I grew up on a healthy diet of the usual suspects, in terms of fantasy authors—J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and J.K. Rowling. But my personal favorite during my adolescent years was David Eddings. His books were the ones that truly snared me, showed me the rules and tropes of the fantasy genre, wedging that hook deep in my brain and reeling me in—the books that were unputdownable.

I went on my first quest through the eyes of Garion, learned about magic, the Will and the Word, and discovered the battle that raged behind the scenes between good and evil. For my pubescent self, this battle made sense; it felt right. In reality, I was finding out the world could be hard and mean, and even oppressive, and the idea of pushing back against those forces—of taking a stand against the bullies, against the red-cloaked grolims of the world—felt righteous.

In the fictional world I inhabited, Eddings made it so damn easy to differentiate just who it was I was fighting against. For young me, this made the journey more enjoyable. The black and white characters meant that I didn’t have to waste time figuring out who was right and who was wrong, and could focus instead on the virtuousness of the battle at hand. Eddings did everything to serve it up to me—the band of heroes I traveled with were honorable and amicable. They bantered, for god’s sake! Oh, they had flaws, but Silk’s thievery, Barak’s propensity for violence, Ce’Nedra’s conceitedness, and Mandorallen’s thick-headed nobility were laughed off and eye-rolled into harmlessness like a classic Eighties sitcom. These were the good guys.

The villains of the piece may as well have been filled in with a paint-by-numbers set: the evil priesthood wore robes the color of old blood, they sacrificed people on altars, and were led by a scarred and narcissistic god. There were no shades of grey here; these were the bad guys.

This clear division of good versus evil meant that I knew where I stood, knew who to root for and who to revile. It clarified my world and gave me a code to follow. It helped confirm the knowledge that I was one of the good guys.

But that code started to fail as I got older. Back in reality, as I left my teenage years behind, I discovered that the world just wasn’t that clear cut. Wading into my university years, I met people who by all rights should have fallen into the darker side of that black and white division. They did things heroes weren’t supposed to do like smoked, drank, and took drugs. Some of these people cheated in their relationships, they lied, they made mistakes. But the thing was, I liked these people. In some cases, I even looked up to these people.

And then I was tempted, like all heroes eventually are, and I did some of those things heroes aren’t meant to do. My clear-cut perception on good and bad fractured, and I, like all people learning to become an adult, was lost trying to decide if I was a hero or a villain.

As shades of grey entered my real world, my fantasy worlds started to suffer for it. I continued to digest authors of similar ilk to Eddings—David Gemmell, Raymond E. Feist, and Robert Jordan—those writers who adhered to the familiar rules of fantasy. In their universes there was always a dark lord, or dark army, to pit oneself against. It was pretty clear—the heroes usually just needed to attack the evil-looking creatures of the night attempting to kill the innocent villages in order to win the day.

But this no longer squared with what I was exposed to in the real world. Those identifiable attributes that marked someone as Good or Evil simply didn’t hold up. No one could live up to the title of hero—so that either meant there were no heroes, or it was far more complicated than I’d been led to believe.

Because of this I started to get fantasy fatigue. Books had always been my mirror to the world and a way of figuring things out, but what I was reading just wasn’t offering the guidance it used to. I started reading outside the genre, leaving fantasy behind, for the most part.

Until Martin. George R.R. Martin had written the first four books of his A Song of Ice and Fire series when I eventually set about reading them. This was still years before HBO’s adaptation took the world by storm. I remember attempting A Game of Thrones when I was still in high school, but the dense text, the imposing horde of characters, and the complex worldbuilding was above me at the time, and after a few chapters I set it aside in favor of the more accessible Eddings.

But eventually a friend told me I should really read it. And the blogs and fantasy websites told me I should read it. So I bowed to peer pressure and returned to the fantasy realm.

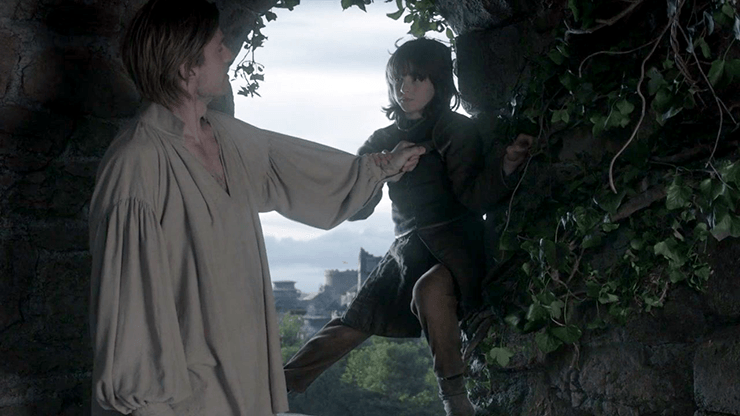

At the start, I thought I knew exactly what I was in for. The initial set-up made it clear who our protagonists were—the House of Stark—and introduced our antagonists, the House of Lannister. Jamie Lannister pushed an innocent kid out of a tower after having sex with his own sister, for crying out loud! It doesn’t get much clearer than that.

Buy the Book

The Ruin of Kings

And then I kept reading…and before I knew it, I didn’t know where I was, or what was going on. Characters that appeared irredeemable redeemed themselves, and even became downright likable. Characters I thought of as good and noble made bad decisions and suffered for it. The whole thing fractured in ways I never saw coming, Daenerys the thirteen-year-old ended up falling in love with the savage horse lord who all but raped her (or arguably did rape her) on their wedding night; then the horse lord turned out to be more honorable than Daenerys’ own brother, and then the horse lord dies!

Every time I thought I had regained my bearings, categorized every character into the good or bad list, they would make decisions that set it all on fire and I had to start again. Characters that shouldn’t die (at least according to the rules I’d internalized) met with horrible ends, and characters that deserved to die flourished. By the time I found myself empathizing with Jamie Lannister, even rooting for him—the same guy who books earlier had indulged in incest and then the casual attempted murder of a child, I stopped trying to make sense of it. And felt better for it.

Once again my fantasy world mirrored my real world, at least in some ways, and because of that I could learn from it. All the complexities of the human condition, all the infinite shades of grey, were there; and from this shifting maze I learnt much more about the subtleties and nuances of what it means to be good and what it means to be evil.

Fantasy has always helped me understand the world, from the metaphors it employs, to the parallels with our own world, to the thoughtful exploration of its themes—one of the most important being the struggle between good and evil. As a reader, I am thankful to the clear-cut worlds of David Eddings for taking my hand and showing me the outlines of these concepts, and introducing me to characters that made the journey a joy. And I’m thankful, too, to the worlds of George R.R. Martin for helping me understand the profound depths and messiness of the same concepts, and that being a hero or a villain is never that straightforward—a realization that’s surprisingly reassuring, in the end.

Jonathan Robb is an Australian lost in London who spends his spare time reading and writing, and looking for entries into Narnia. You can find more of his work at his website.