In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week’s installment explores the appearances of the name “Finduilas” and tracks how Tolkien’s use of this name becomes symbolic, consigning the women who bear it to the grave as markers of another’s failures and successes.

Tolkien was no stranger to the art of recycling character names. For the most part, these characters have little to nothing in common beyond their shared monikers; rather, it seems that the linguist in the dear Professor just couldn’t bear to let a good compound go to waste. Every so often we see traces of one character in another (like the Legolas Greenleaf of Gondolin and the Legolas of the Fellowship); at other times, though these are fewer and further between, Tolkien makes an effort to adjust the timeline to allow the reused names to refer back to the same character (as in the case of Glorfindel). It’s rare, though, that either of these things happens to important or unique names. There may be multiple and varied Denethors, but there’s only one Gandalf, one Frodo. Though Aragorn’s name is repeated, that repetition is important symbolically: his genealogy is a significant part of his claim to the throne and his ability to command the respect and loyalty of his followers.

What, then, do we do with recycled names that are not only unique and significant, but that also seem to carry with them specific character traits and connotations?

This is in fact the case with Finduilas, a name that becomes attached to four distinct women in the legendarium—but while these characters are largely unconnected, they share specific characteristics and face similar fates. In fact, the name tends to emerge from the shadows in stories of a very specific tone, dealing with very specific themes, which suggests to me that the name itself conjured up a certain aura of sadness and despair for Tolkien. I first noticed the pattern while writing my previous piece on Denethor, Steward of Gondor: a good place to start.

One interesting thing to note right away is that Finduilas, princess of Dol Amroth, mother of Faramir and Boromir and wife of Denethor, wasn’t immediately named Finduilas. Tolkien first called her Emmeril, and then Rothinel, before finally settling on Finduilas (Sauron Defeated, hereafter SD, 54-5). Unfortunately, we know very little about this woman apart from her familial connections. She was the daughter of Prince Adrahil of Dol Amroth and married Denethor in 2976. It was likely a political alliance; Denethor was 46 at the time, Finduilas only 26. She was one of two elder sisters of Prince Imrahil, who makes a memorable appearance in The Lord of the Rings. Legolas notices that he is related, if distantly, to the Elven-folk of Amroth (872); and the prince is also something of a healer (864). He readily and joyously accepts Aragorn as his liege-lord (880), and later, Lothíriel his daughter will marry Éomer of Rohan. In the main text of The Lord of the Rings, however, Finduilas is mentioned only once by name, and then by the narrator: Faramir gives to Éowyn a mantle that belonged to his mother. At this point we learned that she “died untimely” and that Faramir understands the robe to be “raiment fitting for the beauty and sadness of Éowyn” (961).

What sadness troubled Finduilas of Amroth? It’s unfortunately unclear, but it’s possible to make a few educated guesses. Unfinished Tales suggests that Denethor’s “grimness” was a source of disquiet for Finduilas. We can easily imagine, from a brief mental comparison of her husband, the Steward, and her brother, the Prince, that Finduilas might have found life in Gondor difficult. Denethor, though he loved his wife (Unfinished Tales, hereafter UT, 431), was a man bearing a great burden, one for which he was ultimately insufficient in mind and spirit if not in body, and we see the toll that was taken quite clearly in the lives and burdens of his sons. Doubtless Finduilas knew this. I think it’s telling, in this context, that she’s introduced in The Lord of the Rings with the name of her former home: she is Finduilas of Amroth, associated still with her life before her marriage, as if she clung to that anchor through the sorrows of her short adulthood. Furthermore, Tolkien writes that Denethor likely began using the palantir before the death of Finduilas—and that troubled her, and “increased her unhappiness, to the hastening of her death” (431). She “died untimely” (a phrase of which Tolkien is fond) and of a cause unknown to us in 2987 (The Peoples of Middle-earth, hereafter PM, 206), when Faramir was but four years old. His memory of her eventually became “but a memory of loveliness in far days and of his first grief” (LotR 961). It seems that however dim that remembrance was, her sorrow made an impression on him as a defining feature, thus explaining his gift of her robe to the suffering Éowyn.

But Finduilas of Amroth wasn’t the first to bear the name, nor was she the first to be marked by grief. In fact, it only bears the symbolic weight it does because others claimed the name before her. Another of these women was, perhaps surprisingly, Arwen Undómiel of Rivendell. Before she was Arwen she was Finduilas—and the change was made, abruptly, because Tolkien decided that the name better suited the princess of Amroth. Arwen’s life as Finduilas is relatively uneventful; she plays a remarkably minor role in the published Lord of the Rings, but her influence was even less developed in earlier drafts. The name Arwen Undómiel emerged in draft B of “Many Partings,” incidentally at the same moment as Tolkien conceives of her gift to Frodo (the Evenstar and, perhaps, passage on a West-bound ship).

But Arwen only became Finduilas because someone else was before—her grandmother, Galadriel. For a very brief span of time, the woman who would later become the Lady of Lórien bore the name of these other women in the text.

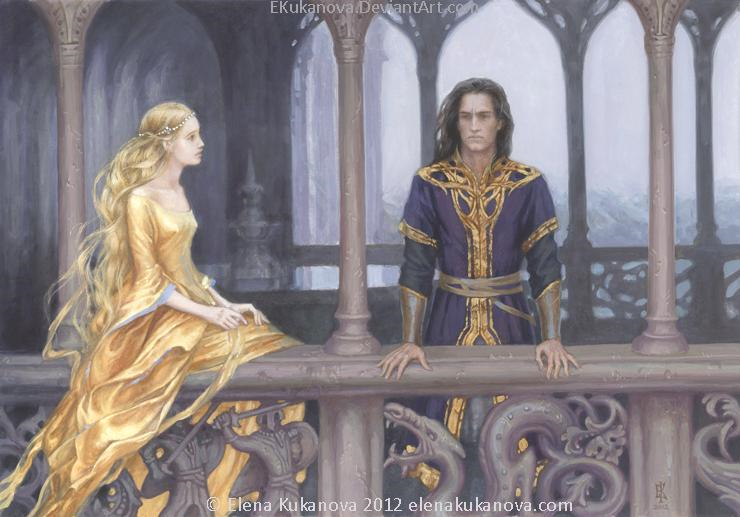

The first Finduilas hailed from Nargothrond and is largely known because of her unfortunate association with the hapless Túrin, who forsakes her during the sack of Nargothrond, resulting in her capture and death. But even she was not “Finduilas” from the first. Tolkien originally called her Failivrin, a name which remained hers but, as with many of Tolkien’s women, became a sort of nickname given to her by a lover. Perhaps predictably, we know very little about this Finduilas. She was always, even from the beginning, the daughter of the king of Nargothrond (first called Galweg, then Orodreth). Though the names are sometimes different in the early drafts, her story exists in what is almost its final form early on in Tolkien’s writing process. Here are the major plot points: Finduilas of Nargothrond was engaged to or in love with a man by the name of Flinding/Gwindor. He’s captured and tortured in Angband, but eventually, is making his way back home when he falls into company with Túrin, who at this point is wandering, self-exiled from Doriath. They become fast friends after Gwindor saves Túrin’s life, and together they come to Nargothrond, where they are denied entry because no one recognizes Gwindor. He’s sustained great injury since his captivity in Angband, and he’s grown old untimely, and is also, according to The Grey Annals, “half crippled,” old, and grey (The War of the Jewels, hereafter WJ, 83). This is where Finduilas enters the story. She, alone of all Nargothrond, believes and recognizes her old love, and at her prayers the two wanderers are welcomed into the kingdom.

It turns out to be a less joyful reunion than expected. As Túrin, concealing his true name, grows in influence and power in the kingdom, Finduilas finds her heart turned towards him against her will. Though she still loves—and now pities—Gwindor, he is not the same man who left, having become grim and silent. She fights her inclinations, and keeps them secret. Túrin, meanwhile, is experiencing the same, but out of loyalty to Gwindor keeps silent about his love, though he continues to seek Finduilas out and spend time with her alone. Both Finduilas and Túrin are tortured by this development, as both feel that their love betrays Gwindor, whom they both hold dear. Túrin becomes moody and throws himself into warfare and the defense of Nargothrond; Finduilas, as a woman, is given no outlet for her grief and simply grows strikingly thin, pale, and silent. Now, Gwindor isn’t an idiot. He realizes very quickly what’s happening. Unable to avoid the situation any longer, he confronts Finduilas and, in an effort to persuade her that being with Túrin is a bad idea, betrays his friend by revealing his true name. He then goes to Túrin and attempts to convince him that it’s a doomed romance—but Túrin finds out (in some drafts, through Finduilas; in others, through Gwindor himself) that he has been outed as the cursed and disgraced son of Húrin, and the relationship between the two men implodes.

Then Nargothrond is attacked by Morgoth’s Orc army and the dragon Glaurung. In the course of the battle, Túrin encounters Glaurung, and, characteristically overestimating his own power, looks into the dragon’s eyes, falling under his spell. The battle is lost in this moment, and as Túrin stands, unable to speak or move, Finduilas is dragged away screaming by Orcs. Her cries will haunt Túrin until his death. Glaurung then convinces Túrin that his mother and sister are in danger in Hithlum, and Túrin, believing him, forsakes Finduilas and the other captives in order to find them. He of course discovers that Glaurung was lying, and in bitter remorse seeks Finduilas too late. He comes upon the people of Haleth in the forest and learns that they attempted to save the captives, but failed when the Orcs slew them rather than give them up. Finduilas herself was pinned to a tree by a spear; her dying words asked the woodsmen to tell Túrin where she lay. They bury her there, naming the mound Haudh-en-Elleth.

Later, as is well known, Túrin’s amnesiac sister, Nienor, will be found half-conscious on the mound and Túrin, connecting her because of this with his lost love, falls in love with her and they marry. A final encounter with Glaurung reveals Nienor’s true identity, and the doomed pair individually commit suicide. Tolkien’s intention was to revise the story so that Túrin takes his life over Finduilas’s grave, but this change never made it to paper beyond a few scribbled notes (WJ 160).

Apart from these events, we don’t know much about Finduilas as a person. The Lay of the Children of Húrin describes her as a “fleet maiden” and “a light, a laughter” (LB 76). In a later draft, the epithets “fleet and slender,” “wondrous beauty,” “grown in glory” are added (LB 82). She is also repeatedly referred to as “frail Finduilas,” which is never really explained, nor does it receive much support by the events of her life. Nevertheless, it shows up in all drafts of The Lay of the Children of Húrin, nearly as often as she is mentioned. From Unfinished Tales we know that she “was golden-haired after the manner of the house of Finarfin” (164), a characteristic that caused Túrin to associate her with the memory of his sister Lalaith, who died while yet a child. He tells Finduilas, horribly foreshadowing the future incest, that he wishes he still had a sister as beautiful as she (Unfinished Tales, hereafter UT, 165). There are also some minor suggestions that Finduilas has some power of foresight: in The Lay of the Children of Húrin she intentionally meets and becomes acquainted with Túrin’s sorrows in dreams, where her pity turns to love against her wishes. She also experiences vague misgivings about Túrin’s involvement in warfare in Nargothrond, an impression that turns out to be painfully accurate when it is Túrin’s military overreaching that ultimately causes the kingdom’s fall (UT 166). No one believes her, however (also a common fate for Tolkien’s wise women), and thus all is lost.

Finduilas, then, is a sort of archetype or original pattern. She is a woman whose life is first disrupted by the great Enemy, and then by a man, grim and burdened, who is destined to fall to ruin at the hand and will of the Dark Lord. Her life is marked by sorrow, pain, and then death. Her grave, Haudh-en-Elleth, marks where her physical body lies, but it is also a symbolic reminder of Túrin’s failure and the inevitability of his downfall. I think it’s significant that Tolkien experiments with the name in the cases of Galadriel and Arwen—it suggests that their stories might have been darker and less hopeful than they are. Did Tolkien imagine Aragorn as a revision of Túrin?

Finduilas of Amroth, however, clearly reprises the role of her namesake of Nargothrond. As I pointed out earlier, Denethor is in many ways a reprisal of Túrin: grim, strong, and independent, he is pitted against a foe beyond him, and so dies in despair. The existence of Finduilas of Amroth helps us to recognize this connection, to pity Denethor, and to see her “untimely” death as its own sort of marker: it retroactively explains the impossibility of Denethor’s position as well as recasting Gondor as a sort of Nargothrond. Only this time, the city has a hero who is unmarked by the Dark Lord’s curse. The fact that Denethor couldn’t save his Finduilas—while Aragorn does save his—speaks volumes about the way we’re supposed to understand their narratives. Unfortunately, it also consigns the Finduilases of history to the grave, where they exist as little more than monuments to the failures or successes of the men in their lives. She might bear many different faces, but ultimately, Finduilas is every bit as trapped in her fate as Túrin and Denethor were in theirs.

Megan N. Fontenot is a dedicated Tolkien scholar and fan who loves, almost more than anything else, digging into the many drafts and outlines of Tolkien’s legendarium, but is currently a little bit bitter about the treatment of Finduilas. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 and feel free to request a favorite character in the comments!