Science fiction is often about discovering new things. Sometimes it is also about loss. Consider, for example, the SF authors of the early space probe era. On the plus side, after years of writing about Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and the other worlds of the Solar System, they would find out what those worlds were really like. On the minus side, all the infinite possibilities would be replaced by a single reality—one that probably wouldn’t be much like the Solar System of the old pulp magazines.

Not that science fiction’s consensus Old Solar System, featuring dying Mars and Martians, or swamp world Venus, was ever plausible. Even in the 1930s, educated speculations about the other planets were not optimistic about the odds that the other worlds were so friendly as to be merely dying. (Don’t believe me? Sample John W. Campbell’s articles from the mid-1930s.)

Science fiction authors simply ignored what science was telling them in pursuit of thrilling stories.

If an author was very, very unlucky, that old Solar System might be swept away before a work depending on an obsolete model made it to print. Perhaps the most famous example was due to radar technology deployed at just the wrong time. When Larry Niven’s first story, “The Coldest Place,” was written, the scientific consensus was that Mercury was tide-locked, one face always facing the sun, and one always facing away. The story relies on this supposed fact. By the time it was published, radar observation had revealed that Mercury actually had a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance. Niven’s story was rendered obsolete before it even saw print.

Space probe schedules are known years in advance. It would be easy to plan around the flyby dates to ensure stories were not undermined as Niven’s was.

Authors did not always bother. Podkayne of Mars, for example, was serialized in Worlds of If from November 1962 to March 1963. In December 1962, Mariner 2 revealed a Venus nothing like Heinlein’s, well before the novel was fully serialized.

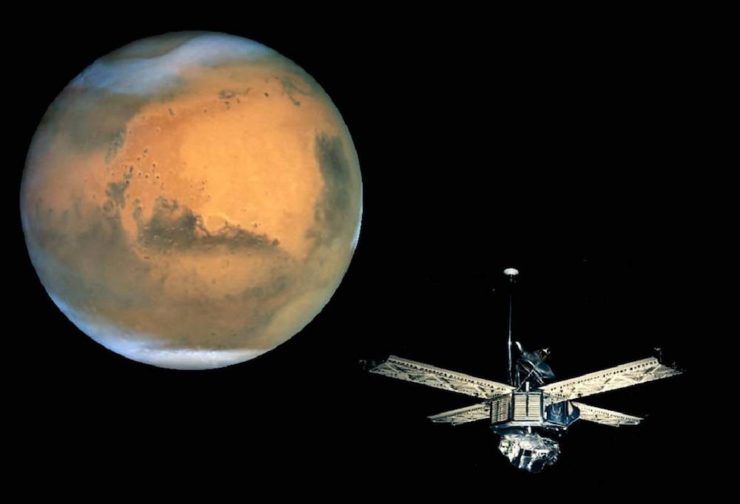

An impending deadline imposed by a probe approaching another world could be inspirational. Roger Zelazny reportedly felt that he could not continue writing stories set on the Mars of the old planetary romances once space probes had revealed Mars as it is. The Soviet Mars 1 failed on route to Mars in March 1963, buying Zelazny a little time, but more probes would no doubt come. Zelazny’s “A Rose for Ecclesiastes,” depicting a fateful encounter between an arrogant Earthman and seemingly doomed Martians, saw print in November 1963. Mariner 4 revealed Mars to the Earth in July 1965. Zelazny’s tale may not be the final pre-Mariner 4 story to see print, but it’s probably the most significant just-barely-pre-Mariner story set on Mars.

At least two sets of editors decided to fast forward through the Kubler-Ross model, zipping past denial, anger, bargaining, and depression straight on to acceptance. Raging against the loss of the Old Solar System won’t make the Old Solar System return. Faced with new information about Venus, Brian Aldiss and Harry Harrison decided to publish 1968’s Farewell, Fantastic Venus, which collected short pieces, essays, and excerpts of longer works that the pair felt comprised the best of the pre-probe tales.

Farewell, Fantastic Venus gave the impression of grognards reluctantly acknowledging change. Frederik and Carol Pohl’s 1973 Jupiter took a more positive tack, celebrating Pioneers 10 and 11 with an assortment of classic SF stories about old Jupiter. I prefer the Pohls’ approach, which may be why I prefer Jupiter to Farewell, Fantastic Venus. Or perhaps it’s just that the stories in Jupiter are superior to those in Farewell, Fantastic Venus. Plus it had that great Berkey cover.

The glorious flood of information from advanced space probes and telescopes does not seem likely to end any time soon, which means there is still time to write stories and edit anthologies powered by the friction between the universe as it is and as we dreamed it might be. Not just in the increasingly wondrous Solar System, but also neighbouring stellar systems about which we know increasingly more. Celebrate the new Alpha Centauri, Tau Ceti, and Barnard’s Star with the best stories of the old.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.