In ancient Greece, a hecatomb was a great sacrifice, the offering to the gods of a hundred oxen. It was a demonstration of royal power and wealth, and a means of propitiating notoriously capricious powers.

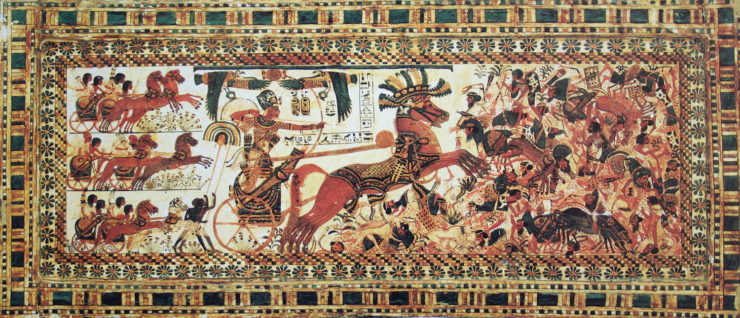

Well before Greeks were slaughtering oxen en masse on divine altars, horse cultures across Europe and Asia and even down into Egypt were burying horses in the graves of royal and noble personages. Often the horses were sacrificed in the funeral rites, as transport and as companions in the otherworld. Sometimes they may have predeceased their owners, as might have happened to the little red mare whose mummy lay in the tomb of Senenmut, the architect and favorite of the female Pharaoh Hatshepsut.

The power of horses over the human heart and imagination is tremendous. It’s more than their size and power, or even their usefulness as transport and as engines of war. There’s just something about who they are as well as what they can do. They connect with humans in ways that no other animal does.

They live just long enough, too, to loom even larger in the conceptual world. A healthy, well cared for horse, barring accident or illness, can live twenty-five to thirty years or more—a few even into their forties and beyond. With a working life that begins on the average somewhere between ages three and five, that’s a long time for an animal-human partnership.

Ancient humans wanted to take their horses into death with them. For status of course, because horses were and are expensive to maintain. But for love, too, I think, because a world without horses isn’t worth going to. If you love your horse, you want to stay together. You want to continue the partnership as Senenmut did, for eternity.

Modern horse people don’t have quite the same options as ancient riders and charioteers. For most, horses are an emotional more than an economic necessity, which means that when the horse’s life ends, it’s a deep shock. It’s also a complex logistical problem.

In the US, many areas actually ban horse burials on private property. That leaves, basically, cremation or handing the body over to a disposal company that may bury it legally (or even compost it), or may deliver it to a rendering plant to be recycled in various forms. Cremation of an animal that weighs upward of a thousand pounds is extremely expensive and requires a facility that can handle a body of that size. Disposal is much less expensive though still not cheap: the cost of picking up the body and taking it away.

Burial itself, if the area allows it, is still rather complicated. Digging a grave by hand is labor-intensive to say the least, between the size of the hole and the weight of the horse. Modern technology, fortunately, offers a solution: excavating equipment that can take care of the job in under an hour. It’s still a matter of finding someone who is willing to do it, or to rent the equipment for it—and in the latter case, knowing how to run the equipment. And getting it, often, on short notice, because while some horses show clear enough signs that the owners can make the appointment days ahead, many take a sudden turn, and a veterinary call for a sick or injured horse ends in euthanasia.

It’s not something anyone wants to think about, but it’s the reality of keeping animals. Life ends, gradually or suddenly. Then there’s what comes after.

I’ve known people who won’t have animals because they can’t face the inevitable outcome. It’s understandable. But for most animal people, and horse people certainly, the time we get with them is worth the knowledge that it ends.

The past month in my horses’ breed has been like a slow-rolling hecatomb of dearly beloved partners. The oldest living Lipizzan, Neapolitano Nima I, died in August at the age of forty. Since then he’s gained a harem of mares, most in their thirties, and one tragically young brother-stallion. For most of them it was their time; they had lived long lives. But it’s never really long enough.

In memoriam: Neapolitano Nima I, Cremona, Mizahalea, Pandora, Carrma, Maestoso Alga.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.