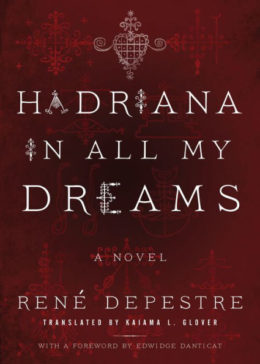

Hadriana in All My Dreams by René Depestre is considered one of the major works of 20th century Haitian literature—when I picked up the new English translation by Kaiama L. Glover, however, I wasn’t aware that I would also be able to include it in my QUILTBAG+ SFF Classics column. Yet the title character, Hadriana, displays attraction to people regardless of gender, and at a key point in the novel, she describes her sexual awakening with another young woman. This wasn’t the book I had been planning on reviewing this week, but I was very happy that it fit into the column.

I did know going in that Hadriana in All My Dreams would have speculative relevance: The book is an extended subversion of Western zombie stories, which freely appropriate Haitian traditions. Here, we get a zombie tale, but it is not the zombie tale we are familiar with from Anglophone media. As Edwidge Danticat puts in her foreword, contextualizing the novel: “The fact that we continue to be bombarded with the same old pedestrian zombie narratives written by foreigners and featuring Haitians makes this novel even more crucial” (p. 16).

Hadriana is a white French girl whose family lives in the seaside Haitian town of Jacmel—a real place, and also the author’s hometown. She is preparing to marry the young Haitian man Hector Danoze, who, besides his many other virtues, is also a trained pilot. Yet Hadriana gets caught in a web of magical intrigue, and as a result, passes away in the middle of her own wedding—just a few chapters into the book. The celebration takes on a funerary tone, and all the town’s secrets come to the fore in a masquerade (one that even features historical figures from Bolivar to Stalin). When Hadriana’s dead body vanishes, the entire town assumes she was turned into a zombie. But the protagonist—a child during Hadriana’s wedding who then grows up to become a writer and academic—eventually finds out more about the truth than he’d ever thought possible.

Without digging too far into the plot details, the book is not only noteworthy for offering a wide range of readers a view of zombies that’s rooted in the zombies’ own land and culture of origin; it also provides the undead with a voice. The audience is just as much the foreigner as the local reader—Depestre has lived in many countries since he became a political exile from Haiti. He wrote Hadriana in All My Dreams in France, where it was first published. It is very much a novel of exile, of diasporic longing toward the homeland of youth; and it doesn’t pull any punches. The political aspects might be less apparent to an American audience, though the glossary at the end of the book explains some of the more overt barbs, like the “Homo Papadocus” which satirizes the militia of Haitian dictator François Duvalier, also known as Papa Doc. But the other controversial aspect of the book—the unbridled eroticism and sexual violence—will make it across regardless of context and references to specific political situations.

Hadriana in All My Dreams is a very sexual novel, and it wears its sexuality on its sleeve. Even before we get to Hadriana’s encounter with death, we find out about one of the terrifying magical creatures of the town: a hypersexual young man who has been turned into a butterfly by a rival magician, and has become a kind of incubus assaulting women in their sleep. Nocturnal demons appear throughout the folklore of the world, so readers will probably be able to connect this creature to their own more familiar cultural traditions. Sex and violence intertwine freely here with chilling effect, and this initial story sets the tone for the entire book. The demonological folklore also meets the sexual folklore: One of the targets of the butterfly is a woman who has seven sets of genitals spread across her body, according to the town gossip.

Other reviewers are probably better-suited to discussing how this Francophone novel relates to Latin American magical realism. One of the motivators is the same for both, however (and is also characteristic of 20th century literary traditions in my own region, Eastern Europe)—namely, how the bizarre political situation in Haiti together with the traumatic encounter with subjugation ultimately contribute to an atmosphere where anything is possible.

Buy the Book

Hadriana in All My Dreams

The story plays with voice quite a bit, ranging from the folktale to the magazine article to the academic social justice jargon of the 1980s, and all registers are often presented with some amount of ironic distance. This distancing also helps the narrative to grapple with difficult topics. Hadriana as an attractive, mysterious young woman who met a grim end is fetishized by many. Yet she gains a voice of her own over the course of the novel, and we’re able to revisit some of the scenes that are initially described from an external viewpoint through her own perspective later in the book, as well. We also see her very painfully abandoned by her fellow townspeople, and their fear is driven by an overt political component in addition to the metaphorical. She is brave, self-determined, and queer to an extent that it is self-explanatory, requiring no labels—and while she is a white French woman, in this she is similar to the inhabitants of Jacmel. There is a fluidity of gender and sexual expression in both the wedding and funeral proceedings that the Church is desperately seeking to suppress; and even as Hadriana speaks of her same-sex sexual experience as a “sin,” she also speaks of it as such with defiant pride, flinging her words into the face of a priest (p. 209).

Hadriana is objectified to the extent of being read as a corpse, but the book pushes back against this conceptualization, and pushes back hard. To me, this is a major part of where its appeal lies. And it is a delicate balancing act: The novel tackles misogyny, and does so sometimes very bluntly, but neither the narrator nor the author condones the marginalization of women. (It’s sad that I have to state this, but I do feel that there are books which approach the topic much less successfully.) Even though the novel is quite short, it discusses an impressive range of subjects, from colonialism to academic environments to gender, and as well as their intersections; for example, Hadriana talks about how her whiteness in the Caribbean has benefited her as a migrant. The new translation conveys these subtleties with grace.

Depictions of the carnivalesque generally have an edge of social criticism (if this were an academic essay, I’d cite Bakhtin here…). So it is with this book: It can be read both as a vividly depicted story of magic and zombies, and as compelling social commentary. It’s a book that’s bursting at the seams with detail—don’t be surprised if something jumps out at you from among the pages.

Next time, we’ll take a look at another recently translated novel from a very different part of the world!

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is currently a finalist for the Hugo, Lambda and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.