: Magneto and the Brotherhood choose to be “bad” terrorists, and the X-Men choose to be “good” terrorists, and the Hellfire Club choose to be maniacal Secret Society deviants who run a combination high school/sex dungeon I guess, but the Morlocks don’t get to choose how anyone reacts to them.

Buy the Book

The Monster of Elendhaven

The draw in modernizing a group of hyper-marginalized mutants who can’t hide their powers being driven to live on the edges of society should be obvious. Even the best of the X-Men movies have tended to pose the whole “Mutant Metaphor” as a… let’s say “middle class” problem, ignoring basic, mundane practicalities like “what if you can’t get an apartment because the landlord is freaked out by how you look”. Let’s take that a step further: what if you couldn’t get an apartment before you developed an uncontrollable mutation that makes you a target of hatred? What if your problems don’t begin and end at the part where you happen to be a mutant? But being a mutant makes it all unimaginably worse. X2 played softball with this question in its interpretation of Nightcrawler, but there are benefits to making it a more explicit, wide-reaching problem. The Morlocks take the Metaphor to one of its two logical conclusions: instead of inheriting the Earth, mutants could be marginalized and hunted down until they’re extinct.

Which is exactly what happens in 1986’s Mutant Massacre storyline, wherein a group of professional assassins are hired to gun down the Morlocks to the very last child, simply for the crime of being unsightly—and they almost succeed too. This storyline represents a serious turning point in Claremont’s run; a loss of innocence that the team never quite recovers from. After this, they’re driven into exile, forced to face down Aparthied and virtual genocide, consumed by inner demons. They abandon all pretenses of being a superhero team for a while, and eventually dive into a magical mirror that runs them through a roulette of possible fates and spits them out into brand new lives.

The villain here isn’t the assassins, or even the force behind the assassins (which turns out to be about as convoluted as anything else in X-Men): it’s the fact that this population was so vulnerable to begin with. It’s the fact that no one cares except the X-Men, and they were too late. This sense of the fragility of the mutant world outside Xavier’s bubble is horrifying when taken to its extremes, but crucial to heart of the franchise.

3. The Death of Cypher

Whew, things were getting pretty dark there for a minute. Didn’t this used to be a series about teen superheroes going to school?

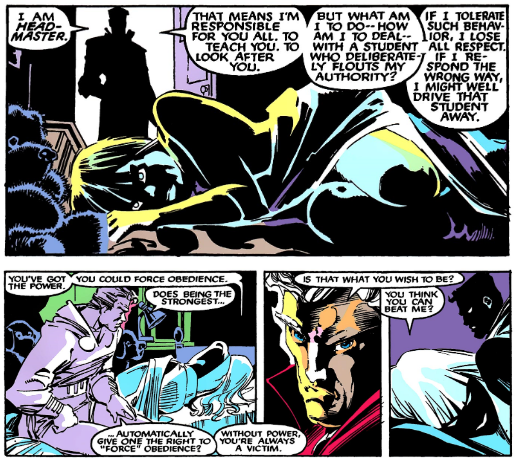

That’s where New Mutants comes in. The second on-going book in the X-line, New Mutants was both a revival of the original Silver Age “superhero school” conception of X-Men and a conscious departure in style. The series went through several major shifts in its 100 issue run, from playing the “X-Babies” joke straight, to emerging as one of the most artistically and atmospherically daring books in Marvel’s arsenal under the pen of Bill Sienkiewicz, to claiming the dubious honour of being the comic where Rob Liefeld became Rob Liefeld.

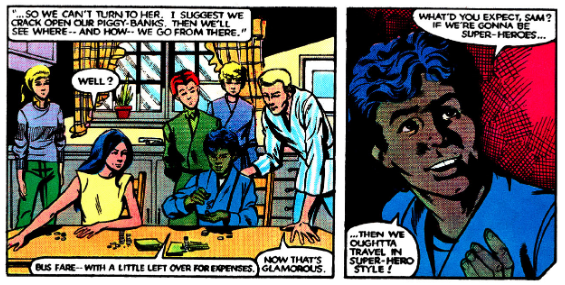

It remained tonally distinct from the parent book throughout, however, simply on the strength of Claremont’s character writing. The kids felt real, even when burdened with the occasional silly phonetic accent and reams of melodramatic dialogue. They cracked under the weight of their inexperience, trauma and teen insecurities. They conquered their fears, or their own immaturity, to emerge heroic. They spent a lot of time wandering around hostile, psychic landscapes as a literal metaphor for all of that teenage mess. They didn’t have access to the X-Men’s supersonic jet, so they took the bus to fight the Hellfire Club.

This focus on low-key, internal conflict is probably why New Mutants is often remembered as having a more significant horror bent than it actually does: Danielle Moonstar is stalked by the demon who killed her parents, Illyana Rasputin is the master of the hell dimension she was kidnapped to as a small child, Xi’an Coy Manh—who in her first appearance killed and absorbed the consciousness of her evil twin brother—spends months as the unwilling host of the Shadow King, a callous psychic parasite who abuses not just her mutant powers, but her body. The sweetest member of the team is an alien virus from a species of malevolent planet-eaters. The characters are not overburdened with their angst, but every single one of them has the most brutally depressing backstory you’ve ever heard. Except, of course, for Douglas Ramsey aka Cypher.

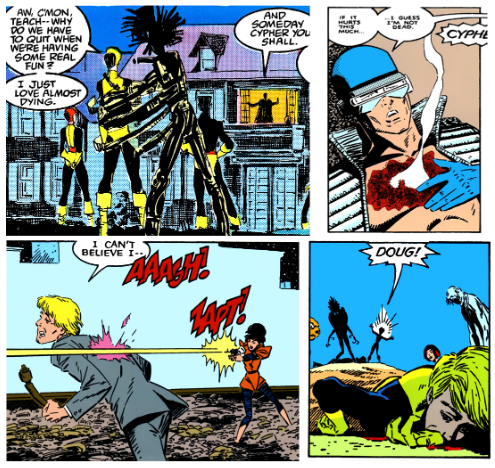

Doug is introduced as Kitty Pryde’s hacker buddy/sort-of-boyfriend; the “normal” guy she hangs out with as a reprieve from her life as a teen superhero. He turns out to be a mutant with the rather innocuous power to innately understand any language and takes to “superheroing” with a surprising amount of zeal for a kid with the same battle efficacy as google translate. Unfortunately, comics aren’t kind to characters with powers with no martial application. As the story goes, fans and artists alike complained that the character was stifling from a storytelling perspective, and so he had to go.

The truth of this narrative is still up in the air, since negative fan response is a somewhat self-selecting phenomenon and Doug’s friendship with the New Mutants’s adopted alien friend Warlock remains one of the most fondly remembered staples of the original run, so readers can’t have hated him that much. But his death feels inevitable in retrospect. Doug isn’t even allowed in the Danger Room, yet his friends don’t think twice about taking him into the literal line of fire. Of course this was a painful, abject lesson waiting to happen.

The story in which Doug dies isn’t particularly good (in fact, it’s a serious contender for second or third worst New Mutants storyline of all time), but the death itself is both brutal and beautifully handled by writer Louise Simonson. It forced the team to seriously consider their spiritual beliefs, it teaches Warlock about the finality of human death, and it’s an important part of what re-radicalizes Magneto, who had been getting pretty cozy as Professor X’s substitute Headmaster. It also highlights one of the ethical dilemmas posed by the conceit of Xavier’s Academy offering mandatory extracurriculars that involve moonlighting as a paramilitary organization.

Most adaptations grapple with this by leaning into the “school” angle without ever questioning the paramilitary aspect. When you think about it for ten seconds, the issue here isn’t: “what happens when one of the kids on your plucky teen superhero team doesn’t have either offensive or defensive powers”. The issue is that Xavier has a team of plucky teen superheroes in the first place. I’m vaguely intrigued that director Josh Boone’s instinct with regards to adapting New Mutants was to take the gothic undertones present in many of the classic stories and run with them, however I think turning it into a straightforward haunted house story already misses the mark on a conceptual level.

The perceived “darkness” of New Mutants doesn’t arise from a lack of literal choice on their part. It arises from the fact that they took Xavier’s hand willingly, with blind trust, and in return they became the “lost generation” of the X-Men line. The arc of the series—no matter how accidentally it got there—begins with the characters arriving at a boarding school, and ends up with them becoming outlaw extremists in the pages of X-Force. Xavier abandons them to Magneto’s care, Magneto abandons them to the tutelage of Cable, Cable abandons them multiple times because he was very busy being in all the big, dumb crossover of the 1990s.

When people decry that “dumbness”—that is, the cartoonish, X-treme bombast; big muscles, big guns, thin stories of comics in the ’90s—what they’re actually complaining about are simplified answers to old questions. Claremont tried to engage with the morality of the X-Men’s extra-legal actions from all angles. The Image Comics generation of superstar writer-artists—like Liefeld, Lee, and Whilce Portacio—lost patience with the moral posturing and just turned them into commandos. Neither actually inverted or properly examined Xavier’s suggestion that being born a mutant imbues one with the responsibility to fight. The New Mutants absolutely “chose” to stay where they were once put there, but they did so in a narrative that never seriously wondered if Xavier was correct to present that choice in the first place. They live in a world so hostile to them that the Professor is always right, even when he’s wrong.

Doug is the obvious counterpoint to the narrative presence of the Morlocks—the “middle class” treatment that the original X-Men movies skirted around. It’s critical to address the question of mutants who can’t hide their powers, but what about people with powers so subtle they’re literally invisible? Not “invisible, until they use them”, but so lowkey that they themselves might never be able to tell that they’re a mutant?

In a world where there are killer robots who can.

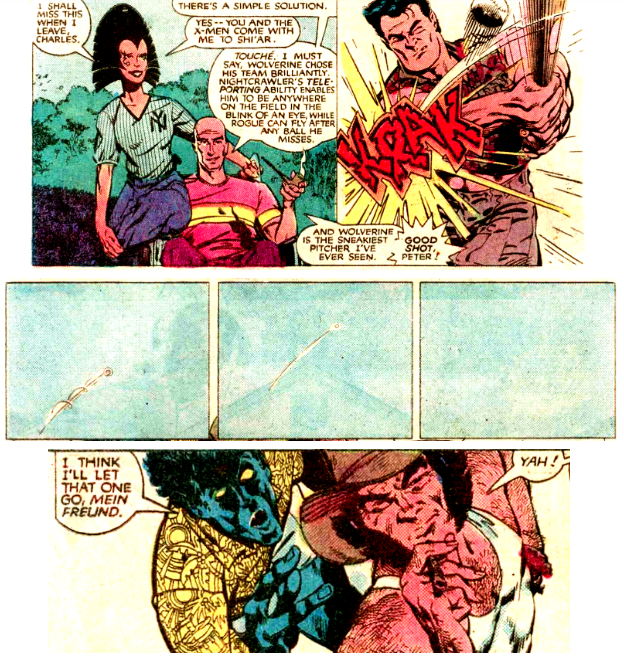

4. The X-Men Play Baseball

Okay, but for real, I know I’m making old school comics sound like a total drag here, but one of the most enduring legacies of Claremont-era X-Men are the frequent, and charmingly dorky, interludes where the teams play baseball (and, naturally, use their powers to flagrantly disrespect the spirit of the game). This is quintessential series lore and frankly I’m offended we never got to see Hugh Jackman swing a baseball bat really, really hard while everyone else got distracted by his glistening muscles rippling beneath all that majestic chest hair or whatever.

I mean, the novelty potential here is off the charts. Avengers: Age of Ultron seriously bombed in terms of public opinion, but it kept the entire MCU fandom satiated for years on a single three minute scene of the Avengers having a sleepover. Imagine fueling an entire franchise on that same energy.

Well, fine—it doesn’t have to be baseball specifically. The X-Men had other hobbies. Kitty went to the arcade and maxed out all the top scores, the New Mutants marathoned Magnum P.I.. Nightcrawler had a steady girlfriend, and Storm was good friends with Kitty’s dance instructor. The Rasputin siblings are forever chopping firewood, because I think that’s what Chris Claremont genuinely believed Siberian farmers did for fun during the U.S.S.R. years. The X-Men had a favourite bar, contacts outside the mutant community and creative interests that didn’t involve superheroics. Claremont set aside whole issues to show Kitty crafting a bedtime story for Colossus’s little sister, or to have Wolverine drag Colossus out drinking in order to kick his ass after he subsequently broke Kitty’s heart. X-Men gets a lot of flack for being “soapy”, but at its best, it’s one of the all-time greatest found family narratives.

And X-Men is at its best when it is firmly situated in a living, breathing universe full of decidedly non-superpowered concerns. There are good stories to be mined from the drama of mutant isolation and extinction (Johnathan Hickman appears to be telling one right now, actually, as a jumping off point for his run in the excellent House/Powers of X series) but the tagline of X-Men is “protecting a world that fears and hates them.” Xavier’s dream is ultimately one of integration and peaceful co-existence, and when the series loses sight of that dream unintentionally, it loses a little bit of its soul.

5. But Also: There Are Some Things in X-Men That Aren’t The Mutant Metaphor

Claremont’s era was also peppered with stories about black magic, demons and operatic space politics. Sandwiched between serious tales of government overreach and anti-mutant hate crimes were lighthearted one-offs starring Kitty Pryde’s pet dragon Lockheed, and sprawling sagas about the X-Men facing their mortality after being infected by bargain bin Xenomorph knock-offs. The book crossed over with more frequently with Thor than it did Marvel’s more grounded fare like The Avengers or Spiderman.

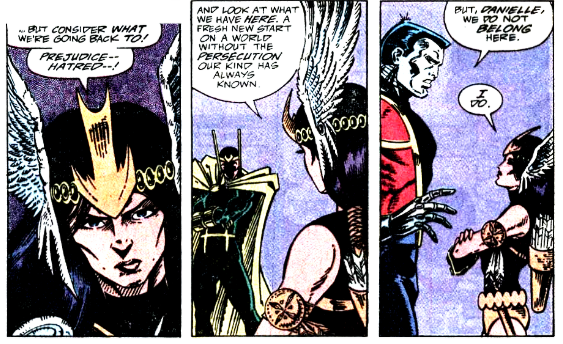

The threads that bind the X-Men to the magical realm today are fairly perfunctory, self-referential to the book’s history rather than truly inspired, but in the ’80s this felt extremely organic. The X-Men were outsiders—of course they got along better with dwarves and aliens than they did with, y’know, Iron Man. It is very easy to lose faith in Xavier’s dream in such a hostile world. What makes the X-Men heroes is that they never stop fighting for that vision of a better future. What makes them relatable is that they’re often tempted to give up. Sometimes, in the case of New Mutant Danielle Moonstar, they’re even tempted to leave the human world behind entirely.

The X-Men films have both flourished and suffered in varying degrees from the initial decision to ground them firmly in present day reality (and when that stopped bearing fruit, situate them in the realm of American nostalgia), but the decision to focus on the perceived “importance” of the Mutant Metaphor and jettison the “silly stuff” wholesale hamstringed the franchise in unnecessary ways considering that characters like Storm, Nightcrawler, Jean Grey, and even Cyclops (did you know that his dad is a space pirate?) have long had one foot stuck firmly in the fantastical. The grim, political stuff gets very one-note after a while; ironically, the ridiculous magic and aliens plotlines might have been an important part of what made the characters feel so rounded, as it gave Claremont a chance to put pressure on personal issues that didn’t relate directly to mutant (or superhero) identity.

This is a needle the MCU is still having a hard time threading. Thor: Ragnarok is probably the first time these two sides of Marvel lore have conversed comfortably with each other on-screen, and it proves that it’s possible to tell a moving—and even subversive—story using the full range of genre fluidity available in superhero comics. Classic X-Men is rich with these stories.

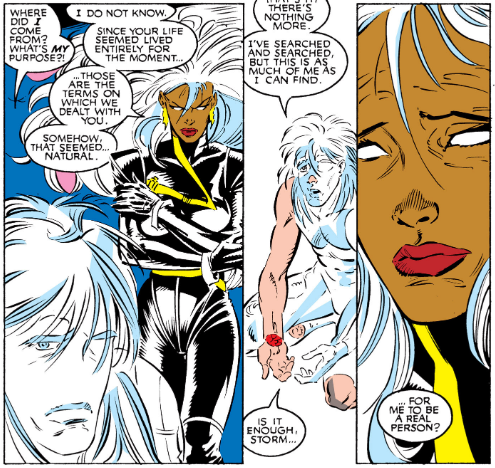

My favourite example of this is probably the fallout from Claremont’s second X-universe miniseries, Magik: Storm and Illyana, the heart-warming story of Colossus’s angelic six year old sister getting kidnapped by a demonic overlord and groomed into becoming his corrupted vessel—the sacrifice through which he will eventually conquer Earth. Naturally, she breaks free of his influence and defeats him, goes home into the loving arms of the X-Men, albeit seven years older than they remember her, etc. etc. The catch is that she doesn’t actually escape “Limbo”; she survives by wresting control of her prison from her jailer and becoming its new Master. She must always balance the use of her demonic powers against the seeds of “evil” her old teacher planted inside her.

Of course, this is all an allegory for child abuse, and a fairly powerful one. Illyana is a strong character—confident, combative, a little bit playful, always masking her trauma behind a vexing demeanor and keeping her friends at arms-length. But scratch the surface and it’s clear her bravado is born from a painful well of self hate, with Belasco’s “evil” serving as a very literal metaphor for PTSD: a thing she blames herself for, that wasn’t her fault. Illyana forces herself to become the morally grey member of her team because she believes that she’s already ruined, so it’s no problem if she takes on the “hard jobs” no one else wants to do.

Illyana’s method of coping with abuse has nothing to do with her status as a mutant—which is almost incidental—or with the political infrastructure of the series, but it is still highly conversant with the overarching themes of trauma and personal responsibility in X-Men. This is perhaps best illustrated by her early relationship with Magneto, the character most defined by his connection to the Mutant Metaphor. He’s not the first person who makes an effort to understand her, but he’s the first who succeeds, because he is also someone who has viewed himself as uniquely equipped to get his hands dirty specifically because of unprocessed hurt. Seeing someone as young and objectively blameless as Illyana toe the line of villainy helps us better understand how Magneto got there himself.

Shying away from the more high concept aspects of X-Men wouldn’t be a problem if the films didn’t keep trying to adapt things like Apocalypse or The Dark Phoenix Saga. These stories are not remarkable for their own sake, they depend on the source material’s cozy relationship with the supernatural and the weird. Dark Phoenix especially suffers in this area, because the original arc is a character driven space opera/tragic romance with absolutely no political subtext. It wasn’t afraid to be cheesy, romantic, and so epic that it spanned literal galaxies. It’s an arc fundamentally at odds with the “gritty”, “modern” approach, which is how a story originally about Jean Grey’s capacity for self-sacrifice and the power of her and Cyclops’s adolescent infatuation maturing into genuine love became—the first time around—a story about how sad it makes Wolverine to kill the woman he had a crush on, and then—second time around—a story about Xavier’s saviour complex.

I mean, maybe we could find a more “realistic” angle from which to tackle the famous story if any adaptation took interest in Jean Grey as a character rather than as a cultural artefact, but the refusal to indulge in the silly and the sublime is a definite hurdle.

6. Mojoworld

Speaking of the silly and the sublime, I want to make a case that Mojoworld is the great, untapped resource of the X-Universe. Not in the sense that there haven’t been enough Mojoworld stories (there have; too many in the last few years, actually), but in that no one’s really milked Ann Nocenti’s original thesis about what unchecked media oversaturation can do to societies. I know for a fact this was her thesis, because there’s this one really weird issue of New Mutants that she literally dedicated to Noam Chomsky and Marshall McLuhan, which is like, wow—I wish I had the bravery to be that direct.

Mojoworld (or “Mojoverse”, or “The Wildways”) is an extra-dimensional plane ruled by psychopathic entertainment executives who operate a brutal caste system based on the premise of unchecked reality television. Here, the lower class slaves exist solely to fight and die on screen for the appeasement of the mass consumers. The peerless Jay and Miles of the podcast/youtube/blog Jay & Miles X-Plain the X-Men once described it as “2000 A.D. meets Looney Tunes”; the denizens of Mojoworld measure their lives in “seasons” and “sequels”. No one ever dies—you just get cancelled. Or mindwiped, and thrown back into the meat grinder for a good ol’ reboot. Citizens are bombarded with nonstop stimulus—live-broadcasts, reruns and advertisements screeching in never-ending competition—and they love it.

So yeah, this is all very Topical and Relevant and everything. Mojoverse is a concept that was born in the ’80s, and then never updated to grapple with the new paradigm of entertainment monopolies, 24 hour news cycles, on-demand streaming, and total media saturation it speculatively poked holes in. Modern Mojo stories tend to stray into the safe territory of rote satire—oh, ha ha, isn’t it funny seeing our favourite X-Men characters in a parody of The Bachelor or Muppet Babies? Which, yeah, that is pretty funny, actually, but it eschews the best thing about Mojoworld, which is that it is absolutely freaking terrifying.

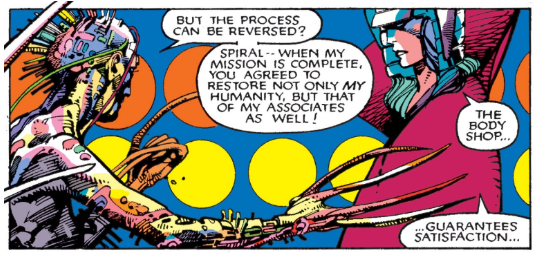

Mojoworld’s premise isn’t simply satirical, it represents a society on the far end of the devolution posited in Baudrillard’s Simulation and Simulacra. I know it’s unbearably pretentious to bring up critical theory in an article about comic books, so I’ll oversimplify: at the beginning, you have art in which symbols are direct representations of reality. At the end, you have art in which the symbols only reflect other symbols, reflecting other symbols, which reflect other symbols, with no throughline back to reality. A reference pit with no bottom, in which the foundation is entirely artificial. Mojoworld is introduced to the Marvel universe through the character Longshot, a former superstar in Mojo’s broadcasts who has had his memories erased and personality rebooted so many times he can’t even conceive of himself as a person.

Longshot was not originally conceived as an X-Men character, and his stint on the team in the late ’80s has more to do with Claremont’s friendship with his creator, Ann Nocenti (who was X-Editor at the time) than any intentional attempt to wind the conceptual cores of the Longshot mini-series with X-Men proper. But Mojoworld fit there nonetheless, tucked right into its little corner of X-Lore as if it were always meant to be there.

The first crossovers between Mojoworld and the X-verse comes courtesy of a character named Spiral, and her “Body Shoppe”. Spiral is the temporal custodian of the Mojoverse; speak her name and she will appear, like Bloody Mary. The ruling class of Mojoworld are spineless aliens who use magic and technology to warp their bodies into monstrous expressions of their media-twisted imaginations. Spiral offers this service to anyone who asks, often with an invisible price tag attached. Wolverine’s ex-lover Yuriko begs Spiral to put her through a grotesque parody of the same process that gave Logan his adamantium skeleton and signature claws.

This element of monkey’s paw transhumanism has fascinating implications in a world where people are born with superpowers. Yuriko also appears in X2, sans her backstory and her memories, presented as a victim of the same government program that created Wolverine. There’s potential poetry in fleshing out this concept—Wolverine’s past coming back to wound someone he loves because of their desperation to “catch up” to him—but it’s limited to the realm of a single question: “what bad things can the government do?”.

There are even bigger questions to be asked in a story about radical human evolution, ones that push at the borders of materialist themes and challenge the philosophical and existential foundations of “humanity”. Yuriko being forced to appeal to a higher power in order to bridge the “gap” between her and Logan admits that the gap is there in the first place. Writer Grant Morrison toyed with this idea endlessly in his 1999-2004 run by suggesting mutant birth rates will outpace humanity faster than anyone could have possibly imagined. His run wondered what happens after the world stops fearing and hating them. I’m still not sure I agree with the conclusions it reached, but it’s arguably the only subversive thing anyone’s tried to do with X-Men since Claremont left the book.

In the same way that Daredevil is naturally equipped to handle the horrors inherent in retributive violence, and Fantastic Four can easily dabble in Saturday morning cartoon tier cosmic horror, X-Men is very adept at evoking the abstract horrors of bodily and personal integrity. “Mutate” is not a word we generally have positive connotations with, despite mutation being a largely benign natural process. And I think that horror element is a big part of the franchise appeal.

X-Men is edgy. It’s—within the confines of whatever the comic standards of the time are—a little bit scary. The goofy ’90s cartoon opens with the audience insert nearly getting nuked by giant robots while hanging out at the mall. The franchise’s most recognizable character has blades on his hands. Wolverine’s potential for violence has lost all innocence to a comic audience that’s seen the excess of Ultimatum and Kyle & Yost’s run on X-Force, but before the gloves came off regarding gore, there was something thrilling and taboo about the coy implication of his brutality. He’s there on a lunchbox, in bright, primary colours with his claws popped out. What do you think he does with them? (The thing he’s best at of course. And it’s not very nice.)

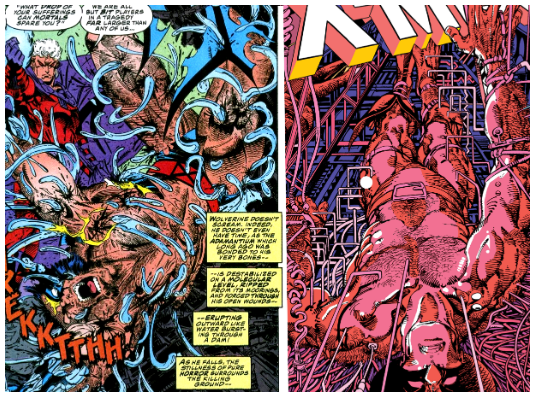

I mean, I definitely found X-Men a little spooky as a kid, in an attractively lurid way, like I was looking at something I wasn’t supposed to. I was endlessly fascinated by that page in Fatal Attractions where Magneto rips out Wolverine’s adamantium—an event often cited as one of the great examples of ridiculous ’90s excess, but which invokes imagery descended directly from Claremont’s collaborations with Barry Windsor Smith in the 1980s.

It’s no wonder this book was outselling dreary old Captain America and the forever antiquated Fantastic Four. It’s also no wonder it started to lose its appeal once the violence became explicit, rather than skin-crawlingly suggestive. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that FOX found a new angle for X-Men after Apocalypse bombed by graduating the series to the realm of an R rating. That might be a way forward. But is it the only way?

The thing about comics is that the genre lines are so fluid that basically anything can be made to fit if you write it the right way, but I believe that there’s a deeper reason the Mojoverse ended up feeling so naturally synchronistic with X-Men. What turned Mojoworld into a hellscape was this: a hundred years of American television, transmitted back in time and through dimensions, so loud and ceaseless that it drove the inhabitants of The Wildways insane. Mojoworld is a physical manifestation of all the cruel, ugly undertones in pop culture—cartoon violence made literal. X-Men has a similar allegorical power: all the chaos and colour of the superhero comic, but with bitingly real stakes. And who else but Marvel’s eternally downtrodden outsiders could possibly challenge the evils of a warped media?

7. Actually, Let’s Talk About the Mutant Metaphor

X-Men is not just “edgy” because of its cyberpunk and horror elements, or because its history of pushing the boundaries of the comic code’s guidelines on violence. For a long time it was the most inclusive book in superhero comics. It might still claim this honour, on a technicality, in 2019. The line boasts the majority of Marvel’s LGBT characters, many of its most complex female characters, and—in spite of turning into the “Scott and Logan” show for the last decade and change—it remains self-consciously international and multi-ethnic in perspective when introducing new characters. It has always tried to tell stories outside the margins of the “mainstream”. Which isn’t to say that this element of the series has always (or ever) been handled well. Claremont’s run in particular is the textbook definition of: “A for effort, but hoo boy did this NOT age well” on basically every metric.

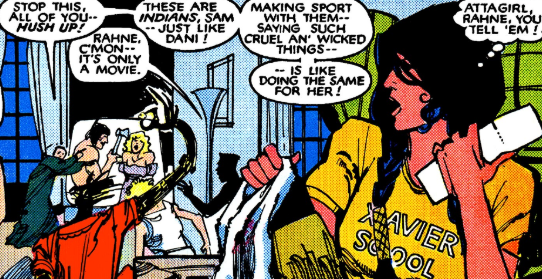

Still, I think that modern iterations of X-Men can take a hint from Claremont’s effort to have a diverse cast; not just racially diverse, but diverse along lines of class, gender and—although it was all relegated to subtext—sexuality, and from his effort to highlight these perspectives. Classic X-Men is told from the POV of characters like Kitty Pryde, Dani Moonstar, and Jubilee (Jewish, Cheyenne, and second generation Chinese respectively). Storm was team leader for over half Claremont’s run. These characters had their experiences of being a mutant informed by their other axis of oppression, rather than their status as a mutant replacing it.

Where the movies had “have you ever tried NOT being a mutant”, the comics were explicit about the oppression its characters experienced outside the confines of mutanthood. The “metaphor” doesn’t have to be all consuming. When it is, it disconcertingly implies that having superpowers is a direct 1-to-1 allegory for being an ethnic, gender, or sexual minority in the real world, which is ridiculous because there are some mutants who could end the world if they wanted to. This is a shallow well from which to draw water. The bottom is defined by what you’re not saying.

This is something the comics themselves lost sight of in the ’90s, chasing profit by over-exposing the most popular characters rather than centering the narrative in the places where it would have the most dividends. The movies wrote themselves into the same hole by doggedly pursuing stories about Wolverine and Charles Xavier even if they had nothing new to say about them. As I implied above: the films often failed to ask questions bigger than “what if the government does bad stuff?” and “terrorism or diplomacy?”.

Classic X-Men had a slightly more subtle debate at its core, one about what tactics are permissible for the oppressed to use in order to defend and liberate themselves, and under which circumstances do the range of acceptable tactics expand? And—can you ever go back once you’ve violated a tenet you once believed to be taboo, even if it’s in self defense? Even if it’s in the defense of someone else? These ideas were not always expressed elegantly, but when the framework is up and running, the subtext almost writes itself. Xavier’s a cautious idealist. Magneto’s a defensive isolationist. The Hellfire Club wield the mechanisms of official power strategically. The Morlocks opt out of the social order all together. Claremont’s run redeemed every one of its mutant extremists and forced all of its heroes to violate their deepest held beliefs, blurring the lines of morality until they bled. The real “villain” of X-Men has always been hate. There was a basic understanding that the violence of the oppressed and the violence of the privileged does not have equal power.

In order for characters like Magneto, Emma Frost and Mystique to “have some valid points,” the social and literal violence inflicted upon mutants needs to be visceral and harrowing. But it’s gauche to approach real life atrocities in a spandex and cape book. It can feel exploitative. That’s why you have Genosha instead of South Africa, the Morlocks instead of the literal homeless population of New York. But you still need to be explicit with how these things intersect with the real world, which is why you have characters like Danielle Moonstar, who asserts her Cheyenne heritage over her mutant identity, and like Magneto, who brandishes his experiences in Auschwitz as a grim warning, because making mutants the only oppression that exists in the world is gauche too.

8. Yeah, This Wasn’t Actually a Listicle, I Tricked You

You could probably already tell that by the length of this article—and the fact that I went zero to sixty on the overblown analysis less than two items in—that I’m not actually trying to promote storylines I think Disney should immediately jump on here.

If I were offering serious suggestions about what I thought would look great on screen, this list would cover significantly more light-hearted topics, like “Spiderverse-style New Mutants movie” or “playfully noir Netflix adaptation of ” or “literal for real Dazzler album that I can listen to on Spotify” or “to hell with it, just find a way to do Excalibur and you’ll have crowd-pleasing stories to pad the entire damn fiscal year until the end of time”. Every X-Men fan could fill their own listicle of Perfect Movies they’ve relentlessly workshopped in their brains over the past few years (incidentally, all of which I would love to hear about in the comments), but I find many of my dream scenarios run up against the same issue.

X-Men as a franchise presents unique adaptational challenges, with its sprawling cast and tangled continuity that has been—I think we can politely say—stuffed self-referentially up its own backside for over two decades now. There’s complicated comic bullshit, and then there’s trying to explain Cable’s actual backstory to someone who has only ever watched superhero movies. Cable was cute in Deadpool 2, I guess, but can you really say he’s a fully successful adaptation of the character in the same way, say, MCU Tony Stark is, without all the pathos conferred onto him by the ridiculous web of largely unintentional retcons that eventually pinned him as Scott Summers’s time-displaced son? Readers saw that baby get born, get kidnapped by demons, get swept away to the future, come back to babysit a bunch of radicool brats with terrible fashion sense, and form a relationship with his now much younger father in real time, which is why we care so much about him eventually becoming a dad himself in the first place. This is the kind of stuff that’s not just impossible to depict in filmic form; it’s also a really, really bad idea to do so.

Many beloved pillars of the series are about exactly this esoteric, which is what happens when you have a single writer dance a series virtually unfettered through nearly seventeen years of constant and “iconic” change, followed by decades of editorial mandates to keep walking circles back to a status quo that never really existed. This problem is why FOX’s X-Men films smartly jettisoned everything but the core concepts: the dream, the school, the metaphor. And yet, of those thirteen films, only a handful of them truly work. Why they don’t work was what I was hoping to get at the heart of here: what are the core themes of X-Men? What was it about Claremont’s run (under the peerless editorial vision of Lousie Simonson and Ann Nocenti) that made it exceptional? And why has the series struggled to escape the gravity of an era that flamed out in 1992?

9. Well?

I think the franchise works best on the premise of: something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue (and gold). By which I mean: X-Men became the bleeding edge of American comics by merging a sense of real history with constant forward momentum, rarely trail-blazing but always keeping its thumb on the pulse of the contemporary culture.

The movies thus far have see-sawed between reverent and iconoclastic in ways that don’t always make sense, like straight up doing Days of Future Past with Wolverine because he’s popular, without considering what Claremont was doing when he chose to tell the story through the eyes of Kitty Pryde—the youngest, greenest and most down-to-earth member of the X-Men. There’s nothing shocking about seeing grizzled, cynical Wolverine continue to be grizzled and cynical in a dark future. Iconic characters like Cyclops, Storm, and Jean Grey are given no personality beyond “they’re supposed to be here because it’s X-Men”. I think most comic book fans can agree that these empty references are categorically worse than no reference at all. Remember Deadpool, with no mouth?

A solution to this franchise fatigue might be as simple as fumbling around at the edges of the toolbox for the weirder instruments, rather than just hammering away at the same old nails. Logan and the Deadpool movies appeared to grasp at the edges of this ethos, which is why Dark Phoenix was such a disappointing note to go out on. What does The Dark Phoenix Saga even mean in 2019? It’s symptomatic of the same problems that have plagued the comics for decades: malingering away in the annals of iconography without asking what the fundamental values of the series really were. A reference to a reference to a reference that doesn’t remember what it was originally referencing.

10. The Beginning

Claremont’s X-Men was resonant because it was in conversation with the politics and culture of the time. The first X-Men film only half succeeded because it thought the politics of Claremont’s X-Men were no longer relevant but didn’t have enough new ideas to replace them, and so it stumbled to reinvent itself alongside the rapidly changing zeitgeist of the 21st century. You can definitely accuse me of reading too much into things here, but I think the beauty of superhero comics is their ability to straddle the divide between art and pulp in ways that cheeky, self-aware “trash” cinema can only dream of, and X-Men has always excelled at putting a splash of neon paint on the ugliest topics out there without diminishing their gravity. What are the base elements that comprise a “good” X-Men story, no matter the character, the setting, the genre? Protest, oppression, responsibility, family, trauma, identity, horror, and hope for a better world against all evidence that it exists.

If we’re going to start over again, at the beginning, let’s throw out the usual questions of the superhero story and instead ask the broader questions of speculative fiction.

What did the mutant metaphor mean in 1977?

What are the implications of a mutant school in 2020?

What will Xavier’s dream be in 2024?

Personally, I’d be excited to find out.

Jennifer Giesbrecht is a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia where she earned an undergraduate degree in History, spent her formative years as a professional street performer, and developed a deep and reverent respect for the ocean. She currently works as a game writer for What Pumpkin Studios. In 2013 she attended the Clarion West Writers Workshop. Her work has appeared in Nightmare Magazine, XIII: ‘Stories of Resurrection’, Apex, and Imaginarium: The Best of Canadian Speculative Fiction. She lives in a quaint, historic neighbourhood with two of her best friends and five cats. The Monster of Elendhaven is her first book.

Jennifer Giesbrecht is a native of Halifax, Nova Scotia where she earned an undergraduate degree in History, spent her formative years as a professional street performer, and developed a deep and reverent respect for the ocean. She currently works as a game writer for What Pumpkin Studios. In 2013 she attended the Clarion West Writers Workshop. Her work has appeared in Nightmare Magazine, XIII: ‘Stories of Resurrection’, Apex, and Imaginarium: The Best of Canadian Speculative Fiction. She lives in a quaint, historic neighbourhood with two of her best friends and five cats. The Monster of Elendhaven is her first book.