Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

This week, we’re reading Tanith Lee’s “Yellow and Red,” first published in the June 1998 issue of Interzone. Spoilers ahead.

“And the things which so many would find intriguing – old letters in bundles, in horrible brown, ornate, indecipherable writing—caskets of incenses and peculiar amulets—such items fill me with aversion.”

Summary

Gordon Martyce has inherited his uncle William’s country house, a valuable property, but his long-time lady friend Lucy is more excited about the windfall than he is. Gordon likes his London job and his London flat, and he’s not at all sure he wants to marry Lucy and let her redecorate the old place. Though the gloomy green-shuttered building would certainly need redecorating.

He makes the train trip down on a drizzly day that dims the September splendor of the countryside. His first impression is that the oaks practically smother the place; inside, whatever light makes it through is dyed “mulberry and spinach” by the stained glass windows. At least the housekeeper, Mrs. Gold, has left fires laid. Yet he, ever stalwart and unromantic, gets the creeps.

Mrs. Gold comes in next morning. Morbidly cheerful, she details all the deaths that have occurred in the house. His uncle William was just the last to succumb to a mysterious malaise. Its first victim was Gordon’s grandfather, a renowned explorer of Eastern tombs. Next went William’s two sons, only fourteen and nineteen, then William’s wife and sister. A “great worry” it was to watch, but oddly enough only Martyces contracted the ailment—the servants of the house remain healthy, herself included.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Gordon had better sell, Mrs. Gold advises. He’s inclined to agree. His inspection reveals far more rooms than he’ll ever want, depressingly old-fashioned and universally damp. Gordon has no interest in the doubtless valuable foreign curios or the ponderous tomes in the library. Give him sensible chairs and a down-to-earth detective novel any day.

That night he—uncharacteristically clumsy—spills whisky on some old family photographs. The liquor leaves splotches on four of them, splotches that soon turn “raw red and sickly yellow.” Of course Gordon knows how random marks can “take on apparently coherent forms.” Nevertheless, he can’t explain why each splotch appears to represent a repulsive creature: frog-faced, horned, with forelegs that end in cat paws and no rear legs at all, just a tail like a slug’s. Two red dots in the “face” resemble eyes.

Gordon meets with house agent Johnson to discuss the planned sale. Johnson remarks that Gordon might want to drop in on vicar Dale in the neighboring village, who can tell him more about his uncle. Gordon’s more interested in whether Johnson’s ever heard of alcohol burning photos—no, not unless we’re talking bathtub moonshine.

So Gordon experiments. He soaks one of the splotched photos and three new ones in whisky, sure either nothing will happen or the photos will be defaced entire. The splotched one remains the same, marked only with the yellow and red creature. The others take on a single mark, again shaped like the creature. The first shows William’s sons playing on the lawn; the creature lies coiled among nearby trees, cat-like, watching. The second shows William with wife and sister; the creature lies at their feet “like some awful pet.” The third shows William and his younger son; neither looks unhappy, though the son should be screaming, for the creature has crawled up his leg, gripping with tail and forelegs.

Gordon’s had enough of his inheritance. He walks to the village to catch the evening train home. While he waits, he drops in on Reverend Dale. Their conversation turns to the house’s unhealthy effects on the Martyces. Dale says he doesn’t believe in ghosts, but influences are perhaps another matter. Gordon’s grandfather once asked the previous vicar about a belief some cultures have about photographs stealing their subjects’ souls. What his grandfather actually wondered was whether a camera might “snare… something else. Something not human or corporeal. Some sort of spirit.”

Gordon catches the train home. In his journal he writes, “Thank God I have got away. Thank God. Thank God.”

Next comes a letter from Lucy Wright to a friend. She’s upset over Gordon’s death, which she can’t understand. He never confided in her about his trip to the old manse. But, “old stick-in-the-mud” though he normally was, Gordon suddenly wanted to go out with her every night. Lucy hoped he was getting ready to propose, especially after he made a big deal out of her birthday. Their dinner out ended badly, though. She showed Gordon her new camera, and the restaurant manager insisted on taking their picture together—though Gordon grew angry, even frightened. Later Gordon called to say he was picking up her “maiden” roll of photos. Next thing she heard was from the police: Gordon had thrown himself under a train.

Oh, Lucy is so glad to hear from her kind friend. You see, she went around to Gordon’s flat after the funeral. On a table she found her photos, stuck to a newspaper, smelling of whisky. Most look fine. The one of her and Gordon in the restaurant? Lucy knows she’ll sound crazy, but—there’s a red and yellowish mark on the photo that looks like a “snake thing with hands—and a face.” It sits on Gordon’s shoulder, “with its tail coming down his collar, and its arm-things round his throat, and its face pressed close to his, as if it loved him and would never let go.”

What’s Cyclopean: Lee draws not only on Lovecraftian language, with the eldritch wind at the windows, but on her own vivid descriptions: The mulberry-and-spinach light of the stained glass windows is a very particular sort of mood-setter.

Another linguistic delight is Mrs. Gold, of whom the narrator notes: “Not only did she employ words that she could not, probably, spell, but… she was also able to invent them.” Gordon’s uncle had “never a day’s indisposition” before he moved into the house, and Mrs. Gold herself has been healthy every day except for during her “parturition.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Women are generally unreliable, asserts our narrator. And clumsy (he says as he knocks over his whiskey). So weird that he’s not married yet.

Mythos Making: Is that Tsathoggua climbing your leg, or are you just happy to see me? (If it’s not Tsathoggua, it’s certainly an equally disturbing contribution to the literature of batrachianalia.)

Libronomicon: Shakespeare points out that it is quite common for people to die. Shakespeare fails to mention that it’s particularly common among Narrator’s relatives.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Narrator tries to resist his impression of a beast in the photographs coming—nearer. “That way madness lies.” He certainly doesn’t want to become some “querulous neurasthenic fool” like so many of the people who saw more action than him in the war.

Anne’s Commentary

We’ve talked before about the color yellow, that sunny daffodilly hue, epitome of cheerfulness, except in association with a certain King and wallpaper. Red’s another color with positive associations—the brilliance of a rose, the sexiness of a ballgown, the solemnity of religious vestments. Yellow and red together? Flowers can rock it, dragons and phoenixes too. Otherwise I find it a tad garish.

And, at times. terrifying. Think of the cross-section of a severed limb, rim of fat around shredded muscle. The ooze of pus, the splatter of blood, stained bandages, jaundice and hemorrhage. Immediately Tanith Lee lets us know her colors won’t be pleasant. Or rather, she lets us know with elegant misdirection. The story’s first yellows and reds are of autumn foliage, how nice. But drizzle quickly fades them, and our next yellow is “sickly,” our next red “raw,” livery of the Martyce scourge.

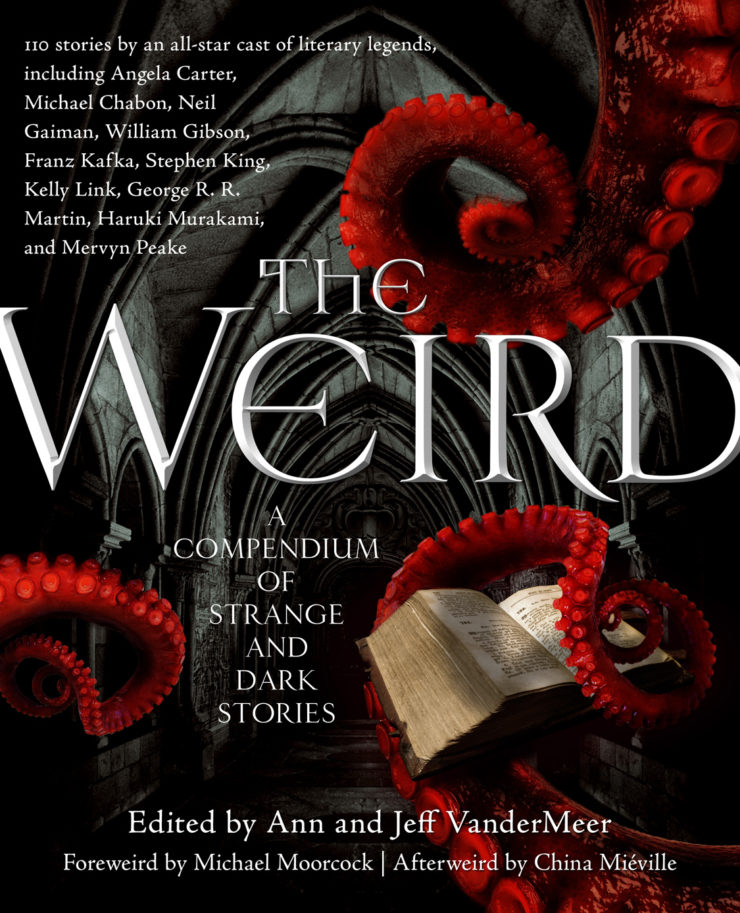

In their introduction to “Yellow and Red,” The Weird editors Ann and Jeff VanderMeer sense Lee “riffing off of” M. R. James’s “Casting the Runes.” I hear many other echoes of James, who loved the trope of the unwanted familiar. In addition to the horror of “Runes,” James conjured a whistle-summoned and sheet-embodied haunt (“Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”), a face-sucking companion-monster (“Count Magnus”), a hanged witch’s spidery assassins (“The Ash Tree”), a homoarachnid vengeance-demon (“Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook”), a batrachian hoard-ward (“The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”) and a terribly clinging ghost (“Martin’s Close”). On a different tack, there’s “The Mezzotint,” in which a picture shows things that shouldn’t be there.

Not to let James get all the shout-outs, anything slug-like must bring to mind his contemporary, E. F. Benson. And what about Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Green Tea” and its monkey-familiar?

“Yellow and Red’s” most “Lovecraftian” theme, though, isn’t the unwanted familiar discussed above. It’s the inheritance problem. Inherited property, inherited genes, both can be inherited curses. Lee implies that Gordon’s grandfather violated a tomb whose resident spirit followed him home. Evidently Grandfather Martyce spotted his tormentor in photos he took of the tomb and later exposed to a revelatory solvent. Probably he used the artifacts and books Gordon sniffed at to rid himself of the creature. The creature stayed put. Maybe it meant to punish Grandfather. Or maybe, as Lee hints, it pursued him out of a weird twist on attachment or love. It’s frequently compared to a pet, specifically a cat. It appears at first at some distance from its objects, comes closer until it lies at their feet, creeps up their legs, hugs their necks in a forever grip. Clearly the creature drains its objects of vitality, creating the appearance of a wasting disease. Less certain is whether it does so out of malice or necessity, intentionally or unwittingly.

Whatever its motive, the creature fixes on Martyces, attacking no one else. It’s accustomed to tough prey, like Grandfather and William and even William’s long-languishing sister. Gordon must be a disappointment to it. He believes he’s made of stern stuff, but how has he been tested? He missed serious action in the War. He’s been coasting along in a comfortable job, a comfortable flat, a comfortably undemanding relationship. He has a comfortable fortune. What he doesn’t have is, well, much interest in anything outside his comfortably circumscribed life. Even Lucy admits he’s a bit of a bore. A decent fellow, but stodgy. Reading, I wanted to yell: Will you please describe a few of those ARTIFACTS? Will you note down a few TITLES from Grandfather’s shelves? Will you read some of those old LETTERS?

I mean, this guy is the opposite of a Lovecraft narrator. Put one of Howard’s people in the Martyce house, and he’d pore over grotesque statuettes, brown-edged missives and tomes until we had the whole story of Grandfather’s adventures and the Martyce malaise. If he had to climb onto the roof to get a clear look at the weather vane in the shape of an Oriental deity, he’d be up there faster than Alex Honnold. Only then, seeing that the vane was the slug-tailed image of the beastie, would he allow himself to go insane? Gordon Martyce has no curiosity. Zip. No capacity at all for terror and wonder, just animal fear and narrow self-interest. Plus he’s so steeped in misogyny and bigotry he’d certainly bridle if you called him on them—he’s no misogynist or bigot, he’s simply stating the facts about women and those uneducated savages.

Talk about an unsympathetic character, but damn if his sheer density doesn’t make him an interesting narrator after all. He keeps the story lean, focused on the whisky-altered photos; and he leaves the Martyce mystery mysterious, a provocation to our imaginations. I feel kind of bad that he dies, but I feel worse for the creature, so abruptly deprived of its sustenance.

I wonder if Lucy’s long tenure as Gordon’s girlfriend would qualify her as a Martyce. She strikes me as someone who could appreciate a loving pet, something (unlike Gordon) to never let her go.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

When you open your favorite pulp magazine, or an anthology labeled The Weird, you expect weirdness. The author can play into this—or can play against it, building up an ordinary world against which the eventual weirdness will shine all the darker. “Yellow and Red” goes the latter route, starting us with the perfect house for a haunting, and a new owner who has no appreciation whatsoever for its mood-setting trappings. Old-fashioned curtains the color of oxblood? Dreary. Shelves full of curios from the Far East and Egypt? Meh. Grand rooms lit by crackling fireplaces? The heating cost is surely prohibitive; better sell the thing and get back to the familiar roar of traffic in the city.

No standard Lovecraftian house-heir, this Gordon. You could hardly pick someone less romantic—he boasts of it—and less inclined to ill-fated studies driven by irresistible logic and the old attraction-repulsion trap. Give this guy a copy of the Necronomicon, and he’d sniff about the unsanitary state of the not-exactly-leather binding and the repetitive dullness of Alhazred’s prose. He’s not really afraid, he insists, only irritated by all these inconveniences. A horror would surely have to be pretty tenacious to get under his skin—or at least to get him to admit it.

In fact, Gordon is basically an anti-Lovecraft—someone with no instinct whatsoever to move toward the scary thing, who finds creaky old houses more drafty than dramatic, and who’s delighted to return to the city with its “smells of smoke, cooking, and unhygienic humanity.” Perhaps this is some deep protective instinct, keeping him out of the way of the mysterious, romantic horrors that have done in most of his family. Until now, of course. Until the practical duty of selling an inheritance requires him to spend a day or two amid the rural creakiness.

Because despite the vast differences of personality, “Martyce” is not all that far from “Martense.” And family curses make little allowance for personality. Our insistently dull, endlessly whiny narrator, with his complete lack of patience for imaginative foibles, need only come briefly into contact with that curse for it to follow him home.

And once it gets going, it becomes clear that it truly is a ghastly curse. I love the turnabout idea of the camera that captures not your own soul that you wanted to keep, but the soul of something else that you’d rather have left behind. Something that can’t be seen by ordinary mean, but that can be made all-too-visible by just the right combination of device and treatment.

And Gordon—dull, practical, unromantic Gordon—is far too practical to risk passing that thing on to another generation, or to bring someone new into the family it’s attached to. I just hope Lucy—who probably deserved someone less whiny and patronizing than her not-quite-fiancée—is left immune thanks to her not-quite-affianced status, and able to move on.

Loving the city can be an invitation to terrible forces as well as protection—or both at the same time. Join us next week for N. K. Jemisin’s “The City Born Great.”

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.