This May, we’ll say goodbye to Game of Thrones. After eight seasons, one of fantasy fiction’s mightiest juggernauts will air a finale that’s sure to provide audiences with plenty of intrigue, a cracking script, some unforgettable visuals, and a disturbingly high body count.

And then what?

Well, there are certainly other compelling fantasy television series being made, and still others gearing up to go into production. But as great as shows like Stranger Things and The Good Place are, nothing has yet equaled Game of Thrones in its epic scale and ambition. Even with a new prequel series scheduled to begin shooting this spring, GoT is going to leave a massive hole in pop culture when it goes.

Fortunately for all of us, there’s another story waiting in the wings, perfectly positioned to fill that void. Enter Tad Williams’s fantasy novel trilogy, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn.

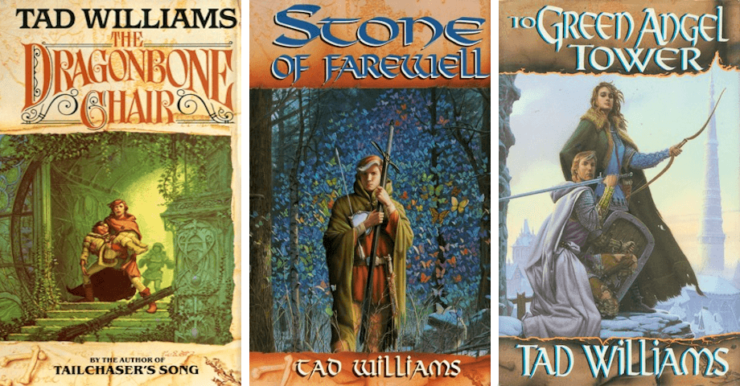

In case you’re not familiar with the series, Williams’s epic is comprised of three books: The Dragonbone Chair (1988), Stone of Farewell (1990), and To Green Angel Tower (1993)—the final installment is sometimes published as two volumes, due to its length. And, more than 25 years after the publication of that final installment , it’s high time we saw it lovingly translated to TV.

Three Swords Must Come Again

The plot follows Simon, a scullion in a sprawling castle complex built atop the ruins of a much older fortress. Initially content to moon about avoiding his chores, Simon sees his world upended by the death of High King Prester John (and no, this is not the last semi-obscure historical reference Williams will make in the series—not by a long shot).

Simon’s loyalty to the court wizard Morgenes—who insists on teaching him to read and write instead of how to cast magic spells—drives him beyond the castle’s walls into the wider world, whereupon the story expands to include several other narrators scattered across the continent of Osten Ard. Before everything is over, Simon will face dragons, woo a princess, and search for the trio of magic swords—Minneyar (Memory), Jingizu (Sorrow), and Thorn—that give the series its title, and offer the only hope of casting evil out of the land.

At a cursory glance, this description of the story might look like the rankest of fill-in-the-blank fantasy clones, right down to the plot coupons. Yet Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn is so much deeper than its summary suggests. Williams renders the world of Osten Ard with a sweeping, seamless intimacy, to a degree that sometimes while reading I’m able to close my eyes and imagine wandering its realms beyond the pages. It’s not only a grand world, but a mournful one: every place we encounter, from the swampy Wran to frozen Yiqanuc, seems to be grieving someone or something. The trilogy’s version of elves, the Sithi, are rendered unique and memorable by their grave sadness and their internal rift over whether to leave the world to mortals (to say nothing of how Williams keeps dropping hints that they arrived on spaceships). Throughout the quest for the swords and our journey through Osten Ard’s bloody history, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn interrogates notions of kingship, knightly valor, heroism, and destiny that lesser fantasy narratives often take for granted.

Buy the Book

The Dragonbone Chair

It’s very, very good, in other words. But so are lots of books and series. Why, you’d be right to ask, am I anointing Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn as the perfect television successor to Game of Thrones?

First of all, because it directly inspired Game of Thrones’s source material, A Song of Ice and Fire. In 2011, George R.R. Martin recalled:

The Dragonbone Chair and the rest of (Williams’s) famous four-book trilogy…inspired me to write my own seven-book trilogy. Fantasy got a bad rep for being formulaic and ritual. And I read The Dragonbone Chair and said, ‘My God, they can do something with this form…’

Let’s review: Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn is about a feud between claimants to an unusual throne—a feud that distracts everyone from a greater supernatural threat. This threat originates in the far north and is associated with inclement weather. A character of uncertain parentage comes of age through adventures in that same far north. One character is unusually short and has a penchant for dry remarks. Another has a metal hand. There’s a tame wolf, a sword named Needle, a character who starts out in a vast grassland distant from the rest of the cast, a character called “The Red Priest”…

To be clear, I’m not trying to accuse Martin of plagiarism by pointing out how familiar all this sounds. Anybody who’s read both “trilogies” knows they’re very distinct entities, and Martin’s imagination can’t be faulted. I’m only saying that he wears his influences proudly on his sleeve.

At the same time, a TV version of Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn (preferably with at least as big of a budget as HBO has given to GoT) wouldn’t just be three or four more seasons of Game of Thrones where everyone is suddenly calling Jon Snow “Simon” for some reason. The key difference is the tone—and it’s this difference that makes me believe the moment has never been more right to adapt Tad Williams’s opus.

If Early Shall Resist Too Late

It’s easy to look back at 2011, the year that Game of Thrones first premiered on HBO, as a less tumultuous time than the last few years have been, but of course the deepening political, social, and class divisions that have led to us to the current moment were already beginning to take hold. In the U.S., the 2010 elections had shifted the balance of power in the country toward the far-right of the political spectrum. The recovery from the Great Recession hadn’t benefited all of us equally. Many of us could hardly remember a time when America wasn’t at war.

People were, understandably, feeling a little bit cynical.

Into this environment exploded a gorgeous-looking, impeccably-acted, Emmy-hoarding event drama that brutally savaged the notion that there was anything noble in leadership and political control. The primary function of politics, said Game of Thrones, was not to benefit the people but to keep the most corrupt people in charge of as much as possible, and anybody who tried to change the system would be lucky to find themselves only beheaded. It’s no coincidence that the similarly-themed U.S. version of House of Cards became a hit around the same time.

And as the threat posed by the series’ real danger grew and developed across the seasons…well, pick your symbolism for the White Walkers. Mine is climate change. Others might see them as metaphorical representations of crumbling infrastructure, wealth inequality, inadequate healthcare, speculation that’ll cause the next recession, rampant gun violence, lingering racism, police brutality—a smorgasbord of issues that will continue to get worse while those with the power to address them look elsewhere. Oh, we might recognize the odd Jon Snow type desperately trying to tell us where the real fight is, but most of the time, watching the Starks and Lannisters and other aristocrats squabble while things get ever worse felt like looking in the mirror.

In many ways, the major political events of the last few years have appeared to validate all the cynicism that helped propel Game of Thrones into the zeitgeist. There have certainly been stretches of time in the last couple of years in which every day seemed to sketch a new low for kindness and decency. But then a funny thing happened. People who once thought that nothing could be done to change the system began to rise to the occasion.

Since the last presidential election, more Americans now know the names of their elected representatives than at any time in living memory. Protests, from #MeToo and the Women’s March to Extinction Rebellion, are now institutions rather than aberrations, and a surge of passionate activism and engagement led to the election of the most diverse Congress in American history just last year. While some took the International Panel on Climate Change’s dire late-year report as a reason to give up all hope, others took it as a moonshot challenge.

The mood is energized. In the last year or so I’ve noticed people from all walks of life saying ‘enough is enough’ and deciding to work for change.

So why am I here, talking about television?

To Turn the Stride of Treading Fate

One of the purposes of fantasy is to reflect the real world in such a way that we look on it with new eyes, and from a fresh perspective. As the mood of the era turns toward a fight for justice, Game of Thrones‘s reflections are beginning to look dated. Daenerys, Jaime, Tyrion and the rest look a little awkward trying to pivot from struggling and grasping after power to fighting for the greater good. There’s a reason Season 7 sometimes felt like a different genre from the rest of the show: it just hasn’t convincingly laid the groundwork for kindness and empathy.

Not so with Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. Tad Williams isn’t writing about amoral rulers and mercenaries fighting over the scraps of a fallen world. Rather, his characters are fundamentally good people who feel outmatched by the scale of the threats arrayed against them.

Simon, Miriamele, Binabik, Josua, Maegwin and those who join them are not looking to spin the evils of the Storm King to their own advantage—they’re merely trying to cling to whatever flimsy hopes they can find. They spend most of their time trying to claw their way back to zero while suffering setback after setback. At times, even the least of their enemies seems insurmountable.

Raise your hand if you had a day during 2018 when just being alive felt like that. (I know mine’s in the air.)

By focusing on the scale of the threat rather than the moral inadequacy of the fighters, Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn pulls off the delicate balancing act of being both bleak and hopeful. It’s best described as “hopepunk,” the recently-coined term for grim fiction which nevertheless embraces the idea that hope is never misplaced.

In between testing the limits of how much he can make his characters suffer without killing them, Williams takes care to note the things that make the fight worthwhile: quiet moments stolen with friends, songs on summer days, the birth of a child who might at least be expected to have different problems than the ones you have, the pleasure of witnessing beautiful things, baking bread, the simple ferocity of being still alive among the ruins. Just as Josua and his allies don’t know what the three swords will do once they’ve finally been gathered, so too is the end of the fight obscured from us—but that’s no excuse to stop fighting.

Beware the False Messenger

Another reason Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn makes the perfect balm for our times is its celebration of intellectuals. Early on, the only people who realize the true nature of the actual threat to their world are a scattered group of scholars known as the League of the Scroll, who correspond over long distances to share ancient wisdom. Their membership knows no national boundaries, and has no entry requirements beyond being chosen by another Scrollbearer. As the story races on, they prove a considerable obstacle to the villains’ plans, simply because they read books and share knowledge.

In an age when anti-intellectualism seems steadily on the rise, with a sizable portion of the population arguing that college and university educations have a negative impact on the U.S., this is a resonant message.

The series’ multiculturalism is also an important feature: Osten Ard is a land of many nations, from the pagan Hernystiri to the cosmopolitan Nabbanai—and that’s only the humans. Each of these nations is represented in the story by several named characters, all of whom run the gamut from good to irredeemable. Seeing northern warleader Isgrimnur, seaside princess Miriamele, imperial knight Camaris, and rural southerner Tiamak work together for the good of all will strike an encouraging note for anybody worn out by the relentless drumbeat of othering playing out in real life.

There are no orcs in Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn, no inherently villainous races. The closest thing are the Norns…but once you realize they’re basically dispossessed aborigines, the entire picture shifts.

Finally, everyone should want to see Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn on screen because it would look so damn cool. One of the many strengths the Osten Ard universe shares with A Song of Ice and Fire is a vivid visual language, and I’ll forever lament the dearth of decent fan art for Williams’ series. There’s so much to draw: the Gossamer Towers of the lost Sithi city of Da’ai Chikiza, the frozen waterfall of the Uduntree, the vast empty hallways of Asu’a, the floating swamp city of Kwanitupul…like I said, it’s a place you can dream of wandering and getting lost in.

Now, it should be said that the trilogy could use some updating in certain respects. Sexual orientations other than straight are never more than faintly implied, and the character descriptions tend to be pretty Nordic overall, with Tiamak and Binabik perhaps the only exceptions. Furthermore, Miriamele’s internal conflict over not being able to love Simon because of her rape by a previous partner would probably be handled differently in 2019. But none of these are insurmountable obstacles. With whatever relatively minor changes are necessary, I’d argue that television creators would be fools not to adapt Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn. And until the powers that be heed my warning, every fantasy fan—and every reader who could use a more hopeful, positive perspective and way of understanding the world—should read it.

Earlier, I said that fantasy has the power to reflect our view of reality so that we see the world in a new light—it can also inspire and intensify our ideas and emotions. Our current world, with its inspiring mix of striking teachers, green rebels, outspoken teen activists, and a new generation of young people running and winning public office, deserves a fantasy that’s as raw, hopeful, and indomitable as the people who are fighting to make it better. So, really…what’s HBO waiting for?

Samuel Chapman is a writer who lives in Portland, Oregon with his girlfriend, a lot of smoked fish, and a perpetual drizzle. His short fiction has appeared in Metaphorosis, Buckshot, and Third Flatiron’s Terra! Tara! Terror! anthology, and more of his thoughts can be found on his blog, “To Find the Colors Again.” He also writes The Glass Thief, the world’s greatest crustacean epic web serial, and tweets Christmas crossover crises and unsolicited Sly Cooper quotes @SamuelChapman93.