Todd: Welcome back, readers. Big shout-out to all those who took the time to leave a comment or suggestion on our last articles, Five Forgotten Swordsmen and Swordswomen of Fantasy and Five Classic Sword-and-Planet Sagas.

Howard: We do everything by fives.

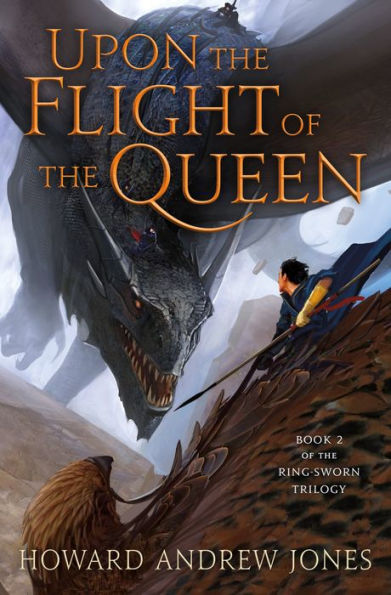

Todd: At least we have a system! Today, in honor of my friend Howard’s brand-new fantasy novel Upon the Flight of the Queen, which arrives in hardcover on November 19, we’re going to try something a little different. Since I have a real live fantasy author up here at the podium with me—and one whose influences are well known—we’re going to take the opportunity to look at some of the greatest fantasists of all time, and the different ways each of them teach us to write fantasy.

And we’ll draw some practical examples from Howard’s work. Howard, how does that sound to you?

Howard: Sounds like I’m going to be doing most of the work this time.

Todd: Works for me. Ready? Get comfortable.

Howard: Yeah, ready.

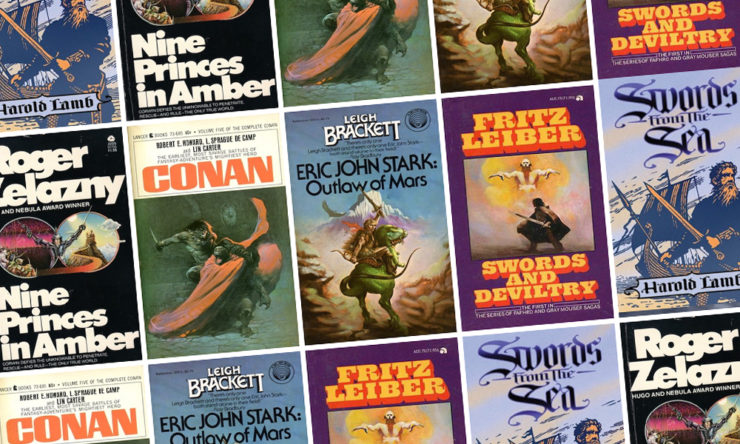

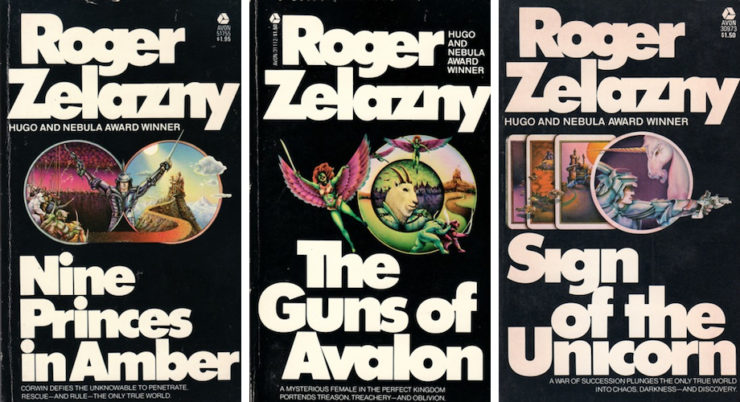

Todd: Great. Let’s start with an easy one. As long as I’ve known you, you’ve talked about Roger Zelazny as a towering influence on your work, and I think it’s easy to see why. Can you tell us just what elements you see in his fiction that really speak to you, and how you’ve put those lessons to work in your own fiction?

Howard: From a steady diet of science fiction, I moved suddenly into fantasy at the age of ten or twelve and fell straight into The Chronicles of Amber.

Todd: You’ve described it as a gateway.

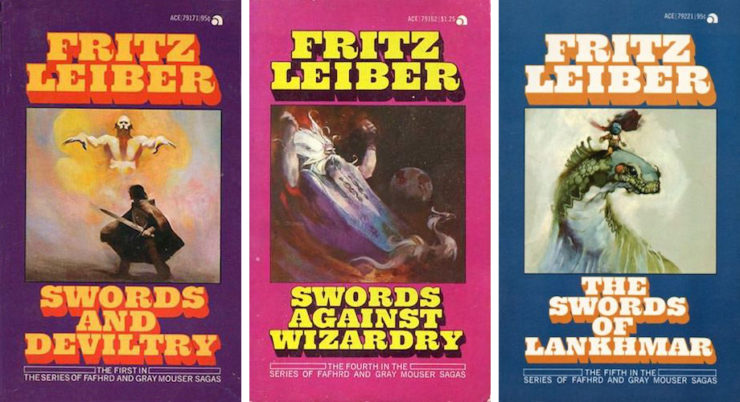

Howard: Exactly, this, and Leiber’s Swords Against Death (still my favorite Lankhmar collection) were a splendid way to see some of the best that fantasy fiction had to offer in the mid-to-late ’70s. Both happened to be in the local used bookstore, and I found them when I headed there with a list I jotted down from the famed Appendix N, at the back of the original Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Todd: We’ll get to Leiber later. What was special about Amber?

Howard: With Amber I found a world, or series of worlds, that was always a little more than it seemed. It starts out on our Earth, in a hospital, where our hero wakes up bereft of memory.

Todd: A scene you once told me Zelazny had stolen from Raymond Chandler.

Howard: Hah! Yes. Steal from the best, right? Once I finally got around to Chandler, something I regret taking so long about, I discovered that the opening of Nine Princes had an awful lot to do with a middle section in Farewell, My Lovely.

Todd: But you digress.

Howard: I blame you. Anyway, from that mundane start, we soon realize that Earth is just one of many shadows of one true reality, and Corwin is a prince of that realm, Amber. Later on (avoid this next part, if you don’t want spoilers…) we discover that there are even more layers—another one true place, for instance, with enemies and ancestors that Corwin had no knowledge of, and a reality that’s even more “true” than Amber. Throughout the saga there’s grand worldbuilding and lots of intriguing characters with hidden agendas and specialized powers.

The deeper Zelazny leads us into the setting, the more secrets he unveils. He never really infodumps until you’re at the point where you are begging for more information, like a good hardboiled mystery writer. He gives you just enough information to let you know what’s going on, and leaves you with questions about how and why things are. Questions are gradually answered through context or, finally, by Corwin himself after both you and he have been curious about them for a long time.

Todd: That’s something I wished a lot more writers understood.

Howard: Every fantasy writer has things they want readers to know, things they think are important to move the narrative forward, and the urge to spill it all can sometimes be overwhelming. But doing that before the reader gives a damn is a rookie mistake.

Todd: Modern readers can sniff an infodump a mile away.

Howard: Exactly. A big part of what Zelazny taught me is the art of backstory is exactly that—an art. You think you need to explain that big lump of backstory before the action can really get going? You don’t.

Buy the Book

Upon the Flight of the Queen

Hold back, as long as you can. Every time you think you need to clarify something, drop a crumb instead. Keep your readers guessing. Don’t just explain; made them curious first. And even then, don’t give them everything. Don’t give up the final answers until they beg for them. When you finally drop the final pieces into place, there should be an audible click in your reader’s brain.

If more writers understood the art of backstory the way Zelazny did, the world would be a better place.

Todd: In his Tor.com review of For the Killing of Kings, the first novel in the series, Paul Weimer picks up on some of Zelazny’s influences in your work. See what you think:

The touchstone in this particular instance is Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber… The Amberian aspects of Jones’ novel come to the fore in the geography and worldbuilding…. In the shifting lands, reality becomes malleable, and a storm can change reality around the travelers at a moment’s notice. Only someone trying to escape dire pursuit or seeking someone or something lost in such lands would be crazy enough to pass through the Shifting Lands. Given the plot of the novel, this turns out to be an excellent idea. The characters’ passage into this changeable landscape does evoke the idea of shadowshifting or hellriding in the Amber Chronicles rather well….

The Amber chronicles are all about the fractious and colorful, literally larger than life Amber royal family—does Jones’ novel stand up on that score?… Kyrkenall, taciturn and with a reputation as a loner drawn into the situation against his will, has some of the brooding Corwin in him. Personally, thinking of The Three Musketeers, connected him more to the brooding Athos.

Howard: Paul knows his Amber! I think the parallels are dead on. Honestly, I always wanted to read more stories featuring Corwin and Benedict because I love those characters. And when I first conceived Kyrkenall and his pals—some twenty-five years ago, believe it or not—my inspiration was a lot more apparent than it is even now. After kicking around in my head for so long, through numerous story concepts, they’ve taken on their own identities. As for hellriding, shadow shifting and all that, wow, what an awesome idea that was. I wish I’d thought of it…

Todd: You once likened Zelazny’s plot reveals as onion peeling, except that there were wonders and new mysteries with each new layer. I could tell you were paying attention to that concept in the first book in your new series, For the Killing of Kings. For the first two-thirds of that book, I was propelled along by the compelling mystery surrounding the fate of N’lahr’s sword, and just what the Queen was up to. You maintained the mystery for 300 pages, and delivered a wonderfully satisfying surprise twist at the end. How have you followed Zelazny’s dictum on keeping the readers in the dark in the second book?

Howard: Throughout Amber, Zelazny had masterful twists and surprises, although none can really compare with the end of book 4, The Hand of Oberon, which literally made me dive across the bed, where I was reading, to grab the final book to find out what happened next. No book conclusion, ever, in all my years of reading, has worked so well, and it’s a high water mark I’ve yet to hit myself.

But it’s something I certainly keep in mind as I build a story. Keep your readers interested and wanting more. With Upon the Flight of the Queen I worked hard to implement the lessons we’ve discussed. Zelazny continues to surprise as Amber rolls along because there were always a few more secrets to be learned, both about character motivation and about how the world actually worked. Information you thought was accurate proves either to be more complicated, or to have been completely wrong. In my own books, there are definitely more secrets to learn, and as some mysteries are solved, other related mysteries are introduced.

Todd: In his obituary for Roger Zelazny, George R.R. Martin talks about his love of music, and the unpublished musical comedy Zelazny was working on before his death. I’ve noticed that you blend music and fantasy in much the same way. You wrote music as part of creating Upon the Flight of the Queen, for example.

Howard: I usually write a theme song for my characters, and I often sit down to play it on piano before I start writing for the day.

Todd: How long have we known each other, and you’ve never mentioned this?

Howard: It’s not the kind of thing that comes up in idle conversation, is it? The Ring-Sworn Theme was just a small part of a much bigger project. My son Darian is an animator, and the character designs and cultural aesthetics he started playing around with after he read Upon the Flight of the Queen really captured what I was looking for. One thing led to another, and soon Darian had created a complete book trailer. It needed a theme, and I co-wrote one with Darian. He did the arrangement himself.

Todd: You’re being modest. I doubt it was as easy as you make it sound! In fact, I thought Darian did a bang-up job with the whole project, and the music really stands out. Readers, check it out here and then tell Howard he needs to release an album of theme music.

Next, I want to ask you about a writer whom you’ve studied for decades. When we talk about writing, you bring her up a lot. And I mean, A LOT.

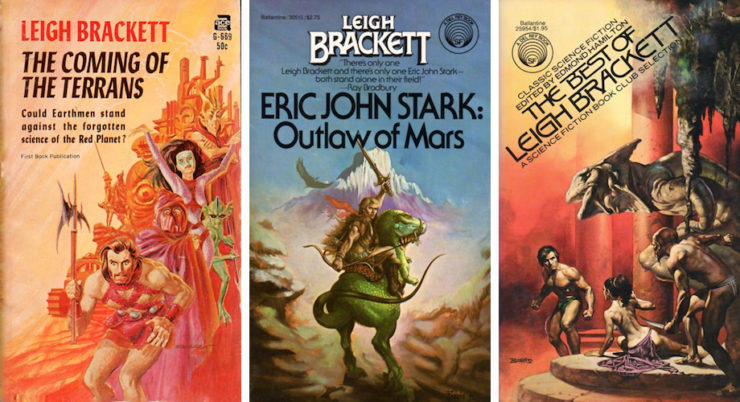

Howard: This has to be Leigh Brackett.

Todd: We had lunch in Chicago last week, and when we talked briefly about broccoli, you quoted Brackett three times.

Howard: She’s one of my very favorites.

Todd: I’ll say. Tell us why.

Howard: She conjures wonderful places full of loss and longing and characters full of need. She and Zelazny are similar in the way that they can create splendid scenes that stick in your imagination. Brackett’s characters are bruised and battered by life but have kept on going. They don’t whine about their problems. They come with deep backstories, but finding what’s really motivating them is part of why you keep reading. It’s not all laid out for you there in front in a prologue or something.

Look, I dig Burroughs, as you know, and it might be that Brackett’s own dying Mars wouldn’t exist without his, because he was a huge influence upon her (not to mention scads of other people). But I like Brackett’s Mars and Brackett’s Venus better. I’ve tried to describe the fading, gorgeous beauty of her Mars and her Martian cultures, but it really can only be experienced firsthand. Reading Brackett is like drinking down the autumn of a really grand year that you’re never going to see again.

Todd: A little like Ray Bradbury’s Mars?

Howard: Quite a lot like it, but with far more swashbuckling. I love Ray Bradbury’s work, but I don’t turn to it for adventure. Brackett had a wonderful, vivid imagination, lots of forward momentum, and characters who acted rather than being acted upon. And her writing was fluid and often lyrical. I go back to all of my favorite writers and re-read passages, but she’s one whose work I revisit every year. There’s no one quite like her.

Todd: What have you learned from her that you put into practice?

Howard: I’ve tried to incorporate the lessons I learned from Brackett into everything I write. From Zelazny I took all kinds of inspiration for deep worldbuilding and the reveal of mysteries. From Leigh Brackett I can only aspire to create the grandeur of her scene-setting and the creation of her flawed and haunted characters. Keep in mind that a lot of my favorite writers excel at weird world-building, and while I certainly admire her for that as well, it’s her skill with atmosphere that I try always to remember.

Todd: More than once you’ve said it was Zelazny and Leiber who blew the doors off of your imagination. We’ve already talked about Zelazny, so—

Howard: So, Fritz Leiber?

Todd: Right.

Howard: It’s true that Leiber and Zelazny were the first heroic fiction/sword-and-sorcery writers that I found, and that they changed my fiction interests forever. Before them I was pretty much a science fiction guy. And after Leiber, like so many others, as a young writer I tried again and again to write stories of a daring twain of urban fantasy heroes. So yes, I was influenced by Leiber, but I don’t think that he’s shaped my own style as much as some of these others, in part because his own style is so particular. That said, I love the witty banter and the swordplay and the imagination, and I think some of the Lankhmar tales are among the finest sword-and-sorcery tales ever set to paper—and then of course Leiber even coined the term “sword-and-sorcery.” So he’s important to me. But if you’re going to choose my strongest influences, I don’t think he’s as important as the two preceding, or Harold Lamb.

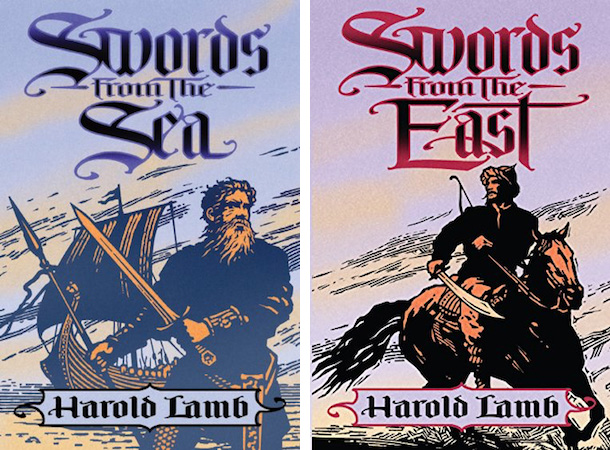

Todd: I knew we’d get here eventually.

Howard: Of course we would, and you knew I’d cheat, because Lamb really isn’t speculative fiction, although his work cast a long shadow across sword-and-sorcery tales that came after him. He reads an awful lot like a sword-and-sorcery writer. He wrote historical swashbucklers with incredible drive and immersive atmosphere and cycles of adventures. The first thing I noticed about his work—after the obvious, that wow, these are really great adventure stories—is how they felt like the Lankhmar tales in that while each story stood alone, the more you read, the more you learned about the world and the characters, and some adventures even built directly off of their predecessors.

I love that about short serial fiction—I liken it to creating episodes of an older TV series, where each tale had to stand alone. Lamb’s tales are equally enjoyable if you’re only dipping into one randomly, or if you’re reading them in sequence. And of course if you’re reading them in order, they’re even more rewarding.

Todd: Can modern writes learn from Harold Lamb, do you think? Can you point to anything he helped you with, especially in your longer work?

Howard: Oh yes—first of all, they’re great fun to read. And there are all kinds of excellent craft skills to be learned from them. As with Brackett’s work, I try to apply lessons I got from him to everything I do. A lot of his plots arise from having his antagonist and his protagonist desiring two different things that put them at odds. It’s almost as though each is a wind-up toy and he ratchets both of them up, aims them at each other on a table, and then records what happens.

Todd: Right. You get to watch the fireworks, the surprises, and learn about the character strengths and weaknesses as they go.

Howard: He also was an absolute master at giving you just enough to understand the mindset of a different culture or the history without bogging you down with unnecessary detail. You could always sense great depth there behind the “need-to-know” information he revealed to keep the story moving, and that’s something I try to emulate: show us enough of the world so we can understand what the characters are invested in, but don’t bog us down with too much detail. Just because the author knows more doesn’t mean he has to TELL more. Lamb had a wonderful ability to tell us just enough.

Todd: From listening to you for years, I know that Lamb was a huge influence on another writer who you list as a direct influence on your own work, one who IS a fantasy writer.

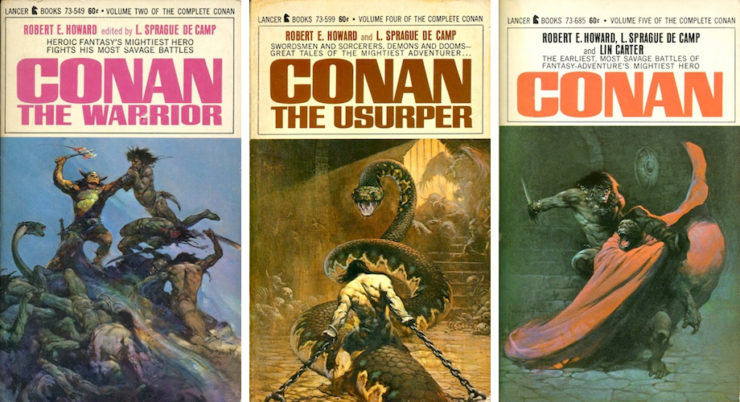

Howard: Robert E. Howard. Exactly. He remains one of my favorites. Being a lot better known, his name gets used in marketing more than any of these other writers. I remember some people claiming that my Dabir and Asim novels were like Robert E. Howard adventures, and then others being disappointed because they weren’t that at all.

Todd: They read more like the Arabian Nights to me.

Howard: Yes. I’d say this new series has a lot more to do with Amber than it does Robert E. Howard, so I’m glad no one, this time, seems to be comparing it to Conan. That said, I’ve read so much Robert E. Howard that his influence can’t help but seep into all of my work. I keep some of his approaches in mind no matter what I’m drafting.

For instance, I can think of no one who surpasses him when it comes to his depiction of battle scenes. His writing is incredibly cinematic and vivid. He wielded that typewriter like a camera, zooming in to give you one guy on a battlefield and then pulling back to show you the bigger situation. With REH in command you always know exactly how the battle is progressing and yet still know where the characters you care about are on that field. He’s so good he made it look easy, and it isn’t.

Todd: What should writers who want to learn from Robert E. Howard pick up on?

Howard: Before I draft a really big battle scene I try always to go back and read a couple of his tales. Not that I try to emulate his style—most who try to sound like him fail horribly, and I long ago gave up in that vein. Instead I try to remember key lessons, such as, while you can certainly snatch some colorful adjectives, utilize strong verbs. Know when to switch from a close-up to a distant shot. Know when it’s important to give blow-by-blow descriptions and when you should summarize.

There’s a lot more to REH than THAT, of course—he’s similar to Brackett (or she to him, as she came later) in that the atmosphere is all important, brooding and somber as it is. Many of his imitators don’t seem to pick up on that, and focus instead on the gore and the sexy women (more a feature of his lesser tales, when he needed a quick buck), forgetting that a lot of his stories feature moral complexity and greater depth than is popularly assumed.

Todd: Thanks a lot for sharing what you’ve learned from some of fantasy’s greatest teachers. Any final thoughts for aspiring writers who are looking to the great writers of the past for inspiration?

Howard: Keep reading! And read with an open mind, remembering the time and place and culture was different for these older writers. Know your genre—one of my first big writing breakthroughs happened after I went back to read the work from the grandfathers and grandmothers of fantasy. Read outside your genre—my second big breakthrough happened after I started reading hardboiled westerns and mysteries of the ‘50s and ‘60s and got a handle on that lean, mean pace and characters who have to be described both quickly and deeply without time for infodumps.

Above all, keep writing. And stay open to the marvelous promise of fantasy that all of these great writers believed in.

Todd: Thank you, Howard.

Howard: My pleasure.

Howard Andrew Jones’ novel Upon the Flight of the Queen, the second book in the Ring-Sworn Trilogy, will be published by St. Martin’s Press in November.

Todd McAulty’s first novel The Robots of Gotham was published by John Joseph Adams Books in June of last year.