I didn’t get into comics, really, until I was fresh out of college and doing a slew of horrible internships and temp jobs. I was sharing a house with a group of roommates I didn’t really get along with and spending most of my time as a captive audience for various weird flavors of office politics, under the thumb of bosses who ranged from borderline harrassy to just kind of obnoxious. I was determined to write fiction, but I kept writing in circles, and I was groping desperately for the motivation to keep scribbling, rather than just play video games for a few more hours. And then winter came and it dumped a few feet of snow on me, making my commute to the latest depressing nowhere job that much more awful.

And that’s when I really discovered comics, and got lost in their four-color worlds. I started going to some local comic-book stores and just buying up tons of back issues, especially the ones in the quarter bins. I didn’t even care what they were: I bought armfuls of indie experimental comics alongside complete runs of Batman and the Avengers. I read about the Infinity Gauntlet in the same session as Love and Rockets. And that’s when I discovered Vertigo Comics, which was DC Comics’ weird, experimental imprint.

DC just announced they’re pulling the plug on Vertigo after a quarter century, so this is a really good moment to remember just how fantastic this line of comics really was. Vertigo was like the intersection of mainstream superhero comics and weird experimental surrealism, built on a foundation of comics like Alan Moore and John Totleben’s Swamp Thing and Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean’s Sandman. I can’t believe Vertigo is coming to an end—there’ll still be weird-as-fuck comics and bleeding-edge experiments in future, but there won’t be anything quite like Vertigo, from one of the Big Two publishers, anytime soon.

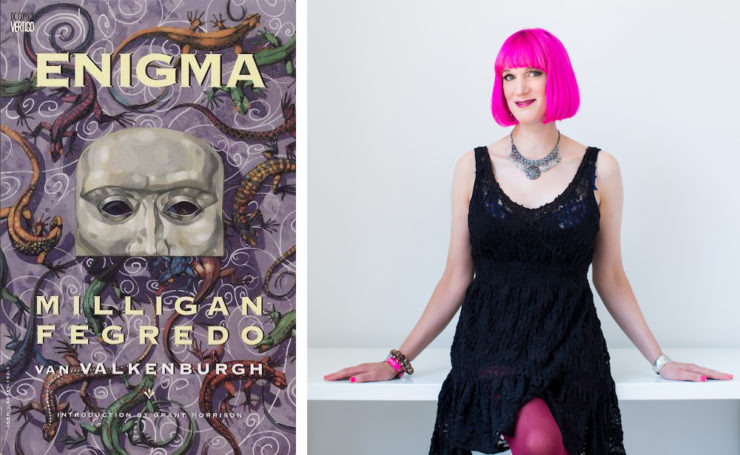

And one of the weirdest comics to come out of Vertigo was Enigma, an eight-issue series by writer Peter Milligan and artist Duncan Fegredo. I found a battered trade paperback of Enigma at the back of a used book store during that godawful winter, and it blew my mind. I still have that collected edition on my shelf, and it’s still one of my favorite comics.

You can read an incredibly detailed, thoughtful analysis of Enigma from Greg Burgas at Comic Book Resources, but basically it’s a story of a dude named Michael who has a boring, overly-regimented life with his girlfriend Sandra. The first hint of Michael and Sandra’s dysfunctional, dead-on-the-vine relationship is when we learn that they always have sex on Tuesdays, like it’s a notch on some chore wheel. But then a comic-book, superhero reality starts invading Michael’s world, starting with a fantastical supervillain/serial killer named the Head, who eats people’s brains.

And then Michael actually meets a comic-book superhero come to life: the opera-masked all-powerful savior named Enigma. And long story short, Michael and Enigma hook up, and Michael realizes that he is gay. (There’s a hint, late in the series, that Michael’s contact with the Enigma mask “turned” him gay, but when Enigma offers to make Michael straight again, Michael declines the offer of heterosexuality.)

This is a story about falling in love with a heroic ideal, and about being transformed as a result, and Michael’s embrace of his own queerness resonated with me on so many levels. Especially since Michael’s discovery of his “new” sexuality goes along with a greater transformation, in which he becomes a stronger, better, more realized person, and it’s hinted that he evolves beyond the limitations of humanity. Michael’s encounters with Enigma help him to become a truer version of himself, and it’s a glorious metaphor for the whole process of realizing that you’re not just the role that society smushed onto you from above.

In retrospect, it is super weird and kind of problematic that Michael doesn’t just discover he’s really queer, but that his sexuality is changed by a magic superhero mask—but when I read this comic, it made perfect sense to me. It felt like this book was speaking directly to me, to the escapist part of my brain that was seeking a way out of a yucky constrained existence through stories about heroes and weirdos.

Enigma told me that the part of me that was struggling to understand my queerness and the part of me that wanted to get lost in colorful strange stories were linked at some deep level, and maybe those two parts should be talking to each other more.

Buy the Book

The City in the Middle of the Night

And it’s hard to believe now, but in the early 1990s when Enigma was published, pointing out the inherent queerness of superhero narratives was still a huge taboo. The X-Men were doing metaphors for homophobia, but we had only just gotten one actual gay member of the X-Men (Northstar, who at at the time was part of the Canadian superhero team Alpha Flight). Green Lantern had a spin-off title called New Guardians, featuring a gay character who was a huge stereotype (whom the supervillain Sinestro tries to seduce, and who later gets AIDS). There was actually a novel, What They Did to Princess Paragon by Robert Rodi, all about the terrifying backlash that would ensue among comic-book nerds if a major superheroine was revealed to be a lesbian.

So this was a long ways before the era of Midnighter and Apollo, or Batwoman, or Nia Nal. Engima came out during an era when superheroes were supposed to liberate us from death traps and evil supervillain lairs, not so much from heteronormativity and restrictive gender norms.

And it doesn’t hurt that Enigma is gorgeous. Duncan Fegredo’s artwork is lush and beautiful, and he famously changes his art style over the course of the story, going from messy and full of lines to clean and strong. So you can actually see Michael becoming a different person, and his whole world transforming, through his contact with Enigma.

When you see the two men in bed together, immediately after sex, it’s a beautiful splash page that’s full of tenderness and sexuality. The narration says, “It wasn’t a smooth operation. A lot of fumbling, dead ends, false starts, but what they lacked in technique they made up for in feeling… These are two men redrawing the maps of themselves.” The sweetness and tenderness in these scenes of same-sex romance left a huge impression on me, especially against the backdrop of the reflexive cynical weirdness of so many other experimental comics at the time.

You can see why Grant Morrison says Enigma is better than Watchmen, DC’s much more famous superhero deconstruction.

Vertigo published a lot of comics that dealt with queer themes, in often-flawed but exciting ways. Morrison’s The Invisibles includes a gender non-conforming character, Milligan and Chris Bachalo’s Shade the Changing Man has a character who can change genders at a whim, and Hellblazer established John Constantine as one of the first openly bisexual characters in mainstream comics. But Enigma still deserves a unique place in Vertigo’s history, because of how beautifully it depicts a same-sex relationship, and a journey of discovery and transformation.

Enigma came along just at the right time to open some doors for me, and nearly 25 years later, it remains potent and transformative. The collected edition is well worth hunting down.

Charlie Jane Anders’ latest novel is The City in the Middle of the Night. She’s also the author of All the Birds in the Sky, which won the Nebula, Crawford and Locus awards, and Choir Boy, which won a Lambda Literary Award. Plus a novella called Rock Manning Goes For Broke and a short story collection called Six Months, Three Days, Five Others. Her short fiction has appeared in Tor.com, Boston Review, Tin House, Conjunctions, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Wired magazine, Slate, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Lightspeed,ZYZZYVA, Catamaran Literary Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and tons of anthologies. Her story “Six Months, Three Days” won a Hugo Award, and her story “Don’t Press Charges And I Won’t Sue” won a Theodore Sturgeon Award. Charlie Jane also organizes the monthly Writers With Drinks reading series, and co-hosts the podcast Our Opinions Are Correct with Annalee Newitz.