At the entrance to the town they put on visibility. It made them no warmer, and impaired their self-esteem.

In the last decade of her life, author Sylvia Townsend Warner (1893-1978) told an interviewer that “I want to write about something different.”

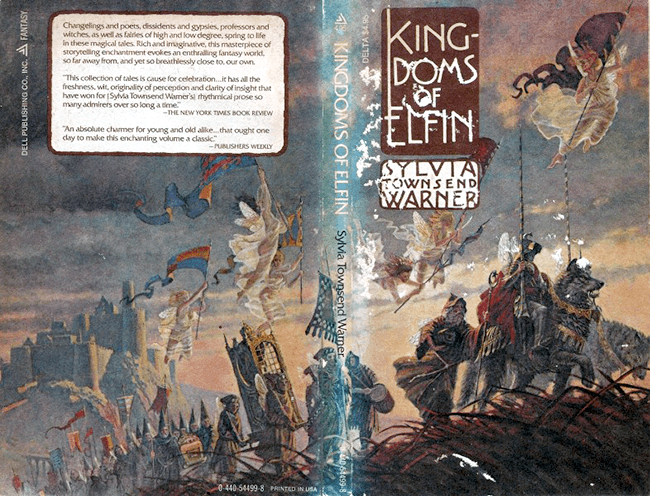

That different turned out to be fairy tales. Warner had played with themes of magic and enchantment in her work before, and always had an interest in folklore, but for this project, she tried something a bit different: interconnected stories of other and fairy. Most were published in The New Yorker from 1972-1975, and collected in the last book printed in Warner’s lifetime: Kingdoms of Elfin (1976). Regrettably out of print for decades, the collection is now being reissued by Handheld Press, with a foreward by Greer Gilman, an introduction by Ingrid Hotz-Davies, and extensive footnotes by Kate Macdonald.

Warner came from a comfortable, well-educated family. Her father, George Townsend Warner, a history teacher at Harrow School, took over his daughter’s instruction, and allowed her full access to his extensive personal library. The result was an interest in history that Warner never lost, and which comes through in many of her works—including Kingdoms of Elfin. In 1917, she began her own career working as a researcher of music for the ten volume Tudor Church Music, work that allowed her to call herself a musicologist for the rest of her life. She also wrote poetry, fiction and biography, including a biography of T.H. White.

Despite this distinguished literary and research career, she arguably became best known for her personal life as one of London’s Bright Young Things. In the 1920s, she (like many others in her social group) scandalized many when she started a passionate relationship with a married man. Those scandals grew when, in 1930, she continued with a fierce relationship with poet Valentine Ackland (1906-1969) whose life and work explored issues of gender. Ackland, born Mary Kathleen Macrory Ackland, called herself a woman and used the pronouns “she” and “her,” but changed her name to something less obviously gendered, and usually wore male clothing. It’s possible that had Ackland been born a hundred or even fifty years later, she would have identified as non-binary or trans, and happily embraced the singular pronouns “they” and “them.”

Alarmed by the rise of fascism, the two joined the Communist Party and remained politically active throughout World War II. After the war, Ackland began drinking heavily and sleeping with other women, but stayed with Warner until Ackland’s death from breast cancer. Warner never lived with another woman again.

The stories in Kingdoms of Elfin were written after Ackland’s death. An interconnected series of tales, they can be read as standalones, or as a group. Later tales often reference characters or places from previous tales, but never assume that readers have read the previous stories—possibly because most were originally published in The New Yorker, where Warner and her editors could not be sure that readers would have seen, much less read, previous issues.

I cannot say just how much of Warner’s life is reflected in these tales. I can, however, say that the stories often sound exactly like the sort you might expect from a trained historian and scholar. They are littered with references to various historians, ancient, modern, real and imaginary, along with frequent acknowledgements that these historical accounts have often been disputed, as well as an occasional discussion about a historical point or other, or an offhand observation that a “true” British name has been lost beneath a Latinized form, or a reference to Katherine Howard’s ghost as a quite real thing.

This sort of approach not only helps to create an impression that Warner’s imaginary kingdoms are, indeed, quite real, but also gives Warner the chance to poke fun at her fellow scholars—and also, from time to time, make a pointed comment about the very male and British gaze of those scholars. It works, too, as a way to use fairy tales as historiographic and scholarly critique.

But it’s not all historical stuff—Warner also slides in some teasing observations about poets (she was, after all, a poet herself)—glowing descriptions of (some) birds, and rich descriptions of food. I don’t know if she cooked, but I can say she enjoyed eating. And interestingly, despite all of this history, and an almost offhanded insistence that Katherine Howard’s ghost is quite, quite real, many of the stories are not rooted in any specific time—one tale does partly take place in a very firm 1893, in Wales, but that is the exception, not the rule.

But if they are not rooted in any specific period, her tales are rooted to very specific places, and very deeply in folklore and fairy tale. Specifically and particularly British folklore and fairy tale, but Warner does occasionally leave the British Isles to study a few European countries and the Middle East. Familiar characters such as Morgan le Fay, the Red Queen from Alice in Wonderland and Baba Yaga get passing mentions; a few characters, like Thomas the Rhymer, receive a bit more attention. Most of her characters are fairies, humans, or changelings—that is, human children stolen away by fairies, and the fairy children left in their places to try to make their way in the human world. But the occasional Peri slips in, along with Hecate and one rather scandalous ghost.

That rooting in folklore and fairy tale, along with the frequent references to specific fairy tale traditions and histories, means that her tales feel less like an attempt to create a new mythos or history of fairies, much less a new secondary world (in contrast to, say, her equally erudite fellow Brit J.R.R. Tolkien), but more an attempt to correct previous histories. She spends considerable time explaining, for instance, that the common belief that fairies are immortal is quite wrong: they are long lived, but they can certainly die. And in these stories, often do. She also quibbles with other details of fairy customs as related by human scholars.

But as described, her fairies also sound as if they’ve stepped directly out of Victorian illustrations—her fairy queens, for instance, are usually beautiful, and slender, with long shimmering wings, which most of them never use. Warner also works with the common belief that fairies, unlike humans, have no souls. In her account, this soulless nature has consequences, largely beneficial ones from the fairy point of view: as soulless creatures, they do not believe in an afterlife, and therefore, do not worry about might happen to them after death. A few still end up in church buildings for one reason or another, and two—for reasons I won’t spoil—(sorta) end up running a couple of bishoprics in England, but in general they find themselves puzzled or indifferent to religious matters, something that allows Warner to play with ideas of atheism and to lightly mock religion, religious practitioners, atheists, and agnostics.

But very much like the way the fairies of the French salon tales frequently sounded and acted like French aristocrats, the inhabitants of Elfin often sound like they’ve stepped straight out of Downton Abbey. Including the ones who live in France. Including the ones that take place outside the actual kingdoms of Elfin, or just on its edges—the places where humans and fairies may end up interacting, not always for the best, as when a fairy ritual of moving a mountain around does some accidental damage to a mortal who was, understandably, not expecting the mountain to move at all. And including the ones where fairies wander from their homes—sometimes purposefully, sometimes by exile—and accidentally find themselves someplace else.

Buy the Book

Finding Baba Yaga: A Short Novel in Verse

I’ve made these tales, I fear, sound rather boring, like dry history or scholarly literature. And, to be fair, the stories here tend to be slow reads, the sort you read for the joy of the language, style, not the plot. Oh, yes, these stories do have plots—unpredictable plots at that, since the cold, soulless, often accidentally cruel fairies do not always act or speak in unexpected ways. As when a fairy is told that he must prostitute himself out to a human man to allow his four companions to survive, with the comfortable assurance that it is far easier to submit to a man than to a woman. (In the end, the fairy making that assurance is the one to stay with the man.) Unexpected since I couldn’t help feeling they had other options—but even fairies need food and drink. Or the way that, in “The Occupation,” a few humans do realize that they might—just might—have fairies in their midst. Or the fate of that mountain that keeps getting moved around.

That unexpectedness does, to repeat, include moments of brutality and cruelty—these are stories about soulless fairies, after all. So it’s not entirely surprising, for instance, that Elphenor and Weasel become lovers about thirty seconds after they first meet—and after she slaps his face and he pulls her down to the ground in response. And as Warner warns readers early on, fairies can die, often not gently. Several moments—as in a scene where a fairy child is pecked to death by seagulls—are pure horror.

Not all of the stories quite work as stories, alas—indeed, one only “ends” because, well, a new story starts on the next page, which is not really the best way to end a story. And as said, this collection can make for slow reading. But worthwhile, I think, for the sentences with odd, sharp beauty, like these:

Ludo had been blooded to poetry at his mother’s knee.

I think something similar could have been said of Sylvia Townsend Warner.

One word of warning: one story, “Castor and Pollux,” does have an anti-Semitic statement. In context, it’s meant as a reference to Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, but the use of the plural gives that reference a much broader and more chilling meaning. This same story also includes the death of a woman in childbirth, a death that in context rather uneasily reads as a punishment for sexual behavior, and a later attempt to murder children. Some readers may simply want to skip this tale.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.