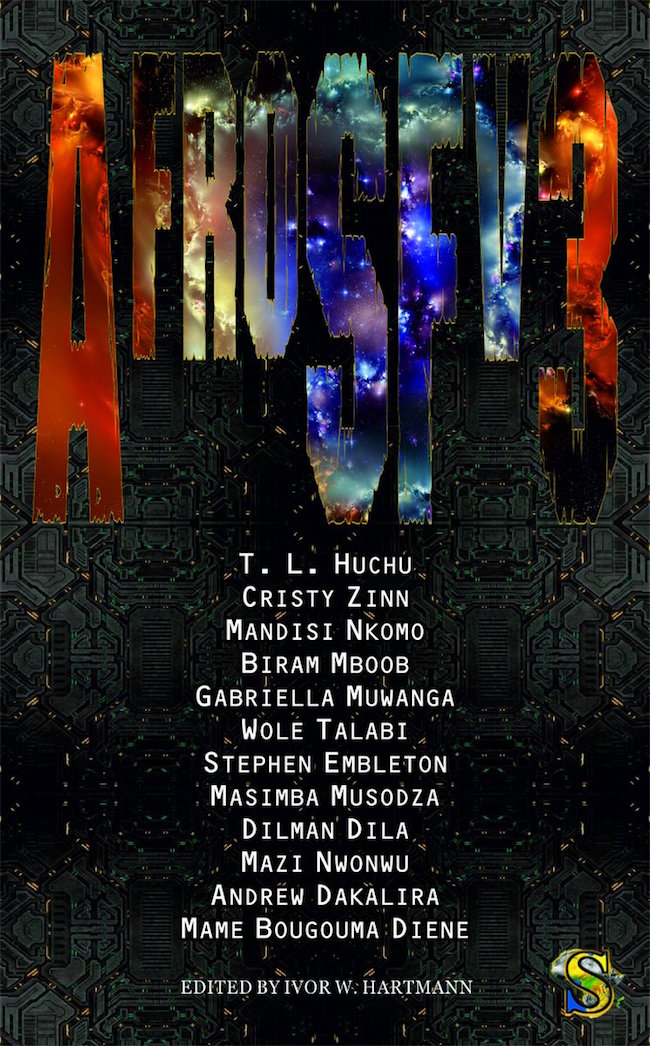

AfroSF Volume 3 is—exactly as the title would indicate—the third volume in a series of original fiction by contemporary African writers. The first two volumes, published in 2012 and 2015, featured authors that have now become household names for genre readers, including Nnedi Okorafor, Sarah Lotz, and Tade Thompson. The third volume, with a dozen stories commissioned by Ivor Hartmann, continues the series’ commitment to introducing contemporary African writers to readers around the world.

The theme, loosely, is space. As Hartmann notes in his introduction: “We are ineffably drawn to it, and equally terrified by it. We have created endless mythologies, sciences, and even religions, in the quest to understand it.” It is, Hartmann says succinctly, an “astronomical wilderness.”

If the latter evokes Roddenberry’s famous words, that is only fitting. From the opening paragraphs of the first story—T.L. Huchu’s “Njuzu”—we’re straight into a joyously televisual SF future, complete with “transparent panelling,” “carbon fibre walls,” and the occasional “hologram.” The trend continues throughout AfroSFv3, as writers revisit all the iconic and delightful staples of aspirational science fiction: interstellar empires, FTL networks, ansible and asteroid mining, AIs and alien contact, virtual worlds and power armor. From space opera to high-flying hard SF, AfroSFv3 covers all the bases.

But AfroSFv3’s writers bring new talent—and new perspectives—to the familiar. In “Njuzu,” for example, Huchu interweaves traditionally SF vocabulary with Shona mythology to create a literary fusion that’s distinctly un-Trekky. Half hard-science, half-mystical, this is Golden Age SF at its best—while also taking a perspective that Golden Age SF never even conceived. And brilliantly written: “Njuzu” rises about the cold facts of science to describe a transcendental, if mournful, vision of humanity’s future.

Mame Bougouma Diene’s “Ogotemmeli’s Song” is a similarly creative mix of mythology and hard science, with two space empires competing for the ownership—and soul—of the universe. Vast in scale, it doesn’t shy away from cosmic conflict, with planetary elementals battling corporation starships. Andrew Dakalira’s “Inhabitable” has similar themes—and scale—a hard SF story of crisis across civilisations and cultures, while focusing on the stresses and sacrifices of the individuals at its centre.

Cristy Zinn’s “The Girl Who Stared at Mars” has an equally vast scale, but takes a more intimate approach. With Earth in tatters, the best people are being flung at Mars, one small ship at a time. As our protagonist gets closer and closer to her new home, the simulation—the ship’s holodeck, designed to keep her occupied and sane—becomes distressingly insightful. The story’s focus on a single, isolated, entirely internalised drama is a bold move (given the apocalyptic backdrop) but better—and more tense—for it.

“The Far Side,” by Gabriella Muwanga, is perhaps the most traditionally “classic” tale, featuring innovative science, some derring-do, a race against the clock, and a heroic space captain. But here too the author takes an intimate, not epic, approach. Mason’s asthmatic daughter has been forbidden the Moon. But the ruined Earth is no place for her either, so Mason has to run a terrible risk: smuggle his five-year-old daughter into space, and all the way to the Moon, and hope not only that she survives, but that they don’t get caught in the effort. Masimba Musodza’s “The Interplanetary Water Company” is also good clean fun: plucky protagonists set off to recover lost super-tech from an inhospitable planet. The pay-off hints towards future adventures as well, with noble scientists competing against a greedy galactic empire.

Dilman Dila’s “Safari Nyota: A Prologue” is tantalising, if upsettingly unresolved. The first part of an ongoing multi-media project, it sets up the the greater narrative’s first major conflict. A ship on course to a distant planet is knocked off course, leaving—of all things—a droid to make the critical decision on how (or if) to save its sleeping crew.

For fans of space opera, Wole Talabi’s “Drift-Flux” is wall-to-wall action, as one could expect with a story that starts with an explosion (and an homage to Alien). Orshio and Lien-Adel arrive outside Ceres Station, just in time to witness—and be blamed for—the destruction of a mining ship. In rapid-fire sequence, they’re up to their necks in mayhem, as the pair find themselves entangled in an apocalyptic plot. “The EMO Hunter” by Mandisi Nkomo is equally fast-moving, a svelte combination of Blade Runner and domestic thriller. The latter makes for an intriguing contrast with Stephen Embleton’s “Journal of a DNA Pirate,” which also tackles repressive government and genetically-fuelled self-doubt, albeit from the perspective of a revolutionary’s diaries.

Buy the Book

AfroSFv3

Mazi Nwonwu’s “Parental Control” is one of the anthology’s high points. Dadzie is unique—the child of an android mother. He hides from the awkwardness of reality in a never-ending cycle of virtual games. He’s forced to face reality (literally and figuratively) when he joins his father’s home. Although the virtual sequences are joyously bonkers, the story’s finest moments occur around the kitchen table, in terse conversations between Dadzie, his father, and his step-mother.

And, last, but not least, my personal favourite. Biram Mboob’s “The Luminal Frontier” is an absolutely soaring story that interweaves all-powerful AIs, a tiny bit of time travel, and interstellar trade routes. If slightly chillier than some of AfroSFv3’s more personal tales, it makes up for that in sheer ambition. “Luminal” is set—in a thematically significant way—at the changing of the civilisational guard; a cosmic butterfly effect pin-pointed on a single moment of painfully human choice.

The language is particularly sublime, as Mboob describes the impossible in deeply evocative terms: focusing less on the scientific underpinning and more on the characters’ emotional response. “The Luminal is our eternal and infinite cathedral,” he writes—a distinctly non-prosaic description of an FTL network. This is all the science and imagination and potential that makes for good science fiction, wrapped in the humanity and emotion that makes it great.

With an anthology like AfroSFv3, there’s the well-intended—but ultimately slightly patronising—framing of “discovery” (made all the easier for the strained Roddenberry metaphor). But “discovery” implies an element of challenge; a hint that these stories might be a bit too far out on the edge, or potentially unpalatable. Nothing could be further from the truth. Hartmann’s space-themed anthology taps into the vein of SF that we already know and love: celebrating the universe’s grandeur and possibility.

AfroSFv3 is available from StoryTime.

Jared Shurin is the editor of The Djinn Falls in Love, The Outcast Hours, The Best of British Fantasy, and many other published and/or forthcoming works. He writes irregularly at raptorvelocity.com and continuously at @straycarnivore.